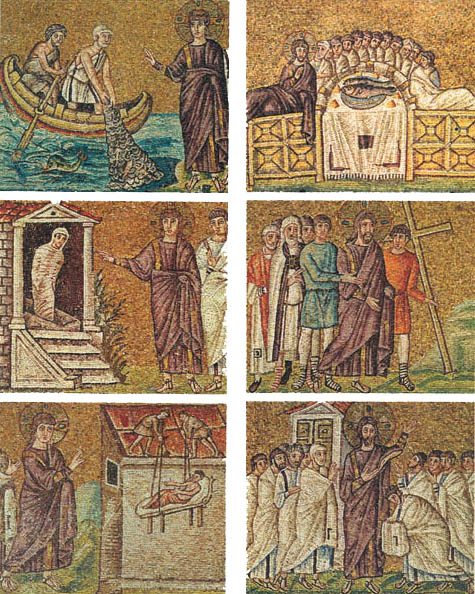

In the upper reaches of the Church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, just below the painted wood ceiling, appears a striking series of 26 mosaics portraying the life and passion of Jesus. Dating to the early sixth century, they constitute one of the oldest—perhaps the oldest—extant monumental series of images depicting Jesus’ life (see photos of mosaic panels from Ravenna below).

The small mosaic panels are divided thematically: Those on the left (northern) wall of the church are devoted to Jesus’ ministry. They show Jesus teaching (addressing the Samaritan woman at the well, for instance, and making an example of the widow who donated her last mite to the Temple), healing (curing the paralytic, the hemorrhaging woman and the man born blind) and working wonders (producing wine at Cana and multiplying the loaves and fishes). Those on the right (southern) wall depict Jesus’ last days: They begin near the apse with the Last Supper and end with Jesus’ post-Resurrection appearances to the apostles. In the final panel, next to the door, Jesus displays his wounds to the doubting Thomas.

But the mosaics are not divided merely in terms of what they depict. They are also divided in the way they depict Jesus. As many art historians have noted, in the scenes on the left Jesus has light hair, a fair complexion and no facial hair. In the passion scenes on the right wall, Jesus has a darker complexion and a beard.

Something similar appears more than a century earlier in Rome, in the Mausoleum of Santa Costanza, named for the emperor Constantine’s daughter and probably intended as her tomb. Here, mosaic artists decorated two adjacent apses in the perimeter wall of the circular building: In one apse we see a youthful, unbearded Jesus dressed in white and standing as he gives the scroll of the Law to Paul (photo, above); in the other, an older, darker, bearded Jesus, dressed in purple and enthroned on the orb of the world, passes the keys of the church to Peter (photo, below).

Based on the style and technique in the Santa Costanza mosaics, we must assume that they were made at the same time by the same group of artisans (although some details of the second apse may have been the work of a later restorer). The same is true of the mosaics of Jesus in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo: The whole cycle was produced by the same workshop. Thus, in each case we can be sure the variations in Jesus’ portrait were intentional.

Furthermore, most early Christian images of Jesus—whether painted on the walls of catacombs, carved in relief on sarcophagi or set in mosaic tiles—can be divided into these two general types of portraits: the beautiful, youthful, long-haired Jesus and the older, bearded Jesus.

The first portrait type appears on the many early Christian sarcophagi in the Vatican Museum, for example, and in wall paintings from the Roman catacombs, including the catacombs of Callixtus, Sebastian, and Peter and Marcellinus. Here Jesus has a youthful appearance, beardless face, long curly hair and a graceful (if not sinuous) body and posture—just as in the mosaics on the left wall at Sant’Apollinare Nuovo. In these images, he wears a tunic and pallium (cloak or mantle), often of white cloth, and sandals on his feet. Most of the scenes in which he appears this way are narrative images of him healing, wonder-working or raising the dead. He also appears like this when he is entering Jerusalem. When he is working wonders or raising the dead, he typically carries a wand.

