The Exodus and the Crossing of the Red Sea, According to Hans Goedicke

Leading scholar unveils new evidence and new conclusions; search goes on for archaeological support

042

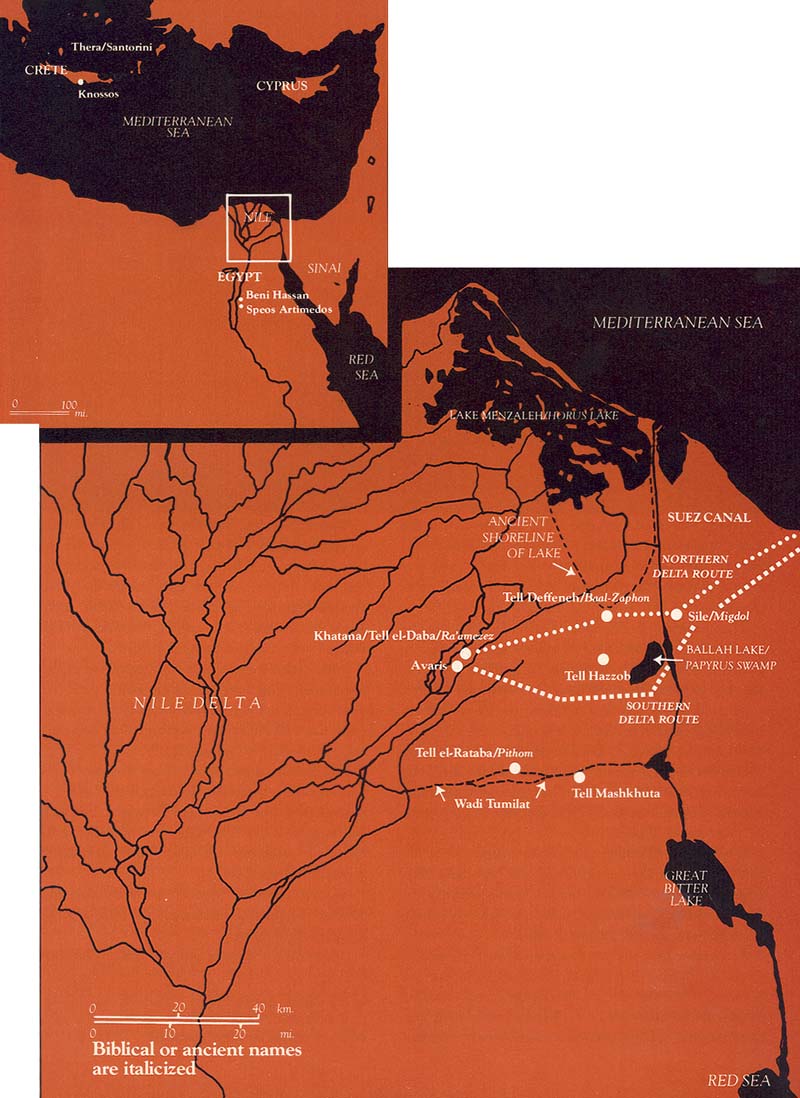

The crossing of the Red Sea in which the Egyptians drowned was an actual historical event that occurred in 1477 B.C. The miraculous episode took place in the coastal plain south of Lake Menzaleh, west of what is now the Suez Canal. The drowning of the Egyptians was caused by a giant tidal-like wave known as a tsunami which swept across the Nile delta, over Lake Menzaleh, inundating the plain south of the lake. The tidal-like wave was transmitted by a volcanic eruption in the Mediterranean Sea.

These are some of the major conclusions recently announced by Hans Goedicke, chairman of the department of Near Eastern Studies at Johns Hopkins University and a world-famous Egyptologist. Generally regarded as a careful and cautious scholar, “not given to wild speculation,” Professor Goedicke reached his new conclusions after a lifetime of study.

