I am your son,” the pharaoh says to the Egyptian sun god Re in an Old Kingdom pyramid text (c. 2300 B.C.).1 From an early period, Egyptian pharaohs were regarded as divine, the offspring of gods. Did this influence Hebrew understanding of kingship? And did it, either directly or indirectly, through Hebrew mediation, affect Christian understanding of Jesus of Nazareth as the son of God?

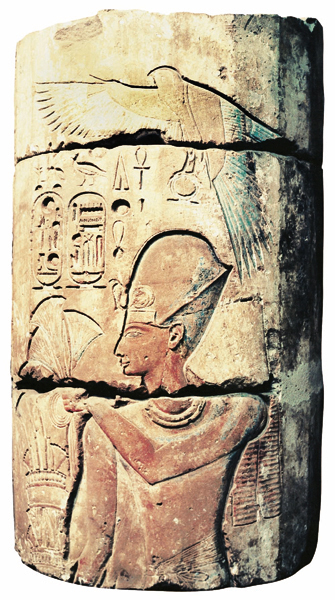

In almost every royal inscription from ancient Egypt, the pharaoh is called “the son of Re,” the sun god. Re was the preeminent deity in the Egyptian pantheon through most of the three millennia of pharaonic history.

Beginning in the early second millennium B.C., pharaohs had five names. The last, called the nomen, was the birth name. The second to last, called the prenomen, almost always contained the name of the sun god Re. These last two names were the only ones used in the oval figure, called the cartouche, that officially identified the king.

The prenomen (as well as some of the pharaoh’s other names) was given to the pharaoh at his coronation. Thus, he became the son of god at his coronation.

In Egyptian mythology, the deity Horus, pictured as a falcon or a falcon-headed man, is also the son of Re, and in Egyptian iconography the Horus falcon is closely identified with the pharaoh. The pharoah’s first name, known as the Horus name, always begins with the hieroglyph of the “Living Horus” (

Given to the pharaoh at his coronation, the divine sonship of the pharaoh is sometimes referred to as “adoption” sonship. The pharaoh’s heir was believed to become the incarnation of Horus, the son of Re, upon the death of his father.

In the famous Tale of Sinhue, the death of Pharaoh Amenemhet I (1963–1934 B.C.) is announced as follows: “The King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Sehetepibre [his nomen] flew to heaven and united with the sun-disc, the divine body merging with its maker.”3 Upon receiving news of his father’s death, the crown prince, Senusert, who had been campaigning in Libya, departed for the capital to take over the kingship: “Not a moment did he delay. The falcon flew with his attendants.”4 Senusert had become the Horus falcon, the “Living Horus.”

The divine nature of the Egyptian monarch is also reflected in other epithets. During the Old Kingdom (2700–2200 B.C.), the epithet “great god” (

In Israel, by contrast, the very idea of human kingship was problematic. The Hebrew Bible is replete with references to God, not man, as king. In his blessing on Israel before his death, Moses states, “Thus the Lord became king in Jeshurun [a poetic name for Israel] when the heads of the people were gathered, all the tribes of Israel together” (Deuteronomy 33:5). The judge Gideon refused the offer to be king on the grounds that “the Lord will rule over you” ( Judges 8:23). The psalmist declares,“The Lord is king forever” (Psalms 10:16), and the prophet Isaiah records God as saying, “I am the Lord, your Holy One, the Creator of Israel, your King” (Isaiah 43:15). When the people demanded a human king to meet the Philistine threat, Samuel at first resisted; he was “displeased” (1 Samuel 8:6). He foretold nothing but oppression under a human king: “You will cry out because of your king…but the people refused to listen” (1 Samuel 8:18–19). So Israel had a human king by the end of the 11th century B.C.

