Yigael Yadin’s magnificent edition of the Temple Scroll1—the latest-to-be-published and the longest of all the Dead Sea Scrolls—has been available to scholars in Hebrew for over four years and last year became available in a three-volume English edition. (See “The Temple Scroll—The Longest and Most Recently Discovered Dead Sea Scroll,” in this issue, by Yigael Yadin .)

The Temple Scroll came into Yadin’s hands in 1967. His edition is a remarkable scholarly achievement, especially considering his other duties, inter alia, as Israel’s Deputy Prime Minister. Such an achievement is especially noteworthy in comparison with the records of other scholars, some of whom, without the excuse of such duties, have now withheld from the public Dead Sea Scroll materials assigned to them by an international committee more than 30 years ago.

The Temple Scroll as preserved begins with the Deuteronomic commands (7:5ff.) to obliterate all Canaanite places of worship and to worship Yahweh alone. Then, says the scroll, when Yahweh gives you peace, you are to build him a temple. The scroll then describes this temple at some length; hence the name Temple Scroll. The description of the temple seems to begin with the ark and then moves outward, though the columns of the scroll in which the description appears are so fragmentary that it is difficult to be sure. After describing the table for the shew bread, the menorah and what appears to be an altar for incense, the scroll turns to the altar for sacrifices. Then the various sacrifices and the rules pertaining to them are set forth in elaborate detail—first the daily burnt offering, and then the special sacrifices for Sabbaths, new moons, and festivals.

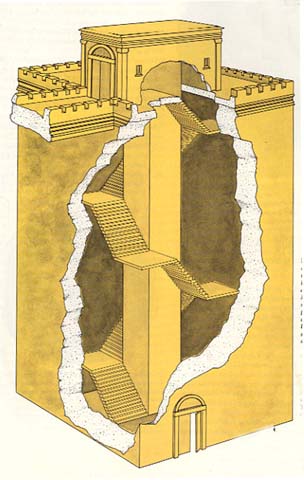

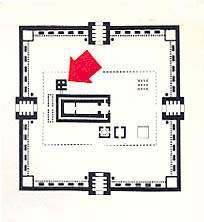

The text then suggests that a second temple will be built by Yahweh himself after the day of blessing. From this, however, the text quickly returns to a description of the temple to be built by the Essenes when Yahweh gives them peace. The text is broken and somewhat fragmentary at this point, but the first relatively coherent passage describes an unusual structure adjacent to the temple: a freestanding gilded staircase!

The staircase is to be built around a square pillar and is to ascend in an angular spiral around each side of the pillar. The staircase is to be enclosed on the outside by a wall four cubits (roughly six feet) thick, thereby forming a staircase tower. The height of the staircase and the enclosing tower is to be the same as that of the temple itself. And this entire structure is to be plated with gold. Here is the text from the Temple Scroll itself (column 30):

“And you shall make … a staircase … in the temple you are to build … And you shall make the staircase tower [the mesibah] north of the cella [heikhal], a square structure 20 cubits from [outer] corner to corner for [all] its four corners, and seven cubits distant from the cella at its northwest [end]. And you shall make the thickness of its wall four cubits [and its height 40 cubits], as [that of] the cella. And its inside [dimensions] from corner to corner [shall be] 12 [cubits]. And inside there shall be a square pillar in the middle of it, four cubits on each side. [And the structure] which surrounds [the pillar shall be] an ascending staircase [to the roof level of the temple.]”

Unfortunately, the next nine lines have been wholly lost and of the five following after them we have only terminal fragments. The text then goes on:

“And on the top of [this] structure [you shall make a gate] opening towards the roof of the cella and a walk made from this gate to the entrance [of the roof of] the cella so that one can go by it to the top of the cella. All this staircase tower you shall plate with gold, its walls and its gates and its roof, inside and out, and its column and its stairs. And you shall do as I tell you in all [details].”

The sole apparent function of this staircase tower with its gate and walk was to give access to the roof of the temple.

A number of other temple staircases are referred to in the Bible and in the Mishnah (an early compilation of Jewish law), but they were built around the walls of the temple itself and were thus quite different architecturally. Other staircases are referred to in the Dead Sea Scrolls, but these were built in the corners of walls.

It makes sense to build a staircase along an existing wall, whether a city wall or a building wall, and even more sense to build a spiral staircase in the corner of the structure, utilizing the two walls—this is one of the least expensive ways of building a stairway. But a staircase located outside a building as a completely separate structure is the most expensive possible form of staircase. When, besides this, it is to be gold-plated, inside and out, it becomes conspicuous both as a budgetary item and as a historical problem.

Since the only apparent function of this gold-plated staircase was to give access to the roof of the temple, we should suppose that some ritual of great importance was to be conducted on that roof. Both in the Bible and in the Temple Scroll, gold is characteristic of the areas and ritual objects most closely connected with the deity: the Holy of Holies, the Ark, the Holy Place, the altar of incense, the menorah, and the table for shew bread.