Professor Goedicke’s interpretations are causing tsunamis of their own in the scholarly world. Almost every aspect of his theories runs counter to a substantial body of prevailing scholarly thought. There is no question, however, that Professor Goedicke is also causing a lot of rethinking about some old cruxes.

In the past, some scholars have even questioned whether there was an Israelite Exodus from Egypt. Those who accept the Exodus as an historical event generally place it in the thirteenth century B.C., more than 200 years later than Professor Goedicke. Where the crossing of the Red Sea—or more accurately, the Reed Sea—took place is generally regarded as anybody’s guess among the many locations that have been suggested.

If Professor Goedicke’s dating of the Exodus is correct, the Pharaoh of the Exodus was a woman—Hatshepsut, who ruled Egypt from 1487 B.C. to 1468 B.C. Professor Goedicke has even identified a hieroglyphic inscription of Hatshepsut, which, he says, is an independent Egyptian account of the Exodus!

The announcement of Professor Goedicke’s conclusions created front-page headlines in The New York Times, and prominent articles in The Washington Post, Newsweek, and daily newspapers around the country. Public discussion ensued in letters to the editor.

Professor Goedicke plans to return to Egypt in September. Before he leaves, he says he will announce “another sensation.” In Egypt, he will continue his archaeological survey. He confidently expects to find additional archaeological evidence to sustain his conclusions. He even expects to be able to trace the flood waves. “The chances are 70–30 that I will find the point of crossing [of the Reed Sea] with archaeological evidence to support it,” Professor Goedicke told BAR.

What follows is a close paraphrase of Professor Goedicke’s analysis of the Exodus story in the Bible and the extra-Biblical evidence which led him to date the miraculous crossing of the Reed Sea to “the early morning hours of a spring day in 1477 B.C.”

Israelite Mercenaries Lose Freedom in Egypt

In the Bible, the story of Joseph explains how the Israelites came to Egypt. The nuclear group which emerged in Egypt came from southern Palestine, the area of Hebron and Mamre (Genesis 18:27), where its members had acquired land. They were not indigenous to the Hebron area, but had immigrated. The Exodus people in Egypt therefore came from a sedentary background. They were not, as is so commonly argued, a nomadic people who drifted into Egypt.

Moreover, the Israelites came to Egypt as a result of an official invitation. A detail like this is unlikely to be contrived, says Professor Goedicke, so it is very probably historically accurate. That the invitation to come to Egypt was extended through the mediation of one of the group’s members (Joseph) is so ingenious that this detail, too, must be factual.

Looking at the external evidence, we find that between 1770 B.C. and 1540 B.C. (Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period), Semites occupied high positions in Egypt. At 043least two Semites bore the designation “King.” The Hyksos invaders of Egypt were Semites and one of their kings (Apophis) who ruled Egypt had a “chancellor” named Yakob-el. Yakob is Hebrew for Jacob; el is a name for God often used in the Hebrew Bible.

According to the Bible, those who came down to Egypt settled in Goshen (Genesis 47:27). In this area, assigned to them by Pharaoh, the group settled for more than a generation, making its living through animal husbandry, as shepherds (Genesis 45:10). During this time, they enjoyed advantageous conditions.

Under a Pharaoh “who did not know [acknowledge] Joseph,” (Exodus 1:8) this situation changed abruptly. Somehow connected with the changed situation, these people were required to build the “store cities” of Pithom and Ra’amezez. Consequently, a leader of the group asked Pharaoh’s permission, on behalf of the group, to emigrate.

The group previously had the right to pursue its own support. It was apparently very successful at that. The requirement that the group build the store cities of Pithom and Ra’amezez somehow endangered or eliminated its freedom to pursue its own support.

It is sometimes suggested that the core group of Israelites were free nomads who must have considered construction work an insult and injury. This is a foolish suggestion. First, as already suggested, these people were not nomads. And, in any event, nomads, in general, are not so heroically proud that they would categorically reject the opportunity to enhance their meager livelihood by an occasional job, and building with unbaked bricks is neither a long, drawn-out, nor a particularly tedious task. A sizeable house can be built by three or four men within a few days.