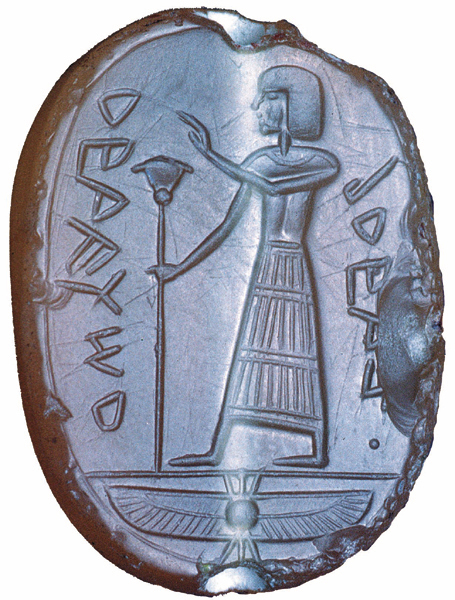

On the face of it, it seems unlikely that Egypt exerted a significant influence on Israel at this time; Egypt was in political decline in the 21st and 22nd Dynasties (c. 1069–715 B.C.). During the period of David and Solomon (tenth century B.C.), however, the most formative period for Israel’s monarchy, close ties existed between Tanis, the 21st Dynasty capital, and Jerusalem.7 The warmth between the two countries reached its zenith with the political marriage of Solomon to the daughter of a 21st Dynasty pharaoh who remains unnamed in the Bible, but who probably was Siamun.8 In addition, Egyptian royal iconography influenced the Levant centuries before Israel’s monarchy, in the form of statuary, stelae and glyptic art.9 Though Israel’s available official and royal iconography is limited, Egyptian influence is obvious. The human figure on the recently published seal of a high official in King Hoshea’s court (see Israelite seal) is clearly in Egyptian style, and the seal includes an Egyptian winged sun-disc.a This same winged sun-disc also appears over the figure on “Solomon’s” seal, just published in Biblical Archaeology Review.b These seals suggest that Israel looked to Egypt for inspiration regarding kingship. Israel’s fledgling monarchy had no royal archetypes of its own to draw on, and Egypt was its closest and most influential neighbor. It seems natural that Israel would appropriate language and motifs of kingship that were compatible with its monotheistic worldview.

The role of the king in Israel as described in the biblical text is similar to that of the Egyptian pharaohs. Like Egyptian kings, Israel’s kings served as the final arbiter in judicial matters (2 Samuel 14:4–20; 1 Kings 3:16–28; 2 Kings 6:26–29). Israel’s kings also had decisive military roles and fought with divinely inspired might and strength (cf. 2 Samuel 22:35 = Psalms 18:34). Like Egyptian kings, Israel’s kings had religious responsibilities—building and refurbishing temples and carrying out some priestly duties (2 Samuel 6–7; 1 Kings 8). However, there were distinct limits to the priestly functions Israelite kings could serve. When they exceeded these limits, they were divinely punished (cf. 1 Samuel 13:8–14; 2 Chronicles 26:16–21).

Most ancient Near Eastern kings had military, religious and judicial responsibilities. Thus these “parallels” between Egypt and Israel do not prove that the latter was influenced by the former. But there seem to be more than superficial similarities between Egypt’s and Israel’s idea of the king as the son of god.

Consider Israel’s use of royal names. Like their Egyptian counterparts, Israelite kings may have had both a birth name and, later, a throne name. King Solomon’s birth name was Jedediah and his throne name may have been Solomon. This is suggested by an intriguing passage in 2 Samuel 12:24–25: “[Bathsheba] bore a son, and [David] named him Solomon. The Lord loved him, and sent a message by the prophet Nathan; so he named him Jedediah, because of the Lord.” Similarly, a ninth-century B.C. Judahite king is called Uzziah in 2 Chronicles 26:1–23 and Azariah in 2 Kings 15:1–7 and 1 Chronicles 3:12.

More directly relevant are two passages in which a Hebrew king appears to have been regarded as a son of God. In 2 Samuel 7:14, Yahweh, the God of Israel, speaks to David regarding his heir: “I will be his father, and he shall be my son.” And in Psalm 2:6–7 the psalmist quotes Yahweh: “I have set my king on Zion, my holy hill…You are my son; today I have begotten you.” Both passages have been used to support the adoptionist view of kingship, whereby the king becomes the son of the deity upon his assumption of the throne.