The second portrait type—in which the older Jesus has a beard and often wears purple robes—is seen in one or two early images of Jesus’ giving of the Law (including a late-fourth-century sarcophagus relief in the Musée Réattu, in Arles). The bearded Jesus also appears in a rare depiction of him with a bare chest and with his disciples at his feet, making him look like a philosopher with his pupils, on a late-third-century relief now in Rome’s National Museum (see photo of Roman sarcophagus relief),1 as well as in later images of Jesus ascended, such as the early-sixth-century apse mosaic from Saints Cosma and Damiano in Rome (see first photo of apse mosaic above), and of Jesus enthroned, including the late-fourth- or early-fifth-century apse mosaic of Rome’s Santa Pudenziana (or the second apse mosaic from the mausoleum of Santa Costanza above). What may be the earliest bust portrait of Jesus, a late-fourth-century ceiling fresco in the Catacomb of Comodilla, also shows him with a beard. And when crucifixion images begin to appear with some regularity in the sixth century, they, too, generally depict Jesus as bearded.

Both types—youthful and bearded—are borrowed from pagan art. Early Christian artists regularly adapted pagan imagery for their own purposes. In Christian catacomb paintings and sarcophagi reliefs, Job is depicted as a philosopher; Jonah, sleeping under the gourd tree, appears in the posture of Endymion (the moon goddess’s lover, who slept eternally); the ubiquitous image of the Good Shepherd is borrowed from pagan iconography of Hermes Criophorus (Sheep-bearer); and bucolic images of Jesus surrounded by wild animals are based on scenes of Orpheus playing his lyre or pipes. It is thus not surprising that Jesus’ face would be borrowed from pagan imagery. But, as we shall see, when Christian artists appropriated pagan figure types, they transformed their meaning.

In his beardless portraits, Jesus bears a striking physical resemblance to certain junior or transitional pagan gods—including Apollo, Dionysus, Hercules, the sons of Jupiter and other semidivine heroes—who are associated with working wonders, shepherding souls through the underworld, bringing light from the darkness, being born through miraculous or divine conception, or dying and then rising again. The resemblance is so strong that art historians have at times been unsure whether an image depicts Jesus or a pagan deity. In a mausoleum beneath the Vatican, a partially preserved vault mosaic (see photo of mausoleum mosaic) depicts a haloed sun-god carrying an orb and driving a quadriga (chariot drawn by four horses). But although the late-third- or early-fourth-century image might appear to represent Apollo or Sol, other images from the mausoleum (of a fisherman, Jonah and the Good Shepherd) indicate that this was a Christian tomb and that the god depicted is actually Jesus in the guise of a solar deity.

Christian writers, beginning with Justin Martyr in the second century, have long cited the parallels between the Jesus story and the myths of these gods, and have mentioned the possibility of conflation or confusion. Wrote Justin Martyr:

And when we say that the Word, who is the first born of God, was produced without sexual union, and that he, Jesus Christ, our teacher, was crucified and died, and rose again, and ascended into heaven, we propound nothing different from what you [polytheists] believe regarding those whom you esteem sons of Jupiter.2

The second portrait type most closely parallels images of the senior, enthroned father gods—Jupiter, Neptune and Serapis. In the earliest Christian images, it is most often found in scenes of Jesus ascended and enthroned, as in the apse mosaic at Santa Pudenziana or Santa Costanza.

Many historians have tried to interpret these contrasting portraits of Jesus in terms of early church theology. In the fourth and fifth centuries, the so-called Arian or Trinitarian Controversy focused on the relationship between God and the Word (Logos). Was the Word coeternal and of the same nature as God the Father (as the orthodox church would maintain) or was the Word in some way inferior to (that is, subordinate to and created by) God the Father, as the Arians believed? In the fifth century, the central controversy was the so-called Nestorian or Christological controversy, which revolved around the dual natures of the Incarnate Word, Jesus Christ, and asked how Jesus could be both human and divine. The Nestorians and others asserted the strict distinction of two unmixed natures (human and divine) in Christ. Most historians view the Arians and Nestorians as the “losers” of the debates, although their positions were incorporated in subtle ways even in the statements of the church councils, and their viewpoints continued to affect Christian piety and even visual presentations of Christ.

We do have early Christian art produced by Arians. Indeed, the mosaics of Jesus in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo were commissioned by the powerful Arian leader Theodoric, an Ostrogoth who conquered Italy in 493 and made Ravenna his capital. He built Sant’Apollinare Nuovo (which he called Christ the Savior) as his palace chapel and covered its interior with brilliant mosaics.3 Many of the mosaics from Sant’Apollinare Nuovo were effaced when the Byzantine general Belisarius recaptured Italy in 540 and the emperor Justinian made Ravenna his own capital. Justinian restored Theodoric’s church to the Orthodox Church, renaming it for St. Martin, persecutor of the Arians. (The church obtained its present name only in the ninth or tenth century.) Theodoric’s mosaics of Jesus’ life were among the few to survive Justinian’s extensive “renovations” to the interior.