Thus, it cannot have been the construction work itself, the duration of which would have been limited and anticipated, which instigated the group’s decision to emigrate. The decision to emigrate must have been motivated by the consequences of the completed project.

The Bible says nothing about the position of this group of people within Egyptian society, except that it was not an integral part of that society. The fact that the Palestinians had come to Egypt by the invitation of a Pharaoh shows that they stood in a direct relation to his authority. This did not change during their stay in Egypt; they had to ask the Pharaoh for permission to leave the country. Only after it was granted could they depart. This administrative process is understandable only if an employment bond existed between the group and the Pharaoh. Accordingly, we should view the Exodus group as being mercenaries who wanted to leave the service of the Pharaoh.

What these people considered unacceptable was that in contrast to the independence they previously enjoyed in their own support, they were now to be gathered together and provisioned as a group in the store cities they were required to build.a

According to the plan of the Pharaoh “who did not acknowledge Joseph,” the mercenaries, who had until then lived individually, were to be settled in the two garrison towns of Pithom and Ra’amezez.

Ra’amezez and Pithom Identified

An investigation of the geography of Goshen, as well as the location of Pithom and Ra’amezez, helps us to understand the need for mercenaries at this location.

Goshen lies in the western part of the Wadi Tumilat, between Tell el-Kebir and Tell el-Rataba. Within this area, the store cities of Pithom and Ra’amezez lie at Egypt’s eastern frontier, where the Nile Valley had to be protected against potential intruders, whether by invasions or infiltration. These sedentary herdsmen were thus originally employed by Pharaoh as mercenaries to guard the frontier.

The location of the two store cities mentioned in the Bible is important not only because it helps explain the need for mercenaries (commonly used by the Egyptians) at this location, but also because these cities provide an important key for the dating of the Exodus.

For a long time, Pithom was identified with Tell Mashkhuta. But very recent excavations of Tell Mashkhuta by John S. Holladay of the University of Toronto have demonstrated that there are no remains here earlier than the Persian Period (525 B.C.–332 B.C.).b It seems clear, Professor Goedicke says, that Pithom is not Tell Mashkhuta, but Tell el-Rataba, a name corresponding to ras el wadi, that is, at the “head of the wadi or valley.” At 044Tell el-Rataba, which Professor Goedicke is excavating, remains have been found which unquestionably reflect Syro-Palestinian culture and date to the Middle Bronze Age II (1700 B.C.–1500 B.C.). Some of the pottery may even have been imported from Palestine.

The store city of Ra’amezez is widely, but incorrectly, equated with Pi-Ramesses, the Residence of the Ramessides. The construction described in the Bible is generally associated, again incorrectly, with the building of the Residence, which occurred in the reign of Ramesses II who ruled from 1290 B.C. to 1224 B.C. The Residence of Ramessides was not a single building but was in fact a kind of megalopolis—a large, densely populated area.1

If Pi-Ramesses was built by the Exodus people, it is obvious that the Exodus must have occurred in the 13th century B.C.

But the fact is that the store city of Ra’amezez cannot be identified with Pi-Ramesses, the Residence of the Ramessides. This identification is impossible phonetically, as has been demonstrated conclusively more than 15 years ago.2 Moreover, the Residence of the Ramessides is never denoted in Egyptian sources by the use of the royal name Ramesses alone. When the Residence of the Ramessides is referred to, the royal name is always connected with the Egyptian word pr, meaning house or residence: The reference is always in the form “Per Ramesses.”

Accordingly, the Biblical designation of one of the store cities as Ra’amezez provides no basis for concluding that the Exodus occurred in the 13th century B.C.