Many scholars question whether the concepts embedded in these passages have any connection whatever with the Egyptian concept of divine kingship. The late Roland de Vaux, of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française, suggested that Psalm 2 contains an adoption formula similar to that found in the Code of Hammurabi.10 Other scholars argue that the terms “father” and “son” in various Semitic texts indicate the suzerain and vassal in a covenant/treaty relationship.11 Still others see a “fusion of adoption and covenant connotations” in Psalm 2.12 A number of recent commentators on 2 Samuel have endorsed this dual emphasis.13

The late Peter Craigie, an Ugaritic and Hebrew scholar, took another tack with respect to Psalm 2. Craigie saw something deeper happening at the king’s coronation than adoption by the deity: “‘I have begotten you’ is metaphorical language; it means more than simply adoption, which has legal overtones, and implies that a ‘new birth’ of a divine nature took place during the coronation.”14 Similarly, according to Henri Frankfort, the Dutch Orientalist from the University of Chicago, the pharaoh is transformed into the divine king during the coronation. As Egyptologist Lanny Bell put it:

[The king] actually becomes divine only when he becomes one with the royal ka, when his human form is overtaken by this immortal element, which flows through his whole being and dwells in it. This happens at the climax of the coronation ceremony, when he assumes his rightful place on the “Horus-throne of the living.”15

The coronation ceremony is the key in Egyptian and Israelite traditions, even if they have different theological bases. Keith Whitelam, of Stirling University (Scotland), proposes that the “sonship” of the Israelite king derives from the anointing ceremony, in which the spirit of God (rûah ’

This is quite different from the theology of Egyptian divine sonship where the convenantal concept is absent. But in both Egypt and Israel, the term “son” demonstrates a spiritual link between the deity and his earthly ruler, which is characterized as a unique father-son relationship. This doctrine legitimizes the king in the religio-political traditions of both nations.

The epithets “Son of Re” and “Living Horus” continued throughout pharaonic history. They were even applied to foreign rulers, such as the Cushite kings of the 25th Dynasty,17 Alexander the Great and his successors,18 and the Roman Caesars.19 This does not mean that the idea of the divine sonship of the king remained unaltered through the millennia. On the contrary, the mythological foundation of divine sonship, in the words of one scholar, “suffered a serious debasement” during the Second Intermediate Period (1786–1550 B.C.), from which it never fully recovered.20 But divine pharaonic titles continued to be used well into the Christian era in Egypt.

What, then, can we say about the title “Son of God” as applied to Jesus of Nazareth in the New Testament?

Because this expression is found in Hellenistic thought, some have suggested that this idea was simply appropriated by Hellenistic Jewish Christians.21

But the first time Jesus is called God’s son is in the baptism narratives (Matthew 3:16–17; Mark 1:9–11; Luke 3:21–22). Here the declaration of Psalm 2:7 (“You are my [beloved] son”) is combined with Isaiah 42:1 (“Here is my servant…I have put my spirit upon him”). When John the Baptist baptizes Jesus, the heavens open and the Holy Spirit or the spirit of God, depending on the gospel, descends upon Jesus in the form of a dove (as the spirit descended in Isaiah 42:1), and a voice from heaven proclaims (as in Psalm 2), “You are my beloved Son” (Matthew 3:16–17; Mark 1:10–11; Luke 3:21–22; John 1:32–34).

This event may be understood as a type of royal anointing ceremony like that undergone by Hebrew kings. The Gospels’ use of Psalm 2:7, a royal coronation psalm, certainly supports this hypothesis. Early Hebrew kings were anointed by a prophet, the spirit of God came upon the individual (see 1 Samuel 10:1, 10; 16:13) and, as Psalm 2 declares, the king is called the son of God. In other words, New Testament sonship Christology may be rooted in Hebrew concepts of kingship rather than in Hellenistic religious ideas imported from the Greek world.22

Christianity came early to Egypt. By the second and third centuries, it was found throughout the Nile Valley. For a very short time in the early fourth century (302–303 A.D.), Diocletian attempted to eradicate Christianity, but the Christian faith not only survived, it grew and actually dominated Egypt for the next three centuries.23 Perhaps it was because the Egyptians from pharaonic times through the Roman period believed their king was the “son of God” (that is, the son of Re, the incarnation of Horus) that the concept of Jesus as the incarnate Son of God, a central tenet of Christian doctrine, was more rapidly embraced in Egypt than in the rest of the Hellenistic world.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

André Lemaire, “Royal Signature: Name of Israel’s Last King Surfaces in a Private Collection,” BAR 21:06.

