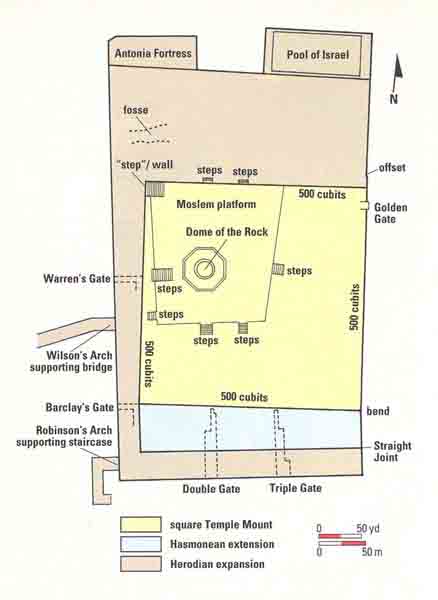

Four years ago, I wrote an article for BAR in which I identified the original 500-cubit-square Temple Mount.1 By now, this location is well established in the archaeological world, having been adopted, for example, in the latest edition of the archaeological encyclopedia of the Holy Land published by the Israel Exploration Society.2

My goal was always more than this, however. I was convinced that it was possible, on the basis of these findings, to locate the site of the Temple itself. The method of working from the outside in, in relation to the Temple Mount, had been sanctioned by the success of this discovery. Having narrowed down the search to this square, it would be logical to trace the location of the actual Temple from the archaeological remains found in this reduced area. Close familiarity with the Biblical and extra-Biblical sources on the Temple, gained from years of prior research into the Temple Mount, would ensure that the emerging picture could be tested against the reality of history.

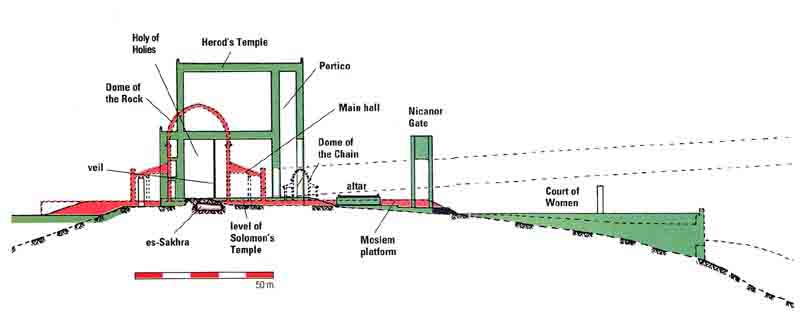

At the end of my BAR article, I briefly discussed the location of the Temple. Based on then-preliminary considerations, I placed it, not in the center of the original Temple Mount, but over the rock mass lying beneath the Dome of the Rock, generally referred to as es-Sakhra, “the Rock” in Arabic. But, as I wrote then, I intended to refine my proposal still further. This article is the fulfillment of that promise.3

Moreover, as the research gathered its own momentum, other questions that I had not even considered could be answered were unexpectedly resolved. I now believe that, without having gone in search of it, the research has directed us to the very spot where the Ark of the Covenant stood within the Holy of Holies.

My reasons for placing the Temple over es-Sakhra are briefly as follows: Few would contest that Herod’s Temple stood on the same site as that of Solomon. Herod’s Jewish subjects barely allowed him to rebuild the Second Temple—a change of site would have been inconceivable. The first-century Jewish historian Josephus tells us that Herod’s Temple was built at the top of the mountain.4 It is clear to anyone who visits the site or who examines a photograph of the area that the Dome of the Rock enshrines the rocky summit of the mount.

Placed here, with the Holy of Holies over es-Sakhra, the courtyards on the four sides of the Temple conform to their relative sizes as specified in Middot, a tractate of the Mishnah (the earliest rabbinic codification of the law, from about 200 A.D.). According to Middot 2.1, “The Temple Mount was 500 cubits by 500 cubits. Its largest [open space, i.e., courtyard] at the south, second largest at the east, third largest at the north and least at the west.” These requirements can be satisfied only if the Holy of Holies of the Temple is placed over es-Sakhra.a

