That Ol’ Time Religion

American folk artists depict apocalyptic texts

036037

Down dusty rural roads and in inner-city housing projects, American folk art has always flourished. Folk artists may be teenagers just beginning their lives, or they may be octogenarians who knew grandparents emancipated from slavery. Some of them work as janitors in bakeries; some farm the land. One, a quadriplegic, wields a paintbrush in his mouth, and another weaves miniature tapestries from threads of unraveled socks while serving time. These artists are as diverse as American society, yet some of their creations have certain themes in common: the struggle against social injustice, the trauma of 037drugs and alcohol, and a passionate religious conviction rooted in the Bible.

Though each folk artist is unique, as a group they usually lack formal artistic instruction. They tell their stories with highly individual visual languages invented from unfettered imaginations. Their creations may be mud on plywood or sculptured garbage—but their pioneering spirits impel them to weave tales in ways that are immediately accessible to the rest of us. Their highly personal expression—known in the United States as “folk art” or “visionary art” and in Europe as “art brut” or “naive 038art”—is found in virtually every culture.

In the past decade, interest in American folk art has exploded. In 1990, fewer than 10 museums included contemporary folk art in their collections; today more than 50 museums vie for the best folk art America offers. Three years ago, Folk Fest, an annual folk art trade show in Atlanta, Georgia, struggled to establish an identity; last August it attracted more than 80 dealers and 7,500 collectors. The star of last year’s Folk Fest, the now-frail Reverend Howard Finster, had fans clamoring for his autograph and standing in line for more than an hour to meet him.

The 80-year-old Reverend Finster, a Georgia artist, considers himself the Noah of the modern age. “In a way, I am having more success than Noah had,” Finster says. “He preached to the world, but he didn’t get a one of them saved…People are getting saved today, ‘cause they are writing and telling me, ‘Howard Finster, we seen your work and heard you out.’”

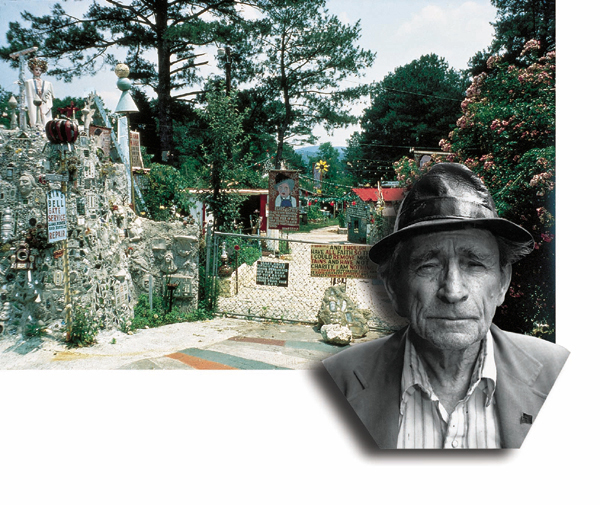

Reverend Finster first stepped up to the pulpit when he was “born again” as a teenager in rural Alabama—but it was not until 1976, at the age of 60, that he saw a dab of paint on his finger become a face that commanded him to “make sacred art.” Heeding this instruction, Reverend Finster launched his career as an artist, teaching himself to draw, paint and construct assemblages with the materials at hand.

Reverend Finster has spent the last two decades painstakingly creating Paradise Garden at his home in Summerville, Georgia. Paradise Garden, which he says was “commissioned from God,” is a lush, modern-day version of the Garden of Eden, a rendering of Finster’s fantastic visionary world. The two-acre maze is packed with a blinding array of sculptures and structures assembled from rusted bicycle parts, kitchen appliances, old typewriters, Coke bottles and endless bits of junk. Finster uses house paint and markers on plywood in most of his 039works. Henry Ford, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, William Shakespeare, virtually every species of the animal kingdom and a healthy assortment of angels and religious figures assume starring roles. Scattered amongst the chaos are huge signs proclaiming “Heaven is worth it all” and “Trying to get people back to God before the end of Earth’s planet.” Placards implore “Must Jesus bear the cross alone?” The crowning glory of Paradise Garden is Reverend Finster’s spectacular 5-story, 16-sided World’s Folk Art Church, which looms over the Garden like a surreal wedding cake.

At last count, Finster had made more than 40,000 pieces (he meticulously numbers each one). Each piece is part of his crusade to save the world before it is too late. And his message is spreading, as stated on a bust of Elvis Presley Finster painted in 1987: “My work is going out from the Garden like a flowing river on camery pictures in slides. movys. and family picures. by t.v. radio newspapers. and magazines. and people telling the garden story all over the country.”