Both artifactual and literary evidence suggest that the temple rooftop ritual involved sun worship. Strabo, the Greek geographer, tells us that the Nabataeans worshipped the sun and built altars on the roofs of their houses, on which libations were poured and incense burned.2 Staircase towers occur in Nabataean temples from the first century B.C. and were common in Nabataean private houses from the first and second centuries A.D.3 Many ancient coins show altars on temple roofs.4

Moreover, in a much-debated passage, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus seems to suggest that the Essenes worshipped the sun. The passage from Josephus reads as follows:

“[The Essenes are] peculiarly reverent towards the divinity [to theion] for, before the sun rises, they say nothing of profane things, but [only] certain ancestral prayers to him, as beseeching [him] to rise” (Jewish Wars, 2.128).

In another passage, Josephus refers to the well-known Essene custom of covering themselves while moving their bowels. According to him, they do so “in order not to insult the rays of the god” (Jewish Wars, 2.148f.). For the same reason, no doubt, they buried their excrement.5 The Biblical commandment that they are supposed to have been observing is Deuteronomy 23:12–14, which concludes: “Yahweh your God goes about in the midst of your camp … so your camp is to be holy, in order that he should not see any shameful thing among you and leave you.” Thus Josephus’s report that the Essenes take these precautions to avoid offense to the “rays of the god” seems to derive from an equation of the sun god with Yahweh, present in his rays.

Long before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars studying the passages from Josephus debated whether or not the Essenes worshipped the sun. Some suggested that the Essenes did not worship the sun but treated it as a symbol. Others suggested that the prayer the Essenes offered before sunrise “beseeching [the divinity] to rise” was simply the Shema, the traditional Jewish prayer said at the coming of daylight. Neither of these explanations carries conviction, the first because it does not match Josephus’s text and the second because if the prayer offered had been simply the Shema, it would not have been worthy of note—and Josephus himself refers to the predawn Essene prayer “beseeching [the divinity] to rise” as a “peculiar” practice.

Because these explanations were unsatisfactory, still other scholars suggested that the Essenes did indeed worship the sun but that they did so under Greek—specifically Neo-Pythagorean—influence. This suggestion was more safe than informative because almost nothing is known about Neo-Pythagorean sun worship in the Hellenistic period.

Because of the prestige of the unknown, this explanation was widely accepted before the discovery of the Dead Sea documents, which demonstrated that the Essenes were meticulous in their observance of the Mosaic Law. They were, indeed, a clique of sanctimonious fanatics who became sectarians primarily as a result of their severe interpretations of the Mosaic Law. Other factors—over-confidence in their own interpretations, contempt for those who did not agree with them, pretensions to hobnob with angels, consequent revelations both prophetic and legal, and ultimate remodeling even of the law to suit their own prejudices—all these shaped their doctrines, but the essence of their society can be found in an unusually strict adherence to an unusually severe set of legal interpretations, especially of Sabbath and purity law and possibly of the calendar.

This is not to say that all of Essene doctrine can be found in the Pentateuch. On the contrary, the Essenes often extended and amplified Pentateuchal law: Where the Pentateuch provides for temple vessels, the Temple Scroll provides for a special structure to house them; where the Pentateuch provides for a festival at the offering of the first loaves from the new grain, the Temple Scroll adds festivals for the offering of the new wine, the new oil, and so on. But these are understandable extrapolations from the earlier text.

The golden staircase, however, suggesting a roof ritual involving sun worship is toto caelo different from any extrapolation of Pentateuchal teaching or practice—it is a radical innovation, not explained by anything in the Pentateuch. If meticulous observance of the Mosaic Law means anything, it surely includes a prohibition of the worship of any god save Yahweh.

What then is the answer to the puzzle? How did the Essenes become sun worshippers?

The source of this influence need not be sought in Neo-Pythagoreanism or even in Greece. The fact is that sun worship was pervasive within the confines of the Near East itself. Sun worship was a prominent element in Egyptian religion. Indeed, the Jews from the fifth-century B.C. colony at Elephantine in the Upper Nile had a text of the sayings of Ahiqar in which the great god of wisdom and justice is Shamash (the Sun).6 During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, sun worship became increasingly prominent in Transjordan and Syria.7

In Palestine itself, sun worship was well established before the Israelite conquest. The names of three towns referred to in the Bible clearly reflect this: Beth Shemesh (“Temple [House] of the Sun”), Ein Shemesh (“Spring of the Sun”) and Ir Shemesh (“City of the Sun”). Invaders devoted to Yahweh alone are unlikely to have given these names to these towns.

One of the heroes of early Israelite legend was Samson (Shimshon, from shemesh, approximately “Sunman”), whose adventures have been patriotically retold in Judges 13–16.