Middot 4.6 also tells us that the foundation of the Temple was 6 cubits, or about 10 feet, high. That is an unusually high foundation. The Rock now stands almost 6 feet above the floor of the Dome of the Rock. If we take into consideration that the bedrock is located another 3 feet 3 inches (1 meter) below the floor, then the rock would stand at least 9 feet above its immediate surroundings. That this is in fact the case is demonstrated by a re-examination of an 1873 report by the French scholar Charles Clermont-Ganneau. Clermont-Ganneau tells us that he witnessed a small excavation near the eastern door of the Dome of the Rock in which he saw terra rossa, the typical red earth found immediately above bedrock, at a depth of 2 feet (57 centimeters) below the paving in this area. The excavation continued to a depth of 3 feet (90 centimeters), but bedrock was still not encountered, although the feeling was that it could not have been far away.5 Furthermore, in 1959 the Italian Franciscan scholar Bellarmino Bagatti noticed bedrock at several places below the floor during extensive repair operations conducted at that time. According to his observations, the general appearance of the Rock was that it was level but dipped down towards the outer walls of the Dome of the Rock. As the outer face of the walls of the Temple were located 25 cubits (41 feet) away from the foot of es-Sakhra (Middot 4.7), we can therefore safely add at least another foot to the 9 feet just mentioned, bringing the total difference in height between the top of es-Sakhra and the outer walls of the Temple to just over 10 feet—which is exactly 6 cubits. Now we can understand why the Temple required a foundation 6 cubits high—so that the floor of the Temple would be at approximately the same level as the top of es-Sakhra, where the Ark of the Covenant could be placed in the Holy of Holies.

From the moment I identified the original Temple Mount, I knew that if I were to go further I would need to research and analyze es-Sakhra down to its minutest detail.6 I also knew that this was going to be a formidable task, as no previous systematic archaeological research had ever been carried out on this rock mass. Israeli archaeologists, who have been eager to study every stone of the Holy Land and especially of Jerusalem, have avoided es-Sakhra like the Biblical plague sent to punish King David for taking a census (see 2 Samuel 24). Obviously the political sensitivities of the Temple Mount area are one problem. In addition, the seemingly intractable problems involved in its interpretation make it a veritable scholarly terra incognita, despite the fact that the site is the focus of three major world religions.

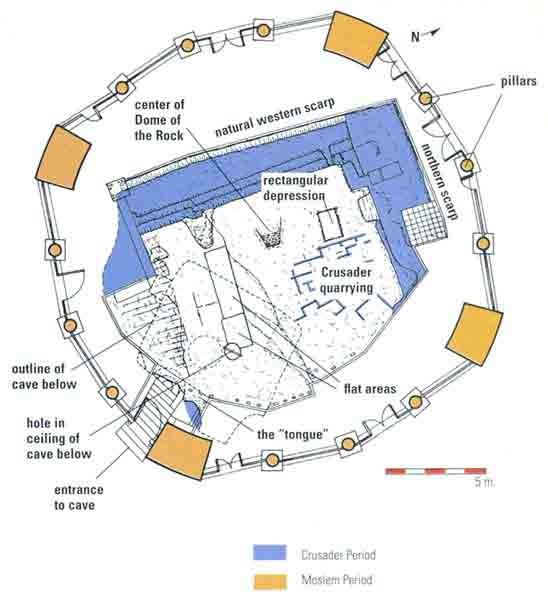

My first task was to try to make an accurate plan of es-Sakhra. I began with the measurements and description the German scholar Gustaf Dalman made in 1910.7 Dalman’s plan in fact proved to be highly accurate, as he was actually allowed to walk on es-Sakhra for ten minutes. In a series of subsequent visits, he made further measurements by stretching tapes over the rock with the help of a mosque attendant who stood inside the fence. Based on my own observations and photographs taken from the ambulatory, high above, under the dome, I then added new features. As far as measurements are concerned, I have found that pacing out the dimensions of a structure can be very accurate. It is a method I have used for a long time when circumstances do not allow for a full survey. My normal step for measuring is 95 centimeters, or 3 feet 1 inch.

The next task was to try, based on this plan, to reconstruct es-Sakhra as it had existed in the First Temple period. Such an exercise, of course, requires an understanding of the Temple’s history—indeed, Jerusalem’s history—through the ages. The original appearance of es-Sakhra can be deduced only by eliminating all the changes made to it since it was housed in Solomon’s Temple.

Through all the vicissitudes of the site during the time of the First and Second Temples, it appears from the sources that whenever the Temple was despoiled or damaged it was always built up again. So it was that the damage inflicted on it by the immediate predecessors of King Joash was followed by his extensive repairs under the guidance of Jehoiada the high priest (2 Kings 12:1–16; 2 Chronicles 24:1–14). Later, the earthquake damage that affected the Temple in the last year of King Uzziah was partially repaired by King Jotham (2 Kings 15:35; 2 Chronicles 27:3). Again, the Sanctuary was cleansed by King Hezekiah (2 Chronicles 29:3–19) after the replacement of the scripturally prescribed altar by one brought in from Damascus by King Ahaz. Following on the perilous times of the reign of Manasseh and his son Amon, when the Ark of the Covenant was apparently removed by the priests for safekeeping, their successor Josiah had the Ark restored to the Holy of Holies (2 Chronicles 35:3). The Babylonian destruction of the Temple in 586 B.C. was followed by its reconstruction by Ezra, Jeshua, Zerubbabel and Nehemiah after a 70-year exile in Babylon. The plundering of the Temple by Antiochus Epiphanes and his sacrilegious offering of a swine on the altar was followed by its rededication by the Maccabees in 164 B.C. (1 Maccabees 4:36–61; 2 Maccabees 10:1–8) and an extension of the Temple platform under the Hasmonean dynasty.b