There is another reason why the Exodus cannot have occurred in the 13th century B.C. The earliest reference to Israel outside the Bible is on the famous Merneptah Stele. Merneptah was the successor of Ramesses II. Merneptah’s famous stele records his military achievements to the fifth year of his reign (1219 B.C.). By that time, Israel had such significance as a people that it is listed among these achievements: “Israel’s seed is not,” Pharaoh Merneptah boasted, with obvious exaggeration. The people Israel was plainly a political problem for Merneptah. This could hardly have been the case if the people who became Israel had so recently become a “people” after the Exodus. Are we to believe that within 75 years at most, the Exodus group became a political and military power of the magnitude reflected in the Merneptah stele, especially after a 40-year desert sojourn? It is impossible to date the Exodus to the 13th century in light of the Merneptah stele.

Let us return, therefore, to the identification of the Biblical store city of Ra’amezez. The megalopolis area known as the Residence of the Ramessides has now been identified with certainty as the area of Qantir-Khatana, east of the Pelusian Branch of the Nile.3 Within this area, at least two cities existed long before the time when the area became known as Per Ramesses, the Residence of the Ramessides. One of these earlier cities was Avaris, the capital of the Hyksos kings (1650 B.C.–1542 B.C.) and the other was the border town at the beginning of the two delta roads leading to the so-called Philistine route to Palestine. This border town, written in hieroglyphic transliteration as R

The final element in demonstrating the validity of this identification of Tell el-Daba with Biblical Ra’amezez is that hieroglyphic R

Summarizing our story to this point, a group whose members had originally come to Egypt from Palestine on Pharaoh’s invitation, settled in Egypt’s eastern frontier region and practiced animal husbandry. The group’s role is to be understood within the framework of general frontier guarding and for this these people received the privilege of individual settling. After a considerable period of time, however, the privilege of free support was withdrawn and the people were instead gathered into garrisons, where they were provisioned by the Pharaoh. Because of this curtailment of their privileges, the group requested release from their employment; this release was granted after numerous delays, which found their poetical reflection in the Ten Plagues.

Fleeing Israelites Follow Southern Delta Route

Although the Bible does not tell us explicitly where they intended to go, it seems obvious that their destination was their ancestral home in southern Palestine. We can infer as much from the fact that they took Joseph’s bones with them (Exodus 13:19), doubtless for re-burial 046in the family tomb at Hebron (Genesis 50:13). We are also told that the shortest route to their destination was the Way of the Philistines (Exodus 13.17), another indication that their destination was southern Palestine. (The reference to the Philistines is an anachronism because this people did not walk through the pages of history until a later period, but this point is irrelevant for present purposes).

Two delta roads to the northern Sinai route to Palestine (the way of the Philistines) started at Biblical Ra’amezez (Khatana) or Tell el-Daba. One, the shorter northern road, was used in summer when there was no danger from the sea or the swelling Pelusian Branch of the Nile which this road followed just to the south of the river. The second more southern route located in the desert plateau was used in winter. Analysis of the Biblical text indicates that the Exodus group started out on the northern route (as would be expected in the spring after the winter rains had ended) but then switched to the more southern route. The critical verse is Exodus 14:2:

Yahweh said to Moses: Tell the Israelites to turn back (or turn around) and encamp before Pi-hahiroth, between Migdol and the Sea, before Baal-Zephon; you shall encamp facing it, by the sea.

Several aspects of this verse are to be noted. First, the location is indicated in detail and with great precision. Second, the “sea” is mentioned twice. Third, there is a change of route—the Israelites are to turn around or to turn back.

The instruction to turn around can only mean that the group was to abandon the northern summer road to Palestine across which, until then, it had been proceeding, and to take instead the more southerly route. Why?

The motive for this departure from the main northern road is suggested in Exodus 14:3: “For Pharaoh will say of the children of Israel: They are entangled in the land, the wilderness has shut them in.” In other words, the group wanted to avoid its pursuers. That they were militarily pursued, despite the permission to emigrate, is stated with all clarity in the Biblical text.