The Israelites shared the common ancient belief that the sun, moon and stars were living beings. A Yahwist theologian declared that the sun had been created “to rule over the day” (Genesis 1:16; Psalm 136:8), and Israelite poets described the sun as a bridegroom coming out of the bedchamber (Psalm 19:5)—hardly an apt comparison; the sun in Palestine rarely appears exhausted.

The sun and moon were called on to praise Yahweh (Psalm 148:3; Daniel 3:62 in the Septuagint), and the sun was cited as an example of obedience (Psalm 104:19). He knows when he ought to rise and rises accordingly.

The sun was also the great witness. When the Israelites worshipped the Baal of Peor, “Yahweh said to Moses, ‘Take all the leaders of the people and impale them to Yahweh before the Sun’” (Numbers 25:4). When David sinned with Bathsheha, the prophet Nathan told him, “Thus saith Yahweh … ‘I shall take your wives before your eyes and give them to your companion, and he shall lie with your wives before the eyes of this sun, for you acted secretly, but I shall do this thing before all Israel and before the sun’” (2 Samuel 12:11–12).

It is thus not surprising that many Israelites, like their neighbors, worshipped the sun and commonly did so on the roofs of their houses.

The prophets often complain of Israelite sun worship (Jeremiah 8:2; Jeremiah 19:13; Zephaniah 1:5). Sometimes this sun worship occurs on the roof: “I will wipe out … those who bow down upon the housetops to worship the host of heaven” (Zephaniah 1:4–5; cf. Jeremiah 19:13). Yahwist historians also report sun worship by Manasseh; it is said that he “prostrated himself before all the host of heaven and worshipped them” (2 Kings 21:3). Legal passages warn against sun worship as a forbidden practice (Deuteronomy 4:19; Deuteronomy 17:3).

And the author of Job, to prove the hero’s devotion to Yahweh alone, makes him boast that he never kissed his hand to the sun (Job 31:27). Evidently ordinary people did.

Sun worship is also attested on Palestinian seals of the monarchic period. For example, Nahman Avigad has published four seals from the pre-exilic period, each engraved with a flying sun globe/scarab. In one, the scarab is even adored by two worshippers.8 And such worship was not only private; altars to the sun, moon and stars stood in both courts of the Jerusalem Temple (2 Kings 21:5) and on its roof (2 Kings 23:12), and a chariot and horses given to the sun by the kings of Judah were brought into the Temple (2 Kings 23:11). When Ezekiel envisioned the Jerusalem Temple just before its destruction, he saw in the innermost court “between the cella and the altar, about 25 men, their backsides to the Temple of Yahweh and their faces to the east; and they were prostrating themselves towards the east, to the sun” (Ezekiel 8:16). Only priests should have had access to this area. The participation of priests of Yahweh in sun worship raises a question as to the original meaning of Biblical passages in which Yahweh may he spoken of as the sun. For example, in Malachi 4:2, Yahweh is prophesying the events of the end: “And the righteous sun will rise on you who fear my name, and healing [will come] in his wings.” Everyone knew the sun had wings; the seals regularly showed them.

Evidence of sun worship dating to after the fall of Jerusalem is found all over Palestine, Transjordan and Syria. Much of this evidence comes from the Roman period, typically on coins. This numismatic evidence is only discovered occasionally, but it is supported by Jewish and Christian literary sources as well. For example, the Mishnah contains a ruling that anyone who finds an artifact bearing a representation of the sun, the moon, or a serpent must throw it into the Dead Sea (Mishnah, Avodah Zarah 3:3, etc.). The obvious reason for this ruling is that these objects were commonly worshipped. Again, oaths by the sun were so common and so much used, even by Jews, that rabbinic law finally permitted them, provided the man who swore had the creator of the sun in mind.9

Given the popularity of sun worship in Palestine, we can assume that the Essene practice sprang from local soil. But we are still left with the question as to why the Essenes adopted sun worship, even though it was and had been so prevalent in Palestine for over 2,000 years. After all, though sun worship is frequently referred to in the Bible, it is always condemned and in several passages specifically prohibited. Indeed, the Temple Scroll itself incorporates Deuteronomic passages prohibiting the erection of asherot, massebot, and the like (columns 51.19–52.3) and specifically forbids the worship of the sun, moon and stars (columns 55.15–21).

How then could the Essenes have said prayers to the sun, much less have planned a gold-plated staircase for a splendid approach to such worship?