It appears that throughout this period whatever happened to the site was well documented: Damage to the Temple consisted of a breaking down of its walls or robbery of the Temple treasures. At worst, a pagan image was installed inside the Holy of Holies, as was probably the case during the reign of Manasseh (2 Kings 21:7; 2 Chronicles 33:15). The sources give us no reason to believe that there was any change in es-Sakhra or in the alignment of its foundations. Herod’s rebuilding of the Temple, which commenced in 19 B.C. and which was completed approximately half a century later, afforded es-Sakhra further protection until its destruction by the Romans in 70 A.D. Herod simply took away the old foundations of the Temple and replaced them with new foundations 6 cubits high.8

I knew that we would have to look closely at what had befallen the Temple site during the Roman period. In the fourth decade of the second century, after the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 A.D.), the emperor Hadrian rebuilt Jerusalem, which he renamed Aelia Capitolina, and made it a Roman city from which Jews were barred. Two writers of the period, Dio Cassius and Jerome, mention a Temple of Jupiter built on the site of the Jewish Temple. Eyewitnesses, such as Origen and the Pilgrim of Bordeaux, mention two statues, at least one of which represented the Emperor Hadrian. Apart from this, the Temple was all but ignored during this period.

In 324 A.D. the Byzantine period began in Palestine, with the unification of the empire under Constantine. Constantine Christianized the empire. During the Byzantine period the Temple Mount was left in ruins as a sign that, as the early Christians believed, God had abandoned the Jews; the site therefore had no further relevance.

When Jerusalem was taken by Caliph Omar in 638 A.D., he found that es-Sakhra had been used as a dunghill, which took great Arab labor to clean.

Then, with the construction of the Dome of the Rock in the late seventh century and the reverence accorded to es-Sakhra by the Moslems, its protection was assured until the coming of the Crusaders. In 1099, the Crusaders wrested the Dome of the Rock from the Moslems and converted it into a church called Templum Domini. A cross then graced the top of the dome.

Most of the changes I detected in es-Sakhra can be attributed to the Crusader period. The history books suggest as much. According to one contemporaneous account, the reason the Crusaders mutilated the rock was that when they first saw es-Sakhra, “It disfigured the Temple of the Lord.”9 When the Crusaders transformed the Dome of the Rock into a church, they cut away parts of es-Sakhra to make it more aesthetic in the eyes of westerners. They also quarried a broad staircase from the bedrock leading up to es-Sakhra on the west, so that the High Altar, which stood on top of es-Sakhra, could be reached more easily. At this time the entire rock mass was covered with marble slabs.

After Jerusalem fell to the Egyptian-Turkish Sultan Saladin (Salah ed-Din) in the late 12th century, Moslem historians clamored in their denunciation of what the Crusaders had done to the Rock. One of them described not only what the Crusaders had done, but how the Sultan had tried to undo the damage: “As for the Rock, the Franks (Crusaders) built over it a church and an altar, so that there was no longer any room for the hands that wish to seize the blessing from it or the eyes that long to see it. They had adorned it with images and statues, set up dwellings there for monks and made it into a place for the Gospel, which they venerated and exalted to the heights. Over the place of the Prophet’s [Mohammed’s] holy foot they set up an ornamental tabernacle with columns of marble, marking it as a place where the Messiah [Jesus] had set his foot; a holy and exalted place, where flocks of animals, among which I saw a species of pig, were carved in marble. The Rock, the object of pilgrimage, was hidden under constructions and submerged in all this sumptuous building. So that the Sultan ordered that the veil be removed, the curtain raised, the concealments taken away, the marble carried off, the stones broken, the structures demolished, the covers broken into. The Rock was to be brought to light again for visitors and revealed to observers, stripped of its covering and brought forward like a young bride. Before the conquest only a small part of the back of it was exposed, and the Unbelievers [Crusaders] had cut it about shamefully; now it appeared in all its beauty, revealed in the loveliest revelations.”10

The Crusaders had also chipped away at the Rock to raise money. These rock chips they would sell back in Europe for an equal weight of gold. As reported by an Arab historian, “The Franks had cut pieces from the Rock, some of which they carried to Constantinople and Sicily and sold, they said, for their weight in gold, making it a source of income. When the Rock reappeared to sight, the marks of these cuts were seen and men were incensed to see how it had been mutilated. Now it is on view with the wounds it suffered, preserving its honor forever, safe for Islam, within its protection and its fence.”11

Since the time of Saladin, es-Sakhra appears to have remained untouched. Although Saladin removed the paving, the icons and other Crusader additions from the Dome of the Rock, he left the wrought-iron screen that stood between the columns of the inner circle of the Dome. This screen remained until the restoration of 1963.

