To what extent were Jewish purity practices around the turn of the Common Era related to the Jerusalem Temple?

Scholars often associate purity concerns primarily with the Temple cult, since ritual purity was required of the participants. Both the priests serving in the Temple and the laypeople who ventured into the women’s court and beyond had to be ritually pure. Ritual purity was also necessary for eating sacred food, which applied to priestly families and laypeople eating portions of the offerings (Leviticus 7:20-21; Numbers 9:1-12).

Because of the stringent purity regulations concerning the sanctuary, many scholars assume that purity practices from an early time centered on the sanctuary. Basically, according to this view, purity regulations served to protect the sacred. Therefore, indications of purity practices far from the Jerusalem Temple at the end of the Second Temple period (516 B.C.E.–70 C.E.) are a new development. In addition, the strict purity praxis of the Pharisees (a group of lay teachers of Jewish law) and the members of the Qumran movement (a Jewish sect whose library was discovered in caves at Qumran next to the Dead Sea)a is also commonly understood as being motivated by priestly models. This reasoning similarly associates purity practices closely with the cultic sphere.

Nevertheless, others argue that purity practice was never primarily linked to the sanctuary (or sanctuaries). According to this viewpoint, many purity laws in Leviticus are not related to the cult in any way (e.g., Leviticus 11:24-40; Leviticus 14:33-53).1 Especially noteworthy is the requirement of a couple to wash themselves after sexual intercourse (Leviticus 15:18), which would have taken place far away from the Temple. Similarly, the obligation to purify (by sprinkling) on the third and seventh day after being in contact with a corpse would imply that purity mattered everywhere, at least in theory (Numbers 19). Leviticus rarely warns about defilement of the tabernacle (e.g., Leviticus 7:19-21; Leviticus 16:16).

When it comes to early Judaism, literary evidence indicates that many Jews practiced purity far from the Temple. For example, a connection between washing and prayer appears in some texts from the early second century B.C.E. and forward, such as the Book of Judith (12:6–9), the Third Sibylline Oracle (3:591–593; 4:162–166), and the Letter of Aristeas (305–306). Hand-washing before meals was common according to Mark 7:1-5, which agrees with early rabbinic traditions about hand-washing before meals and prayers. In addition, the Jewish philosopher Philo, who lived in Alexandria, emphasizes the need for washing after sexual relations before touching anything (Special Laws 3.63).

It is noteworthy that the rabbis continued to develop purity prescriptions after the destruction of the Second Temple and well after the hope for the rebuilding of the Temple had faded. Nevertheless, for key evidence demonstrating that Jews around the country practiced purity, scholars turn to the archaeological remains of stone vessels and mikva’ot (ritual baths; I prefer the label “stepped pools,” which does not imply a ritual function). As it turns out, however, the evidence is not as clear-cut as we would like.

Studying ancient stepped pools in Israel is a recent enterprise. The discovery of a mikveh (ritual bath) at Masada in 1964 was followed by many more such finds in the extensive archaeological excavations in Jerusalem beginning in 1967.b According to a survey from 2011, more than 850 stepped pools have been discovered in Palestine—in Judea as well as in Galilee. Most of them stem from the first century B.C.E. until 135 C.E., while a minority date to later periods. Yonatan Adler of Ariel University specifies that about 600 mikva’ot from this period have been discovered in Judea (including Jerusalem), while fewer than 70 stepped pools have been uncovered in the Galilee. Although they are primarily found in domestic spaces, some have been discovered near synagogues, wine and olive presses, and tombs.2 Overall, there is a gradual discontinuation of stepped pools from the late first century C.E. The majority of scholars agree that these pools were used for purposes of ritual purification.

The distribution of stepped pools in Judea and Galilee in the early Roman period coincides with the spread of stone vessels. Furthermore, the general use of these vessels follows a comparable chronological pattern to that of stepped pools: They enjoyed great popularity during the first century C.E. until 135 C.E., after which they taper off. Nevertheless, the production of stone vessels begins in the late first century B.C.E., that is, later than the introduction of stepped pools.

As with stepped pools, archaeologists’ interest in stone vessels arose during the late 1960s and the 1970s. Stone vessels are often understood as indicative of an intensified purity concern among Jews since, according to this standard line of thought, these would have been considered impermeable to impurity.c

Nevertheless, the literary support for the use of stone vessels in connection to purity is surprisingly meager. A key text is John 2:6: “Now standing there were six stone water jars for the Jewish rites of purification, each holding 20 or 30 gallons.” John’s aim is to explain why there were such large quantities of water at the wedding in the first place. The text does not indicate that the stone jars were used solely for purposes of purification, but it is evident that John associates quantities of water for purification—possibly for hand-washing—with stone jars.