We should remember that these people were not without military experience. They had previously been employed as mercenaries to prevent border infiltrations. The decision “to turn around” reflects a decision to shake off their pursuers by a feigned maneuver—to take a different route than the one they started on. The pursuing troops must have been near. Otherwise, the pursued would not have known they were being chased. Because of its military experience, the Exodus group must also have prepared for the possibility that the feigned maneuver—a change of route—might not succeed. If they were found by their pursuers despite the change of route, the fleeing people had to be in a defensible position. In a mostly flat area, this meant that the threatened group would have naturally retreated to an elevated position.

Flash Flood Drowns Egyptians

Can this spot, this elevated position, be identified? Professor Goedicke believes it can. We are helped by the detailed description of the location where, in Exodus 14:2, the Israelites were told to encamp and where, we later learn, the miracle of the crossing of the sea occurred (Exodus 14:9). Pi-hahiroth cannot be securely identified, but the other locations can. Baal Zaphon is by general agreement identified with modern Tell Defenneh. Migdol is the Semitic word for fortress. It probably refers to an Egyptian frontier fortress. In Exodus 13:20, the first fixed point on the Exodus journey, presumably after a journey of several days, is given as “Etham at the edge of the desert.” Etham is a transcription of the Egyptian word htm. which, like migdol, means fortress and probably refers to the same frontier fortress as migdol. Etham has been identified as the ancient Egyptian fortress at Sile, and Migdol is no doubt to be identified with this same fortress.

Midgol (Sire) and Baal-Zaphon (Tell Defenneh) are on an approximately east-west line. A look at the map will help identify the references to “sea” in Exodus 14:2. To the north of the line lies Lake Menzaleh, which the ancient Egyptians called the “Horus Lake” and to the south lay Ballah Lake, which the ancient Egyptians referred to as “Papyrus Swamp.”

In this area, there is only one distinctive elevation to which the fleeing Israelites could repair if their change of direction did not successfully mislead the pursuing Egyptians and a direct military confrontation became inevitable. That elevation is Tell Hazzob.

Tell Hazzob, as can be seen from the map, is six miles south of Tell Defenneh (Baal-Zaphon) and 15 miles west-southwest of the ancient fortress at Sile (Migdol). Tell Hazzob is also six miles west of Ballah Lake (the Papyrus Swamp) and 6½ miles south-southeast of Lake Menzaleh (Horus Lake).

In short, for a hard-pressed group determined in the extreme, Tell Hazzob represented the only opportunity of a meaningful defense.c

Apparently, the feint did not work. Pharaoh’s men 047pursued the Israelites who retreated to Tell Hazzob to await the inevitable attack.

However, it did not come to the last battle. A miracle happened, which destroyed the pursuers and gave the hard-pressed Israelites the opportunity to leave unharmed. That experience at the edge of the desert transformed a more or less haphazard group into a unit; not only did a group consciousness evolve but also the conviction of a special divine protection developed. This “miracle of the Sea,” is not only the basis of Israel’s self-understanding, but also of its relationship to God as the “children of God,” since God’s might had manifested itself so obviously to its advantage.

The detailed description in Exodus 14:5–30 makes it possible to grasp the uniqueness of the physical event:

Pharaoh and his courtiers ask themselves, “Why have we released the Israelites from our service” (Exodus 14:5). Pharaoh decided to take 600 of his best chariots to pursue the Israelites (Exodus 14:6): “The Egyptians gave chase to them, and all the chariot horses of Pharaoh, his horsemen and his warriors overtook them encamped by the sea, near Pi-hahiroth, before Baal-Zaphon. As Pharaoh drew near, the Israelites caught sight of the Egyptians advancing upon them and were greatly frightened (Exodus 14:9–10).