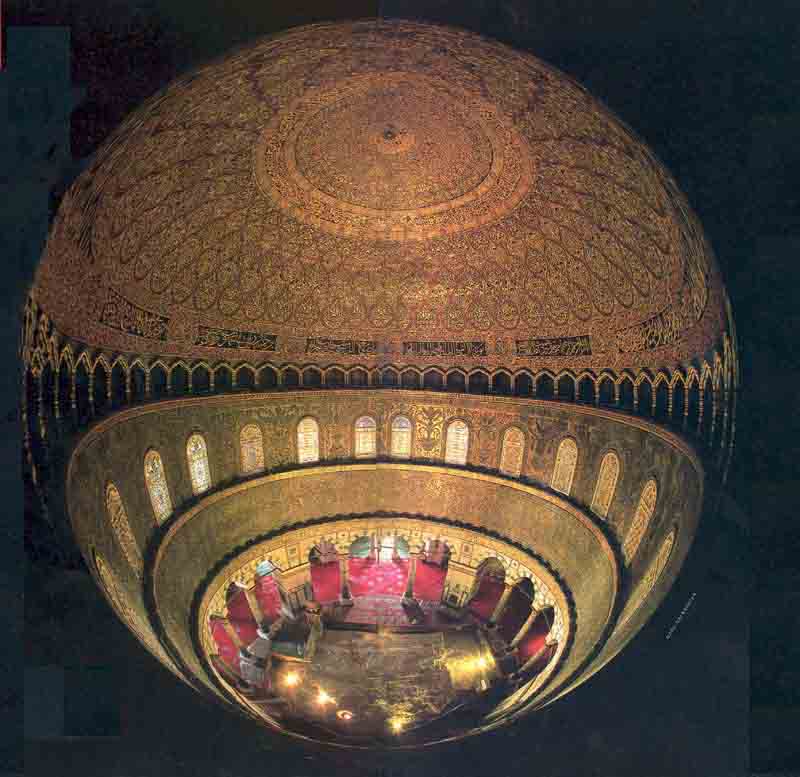

Es-Sakhra is now surrounded by a wooden balustrade and may be viewed only from outside this enclosure. This makes looking at details difficult. The Rock with its balustrade lies under the great golden dome, which is supported by four major piers and 12 columns, three on each side, between the piers.

As mentioned before, the Rock itself stands almost 6 feet above the floor of the Dome of the Rock. The main entrance to the Dome of the Rock is on the west, so that one naturally approaches es-Sakhra from that direction. Looking at it from the west, it appears that the shape of es-Sakhra has been changed to look like a square block and fit exactly in the middle of the four major piers that support the dome. Before that happened, however, es-Sakhra must have looked almost like a circle with the pillars surrounding it.

Beneath the rock, under the southeastern quadrant, is a cave known as Bir el-Arwah, the “Well of Souls” (marked by a dotted line on the plan). It has an irregular squarish shape—about 24 feet in either direction. The ceiling looks natural. The height varies from about 5 feet to almost 9 feet. Fourteen steps descend into the cave; the three lowest steps are semicircular. Two bedrock projections extend into the stairway area on either side of the steps. The one on the right as you descend is known as “the tongue.” You can touch it as you descend into the cave. These projections indicate that the original width of the entrance to the cave was much narrower than it is today.

Nearly in the center of the cave’s ceiling is a hole about 3 feet in diameter cutting through the bedrock to the surface of es-Sakhra. The distance from the ceiling of the cave to the surface of es-Sakhra is, at this point, 5 feet 7 inches; there are no signs of rope marks at the edges of the top of the hole as would be the case with the wellhead of a cistern.

The hole is first mentioned in a record of a visit to the Dome of the Rock by Ali of Herat in 1173,12 15 years before it was taken by Saladin. As the hole is never mentioned in earlier sources, it appears very probable that it was cut by the Crusaders. We know that the Crusaders called this cave the Holy of Holies and venerated it as the site of the annunciation of John the Baptist. As related in Luke 1:5–25, John’s father, Zechariah, was a priest; while officiating in the Temple, Zechariah received a visitation from the angel Gabriel, who announced to him that, although both Zechariah and his wife Elizabeth were advanced in years, she would bear his son. Not long thereafter Elizabeth conceived and bore a son who would grow up to be John the Baptist. If the cave was typical of such shrines in Crusader times, visitors would have lighted candles, so a ventilation system was imperative. The Crusaders may have cut this hole to achieve this purpose. In short, the hole in the ceiling of the cave is simply a Crusader chimney.