The purity status of stone vessels is not mentioned in biblical laws, but rabbinic literature assumes that stone was insusceptible to defilement together with vessels made of dung and unfired earth (e.g., Mishnah ‘Ohalot 5.5; Mishnah Parah 3.2; 5.5). It is noteworthy that the connection between stone cups and hand-washing is not evident in early rabbinic literature. Mishnah Yadayim 1.2 implies that any vessel may be used to pour water onto the hands.

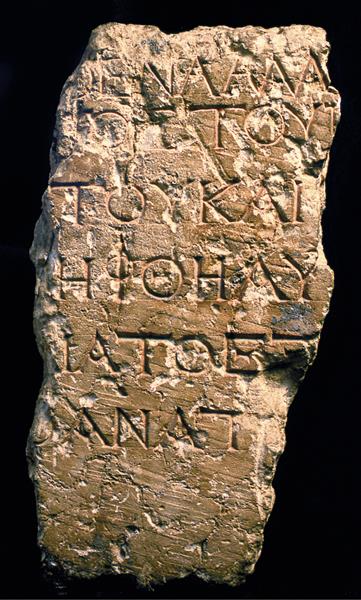

The earliest text that allegedly demonstrates that stone was impervious to impurity is found in the Damascus Document, which was an important document at Qumran judging from the 10 copies discovered there. It reads, “And all wood, stones, and dust which are defiled by human impurity while having oil stains on them, according to their impurity, he who t[o]uches them shall become impure” (Damascus Document 12.15b–17). The meaning is much debated: Does the law concern items made of these materials or all raw materials? Without going into detail, it makes sense to read the text quite literally as referring to natural materials.

In biblical law, impurity was transmitted easily via liquid (Leviticus 11:37-38). Accordingly, it is understandable why oil became a potent agent of defilement. The law in the Damascus Document clarifies that natural, raw materials, such as wood, stones, and dust, transmit impurity if there are oil stains on them (but not otherwise). Yet manmade items of these materials are still susceptible to impurity, which is obvious in the case of wooden vessels according to Leviticus 11:32; Leviticus 15:12).

Furthermore, the regulations in the Temple Scroll for purification of a house after the removal of a corpse (49.11–19) are illuminating. In this case, mills and mortar, which are made of stone, should be purified. It appears then that any item made of raw material (stone, dust, wood, etc.) would be susceptible to impurity in contrast to these materials in nature.3

In sum, early textual evidence supporting the theory that stone vessels would have been unsusceptible to ritual impurity is absent. We are then left with the vague association between purification and stone vessels in John 2:6, which was written at the end of the first century C.E. A clear opinion that stone vessels would be insusceptible to impurity doesn’t appear until early rabbinic traditions.

Stone vessels may have been popular for utilitarian reasons, as well as for fashion. All sorts of vessels and items were made of stone, such as tabletops, sundials, and ossuaries, evidently for reasons other than purity.4 In fact, the popularity of stone vessels may be due to the flourishing stone industry during and after the reign of Herod the Great.d It is possible that the rabbinic tradition that saw stone vessels as the ideal material for handling pure stuff and liquids represents a development of earlier, similar views, but this remains uncertain. Thus, the presence of stone vessels does not necessarily indicate a concern for purity.

There is less debate about the ritual function of stepped pools than there is of stone vessels. These early stepped pools display a great variety of styles and sizes, but all have steps leading down to a pool. Whereas some pools are divided in the middle by a partition or a double doorway, most are not. Only a few have an additional storage pool, otsar (“reservoir”).

Scholars often assess whether or not a stepped pool is a mikveh based on the Mishnah or even later rabbinic sources, which prescribe regulations concerning the minimum amount of water (40 seah, which may equal around 130 gallons) and the means by which they are filled (highlighting the importance of naturally channelled water as opposed to drawn water). But such an approach is anachronistic, since variety, not unity, marks these pools. In fact, in spite of the many rules about purification by water in early Jewish literature, there is only one known prescription about the requirements of an immersion pool: “Let no man bathe in water which is dirty or insufficient to cover a man; neither let him purify a vessel in it” (Damascus Document 10.10–12). It was a long process before ritual purification in a mikveh evolved into a formal institution. Originally the stepped pools may have served various purposes. Hints of “profane” uses of mikva’ot, such as cooling off and laundering, even appear in rabbinic literature.5

If so, we may then wonder: Why do these stepped pools appear around the turn of the Era? Moreover, do they indicate an intensified interest in purity? In order to answer these questions, we need to consider both the development of the washing methods for purification and the general Roman bathing culture.