The rest we know—how the Lord parted the sea while the Israelites passed through during an entire night. (Exodus 14:20–21). At the morning watch (Exodus 14:24), Yahweh looked down and saw the Egyptians in hot pursuit. At daybreak (Exodus 14:24) he brought the waters together and drowned the Egyptians … Thus Yahweh delivered Israel that day from the Egyptians … “And when Israel saw the wondrous power which Yahweh had wielded against the Egyptians, they feared Yahweh. They had faith in Yahweh” (Exodus 14:26–31).

Embedded in the poetical formulation of the Bible, the following facts can be discerned: During the night Moses led his group to the south away from the main road. The Pharaonic troops followed them during the same night, in order to be ready for battle in the morning. As dawn broke, the departing group of former mercenaries and the Pharaonic troops confronted each other, ready to fight. The Egyptian chariotry standing in the plain was wiped out, however, by a flash flood, while the defenders on the height of Tell Hazzob remained unharmed. By looking for the cause of the flash flood, we will find evidence for dating the Exodus.

At the outset, we should note that in Egypt proper there is no natural basis for an experience like the “miracle of the Sea.” The Nile flood arrives gradually and falls in the same fashion. The Mediterranean is not rough 048like the North Sea or the Atlantic Ocean. The “miracle of the Sea” must thus be seen as an exceptional phenomenon of nature, which in turn shows that its description can only stem from a real experience and not simply from literary imagination.

Hatshepsut Identified as Pharaoh of Exodus

In Exodus 13:21–22 and in Exodus 14:19 we learn that a “pillar of cloud” by day and a “pillar of fire” by night stood before the departing Israelites. These two signs are of a conspicuously volcanic nature. Moreover, these phenomena stood in front of the emigrants moving north. It is thus necessary to look for the source of the volcanic phenomena somewhere to the north of Egypt, that is, in the Mediterranean Basin.

The most important volcano in the Mediterranean region is located on the island of Thera/Santorini, 30 miles north of Crete. Seismologists have there established, on the basis of the tephra-structure, three major ancient eruptions, one about 1600 B.C., another about 1475 B.C. and a third in the twelfth century B.C. Since the first and third cannot be connected with the Exodus, it must be the second which is relevant for our purposes. The volcanic eruption of Thera/Santorini about 1475 B.C. was important not only for the Exodus. On the basis of Egyptian sources, it has been established that the high Minoan civilization of Knossos on the island of Crete was destroyed about 1475 B.C., and archaeology has linked this destruction beyond doubt with an outbreak of the Thera volcano.

Such an eruption must have triggered a tsunami, a huge tidal-like wave, which simply drowned Knossos. This tsunami would have reached the Nile Delta and flooded it within three hours as it rolled through the southeastern Mediterranean. Then it passed through the shallow Lake Menzaleh and filled the plain south of the Pelusian branch of the Nile to the edge of the elevated desert plateau—drowning the Egyptians waiting to confront the Israelites on Tell Hazzob.

The reigning monarch in Egypt at this time was Queen Hatshepsut. Surprisingly enough, two bits of evidence provide some corroboration for the conclusion that the Exodus event occurred during Hatshepsut’s reign (1487 B.C.–1468 B.C.).

The first is some unquestionably Semitic inscriptions which were found in the Sinai at Serabit el-Khadem. These inscriptions can be dated with certainty to the reign of Hatshepsut. There are no other traces of possible participants in the Biblical Exodus which have been found in the Sinai.

Although these inscriptions have not yet been fully deciphered—they are written in an extremely archaic alphabet known as proto-Sinaitic script—it is clear that the word Ba-alat (the female of ba-al) appears repeatedly. Ba’alat means mistress and it is often taken to refer to an Egyptian goddess such as Hathor. But it can also have a political referent. Did the ancient Israelites of the Exodus carve these inscriptions at Serabit el-Khadem? And were they referring to their former mistress Hatshepsut when they used the term Ba’alat?