040

Reverend Finster has become a celebrity far beyond Summerville, Georgia. He’s appeared on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and popular music groups, such as R.E.M. and the Talking Heads, have decorated their album covers with his artwork and have filmed music videos on the grounds of Paradise Garden. This large-scale exposure has helped Reverend Finster fulfill his aspiration to be a modern-day Noah; it has also made him an icon of popular culture, a next-generation Andy Warhol.

Speaking about religious themes in contemporary American folk art, Roger Manley, guest curator for a current exhibition—The End is Near!—at Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum, writes:

In one way or another much self-taught art has dealt with individual calamity, visionary experience and emotional transformation by presenting these against a backdrop of universal destruction and personal revelation. Since religion focuses on these same human predicaments—suffering, death, transformation, concern for the future, and deeper meanings—it is no wonder that self-taught art (like most art down through history) has shared much of its symbolism and imagery with religion, while often drawing inspiration from intensely private systems of thought.1

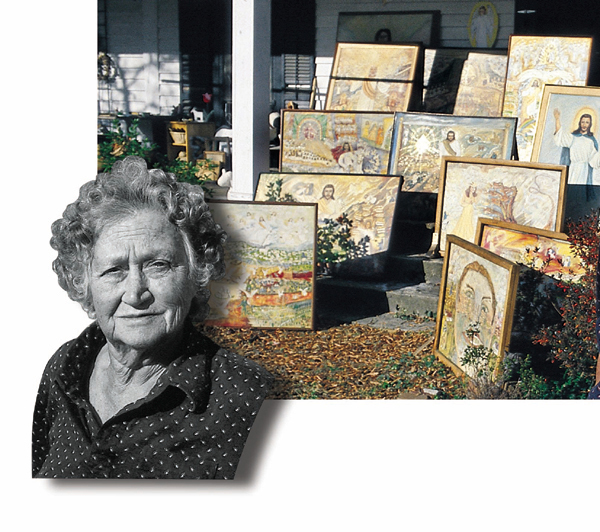

At least two other self-taught artists from the South are inspired by deeply held private beliefs. 041Myrtice West has been driven by her faith for all of her 73 years, but with much less fanfare and showmanship than has Reverend Finster. West enjoyed art as a childhood hobby but turned to painting in earnest in her 50s, as a way of coping with tragedies in her life. Raised on a cotton farm in rural Alabama, she dropped out of school in the eighth grade and married sharecropper Wallace West at the age of 17. Her fierce desire to have a family was foiled by miscarriage, cancer and surgery, leading her doctors to predict that she would never be able to bear a child. But like Hannah, the mother of the prophet Samuel, West prayed earnestly to God for a child. And, as with Hannah, her prayers were answered. When she was 34, she gave birth to her only child, Martha Jane.

“Between Jesus and my baby I prayed almost daily without stopping,” West said. “Anytime death or danger faced my child, in prayer I clung to Jesus desperately begging to stay close enough to feel his presence.” Martha Jane gave West reason to pray. Against her parents’ wishes, the 15-year-old married her high school sweetheart, a hot-tempered young man named Brett Barnett. Brett grew increasingly abusive until Martha Jane finally left with their two children after nearly a decade of marriage. Soon after, at Martha Jane’s birthday party, Myrtice West and her family watched in stunned horror as Brett shot Martha Jane five times, killing her.

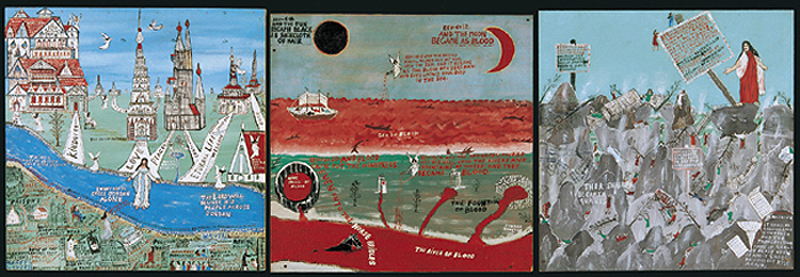

The Wests were left with the devastating task of burying their only child and the challenge of raising their two grandchildren. Although West had often turned to art as a way of coping—painting portraits of Jesus and doves, and landscapes of remembered scenes from her youth—she now felt God was sending her a message to paint. Having no formal ties to any church, West began studying the Book of Revelation on her own. She decided she would attempt to paint a series covering all 22 of its chapters. After seven years studying the Bible and painting every day, West finished her Revelation series, with 14 large oil paintings on wood and canvas.