Those scholars who seek Arian interpretations of Theodoric’s mosaics tend to conflate Arianism with Nestorianism and interpret the youthful Jesus on the northern wall as representing Jesus’ divine nature and the bearded Jesus as representing his human nature.4 Why these “Arian” mosaics from Sant’Apollinare Nuovo survived Justinian’s purge when other mosaics were removed from the church is puzzling. Was it simply that the mosaics of Jesus in the highest register of the walls were so difficult to see from the ground that they were deemed unthreatening? It seems more likely that they survived because they were both beautiful and useful didactically and because their message was not seen as especially heretical. The mosaics that were effaced included images of Theodoric’s court: Their removal was clearly intended to serve as a kind of damnatio memoriae and cannot be attributed to any objectionable theology. The mosaics of Jesus may have survived because the iconography could be interpreted to suit either an Orthodox or a non-Orthodox, Arian Christology.5 If so, we cannot define the two portrait styles in terms of Arian theology.

So why was Jesus portrayed two different ways? A closer reading of early Christian writings offers another possible explanation.

Our earliest written source, the New Testament, tells us nothing about Jesus’ appearance: It never mentions the color of Jesus’ eyes, the length of his hair or his beard, his height, his weight or any other physical attribute. So some early Christians turned to the Old Testament to find clues to how the messiah should look. The contrasting descriptions they found might be the source for the belief that Jesus should be depicted two distinct ways. The second-century church fathers Justin Martyr and Origen point to Isaiah 53 as evidence that Jesus was unattractive: “He [the messiah] has no form nor glory, nor beauty when we beheld him, but his appearance was without honor and inferior to that of the sons of men.”6 At the same time, Origen and others cite the portrayal of God in Psalm 45 as testimony that Jesus was the “most handsome of men” (Psalm 45:2).7

So, in image and text we find two contrasting images of Jesus: youthful/mature and handsome/ugly. But what do they mean?

One possibility, as art historian Thomas Mathews of New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, puts it, is that the two images show Jesus as winner in a clash between the pagan and Christian gods. By subsuming the attributes of the young and old pagan gods, Jesus triumphs over both.8 He is everything they are, but more—and all rolled into one divine being. Therefore, the art presents Jesus as both Jupiter and Apollo, both Serapis and Dionysus—and greater than them all.

Augustine suggested a second possibility—that everyone has a different image of Jesus. He wrote:

The physical face of the Lord is pictured with infinite variety by countless imaginations, though whatever it was like he certainly had only one. Nor as regards the faith we have in the Lord Jesus Christ is it in the least relevant to salvation what our imaginations picture him like…What does matter is that we think of him as a man.9

The fourth-century bishop Cyril of Jerusalem added:

The Savior comes in various forms to each person according to need. To those who lack joy, he becomes a vine, to those who wish to enter in, he is a door; for those who must offer prayers, he is a mediating high priest. To those in sin, he becomes a sheep, to be sacrificed on their behalf. He becomes “all things to all people” remaining in his own nature what he is. For so remaining, and possessing the true and unchanging dignity of Sonship, as the best of physicians and caring teachers, he adapts himself to our infirmities.10

A final possibility—one that strikes me as being most closely allied to fourth- and fifth-century questions about Jesus’ divine and human natures—is that these two distinct faces of Jesus (especially as depicted in the Sant’Apollinare Nuovo mosaics) do illustrate the distinct natures in Christ—but not in the way the strict dualists or Nestorians would want it. Rather than two unmixed natures, one human and one divine, we have instead a kind of progressive glorification of the Son—or, more subtly, we have a progressive manifestation of his glory to human view.

