Tales from Tombstones

056

Amid the desolate, rocky wasteland of Biblical Zoar, Konstantinos Politis and others have discovered hundreds of remarkable tombstones that preserve detailed portraits of life—and death—among the Christians and Jews who once dwelled there. The often brightly colored and intricately decorated stones are a treasure trove of information about these two communities during the fourth to sixth centuries C.E. when Zoar (then known as Zoara or Zoora) was the seat of a major Christian bishopric and also home to a significant Jewish population.

In the accompanying article, two scholars expert in interpreting the epitaphs and iconography of these burial markers—Professor Steven Fine of Yeshiva University in New York and Kalliope I. Kritikakou-Nikolaropoulou of the National Hellenic Research Foundation in Athens, Greece—provide separate discussions of the Jewish and Christian tombstones of Zoar. Each examines the host of names, occupations and religious titles found within the communities, as well as the unique symbols and dating formulas that both groups used for their eternal memorials to the dead.

056

Jewish Grave Markers

Steven Fine

In Byzantine times a small but vibrant Jewish community lived among the much larger Christian community in Biblical Zoar, southeast of the Dead Sea. We know this from the surviving tombstones.

Zoar was a trip of but a day or so (by boat across the Dead Sea, as illustrated in the famous sixth-century mosaic church pavement known as the Madaba map) to much larger Jewish communities, like Ein Gedi, west and north of the Dead Sea. The Jews of Zoara, as it was called in the Byzantine period (fourth–sixth centuries C.E.), shared much not only with their co-religionists around the Dead Sea, but also with the Christians among whom they lived side by side.

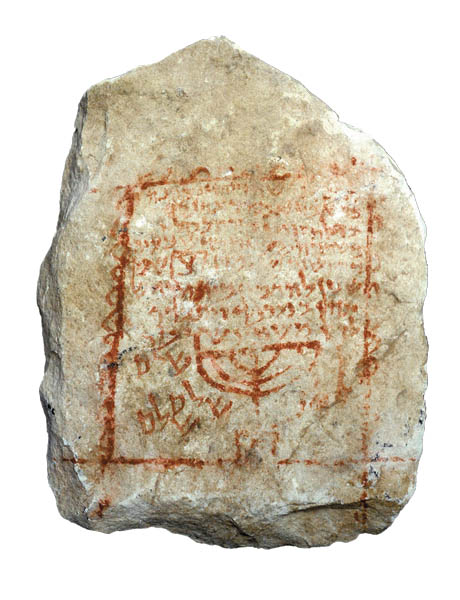

The Jewish graves are marked by tombstones about 8 inches wide and 16 inches high, some a bit larger, some a bit smaller. Most are inscribed and decorated with ochre pigment. A small number are incised. The Jewish tombstones are not unlike their Christian counterparts in this respect.

Otherwise, however, the tombstones of the two communities are different. The Christian tombstones are inscribed in Greek. Most of the Jewish ones are inscribed in a dialect of Aramaic known to scholars as Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, which was understood by Aramaic speakers, Jews and non-Jews, Samaritans, Christians or Arabs, when spoken. But these Jewish tombstones were inscribed in the square Aramaic script (shared with Hebrew) that was unique to Jews at this time. Thus only Jews could read these inscribed tombstones. They were internal documents, readable almost exclusively by Jews familiar with the Jewish script.

At least one Jewish tombstone, however, is bilingual, inscribed in Greek and Aramaic, and another solely in Greek. Surprisingly enough, it is this Greek inscription (see “Death at the Dead Sea”), as Dr. Politis notes in the previous article, that mentions an archisynagogos, a term for a synagogue leader well known from both Jewish inscriptions in Greek and other non-Jewish sources.

Other synagogue leaders are also mentioned in the corpus of Jewish tombstones from Zoar, including “rabbi” and hazzan. (Today the hazzan leads the congregation in chanting the prayer service, but the hazzan served a broader communal function in Byzantine-period synagogues.)

Other Jewish tombstones belonged to priests and Levites who, as today, herald hereditary titles derived from their cultic status in the Temple, giving us yet another inkling of the internal social hierarchy of the Jewish community.

