The Wall That Nehemiah Built

024

Even before Nehemiah came from Babylonia to Jerusalem in the middle of the fifth century B.C.E., he knew that he wanted to rebuild the broken-down walls of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 1:3). When he arrived, he promptly made his famous night journey around the city, surveying the dilapidated city wall (Nehemiah 2:11–15). On the eastern slope, the wall of stones was so badly collapsed that his donkey could not navigate the path (Nehemiah 2:14).

Quite amazingly, especially considering its condition, the wall was rebuilt in a mere 52 days (Nehemiah 6:15). Nehemiah was able to accomplish this feat by assigning different sections of the wall’s rebuilding to various groups such as families, people from specific settlements, craftsmen’s guilds and so on (Nehemiah 3:1–32). Each section was denoted by 026specific public landmarks such as existing gates and other known structures. The landmarks in the eastern wall were private homes, probably because here the wall was built higher up on the slope than the old wall, at the top of the crest rather than nearer the floor of the valley, where it had been before the Babylonian destruction. True, the city became smaller this way (some of the old residential areas were now outside the city wall), but there were also fewer people living in the city, so there was no need for a big city.

In our recent excavations in the northern part of the City of David (the 12-acre ridge south of the Old City of Jerusalem), we have found a section of Nehemiah’s wall near the crest of the eastern slope—along with some extraordinary seal impressions featuring intriguing scenes and names. Some of them are people actually mentioned in the Bible.

It is most appropriate for me to publish this in BAR because an earlier BAR article resulted in our excavation. More than a decade ago, I wrote an article titled “Excavate King David’s Palace!” in which I identified the precise spot in the City of the David where I believed the palace was likely to be found.a New Yorkers Roger and Susan Hertog learned of my idea and decided to support an excavation to see if I was correct. The excavation began in 2005, supported by the Shalem Center Jerusalem and the Ir David (City of David) Foundation, under the academic auspices of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University Jerusalem. It was not long after we began to dig that a large building emerged—indeed, more massive than I had ever dared to imagine when I wrote my BAR article. I believe it is King David’s palace. That is the most likely identification.b Surely no one has come up with a better suggestion.

The walls of the building, which we call the Large Stone Structure, are between 7 and 11 feet thick. It sits on the highest point of the City of David, right on the eastern fortification line.

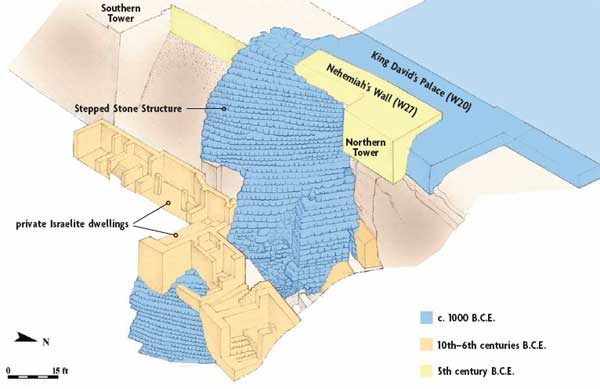

Just below the Large Stone Structure on the eastern slope is what is known as the Stepped Stone Structure. The Stepped Stone Structure is the largest Iron Age structure in all of Israel, rising to the height of a 12-story building. Even before our excavation, it was generally accepted that the Stepped Stone Structure was built to support a large building on top of the ridge. We have now excavated that building: the Large Stone Structure. The Stepped Stone Structure was originally built as a support for King David’s palace.

As we have exposed more and more of this building, the connection of the two structures becomes clearer. Wall 20 (W20) of the Large Stone Structure actually joins the Stepped Stone Structure.

027

As Wall 20 proceeds south, it comes to the remains of an ancient tower, which will now bring us to Nehemiah’s wall.

The remains of two ancient towers sit on the eastern fortification line of the City of David east of the Large Stone Structure. The Northern Tower, only a few feet away from the northeast corner of the Large Stone Structure, is the smaller of the two. Today it rises to a height of nearly 9 feet, but in antiquity it was, of course, much higher. It extends for almost 17 feet along the fortification line and is more than 9 feet wide before it leans against the city wall (Wall 27), whose remains were preserved for a few yards both north and south of the tower. About 65 feet south of the Northern Tower is the more massive and imposing Southern Tower, which, however, will play only a walk-on part in this drama. The city wall that extends on both sides of the Northern Tower also extends for a few yards north of the Southern Tower. Although a segment of the wall between the two towers is missing, it seems clear that the segments attached to the two towers are part of the same city wall.