I agree with Thomas Mathews that earlier fourth-century Jesus portraits borrow from two types of pagan deity portraits—those of the youthful, semidivine miracle workers and those of the supreme, father gods. I would argue, however, that in the later iconography, as at Ravenna, the two portrait types express Jesus’ transformation from teacher and miracle worker (in his earthly ministry) to a glorified Son of God (in his passion).11

If we look at the Sant’Apollinare Nuovo mosaics sequentially, we find that this change in Jesus’ appearance is first visible in the Last Supper mosaic. Something happens at that meal to change the divine healer into the Supreme Lord and Savior. But what?

The account of Jesus’ last meal with his disciples in the Gospel of John may well be the source for this shift in imagery. John’s passion narrative begins with this meal, during which Jesus washes his disciples’ feet (John 13). This is the point where the Gospel of John shifts from a Book of Signs (an account of Jesus’ miracles as revealing his true nature) to a Book of Glory (an account of his growing power and authority stemming from his passion). The gospel reads: “And during supper, Jesus, knowing that the Father had given all things into his hands and that he had come from God and was going to God, got up from the table” (John 13:2–4). After washing the disciples’ feet, Jesus states: “You call me Teacher and Lord—and you are right for that is what I am” (John 13:13). Earlier, in John 7:39, we read that Jesus “was not yet glorified.” Several times we are told Jesus will be glorified (John 11:4, 12:16 and 12:23). Now, in John 13:31, Jesus tells his disciples: “Now the Son of Man has been glorified, and God has been glorified in him…Little children, I am with you only a little longer. You will look for me; and as I said to the Jews so now I say to you, ‘Where I am going, you cannot come’” (John 13:31–33). For John, the manifestation of Christ’s full glory is not the working of wonders and miracles, but the undertaking of a journey to a place where the disciples cannot follow him until later—a place of glory.

The two faces of Jesus in art reflect the gradual transformation in Jesus’ manifestation, first as miracle worker then as Lord and Savior. They distinguish between his earthly ministry and his heavenly mission of divine self-sacrifice and cosmic redemption.12

MLA Citation

Endnotes

Paul Zanker, The Mask of Socrates, trans. Alan Shapiro (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1995), pp. 289–292.

Theodoric also built a baptistery some distance from Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, with a mosaic program modeled on the earlier “Orthodox” baptistery (the Neonian Baptistery). All that is left of the decoration of the “Arian” baptistery, however, is a medallion showing the baptism of Jesus and the ring of processing apostles just below. The Jesus image here is significantly different in appearance from the Jesus in the Orthodox baptistery. As in the miracle mosaics from Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, the Jesus of the Arian baptistery has no beard, while the earlier Jesus of the Orthodox baptistery (presuming the restorers kept the original facial type) was a bearded, older-looking figure. See Robin M. Jensen, “What Are Pagan River Gods Doing in Scenes of Jesus’ Baptism?” BR 09:01.

See Neil MacGregor with Erika Langmuir, Seeing Salvation: Images of Christ in Art (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), pp. 80–81, esp. 81: “The miracles and teaching [scenes in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo] reveal his divine nature, but it is as a man that Christ is betrayed, judged and led to his death.”

In truth, historians can say very little about the nature of Arian Gothic Christology or elaborate its differences from that of the Orthodox “conquerors” of Ravenna. We have no reason to think that the Arian Goths were also prone to Nestorianism, for instance.

Thomas F. Mathews, The Clash of Gods: A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1993).

Augustine, On the Trinity 8.7 (E. Hill, trans., The Trinity, in The Works of St. Augustine, part 1, vol. 5 [Brooklyn, NY: New City Press, 1991], pp. 246–247.)

Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures 10.5 (Andrew A. Stephenson, trans., The Works of Saint Cyril of Jerusalem, vol. 1 [Washington, DC: Catholic Univ. of America Press, 1969], p. 198). See also (for comparison), Origen, Against Celsus 2.64 or the Acts of John 87–89 for other examples of Jesus’ variant and changing appearance.

Certain younger pagan gods like Hercules and Dionysus were also depicted as both youthful and mature, bearded and unbearded, perhaps to suggest their own adaptability and multivalence, or even their ambiguous sexuality. Thus we may have here another kind of parallel between Christian iconography and that of the Greco-Roman religions.

Such an explanation might also account for the differences seen in the presentation of Jesus at his baptism in the Orthodox and Arian baptisteries. The designers of the Arian mosaics may deliberately have changed Jesus from an older figure to a younger (unbearded) one since he had not at that point “entered into his glory.”