Incidentally, the Biblical text makes it clear that after the “miracle of the Sea” the Exodus group was no longer threatened, but it nevertheless abandoned its original route to Palestine. Perhaps the main road became impossible or, more likely, the flash flood was seen as a sign from God not to move in the intended direction. Subsequently, the group moved, under extreme difficulties, to the Sinai. What remained of the group of emigrants was reconstituted there by Moses. The proto-Sinaitic inscriptions at Serabit el-Khadem are congruent with the picture painted in the Biblical text.

049

The second bit of evidence connecting Hatshepsut to the Exodus event is startling. It is an inscription carved in the entrance to a sanctuary at the edge of the desert.d The text of the inscription is a royal announcement by Hatshepsut. It is addressed to the entire population of Egypt, so similar copies were probably placed all over the country, although only this one, in a remote desert sanctuary, survived. The text is couched in the specific idiosyncracies of ancient Egyptian expression, which sounds stilted to modern ears, but it is not difficult to transpose it into modern parlance.

It tells of a people called “Amu” who had enjoyed special privileges. “Amu” is the Egyptian term for Semitic-speaking people from Palestine. They had settled in the region of Avaris in the northeastern Delta where, as we have seen, recent excavations have demonstrated the existence of a large community of Palestinians of Middle Bronze II date. Among these people, one group is singled out in the inscription as the object of Hatshepsut’s wrath. The group is referred to as shemau, that is, pasturalizing livestock-breeders. As we have seen, according to the Biblical text, that is how the ancient Israelites made their living when they came to Egypt.

In the Egyptian text, Hatshepsut’s ire is triggered by 050this group’s refusal to perform its assigned obligations. The overall subject of the inscription is Hatshepsut’s great building activity, which was accomplished by abolishing privileges. In the context of building activities, the abolished privileges clearly refer to the abolition of an exemption from the corvée, the impressment of labor for public projects. It can easily be inferred that these shemau from Palestine opposed the abolition of their exemption from the corvée.

The inscription explains that the shemau had not thought Hatshepsut would be successful in attaining ruling power. Apparently the shemau’s opposition had already begun in the years when Hatshepsut was still regent for her underage stepson Thutmosis III, whom she later pushed aside in the third year of his reign in order to have herself made king.e

After her takeover, her anger is directed against her opponents. Unfortunately, we are not told precisely what she did. However, the struggle apparently lasted over an extended period of time. The struggle did not end, as might have been expected, with the suppression or annihilation of her opponents: Instead, they are given permission to depart.

From her point of view, Hatshepsut handled her opposition brilliantly. Her decision was not simply accepted by the gods—the gods of Egypt went even further. Hatshepsut had refrained from destroying those who opposed her; the gods, however, in confirmation of her efforts, utterly annihilated them. The people who opposed Hatshepsut are called “the abomination of the gods.” “The earth,” we are told, “swallowed up their footsteps.”

We are not told directly how they were destroyed, but it is not difficult to figure out. Their destruction is attributed to the primeval father, literally, the “father of fathers.” This term is rooted in Egyptian mythology in which Nun, the primeval water, stands at the beginning of creation. Nun is also the principle of wateriness, and manifests itself in every form of water, whether river or sea. The destruction of Hatshepsut’s opponents then occurred when Nun, that is, “water,” came unexpectedly or “not at its season.” It “swallowed up” her opponents’ “footsteps.”

In the Egyptian version of the tale, not surprisingly, Hatshepsut’s opponents, rather than her own soldiers, are drowned.

In short, the Egyptian inscription describes how a group of Semites, who pursued pasturalism for a livelihood, opposed Hatshepsut when she cancelled existing privileges and drafted the people in a corvée to support her building activities. This happened at the beginning of her reign when she was still regent and not yet king, that is, between 1490 and 1487 B.C. After her takeover as king, she persecuted those who had put up resistance to her. Finally, she let them leave, dismissed them from her service. During their sojourn, the group is destroyed by an unexpected coming of the water, that is, “the Sea,” so that “the earth swallowed up their footsteps.”