One of the first clues I found relating to the wall of the original Holy of Holies is on the surface of es-Sakhra adjacent to this Crusader chimney. Two flat, slightly depressed, rectangular areas can clearly be discerned west of the hole. The smaller of the two flat areas lies to the immediate west of the hole. The other, located adjacent to the smaller one but further to the west of it, is longer. Each is about 3 feet wide; the shorter one is approximately 5 feet long and the longer about 8 feet long. The shorter one is a few inches lower than the longer one.

Gustaf Dalman had already noticed these flat areas but could not understand their purpose and did not think that the near surroundings indicated their function either.13 He cites Rudolf Kittel, who thought that the lower one, because of its close proximity to the hole, was a receptacle for blood, channeling it into the cave below.

In countless archaeological sites I have seen rock that has been leveled to create even bases for square or rectangular foundation stones of buildings. Without cutting a foundation trench, the stones would have wobbled about, making the building unsafe. The same would be true for the walls of the Temple. In short, these flat areas were very familiar to me as foundation trenches.

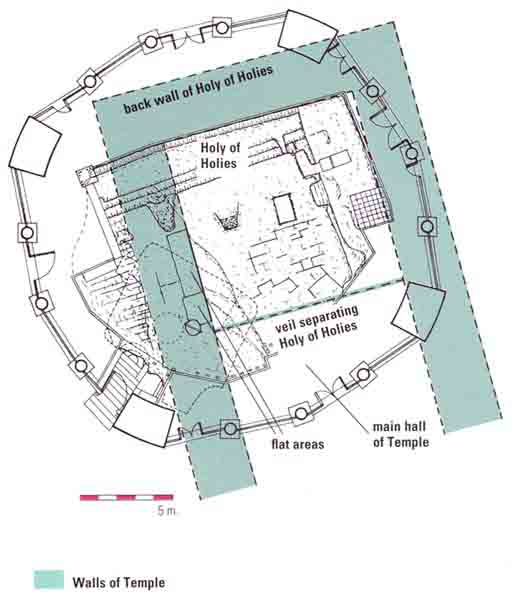

But why would one of the walls of the Temple be built on es-Sakhra? Asking the right question was almost the same as providing the answer. The visible surface of es-Sakhra is approximately 43 feet by 56 feet. This is larger than the Holy of Holies in the Temple, which measured 20 cubits—or 34 feet 6 inches—square. If this was indeed the location of the Holy of Holies, then at least one of its walls must have been built on es-Sakhra. As es-Sakhra is also called the Foundation Stone, it would truly live up to its name if this were so.

If we stand on the southern side of the balustrade enclosing es-Sakhra, we can see additional flat areas south of the two just described, although these additional flat areas are not so well defined. Nevertheless, together with the flat areas to the west of the hole leading down to the cave, they appear to form a foundation trench for a broad wall, which would have run from east to west. The thickness of this wall, based on the measurements of this southern foundation trench, is over 10 feet (3 meters) from north to south. The bedrock to the south then slopes down steeply.

The coincidence between this measurement and the measurement given in Middot 4.7 for the thickness of the walls of the Second Temple—6 cubits, or 10 feet 4 inches—is irresistible. Preserved here on the face of es-Sakhra, despite all the Crusader insensitivity to the Rock, was the imprint of the southern wall of the Holy of Holies.

Now let us look at the western face of es-Sakhra. Standing at the wooden balustrade, we find ourselves facing a natural rock scarp that rises 3 feet 7 inches (1.09 meters) above the pavement. (The bottom of the scarp, below the floor, is difficult to see because it is so close to the balustrade.) This natural rock scarp has many deep grooves running up and down. I counted 27 grooves in the western face of the rock; in the southern part, 8 grooves are identified by the Moslems as fingers of the angel Gabriel, who held down the rock when it wanted to follow Mohammed during his ascent from es-Sakhra to heaven.

Although the north-south line of the rock scarp is slightly broken, the major direction is approximately 3.5 degrees east. This is a very significant number. Those who read my previous article locating the original, square Temple Mount will recall that the first telltale clue was a step at the base of the northwest stairway leading up to the Moslem platform on which the Dome of the Rock is built.14 This step turned out to be part of a wall at the northwest corner of the original Temple Mount that was precisely parallel to the eastern wall of the Temple Mount. Both this step (hereafter “the Step”) and the eastern wall of the Temple Mount are aligned almost identically to the line of the rock scarp on the western face of es-Sakhra—approximately 3.5 degrees east! The line of the rock scarp on the western face of es-Sakhra marks the inner face of the western wall of the Temple—the back wall of the Holy of Holies—perfectly parallel to the western wall of the original Temple Mount (the Step) and the eastern wall of the original Temple Mount. The back wall of the Temple stood at the foot of this natural western scarp, with es-Sakhra on the east.

