034

036

Piero della Francesca: The Legend of the True Cross in the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo

Edited by Anna Maria Maetzke and Carlo Bertelli

(Milan, Italy: Skira, 2000; distributed in the U.S. by Rizzoli [www.rizzoliusa.com]) 340 pages, 230 color and 30 b&w illus., $75.00 (hardback)

034

Helena’s discovery of the true cross is only one stage in an elaborate history of the cross that developed in medieval Europe. The complicated story conflates Old Testament and New, ancient history and myth. It begins with a sapling from Eden, from which the cross will eventually be carved; it ends with a Byzantine battle against the Persians. The cast of characters includes Adam, Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, the Roman emperors Constantine and Heraclius, angels and Jewish wise men.

The most thorough account of the cross’s history is in the Golden Legend, a collection of apocryphal tales and lives of the saints written about 1260 in Genoa, Italy, by the Dominican Jacobus de Voragine. The most beautiful retelling appears not in manuscript form, however, but in fresco. Sometime in the mid-15th century, the Italian artist Piero della Francesca (c. 1417–1492) painted the full history of the cross on the walls (photo, above) behind the main altar of the Church of San Francesco, in Arezzo, Italy (southeast of Florence).

Since Piero first painted the scenes, they have suffered from earthquakes, lightning, climate change, botched restoration jobs and pot shots from French soldiers quartered in the church during the Napoleonic occupation.

Now, a 15-year, $5 million restoration effort has repaired cracks and removed centuries of soot and grime to reveal the brilliant colors beneath. Piero’s filmy white clouds float easily in clear skies; in the night scenes, the stars twinkle once more. The results are documented in 230 glorious color photos (including numerous close details) in Piero della Francesca: The Legend of the True Cross in the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo, edited by Anna Maria Maetzke and Carlo Bertelli.

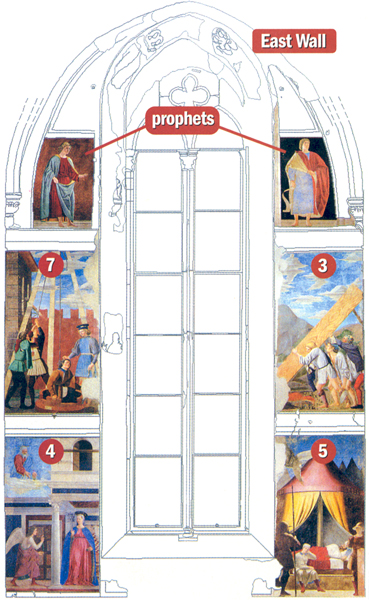

Piero’s frescoes retell the story with larger-than-life figures arranged in three registers on the three walls of the rectangular apse. The tale begins in the top register on the southern wall, to the right of the altar.

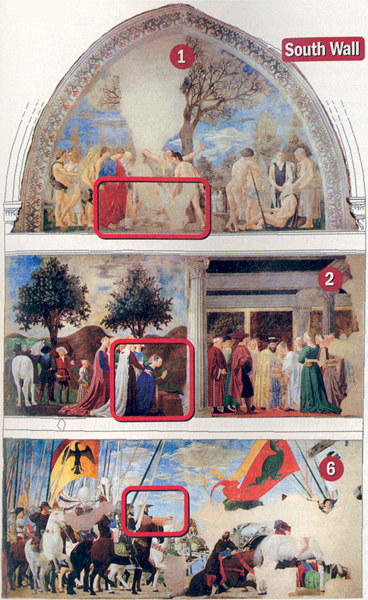

Adam is dying (fresco 1). He first appears seated on the ground at far right (this panel, unlike all the others, reads from right to left). Frail and tired, Adam is showing his age (930 years, according to 036Genesis 5:5). Yet, according to the Golden Legend, Adam is reluctant to give up the spirit. He sends his youngest son Seth back to Eden to obtain restorative oils. In the distance, we see Seth conferring with the archangel Michael at the Garden’s gate. The angel refuses Adam’s last request, however, informing Seth that his father cannot be raised from the dead for at least five thousand years; that is, until Jesus is crucified and resurrected. Only then will Adam be able to join Jesus in heaven. To appease Adam and all his descendants (all mankind), the angel sends Seth home with a sapling from a tree. He instructs Seth to place the sapling in Adam’s mouth. The tree that sprouts from Adam will bring salvation, the angel promises, in that it will provide the wood for Jesus’ cross.