The Jewish Aramaic inscriptions use very standard formulae. Near the beginning is the name of the deceased, followed by the day and month of death according to the Jewish calendar. The year of death is given according to two different systems: (1) the number of years since the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E.; and (2) the year of the Sabbatical cycle in which the fields must lie fallow for one year in seven. This is often followed by a concluding formula, for example: “Shalom (peace) unto Israel. Shalom” (Psalm 125:5 and parallels).

Many Biblical names were used by the Jews of Zoar as reflected on the tombstones, among them Jacob, Saul, Judah and Esther, as well as Greek and Nabatean names.

Here is the text of a typical tombstone—Hannah the daughter of Levi:

1. This is the tombstone of Hannah, daughter of

2. Levi, who died on Thursday

3. on the 19th day of the month of

057

4. Sivan, in the third year of the Sabbatical [cycle],

5. four hundred and two

6. years since the destruction of the Temple (= 472 C.E.).

7. Peace upon Israel. Peace.

A variety of decorative motifs appear on the tombstones, including birds and wreaths to frame the stone. Where Christians often employed the cross to denote their communal allegiance, Jews used images of the seven-branched menorah of the Temple, the ram’s horn (shofar) that is sounded on the Jewish new year; and the lulav (palm frond) and citron (a lemon-like fruit), symbols of the festival of Succoth (Tabernacles). The tombstone of Hannah daughter of Levi is typical. Its inscription is framed with a simple zigzag pattern. A large menorah is below, flanked on the left with a shofar and on the right with a lulav.

Jewish tombstones from Zoar have been known since 1925. Today, 31 of the stones found in secondary use (as part of other, later structures) have been published. Many more have come on the antiquities market, or have been acquired from local villagers by archaeologist Konstantinos Politis.

Christian Tombstones from Zoara

By Kalliope I. Kritikakou-Nikolaropoulou

The extraordinary discovery of numerous Christian tombstones in the cemetery extending south of the ruins of Byzantine Zoara has revealed evidence of one of the region’s earliest—and hitherto largely unknown—Christian communities.1

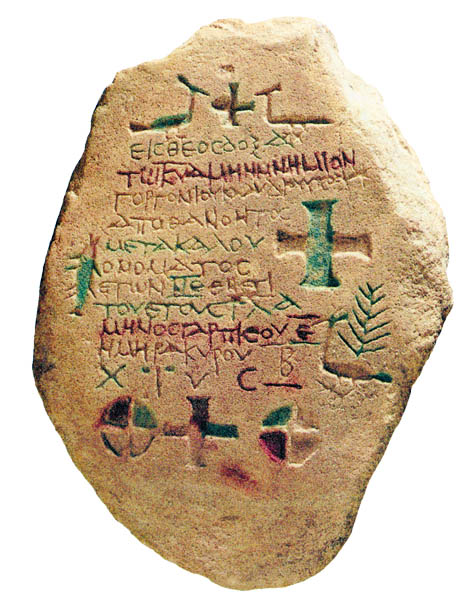

The more-than-400 funerary stelae, almost all of which are inscribed in Greek and date from the early fourth to early seventh centuries A.D., bring Zoara’s flourishing and well-organized early Christian community into focus, while also offering insightful comparison with the area’s contemporaneous Jewish community.

The generally rectangular tombstones, most of which stand about a foot and a half high, are made from local sandstone and were found reused in later tombs. They carry several lines of incised text, often colored red and sometimes green, which are typically placed within a decorative border or frame. The majority of the gravestones are embellished with simply engraved but brightly painted patterns and symbols. The earliest and most predominant symbol is the cross, but a variety of other motifs are depicted, including various Christograms, birds (mainly doves and peacocks), fish, palm branches, vines and even a ship. These typical early Christian symbols, which allude to Christ and the heavenly life, illustrate the deceased’s Christian faith and belief in the soul’s salvation in the afterlife.

The formulaic epitaphs are generally introduced by the Greek word mnēmeion (“monument”), followed by the name, patronym and age of the deceased, as well as the exact date of death. Year of death was reckoned according to the years elapsed since Trajan’s establishment of the province of Arabia (106 A.D.). The month and day of death was given according to the local Greco-Arabic calendar, which started on March 22 and consisted of 12 058 Macedonian months of 30 days each, plus five intercalary (leap) days. The weekday of death was recorded either by its planetary name, e.g., hēmera Selēnēs (“day of the Moon” = Monday), or its numerical one, e.g., hēmera Kyriou deutera (“second day of the Lord” = Monday). Finally, around the mid-fifth century, indiction, a dating element based on the 15-year taxation cycle of the late Roman Empire, was regularly added to the date of death. The indiction year began on September 1 and was individually numbered on the tombstones, e.g., indiktiōnos prōtēs (“[in the] first indiction [year]”).