The area adjacent to the Northern Tower had been excavated between 1923 and 1925 by R.A.S. Macalister and J.G. Duncan. As a result of these excavations, the Northern Tower was severely weakened, as we observed when we began excavating just west of the tower. In time, the cracks between the stones of the tower increased, and one crack in particular threatened to displace the whole southeast corner. We advised the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) of the unstable condition, and the IAA quickly initiated an excavation and restoration plan for the Northern Tower.

Whenever a stone was removed from the tower, it was numbered so it could eventually be returned to its original place at the end of the conservation process. When most of the tower had been dismantled, it became clear that the area under the tower should be excavated and restoration work should be postponed. This enabled us to accurately date the Northern Tower and the wall against which it leans on the west (Wall 27).

After the Northern Tower was dismantled, we could see that Wall 27 was built directly on top of Wall 20 of David’s palace. We could also see that Wall 20 and the Stepped Stone Structure were actually one structure. At that point, the Stepped Stone Structure is no longer rounded but becomes straight where it connects with Wall 20.

We have now excavated enough of the palace to know that Wall 20 forms its external wall. Wall 27 was later built on top of it as a continuation of a later city wall. The Northern Tower and Wall 27 are built in the same construction style, and both appear to belong to the fortification line along the eastern edge of the top of the hill.

With part of the Northern Tower dismantled, we 028excavated a small square beneath it, approximately 7 by 9 feet (2.2 x 2.8 m). An excavation is never without its surprises, and at this point there came a completely unexpected one: two dog burials. Unfortunately, no grave goods were buried with them—just two dogs. Our zooarchaeologist, Noa Raban-Gerstel of Haifa University, who studied the bones, tells us that the dogs died of old age. No signs of violence, sickness or malnutrition.

Before you conclude that these dog burials are irrelevant to our problem, consider the fact that dog burials in Israel are characteristic of the Persian period—when the Persian monarch Cyrus the Great permitted the Jews to return from the Babylonian Exile. The largest dog cemetery, with hundreds of burials, was discovered at Ashkelon on the southern coast of Israel. Excavator Lawrence Stager dates these burials to the first half of the fifth century B.C.E.,c the early part of the Persian period.

When we dug under the dog burials, we hit a stratum of brown earth nearly 5 feet thick filled with potsherds. We can date this stratum by the pottery, including the krater rims with wedge-shaped decoration that are typical of the period from the late sixth century to the early fifth century B.C.E. What is missing from this pottery-filled stratum is equally important. There was not a single “Yehud” impression on a jar handle in this stratum. Yehud is the name by which Judea was known in 030the Persian period. Yehud impressions date from the second half of the fifth century B.C.E. In Yigal Shiloh’s City of David excavations in the 1970s, he found large numbers of Yehud stamps. Our stratum with the dog burials, therefore, must be from the early part of the Persian period, the first half of the fifth century B.C.E. The Northern Tower and Wall 27 must have been built later. More precisely, we can say that the tower and its city wall were not built before the mid-fifth century B.C.E. (the terminus post quem). If they had been built many years after the time we suggest, this would have been indicated by different pottery and other finds that would have infiltrated into the stratum. But that is not the case. In short, the tower and wall were built at just the time when the Bible tells us that Nehemiah rebuilt the city walls of Jerusalem—around 445 B.C.E.

We can identify this tower and the walls that extend from it both north and south as part of Nehemiah’s rebuilding of ancient Jerusalem’s city wall. The section of the wall north of the Southern Tower would also have been part of this project.1 Wall 20 of David’s palace (by then destroyed) was simply combined with Wall 27 and used as a city wall. This composite wall is more than 16 feet thick. We found that the lower courses of the Northern Tower and the upper strata excavated underneath it abutted Wall 20. The wall is located at the crest of the eastern slope that Nehemiah chose to renovate in the shortest time under the most difficult conditions.

The Bible makes it clear why Nehemiah rushed to complete his rebuilding of the city wall (and its fortifications)—a feat accomplished, as I said, in 52 days: Judea’s neighbors opposed the project and ridiculed the Jews for their efforts (Nehemiah 4:1–2). The Bible tells us that “[their] foes were saying: ‘Before they know it or see it, we shall be among them and kill them, and put a stop to the work’ ” (Nehemiah 4:5 [verse 11 in English]). No wonder Nehemiah was in such a hurry to finish the job. He must have had exceptional organizational skills that enabled him to combine reconstruction with military defense. As he explains, “Half my men did work, and half held lances and shields, bows and armor” (Nehemiah 4:11 [verse 10 in English]).