No doubt they could easily have devised some exegesis to justify their sun worship and even to base the practice on scripture. Dead Sea Scrolls that interpret scripture (the so-called pesharim) are full of absurd Essene exegesis. Qumran legal documents, including the Temple Scroll, swarm with rulings that more or less openly contradict the “plain sense” of Pentateuchal prescriptions. Both the rabbis and the early Christians were able to interpret the Law in almost any way that suited their purposes. The Babylonian Talmud preserves this passage: “Rate Judah said in the name of Rab: ‘No one can be seated in the Sanhedrin unless he knows how to prove from Scripture that a reptile is clean’” (Sanhedrin 17a, end). A reptile, of course, is the most unclean of animals. The Essenes were doubtless as skilled as the rabbis of their time in pretentious misinterpretation of the Law.

Since the particular Essene exegesis permitting sun worship has not been preserved, we can only conjecture what it might have been. Perhaps the Essenes distinguished between “worshipping as a god” and “reverencing and invoking as a supernatural power, but not a god.” The problem could be solved easily in this way. Similar distinctions can be found in the history of Christian veneration of the saints and of Mary (Compare the rabbinic rulings cited by Saul Lieberman.)

But why did the Essenes want to “reverence” the sun ritually? No certain answer can be given to this question. But an answer may be indicated by a passage from Deuteronomy—a passage that seems to refer to the exile and therefore to come from the post-exilic period. This dating makes it more relevant to Essene history. In this passage Moses tells the Israelites:

“Watch out for yourselves. You saw no image whatever on the day when Yahweh spoke to you at Horeb from the fire. [Take care, therefore,] lest you … make any idol … and lest you look up to the sky and see the sun, moon and stars … and bow down to them and serve them. For Yahweh your God gave them [the sun, moon and stars] to all the peoples under heaven [as objects for worship], but Yahweh took you … to be his hereditary people … Take care, therefore, lest you forget the covenant of Yahweh … and make yourselves an idol, an image of anything … For Yahweh, your God, he is a devouring fire, a jealous God.”

(Deuteronomy 4:15–24)

Yahweh is thus “a devouring fire.” The nearest thing to a visible representation of a god of fire is the sun. And it is a simple step from “visible representation” to “visible representative.”

Moreover, this passage from Deuteronomy all but says that the celestial bodies are supernatural beings given by Yahweh to the gentiles as the proper objects for their worship. Hence it would be easy to conclude that they should be reverenced (though not “worshipped”) by Jews. The many synagogue floor mosaics of the fourth century A.D. and later that have at their centers the sun driving his chariot are evidence that this conclusion was later drawn in Palestine.10 Not only reverence but actual worship is proved by the passages in Sefer harazim giving directions for the prayers and rites to be used in the worship.11

As self-styled “children of light,” the Qumran sectarians had a special interest in the luminaries, particularly the sun. This is shown not only by their prayers for sunrise but also by their abandonment of the lunar calendar prescribed by the Bible in favor of one represented as solar—one of their more important departures from Pentateuchal law. Enoch and Jubilees, which set forth this solar calendar, emphasize the role of the sun (versus the moon) as ruler of the year.

The Essene worship, or at least “reverence,” for the sun should thus come as no surprise.

(For further details, see Morton Smith, “Helios in Palestine,” Harry M. Orlinsky Volume [Eretz Israel 16 (1982)], pp. 199–214.)

MLA Citation

Endnotes

Yigael Yadin, The Temple Scroll (Jerusalem, 1977) in three volumes and a fascicle of supplementary plates. Also published in an English edition (1983) under the same title.

Avraham Negev, “The Staircase-Tower in Nabataean Architecture,” Revue Biblique 80 (1973), pp. 364–382.

Joseph Lightfoot in St. Paul’s Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon, 2nd ed. (London, 1879). Note 2 on p. 87 shows by numerous classical parallels that “the god” here means “the sun god.”

Arthur Cowley, Aramaic Papyri of the Fifth Century B.C. (Oxford University Press, 1923), pp. 204–248.

For the archaeological evidence for Syria, Transjordan and Palestine see Henri Seyrig, “Antiquités Syriennes 95, Le Culte du Soleil en Syrie à l’époque Romaine,” Syria 48 (1971), pp. 337–373. Reference has already been made to Nabataean sun worship on the roofs of houses.

Nahman Avigad, “Hotem,” Encyclopaedia Biblica III (1958), pp. 68–86 and plate 3. Further examples may be found in Stanley Cook, The Religion of Ancient Palestine in the Light of Archaeology (London, 1930), pp. 48–52 and plates VI–IX, XII, XIII, XV.

See Saul Lieberman, Hellenism in Jewish Palestine (Texts and Studies of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America 18, 2nd ed. [New York, 1962]), pp. 214–15, supplementing the evidence already given in his Greek in Jewish Palestine (New York, 1942), pp. 137–38.

Mordecai Margalioth, ed., Sefer harazim, (Jerusalem, 1966). The directions for sun worship are in the account of the fourth heaven. Margalioth reconstructed the book mainly from fragments found in the genizah of the old synagogue of Cairo. The original was probably about contemporary with the Palestinian synagogue mosaics referred to in the previous endnote.