Hershel Shanks, “Magnificent Obsession: The Private World of an Antiquities Collector,” BAR 22:03.

Endnotes

Günther Dreyer, “Recent Discoveries at Abydos Cemetery U,” in The Nile Delta in Transition, ed. Edwin C.M. van den Brink (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Univ. Press, 1992), pp. 293–299; and “Horus Krokodil, ein Gegenkönig der Dynastie 0, ” in The Followers of Horus: Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman, 1944–1990, ed. Richard Friedman and Bryant Adams (Oxford: Oxbow, 1992), pp. 259–264.

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol. 1, The Old and the Middle Kingdoms (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1973), pp. 223.

Henri Gauthier, Livre des Rois, vols. 3–5 (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1916).

This is discussed by Eric Hornung in Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1982), p. 141.

Alberto Green, “Solomon & Siamun: A Synchronism between Early Dynastic Israel and the Twenty-First Dynasty Egypt,” JBL 97 (1978), pp. 353–367. See also James K. Hoffmeier, “Egypt As an Arm of Flesh: A Prophetic Response,” in Israel’s Apostasy and Restoration, ed. Avraham Gileadi (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988), pp. 79–85.

Kenneth Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 B.C.) (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1986), pp. 279–283.

Raphael Giveon, The Impact of Egypt on Canaan, Orbis biblicus et orientalis 20 (Freiburg: University Press, 1983); Hoffmeier, “Some Egyptian Motifs Related to Warfare and Enemies and Their Old Testament Counterparts,” in Egyptological Miscellanies: A Tribute to Professor Ronald J. Williams, ed. Hoffmeier and Edmund S. Meltzer; The Ancient World 6 (Chicago: Ares Publishers, 1983), pp. 53–70. The famous ivories from Megiddo, Samaria and Nimrud show Egyptian influence in the art, probably via Phoenicia (cf. Sir Max Mallowan, The Nimrud Ivories [London: British Museum, 1978], pp. 26–43). Notice the winged sphinxes wearing the Egyptian nemes crown surmounted by the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt on the ivories in Elie Borowski, “Cherubim: God’s Throne?” BAR 21:04.

F. Charles Fensham, “Father and Son as Terminology for Treaty and Covenant,” in Near Eastern Studies in Honor of William Foxwell Albright, ed. Hans Goedicke (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1971), pp. 121–135. Earlier on, Philip Calderone thought that Hittite treaty influence might be detected in 2 Samuel 7 (Dynastic Oracle and Suzertainty Treaty, 2 Samuel 7, 8–16 [Manila: Manila University, 1966], p. 51). For further discussion of Near Eastern treaty terminology, see Hoffmeier, “The Wives’ Tales of Genesis 12, 20 & 26 and the Covenants at Beer-Sheba,” Tyndale Bulletin 43:1 (1992), pp. 93–97 and references therein.

See Robert Gordon, I & II Samuel (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1986), pp. 239–240; A.A. Anderson, 2 Samuel (Waco: Word, 1989), pp. 122–123.

Lanny Bell, “Luxor Temple and the Cult of the Royal Ka,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 44 (1985), pp. 258, 267.

Keith Whitelam, “King and Kingship,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), vol. 4, pp. 45–46.

Donald Redford, “The Concept of Kingship During the Eighteenth Dynasty,” in Ancient Egyptian Kingship, David O’Connor and David Silverman (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 2 vols., pp. 157–159.

Rudolph Bultmann, Theology of the New Testament, 2 vols. (New York: Scribners, 1951–1955), vol. 1, pp. 128–129; Martin Hengel, The Son of God (London: SCM, 1976), pp. 21–56.

For different reasons, this suggestion is found in Oscar Cullman, Christology of the New Testament (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1963), pp. 272–275; James D.G. Dunn, Christology in the Making (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1980), pp. 12–64; Gerald O’Collins, Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1995), pp. 113–135.