The longitudinal axis of the Temple was at a right angle to this western wall. As the western scarp is natural—and therefore never changed its direction—there are no grounds to believe that the axis of the First Temple was different from that of the Second Temple.15 Both were oriented in precisely the same west-to-east direction, with the portal on the east, facing the rising sun. Interestingly, the continuation of this axis aligns with the top of the Mount of Olives (across the Kidron Valley), where the red heifer was sacrificed (see Numbers 19). According to Middot 2.4, the high priest who burns the red heifer and stands on the top of the Mount of Olives should be able to look directly into the entrance of the Sanctuary when the blood is sprinkled. This is another confirmation of my location and direction of the Temple.c

We now have two walls of the original Holy of Holies. The distance from the wall we have identified as the southern wall of the Holy of Holies to the northern edge of es-Sakhra is 34 feet 5 inches (10.5 meters). Converted to cubits, the result is startling: The distance is exactly 20 cubits, the Biblically prescribed measurement of each side of the Holy of Holies! Here the northern wall of the Holy of Holies would have been built, exactly at the foot of the northern scarp of es-Sakhra, which was originally cut for that purpose.

We now have three walls of the original Holy of Holies.

There was no wall on the eastern side of the Holy of Holies. It was separated from the main hall (the Heichal, or Holy Place, as distinguished from the Holy of Holies) of the Temple simply by a partition made of olive wood in Solomon’s Temple and by a curtain or veil in Herod’s Temple. Therefore, no signs of a partition would be visible on the sloping surface east of es-Sakhra. Nevertheless, on the plan, we can easily plot the division line between the two chambers of the Sanctuary. The curtain or veil was 20 cubits from the back wall.

It appears that on the east a gentle natural slope or ramp led up to the top of es-Sakhra, which, before the Crusaders’ transformation of it, was much larger, with flat rock filling most of the Holy of Holies. The layers of rock in the ramp can be observed from the northern side of the balustrade as if the layers were in section, as they are in the balk of an archaeological excavation. Near the top of es-Sakhra, the thin rock layers of which the mountain is made up are horizontal; towards the east, however, they dip down to the level of the pavement near the eastern balustrade. It appears that the bedrock continues to slope down in an easterly direction below the pavement. I believe that this slope continues downwards until it reaches the general depth of 3 feet 3 inches below the floor.

While this indicates that the bedrock originally formed a ramp leading to the top of es-Sakhra,16 the slope has been somewhat affected by Crusader quarrying. Many quarry marks on the sloping surface of the eastern part of es-Sakhra are still visible. It is generally agreed that this is the result of the Crusader practice of raising money by selling pieces of the Rock for their weight in gold.

In the Temple of Solomon and in its later reconstructions, the eastern slope would have served as a ramp for the high priest to ascend once a year, on Yom Kippur, to the Holy of Holies.

The upper surface of es-Sakhra is difficult to see from ground level. It is easier to examine by means of photographs taken from high up, under the dome. On the northern side, the top is approximately 10 feet wide; it widens to about 20 feet in the south. The southern part is a little over 4 feet above the floor. The highest point, in the middle, is nearly 6 feet above the floor.

Two depressions are visible in the northern half. The southerly one is what looks to be an artificially cut trapezoid spreading out to the west. In the deepest part, no rock is visible, only small stones and mortar. It has been suggested that this place may be of special importance as the planting place of a tree for Asherah. However, as this depression is located at the very center of the Dome of the Rock, it may have played a role as the central pivot from which the plan of the Dome of the Rock was set out on the ground for its construction.

Just to the north of this trapezoidal depression is a rectangular depression that I believe is of extraordinary significance. My attention was first drawn to this feature on a flight to Israel in the spring of 1994. I remember the moment well—we were flying at 30,000 feet. Having averted my gaze from the in-flight video, I had taken out of my briefcase a large photograph of es-Sakhra.

Using the flat areas on the south of the Rock as a starting point, I had already tentatively traced the walls of the Holy of Holies and needed merely to confirm this on-site. Then suddenly I noticed that in the middle of this square room was a dark rectangle! The first thing that came to mind was, of course, the former location of the Ark of the Covenant, which once stood in the center of the Holy of Holies in Solomon’s Temple. But that surely could not be true, I thought. It must have been something else. Although very excited, I was determined not to be carried away. I needed to investigate this properly, treating es-Sakhra as one of the many archaeological sites I had worked on. I knew that if I were to claim such a function for the rectangular depression without proper investigation I would be dismissed as a sensationalist crank, as has happened to many others who have claimed to have found the Ark of the Covenant or to have identified its former location on the Temple Mount or elsewhere in the world.