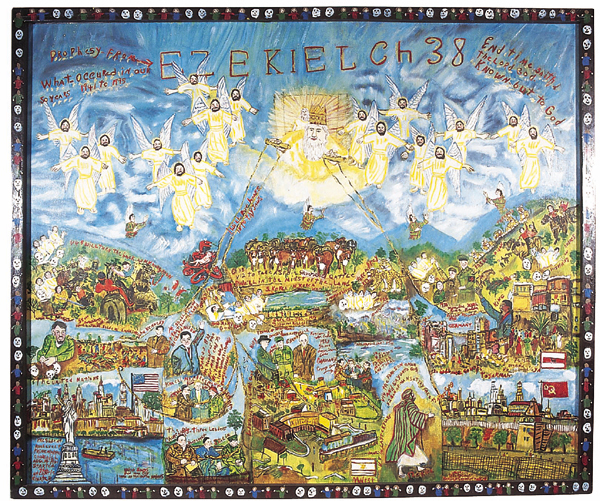

West is unequivocal about her reasons for devoting her life to painting. “I started my Revelation series to keep from going crazy. I turned to God 042rather than let Satan drag me down.” She sees her painting as a gift from God and hopes that her works will educate others about his word: “I am trying to do everything I can for God, because he’s done so much for me.” Since completing her Revelation series, West has gone on to paint the Books of Ezekiel and Daniel. Like the Book of Revelation, these biblical books are especially full of apocalyptic visions.

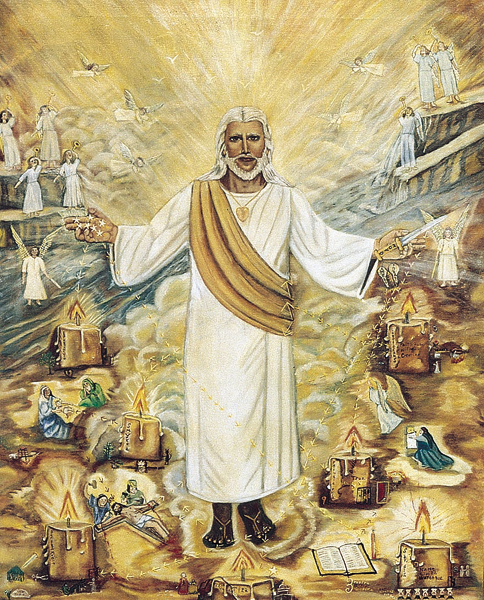

A look at West’s first Revelation painting alongside her later works reveals a fascinating evolution in her style. Her rendering of Revelation 1 is a straightforward, imposing image of Jesus with seven candles. The imagery and scant text that serve as a backdrop to the image come from the first three chapters of Revelation, but the piece is primarily a visual interpretation of Revelation 1:12: “Then I turned to see whose voice it was that spoke to me, and on turning I saw seven golden lampstands and in the midst of the lampstands I saw one like the Son of Man, clothed with a long robe and with a golden sash across his chest.” In stark contrast, West’s later paintings are detailed road maps of scenarios and 043narrative; they lack the central focus and single image seen in her earliest Revelation pieces. West thickly covers her later paintings with numerous images from the words of the book and chapter being interpreted, accompanying these depictions with labels and verse references.

In her painting Ezekiel, Chapter 38, West breaks from her normal style to deliver her clearest message yet to contemporary America. It is one of the only images in which she sees a prophetic vision manifested in recent historical events. West references numerous verses while depicting major events and figures of the latter half of the 20th century: the creation of Israel; the Korean and Vietnam wars; Martin Luther King, Jr.; the Camp David Summit; and the recent peace agreement between Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat. She portrays all of these in the context of the Cold War, with the Soviet Union as the great nation Magog and the United States, along with the United Nations, as a stronghold through which God works.