But there was a price to be paid for the speed of the work. It was shabby workmanship. This is amply reflected in the poor quality of the Northern Tower and Wall 27. Macalister and Duncan, the tower’s first excavators, aptly described it: “The interstices [between the stones of the tower] are very roughly filled up with chips and with large quantities of mortar. The stones have no smooth finished face, and the filling of interstices is so carelessly done that the wall face presents a series of openings and cracks …”2

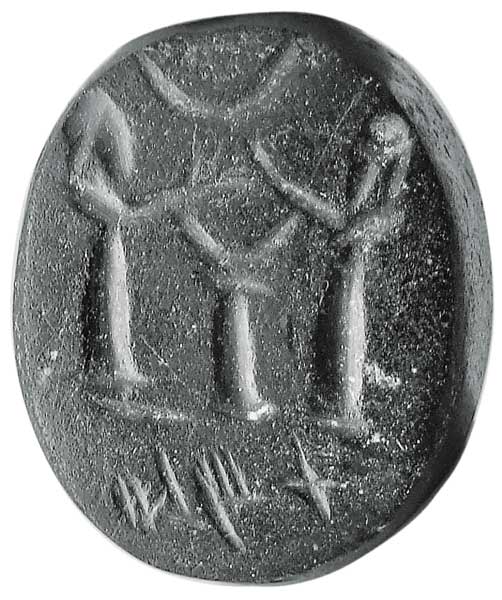

Once we had begun digging beneath the Northern Tower, we naturally decided to dig deeper, underneath the levels I have been discussing. Beneath the Persian period stratum, we found a stratum with pottery from a still-earlier period—from the Babylonian period (from 586 B.C.E., when the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem, to 538 B.C.E., when the Babylonians were defeated by the Persians) and perhaps extending into the early Persian period. This stratum produced some rather startling finds from the Babylonian period, including a scaraboid 032seal of stunning shiny black stone engraved with a cultic scene in Babylonian style. Two bearded men in long garments stand facing each other on opposite sides of an altar. Their hands are outstretched in a worshiping stance. Above them is a crescent moon, the symbol of the chief Babylonian god Sin. Beneath this scene is a short inscription consisting of three or four Hebrew letters.

In the first news release regarding this seal, I suggested that it was a three-letter name: Temah (

Despite the fact that seals are meant to be pressed into clay, some seals are nevertheless not written in mirror image—perhaps because they were engraved by a local craftsman who was not especially skilled. Another difficulty is the unclear “tail” of the lamed (

I suspect that this seal with its Babylonian scene was made in Babylon and that the name Shelomit was incised later, either in Babylon or in Judea. Names that appear on Hebrew seals usually include a family affiliation or title. Occasionally, however, only the name is engraved on the seal. Most of the latter type appear on seals that are also decorated on the surface. Such decorated seals, with names but no other identification, may well have been purely decorative objects not intended for actual or official use. If the seal was used simply for decoration, it would not necessarily have belonged to a woman who had administrative status. The name could refer to Shelomit, maidservant of Elnatan,3 or even Shelomit, the daughter of Zerubbabel, the heir to the throne of Judah (1 Chronicles 3:19).