I have tried to debunk this theory by thinking of other explanations for this rectangular depression in the center of the Holy of Holies. The only other possibility I have thought of is that it might be a column base for a statue. Early Christian pilgrims to the Temple Mount tell of seeing two statues on the site of the former Temple. Could this depression be the base for one of those statues? But column bases on which statues were erected are always square. This depression was rectangular; it measured 4 feet 4 inches by 2 feet 7 inches. It was also far too small, according to Roman classical proportions, for a Roman column base of any height; and these statues, if they existed here at all (and the sources are not fully reliable), were designed to impress. Furthermore, the Roman temple to Jupiter, which was also mentioned in these sources, would have stood on the highest spot on the Temple Mount, using es-Sakhra as a podium, with the statues either to the west or east of it, not inside it. The result would have been that es-Sakhra was effectively buried and protected during this period.

According to Josephus, the Holy of Holies in Herod’s Temple was completely empty: “In this stood nothing whatever: unapproachable, inviolable, invisible to all, it was called the Holy of Holy.”17 Josephus was apparently unaware of the existence of this most interesting feature.

According to my plan, this depression falls exactly in the center of the Holy of Holies. Converting its dimensions into cubits produces another rather startling fact. It measures exactly 1.5 by 2.5 cubits (2 feet 7 inches by 4 feet 4 inches, or 80 centimeters by 130 centimeters). These are the dimensions of the Ark of the Covenant the Lord told Moses to build in the wilderness (Exodus 25:10), the Ark that was ultimately placed in Solomon’s Temple.

In the end, the conclusion that this unique depression marked the emplacement of the Ark of the Covenant inside the Holy of Holies is inescapable.

The Biblical text contains strong indications that a special “place” was prepared for the Ark of the Covenant within the Holy of Holies. In 1 Kings 8:6, we are told “The priests brought in the Ark of the Covenant of YHWH to its place, in the dvir [oracle, or speaking place] of the Temple” (italics added). Such a sacred object could not be left to wobble about on the uneven surface of the Rock but would need a stable base on which to stand. The cutting of a flat basin such as this was the obvious solution.

In 1 Kings 8:20–21, Solomon declares that he has “built the Temple for the name of YHWH God of Israel. And I have set there a place for the Ark in which is the covenant of YHWH that he made with our fathers when he brought them out of the land of Egypt” (italics added). The Hebrew verb that is translated here as “set” (

One thing still mystified me about this depression—its orientation, with the short side facing the partition separating the Holy of Holies from the main hall of the Temple. Most depictions of this scene show the Ark standing in the Tabernacle or in the Temple with its long side facing the partition. It is now clear that it stood with the short side facing the partition. A little thought reveals that this was the only way it could have stood. Otherwise, the priests would not have been able to take out the staves or poles by which it was carried. 1 Kings 8:8 explains that “the staves [also translated as “poles”] were so long that the ends of the staves were seen out in the Holy Place [the main hall of the sanctuary].” According to the Talmud (Yoma 54a), the staves were 10 cubits long. The Holy of Holies was only 20 cubits square. If the priests carrying the staves had turned the ark so that the long side faced the partition, they would not have been able to remove the staves after placing the ark in the center of the Holy of Holies. The only way to remove the staves was by keeping the short side facing the partition that separated the Holy of Holies from the Holy Place.

When Herod rebuilt the Second Temple, he raised the entire structure by building it on a foundation 6 cubits high. Instead of via a ramp leading up to es-Sakhra, the level of the Temple floor was reached by a 12-stepped staircase outside the Temple, in front of the porch, as described in Middot 3.6. The ramp was completely buried below the pavement of the new Temple floor. Only the very top of es-Sakhra remained visible inside the Holy of Holies. This new Temple floor was a little lower than the top of es-Sakhra, which was still the floor of the Holy of Holies. This explains a passage in the Mishnah (Yoma 5.2) describing the activities in the Temple on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) in the Second Temple period, that is, “after the Ark had been taken away”: A stone in the otherwise empty Holy of Holies is referred to as the Foundation Stone (Even ha-Shetiyah), which “was higher than the ground by three fingerbreadths.”

The Mishnah describes in some detail how on Yom Kippur the incense was ladled into a fire-pan by the high priest, how it was heaped upon the coals and how the fire-pan was placed on the Foundation Stone, the Even ha-Shetiyah: “On this [the Foundation Stone] he [the high priest] used [before the Roman destruction of the Temple] to put [the fire-pan].”

I believe that, when the Second Temple still stood, the High Priest on Yom Kippur would place his censer or fire-pan in this depression—the same place where, during the First Temple period, the Ark of the Covenant stood.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Some proposals would have put the altar on es-Sakhra, but then es-Sakhra would have disappeared completely below it, as es-Sakhra is smaller than the altar. According to Middot 3.1, the altar was 32 cubits (55 feet, or 16.8 meters) square. Another problem with placing the altar over es-Sakhra is that the well-known cave that lies below es-Sakhra, which was supposed to have drained off the blood to the Kidron Valley, would be in the wrong place, as, according to Middot 3.2, this original drain was located at the southwest corner of the altar, while the cave is on the southeast corner.