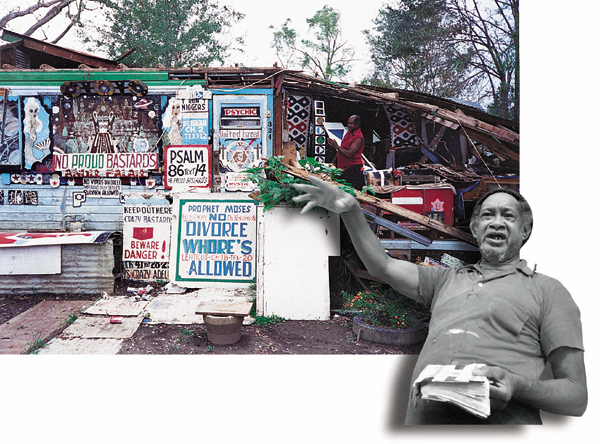

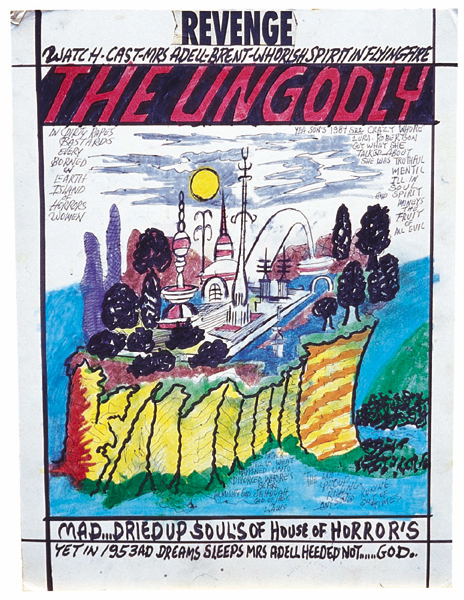

West’s detailed and precise renderings stand in stark contrast to Finster’s freeflowing visual sermons—but they look like kin when compared with the chaotic art of the self-acclaimed Prophet Royal Robertson. A Louisiana native, Robertson was in his early 60s when he died this July. Apparently, he worked intermittently as a sign painter and field hand. The details of his life as he told them are sketchy and confused, woven in with dream images that blend fantasy and reality. About all that is known for sure is that he married a woman named Adell Brent in about 1955 and that Brent left him after two decades of marriage. Brent’s departure, which in Robertson’s mind took place under a cloud of unfaithfulness, became the catalyst for his 044ongoing struggle against evil, which manifests itself through his art.

Robertson, who lived alone in a rural prefabricated home without a telephone, produced hundreds of paintings and drawings on posterboard. Like Reverend Finster’s Paradise Garden, the grounds of Robertson’s home became a canvas for self-expression. Whereas Paradise Garden welcomes visitors with assurances that life is eternal and full of glory if one gets right with God, a walk in Robertson’s environment was a journey through the paranoia and despair of his attempts to exorcise the demons traumatizing him. Bold signs littered his yard proclaiming “The End of the World,” and other, often obscene, admonishments. On one weathered sign appears the advice “Beware they all over cities of America—Demon’s taken over man womens soull’s/soul’s of lofty proud Satan/beware night dances.”

Whereas Finster and West write out text and verse, Robertson only referred to the Bible in shorthand. Among his favorite references were “James 4 TEXT 4” and “Proverbs 2 ALL.” The James passage is one of the harshest condemnations of adulterers in the New Testament, while the Proverbs passage describes how wisdom “will save you also from the adulteress.” His other references included virtually every verse that speaks poorly of women, and myriad allusions to adulterers and prostitutes.

Though Robertson sometimes referred to other themes, like the Day of Judgment and deliverance from his enemies, it is on matters of unfaithfulness that he was as thorough as a concordance. He had scoured his tattered, dog-eared Bible for every passage he could find to support his hatred of his ex-wife and his growing suspicions of all those around him. The references in his art portray both his search for an answer and his line of defense against a world of evil schemes. And together they show his prophetic belief that the world will be judged harshly and destroyed utterly and that he will be vindicated.

West’s and Robertson’s art muster their faith against the world’s flood of troubles. Neither began with aspirations to be an artist; they were simply responding to a primal urge borne of visions and zeal, to interpret and share their convictions and to exorcise internal demons. Their paintings are a kind of catharsis, a coming to terms with senseless violence. Reverend Howard Finster, on the other hand, expands his call to evangelize with every painting and sculpture he creates, in the finest tradition of southern revivalism.

Fantastic visions have driven these three folk artists, just as visions drove Noah, Daniel and Elijah. Their art speaks out against the evils of this world, showing apocalyptic images of the revelation of God’s justice. Their art looks to the end of the world.

“God is in control,” West asserts with conviction. “Evildoers will be punished,” Robertson added with vitriol. And Finster preaches, over and over again, “Get right with God.” These messages are not that far from the words of a certain desert prophet, John the Baptist, who two millennia ago proclaimed, “The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent and believe the good news!”

Down dusty rural roads and in inner-city housing projects, American folk art has always flourished. Folk artists may be teenagers just beginning their lives, or they may be octogenarians who knew grandparents emancipated from slavery. Some of them work as janitors in bakeries; some farm the land. One, a quadriplegic, wields a paintbrush in his mouth, and another weaves miniature tapestries from threads of unraveled socks while serving time. These artists are as diverse as American society, yet some of their creations have certain themes in common: the struggle against social injustice, the trauma of 037drugs and alcohol, and […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username