The tree growing from Adam’s mouth is a strange and mysterious image (outlined in fresco 1 in the plan and detail above). This detail is absent from Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend (he mentions a cedar shoot planted on Adam’s grave, but not in his mouth). But de Voragine, who often lists and questions the sources on which he draws, also mentions “an apocryphal history of the Greeks” that claims the sapling came not from just any tree in Eden, but from the Tree of Knowledge. Perhaps Piero is “quoting” from this now-lost apocryphal tale.

Remember, Adam sinned by eating the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. His punishment: toil, suffering and death (Genesis 3:14–19). For Christians, Adam’s sin introduced mortality to humankind; Jesus’ death on the cross restored the promise of immortality. Adam’s sin thus made immortality through Jesus 037a possibility. It is in some ways strangely appropriate to conflate the tree that produced the instrument of sin—the Tree of Knowledge—with the tree that produced the instrument of redemption—the tree of the cross. Perhaps the same logic led Piero to depict the very mouth that ingested the forbidden fruit as nurturing the tree that would be used to bring immortality.

The story continues in the panel below (fresco 2). It is several hundred years later. Solomon is king, and the Queen of Sheba is coming to visit. Her entourage (including several beautiful maids, one dwarf and four horses) appears at left. According to the Golden Legend (but not shown here), the sapling from Eden has already grown into a full tree and been cut down by Solomon’s builders, who planned to use it in his Jerusalem Temple. The wood behaved peculiarly, however; no matter where the builders tried to place the plank, it was too long or too short, too narrow or too wide. So they tossed it into a pond, where it served as a makeshift bridge.

In the fresco, the Queen of Sheba, dressed in royal blue, has just arrived at the bridge. She has a vision (not shown) of Jesus crucified on the wood, and she drops to her knees (center of fresco 2, detail shown above). The queen then continues on to Solomon’s grand columned palace (at right) where she (now dressed in white) bows before the king (with black hat) and tells him of her vision. According to the Golden Legend, she warns Solomon that the man who will be crucified on this wood will bring down “the kingdom of the Jews.”

Solomon instructs his men to bury the wood “in the bowels of the earth” (fresco 3, on the eastern wall) where it remains for 1,000 years, until the time of Jesus, when the area is flooded with water and the wood floats to the surface.

Chronologically, the next scene is the Annunciation (fresco 4), in which the angel Gabriel informs Mary that she will give birth to God’s son. God himself watches the scene unfold from a cloud floating above Mary’s house. With his hands, he scatters gold dust—divine seed?—on Mary. The Annunciation is not incorporated in the Golden Legend’s account of the true cross; nor is it included in earlier Italian paintings of the story of the true cross. Piero probably added it at the behest of the Franciscan monks who invited him to paint their chapel. By placing the fresco out of sequence, on another wall, Piero makes clear that this is not really part of his story.

The legend of the true cross picks up again with Constantine’s dream (fresco 5). It is the night before the Battle at the Milvian Bridge, and the emperor-to-be is camping out near the battlefield. Three guards protect 038him as he sleeps. But none notice the descending angel (at upper left) who casts a supernatural light on the tent. The angel bears a delicate wooden cross. In the Golden Legend (and the writings of the fourth-century church historian Eusebius), an angel holding a cross appears to Constantine in a vision and tells him, “In hoc signo vinces” (“With this sign, you will conquer”).

In the next panel (fresco 6), Constantine leads his men into battle, holding before him the angel’s delicate cross (detail, above). (The cross appears at the center of all three frescoes on this wall, in the form of a battle standard, a bridge and a sapling.) The troops of Maxentius, Constantine’s rival, flee to the right. (This is difficult to see in this badly damaged panel, but note that every extant human or horse leg is headed to the right.) Piero shows the cross as small and insignificant, as if to remind viewers that it is not the object itself, but the divine power behind it, that will lead Constantine to victory.