There are two common means for a person to purify by water in the Torah: bodily washing and sprinkling. For purifying from corpse impurity, a person must be sprinkled with special water, “water of impurity” containing ashes from the red heifer (Numbers 19). Leviticus frequently prescribes ritual washing as means of purification. Two main verbs appear in this context: rakhats (Hebrew: רחץ) for bodily washing and kavas (Hebrew: כבס) for washing clothes. The verb rakhats has a wide range of meaning: wash, bathe, douse with water, and rinse off. In other words, we should not assume that the prescriptions concerning washing in water at an earlier stage necessarily implied immersing in water. Even the requirement of a semen emitter to “wash his whole body in water” does not necessarily mean to immerse (Leviticus 15:16).

We should also consider the physical landscape of the Judean hill country, far from the sea and lakes. We can assume that bathing was not part of regular, traditional activities. The Jewish traditions of bodily washing differed markedly from the Roman bathing culture, where bathing was an important element in the daily life and part of the national identity. Bathing was also part of the Greek culture, but the Romans perfected the art of constructing baths of various sizes and water supply systems in all corners of their empire.

Palestine witnessed the construction of many baths, mostly of modest size, from the early first century B.C.E. To understand this development, the general practice of washing and the Roman bathing culture must be taken into account. In comparison to the rest of the Roman Empire, there are no large public baths in Palestine from the early Roman period. This may be due to the issue of nudity. Jews and the neighbouring peoples did not want to encounter and socialize with other people in the nude as the Romans did. At the same time, private small baths, or tubs, were evidently not a problem in this regard, and there are many baths like that in Palestine.

Stepped pools are built not only in Judea and Galilee, but also in Samaria. Traditionally, people used to wash themselves in the courtyards of their houses aided by a basin, pouring water on themselves while standing or squatting in a basin, or bathed in springs or rivers. With the influence of Greek and Roman culture, however, the general trend turned toward bathing as a means of bodily washing. Accordingly, those who could afford it built bathtubs, stepped pools, sitting tubs, or large pools.6

Eventually, a standard for constructing pools evolved that was associated with ritual purification as promoted by the rabbis. This likely took place in the second century C.E., but even then there were diverse uses of stepped pools. Hence, in the late Second Temple period (516 B.C.E.–70 C.E.), Jews purified themselves in different ways, including going down into a stepped pool. In other words, the presence of stepped pools demonstrate that people washed themselves in new ways; it does not reveal much about whether people also cared about purity.

The spread of stone vessels and mikva’ot is commonly presented as key evidence that Jews were greatly concerned about purity everywhere. In contrast, I suggest that these do not reveal much about purity practices. In fact, there is no literary support for the popular view that stone vessels had the unique quality of being impervious to impurity. In addition, whereas many scholars assume that the spread of stepped pools demonstrates a heightened concern for purity beginning in the first century B.C.E., I hold that they appear as the result of the general bathing culture of the Greco-Roman world. From this perspective, the construction of stepped pools is evidence of a new trend in bodily washing, namely immersion, and not of any purity interest.

Did Jews practice purity far from the Jerusalem Temple at the turn of the Era? It is possible and even likely that many Jews did, but it is not set in stone.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. Edward M. Cook, “What Was Qumran? A Ritual Purification Center,” BAR, 22:06.

2. Ronny Reich, “The Great Mikveh Debate,” BAR, 19:02.

3. See Yitzhak Magen, “Ancient Israel’s Stone Age: Purity in Second Temple Times,” BAR, 24:05; Avraham Faust, “Purity and Impurity in Iron Age Israel,” BAR, 45:02.

4. Steven Fine, “Why Bone Boxes? Splendor of Herodian Jerusalem Reflected in Burial Practices,” BAR, September/October 2001.

Endnotes

1.

John C. Poirier, “Purity Beyond the Temple in the Second Temple Era,” Journal of Biblical Literature 122.2 (2003), pp. 247-265.

2.

Yonatan Adler, “Purity in the Roman Period,” The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Archaeology, vol. 2 (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2013), pp. 240-249.

3.

Vered Noam, “Stringency in Qumran: A Reassessment,” Journal for the Study of Judaism 40.3 (2009), pp. 342-355 (345).

4.

See Jürgen Zangeberg, “Pure Stone: Archaeological Evidence for Jewish Purity Practices in Late Second Temple Judaism (Miqwa’ot and Stone Vessels),“ in Christian Frevel and Christophe Nihan, eds., Purity and the Forming of Religious Traditions in the Ancient Mediterranean World, Dynamics in History and Religion, vol. 3 (Leiden: Brill, 2013), pp. 537-572 (553).