The Christian character of the monuments is also apparent in the various religious or funerary acclamations and invocations. The phrase heis Theos (“one is the God”), a confession of monotheistic belief, appears at the beginning of more than a hundred epitaphs, while several expressions convey Christian faith and servitude, e.g., apothanontos meta kalou onomatos kai kalēs pisteōs (“he who died having a good name and good faith”), anepaē en Christō (“she came to rest in Christ”) and Kyrie, anapauson tēn psychēn tēs doulēs (“Lord, rest the soul of [your] female servant”).

A common conclusion to the inscriptions is the consolatory acclamation tharsei, oudeis athanatos (“be of good cheer, no one is immortal”).

The approximately 300 names recorded on the tombstones demonstrate the Hellenization and eventual Christianization of Zoara’s indigenous population. Many are Hellenized versions of Semitic names, including Nabatean names like Abdalgēs, Dousarios and Obodas, as well as Biblical names like Ioannēs, Iakobos and Anna. Purely Greek and Hellenized Latin names, mainly derived from the Christian tradition, are also attested, the most popular being the names Petros and Paulos, respectively, referencing the apostles Peter and Paul.

The gravestone epitaphs also provide a nearly complete list of the ecclesiastical officials of the Christian community of Zoara. Among the titles given are reader, subdeacon, deacon, deaconess, archdeacon, presbyter, archpresbyter and bishop. In addition, several gravestones, especially the epitaph of the bishop Apsēs (or Apsis), who died on July 29, 369 A.D. and is the earliest bishop known at Zoara, offer epigraphic testimony to the early date of the city’s bishopric, which survived until the end of the seventh century.2

Also found among the deceased are military officers of both high and low rank stationed at Zoara, including a tribunus, a primicerius, a praepositus and a draconarius. There are six additional persons from neighboring cities who happened to be buried in Zoara.

Finally, the constant references to the deceased’s age and precise date of death provide us with an unparalleled picture of life and death among Zoara’s Christian population. Although ages at death ranged from 8 months to 108 years, most women died between the ages of 15 and 24 (the prime childbearing years), whereas men generally survived into their late 20s and early 30s. About 17 percent of Zoara’s children died as infants. The extremes of winter (December–January) and spring (April–May) often brought disease and death.

A few epitaphs mention or date to a catastrophic event known from historical sources, that is, the severe earthquake of May 18, 363 A.D., which devastated much of southern Palestine and claimed countless lives, including as many as seven residents of Zoara.

Amid the desolate, rocky wasteland of Biblical Zoar, Konstantinos Politis and others have discovered hundreds of remarkable tombstones that preserve detailed portraits of life—and death—among the Christians and Jews who once dwelled there. The often brightly colored and intricately decorated stones are a treasure trove of information about these two communities during the fourth to sixth centuries C.E. when Zoar (then known as Zoara or Zoora) was the seat of a major Christian bishopric and also home to a significant Jewish population. In the accompanying article, two scholars expert in interpreting the epitaphs and iconography of these burial markers—Professor […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

For a comprehensive study of these tombstones, which were entrusted by Dr. Konstantinos Politis for publication to Dr. Yiannis Meimaris of the National Hellenic Research Foundation in Athens, Greece, see Yiannis E. Meimaris and Kalliope I. Kritikakou-Nikolaropoulou, Inscriptions from Palaestina Tertia, vols. Ia and Ib (Supplement). The Greek Inscriptions from Ghor es-Safi (Byzantine Zoora). Meletemata 41, 57 (Athens 2005, 2008).

See Yiannis E. Meimaris and Kalliope I. Kritikakou-Nikolaropoulou, “The Greek Inscriptions,” in Konstantinos D. Politis, ed., Sanctuary of Lot at Deir ‘Ain ‘Abata in Jordan. Excavations 1988–2003 (Amman 2011), pp. 388–389. See also Konstantinos Politis, “Where Lot’s Daughters Seduced Their Father,” BAR 30:01, p. 28.