The story now jumps to the middle register of the eastern and northern walls (frescoes 7 and 8). Constantine’s mother Helena has traveled to Jerusalem in search of the true cross. In fresco 8 (shown below) she appears first at far left, wearing a pointed cap.

This is the ugliest part of the tale. According to the Golden Legend (and the earlier, influential Judas Kyriakos legend, a fifth-century account of Helena’s journey), when Helena arrived, she convened a meeting of the local Jewish wise men (not shown) and asked them to reveal where Jesus was buried. Only one knew, Judas Kyriakos, but he feared the discovery of the cross would cause Christianity to eclipse Judaism and he refused to tell. Helena threatened his life: “I swear by the Crucified that I will starve you to death unless you tell me the truth!” She then threw him into a dry well, with no food or water, for seven days, until he finally agreed to show Helena the site. The anti-Semitism of the tale may account for its popularity in medieval Europe.

In Piero’s painting (fresco 7), a Jew (identified by his flat hat, like Solomon’s in fresco 2, and the fake Hebrew inscription on his hatband) holds Judas by the hair while two of Helena’s men use a pulley to lower him into the well.

Once Judas points out the site, Helena makes quick work of digging up the cross (at left in fresco 8). She is so successful that she finds not one but three crosses—those of Jesus and the two thieves crucified on either side of him—and she is unsure how to identify one as Jesus’. A sick man happens to be carried by on a litter (at right in fresco 8), and she instructs her men to touch the man with the crosses. When he is miraculously cured, she knows the cross touching him must have belonged to Jesus.

As a backdrop to the scene, Piero includes the Temple of Venus, which the fourth-century church historian Eusebius says was constructed on Golgotha by Emperor Hadrian in the mid-second century A.D. According to Eusebius, the pagan temple was torn down in Constantine’s day and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built on the spot.

The last two scenes (frescoes 9 and 10) are set 300 years later. The Persian king Chosroës has invaded Syria, Palestine and Egypt, and stolen the relics of the cross from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The Byzantine emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641) rushes into battle (fresco 9), with the imperial standard, depicting an eagle, waving above him. Compared with Constantine’s easy 039victory at the Milvian Bridge (fresco 6), this is a tumultuous fight with clashing swords and spilt blood. But of course Heraclius prevails. At far right (detail above), he sentences King Chosroës (in blue, kneeling) to death. Piero often used the same face for different characters in his paintings: Surprisingly, the enemy Chosroës looks just like God in the Annunciation (fresco 4).

Heraclius is now free to return the true cross to Jerusalem. According to the Golden Legend, he decided to celebrate his success with a grand victory parade into Jerusalem, but the stones of the city gate fell down, blocking his horse’s path. An angel appeared and suggested that Heraclius show greater restraint: “When the king of heaven passed through this gate to suffer death, there was no royal pomp. He rode a lowly ass, to leave an example of humility to his worshipers.” Heraclius gets the point. He gets off his high horse, removes his regalia and his boots, and humbly walks into Jerusalem carrying the cross (fresco 10), where he is greeted by the city elders. The story ends, with the cross back in Jerusalem.

For all its detail, Piero’s account of the true cross has one gaping hole. The most important event in the history of the cross is absent: the crucifixion. The story jumps from the Annunciation (fresco 4) to Constantine’s dream (fresco 5).

Piero had good reason, however. As mentioned earlier, Piero’s paintings were on the apse walls directly behind the main altar of the church of San Francesco. In Piero’s day, a massive 13th-century crucifix—a cross bearing the body of Christ—was located in front of the main altar. (Originally it was probably attached to a wooden screen in front of the altar. Since the recent restoration of the church, it has been hanging behind the main altar; see photo at the beginning of this article. This gilt crucifix dominated the view of any worshiper standing in the nave of the Church of San Francesco. This “true” cross was the culmination of Piero’s history.

036Piero della Francesca: The Legend of the True Cross in the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username