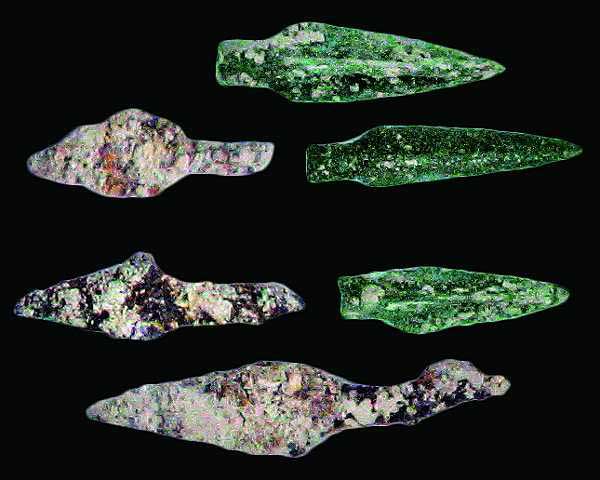

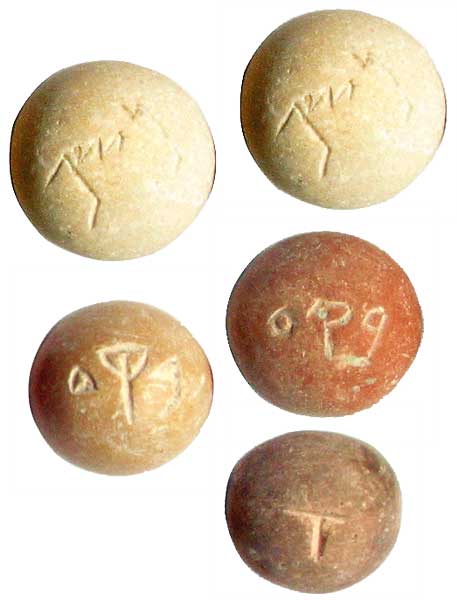

Beneath the stratum from the Babylonian period was a thick layer from the destruction at the end of the First Temple period (when the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem). Among the finds were pottery sherds, dozens of bronze and iron arrowheads, stone weights, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic clay figurines, and bullae (clay seal impressions). On one of the bullae found in the First Temple period layer, it was possible to clearly read the name Gedalyahu ben Pashḥur. This bulla was found only a few feet from the palace, where we had found another bulla during our first excavation season. That seal impression was only half an inch in diameter, but with beautifully preserved Hebrew letters forming the name “Yehuchal [sometimes written Yuchal [

How amazing these finds are! It is possible to understand how moving this is only when you hold a tiny mud bulla, only half an inch wide, and realize that it was rolling around for 2,594 years in the Babylonian destruction debris and was discovered still intact with the inscribed name still clearly legible. It is not very often that such a discovery happens to an archaeologist, in which a historical figure shakes off the dust of time and comes to life.

The Yehuchal bulla found in the palace is important not only for its Biblical name, but also because it provides one more archaeological confirmation that the palace continued to function as a royal administrative center until the end of the First Temple period, when it was no doubt destroyed by the Babylonians along with the rest of Jerusalem.

As noted above, Nehemiah’s description of the repair of the wall destroyed by the Babylonians refers to different sections assigned to various groups. One landmark is referred to as a tower projecting from “the Upper Palace [literally “House”] of the King” (Nehemiah 3:25; the Jewish Publication Society’s translation is garbled; see the Revised Standard Version and other English translations). If there was an “Upper Palace of the King,” there must have also been a “Lower Palace of the King.” Solomon had built his palace on the southern end of the Temple Mount, north of the City of David. The Lower Palace of the King must refer to King David’s earlier palace, which we have been excavating. The bullae of Yehuchal and Gedalyahu, which we found in the remains of the First Temple period, confirm that the palace remained in use after David’s time until the Babylonian destruction.

This is not the end of the story, however. As we continue to process the finds from the excavations, we look forward to giving BAR readers future updates.

All uncredited photos courtesy of the author.

Even before Nehemiah came from Babylonia to Jerusalem in the middle of the fifth century B.C.E., he knew that he wanted to rebuild the broken-down walls of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 1:3). When he arrived, he promptly made his famous night journey around the city, surveying the dilapidated city wall (Nehemiah 2:11–15). On the eastern slope, the wall of stones was so badly collapsed that his donkey could not navigate the path (Nehemiah 2:14). Quite amazingly, especially considering its condition, the wall was rebuilt in a mere 52 days (Nehemiah 6:15). Nehemiah was able to accomplish this feat by assigning different […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Eilat Mazar, “Excavate King David’s Palace!” BAR 23:01.

See Eilat Mazar, “Did I Find King David’s Palace?” BAR 32:01.

See Lawrence Stager, “Why Were Hundreds of Dogs Buried at Ashkelon?” BAR 17:03.

Endnotes

The precise date of the construction of the Southern Tower is still unclear. The foundations of the tower are built directly on top of houses from the First Temple period, but only additional excavations provide a more exact date.

Macalister and Duncan dated the tower to the Post-Exilic period, (fifth-fourth century B.C.E.). R.A.S. Macalister, Excavations on the Hill of Ophel, 1923–25 (London, 1926), p. 51. Kathleen Kenyon, who excavated here in 1962, and Yigal Shiloh who dug here in the 1980s, dated the tower, mistakenly in my view, to the Hasmonean period. Kenyon simply assumed that the tower belonged to the same fortification as the Southern Tower which she dated to that period (see K.M. Kenyon, Digging Up Jerusalem [London, 1974], pp. 191–192).

Shiloh based his dating on his excavation of a 3–4-meter-thick Hasmonean glacis on the Stepped Stone Structure. He assumed that the glacis of the Stepped Stone Structure belonged to the Hasmonean fortification of Jerusalem (The First Wall) along with the Northern and Southern Towers and the wall between them. (See Y. Shiloh, Excavations at the City of David, I, Qedem 19 (1984), pp. 20–21, Fig. 16.) However, the direct connection of the glacis with the fortification could not be conclusively proved since these areas were already excavated in the past.

Kenyon also dated a wall as part of Nehemiah’s reconstruction. But we have shown that the wall she identified is in fact the eastern external Wall 20 of the Large Stone Structure, which I suggest be identified with King David’s palace.