“The similarities of this report with the Exodus-narrative,” states Professor Goedicke, “are so great that in my opinion there can be no doubt that we have here two accounts of the very same event!”

Of course, the different point of view of the narrator in the Egyptian inscription leads to diverging interpretations of the miracle of the sea, but the basic story is the same.

Although Hatshepsut’s inscription is not dated, circumstantial evidence suggests that the events described occurred in her 13th regnal year, which would place them in the year 1477 B.C.

Then it was that a group of Semites left Egypt to return to their ancestral home in Palestine. Since it was spring, they followed the northern, shorter route until they realized that they were being pursued. To escape their pursuers and to be in a position to defend themselves if they could not avoid their pursuers, they turned south to an elevation at the desert edge, ready to take a stand against the pursuing troops of Pharaoh, who were positioned in the plain below them. At this tense moment, when destruction seemed imminent, a miracle happened. Caused by an outbreak of the volcano of Thera, a tidal-like wave rolled through the southeastern Mediterranean, passing through Lake Menzaleh and filling the plain where the Egyptians were encamped. In the early morning hours of a spring day in 1477 B.C., Professor Goedicke concludes, the earth did not “swallow up the footprints” of those who had opposed Hatshepsut, as she claimed, but instead the pharaoh’s troops were drowned. “And Israel was born in the ‘miracle of the Sea,’ the theophany of its God.”

(BAR wishes to thank Professor Goedicke for his assistance in the preparation of this article.)

The crossing of the Red Sea in which the Egyptians drowned was an actual historical event that occurred in 1477 B.C. The miraculous episode took place in the coastal plain south of Lake Menzaleh, west of what is now the Suez Canal. The drowning of the Egyptians was caused by a giant tidal-like wave known as a tsunami which swept across the Nile delta, over Lake Menzaleh, inundating the plain south of the lake. The tidal-like wave was transmitted by a volcanic eruption in the Mediterranean Sea. These are some of the major conclusions recently announced by Hans Goedicke, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

There is a parallel to this event from the time of Ramesses III (1183–1152 B.C.): After a mutiny Ramesses III quartered the mercenaries who, until then, had lived as “military settlers” in garrisons where their provisioning was arranged.

Although Mashkhuta excavators have not found occupation levels earlier than the Persian dating period, they have found Hyksos or pre-Hyksos burials dating to the Middle Bronze Age II A. These burials, say the excavators, “give evidence for some yet undefined earlier use of the site.” See Burton MacDonald, “Excavations at Tell el-Mashkhuta,” Biblical Archeologist Vol. 43, No. 1, p. 49 (1980). Some of the burial practices were similar to the burial practices found among Asiatics buried at Tell Daba which Professor Goedicke believes to be Ra’amezez.

Tell Hazzob is unexcavated. Clearly it should yield to the excavator’s spade. The Arab name for the site is Umm-Garf which means the mother of potsherds.

This inscription has long been known and was first published in 1880. It is famous because of its reference to Asiatics or the Hyksos invaders of Egypt. No one previous to Professor Goedicke however, has related the inscription to the Exodus.

The inscription was translated by Sir Alan H. Gardiner, the dean of hieroglyphic translators, in an article published in 1946 (“Davies’ copy of the Great Speos Artemidos Inscription,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Vol. 32, p. 43.). Gardiner referred to the inscription as a “difficult text” and concluded his translation with these words: “I cannot refrain from once more stressing the highly speculative nature of my results.”

The inscription is located high up on the facade of a rock temple built by Hatshepsut and dedicated to the local lioness goddess Pakhet. The temple is located at Speos Artemidos (known locally as Istabl Antar), just south of Beni Hassan in Middle Egypt.—Ed.

Professor Goedicke deliberately refers to Hatshepsut as a king despite the fact that she was a woman. She was pictured with an artificial beard such as male rulers wore and with a deliberately flattened chest. Literary references to her include all the usual male epithets applied to a king except the epithet “strong bull.”