See Leen Ritmeyer, “Locating the Original Temple Mount,” BAR 18:02.

Endnotes

Leen Ritmeyer, “Locating the Original Temple Mount,” BAR 18:02.

Ephraim Stern, ed., The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), vol. 2, p. 718.

The details of the research and a comprehensive overview of how the Temple Mount developed is due to be published soon in book form by the Biblical Archaeology Society.

Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine During the Years 1873–1874 (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1899), vol. 1, pp. 216–217.

I would like to thank Joseph G. Hurley, Esq., and his wife Davia Solomon, Esq., for their continued support in the form of a second generous grant through the Biblical Archaeology Society for this work. A travel grant from the Rothschild Foundation made it possible for my family and me to spend considerable time in Jerusalem during the spring and summer of 1994 while I did the post-doctoral research on which this article is based, under the supervision of Professor Gideon Foerster of the Hebrew University.

Gustaf Dalman, Neue Petra-Forschungen und der heilige Felsen von Jerusalem, chap. 4, “Der heilige Felsen von Jerusalem,” J.C. Hinrich (Leipzig, 1912). See also Hans Schmidt, Der heilige Fels in Jerusalem (Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1933).

Fulcher of Chartres, A History of the Expedition to Jerusalem, 1095–1127, trans. F.R. Ryan (Knoxville: Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1969) I, xxxi, 5–10.

F. Gabrieli, Arab Historians of the Crusades (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1969), pp. 168–171.

Retired Hebrew University physics professor Asher Kaufman shows two different orientations for the First and Second Temples, although there is no historical proof that this was so.

His orientation of the Second Temple is based on the assumption that the Temple was trapezoidal in shape. As evidence, he relies on a glass fragment of the Byzantine period that shows a painting of the Temple with surrounding walls. These walls are drawn in perspective, a normal artistic procedure, and the resulting tapering shape cannot therefore be used as archaeological evidence that the Temple was trapezoidal. He then tries to match this idea up with some very small bedrock cuts and the directions of water cisterns to prove his point.

His orientation of the First Temple is derived from another small bedrock cut to the north of the platform of the Dome of the Rock (see “Where the Ancient Temple of Jerusalem Stood,” BAR 09:02). It is true that these bedrock cuts were probably part of the foundation trenches of a building, but they are insufficient in themselves to prove that they were part of the Temple. (I believe that they may have had something to do with the foundations of the Towers of Hananeel and Mea, which were later replaced by the Baris Fortress.) He also claims that his “Find 14” was a “crypt supporting the northeastern angle of the Court of Priests and part of the Outer Court” (p. 56). Warren, who discovered this vault in Cistern 29, wrote, “The vault itself seems clearly to be Arab work not earlier than the 13th century” (with Claude R. Conder, The Survey of Western Palestine, Jerusalem [London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1884], p. 224). To incorporate a medieval structure into the First Temple is archaeologically impossible, to say the least.

Kaufman’s interpretation of these remains hinges, of course, on a partially broken paving slab below the so-called Dome of the Spirits, which he claims was the Foundation Stone. However, the shape of this stone, with a rectangular projection on its eastern side, makes it abundantly clear that it is indeed a paving slab. The purpose of this rectangular projection is to enable a smaller paving slab to be laid next to it. Kaufman’s theory also contradicts Josephus’s historical record that the Temple stood on the summit of the mountain. The bedrock below Kaufman’s paving slab, which, incidentally, is smaller than other paving slabs found in front of the Double and Triple Gates, is about 16 feet lower than es-Sakhra according to Warren’s plans! The slab is also far too small for a foundation of the Temple, as the Holy of Holies alone was about 10 times larger than this stone.

Additionally, it is archaeologically unsound to use the orientation of cisterns to prove the direction of a building above. Cisterns are usually round or cut at right angles to the bedrock formation, which is not necessarily the direction of the building above.

The opinion of the archaeological community as to Kaufman’s theory is summed up in Stern, New Encyclopedia, vol. 2, p. 743: “An attempt by A. Kaufman to ‘shift’ the location of the Temple slightly to the north of this traditional site [of the Dome of the Rock], relying on unclear archaeological remains he ascribes to the Second Temple period and on other evidence, lacks concrete proof.”

This is confirmed by Clermont-Ganneau’s other observations in the northern part of the Dome of the Rock, where he found bedrock in general a meter below the floor of the Dome of the Rock. In 1959 Bellarmino Bagatti (Recherches sur le site du Temple de Jerusalem (Ier–VIIe siecle) [Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 1979], pp. 28–29) noticed bedrock at several places below the floor during repair operations conducted at that time.