The Work of a Lifetime Destroyed—Three Years Later

012

Early in the afternoon of October 26, 1975 a fire struck the cramped, book-filled office of Father Albert Jamme at Catholic University in the nation’s capital. The fire probably started from neon tubes in a ceiling light fixture, but the exact cause is uncertain.

Father Jamme, who is the world’s leading South Arabian epigrapher, had kept in his office both his research library, the product of years of collecting, and his index file of over 100,000 South Arabian inscriptions. These inscriptions date from the 10th century B.C. to the 7th century A.D., when the South Arabian civilization was destroyed by invasion of Islamic forces.

When Father Jamme returned from lunch that fatal day he found his office filled with clouds of thick black smoke. Firemen rushed in to douse the flames and began throwing soggy books and papers out the window. Protective cellophane covers that had been carefully wrapped around rare photographs melted and then cooled into blocks of hardened plastic.

Father Jamme ran outside, only to find pieces of books draped in the trees and thousands of papers strewn in the mud or flapping in the fall wind. In a state of shock, he wandered through the soaked, half-burnt papers on the lawn while students quietly collected the scattered remnants (see photo).

The work of a lifetime had been destroyed.

BAR recently visited Father Jamme to see what had happened in the almost three years since the fire. Had he recovered from the enormous setback? The answer is a resounding “Yes” from this bouncy, determined 61-year-old scholar.

Dressed casually in a sport shirt and slacks, Father Jamme now works in the small musty administration building behind the library. Although a bit heavy-set, 013Father Jamme is gentle-looking. But a few minutes’ conversation quickly changes this impression. He is not only a scholar, but a fighter—disciplined, unafraid and tenacious. He clearly enjoys his work and is ready to debate the most minute point. He is a loner, but not lonely.

Since the fire, Father Jamme has spent most of his time reconstructing his library and inscription file. He borrows copies of rare books that were destroyed. Then he photostats each page, laboriously cutting and collating the pages and binding them into new books with cardboard covers. He estimates that he has now processed about 20,000 pages. He still has 50,000 to go. He is also reconstituting his 100,000-card index. If he keeps working at a constant rate, he expects to finish the reconstruction of his research library by 1982.

Doesn’t it get tedious? “When I was a boy back in Belgium,” he said, “and I had a task I didn’t want to do, my father would say ‘Never ask yourself whether you like it—just do it.’ And what else can you do? So I start every morning at six and work until five in the afternoon. After dinner I walk for two hours to relax.”

The fire did not destroy everything. Two cabinets of photographs were in another office at the time. The manuscript of a 245-page book had gone to the printer just eight days before. Students were able to soak the gluey masses of photo wrappers, then separate and dry the photographs, thus saving thousands of pictures. Enough index material was rescued to help make eventual reconstruction easier.

When you see this genial but determined man carefully cutting, pasting, and labelling, you know that he will certainly finish his monumental task.

Shortly after the fire, Father Jamme made the decision not to postpone a planned expedition to Yemen where he collects most of his inscriptions. A month after the fire, he left the comparative comfort of Washington, D.C. for the mountain wilderness of Southern Arabia.

His only companion on this expedition was a representative from the Yemen Department of Antiquities assigned to him in Sana’a, the capital. When asked if he resented being followed all the time, Father Jamme replied in his lightly accented English, “Excuse me. I demanded the representative. I want the government to know exactly what I am doing at all times. Then we won’t have any problems.”

Father Jamme recalled a trip to Yemen 25 years earlier. In 1951 he was part of an ill-fated attempt to excavate at Marib, home of the legendary Queen of Sheba. It was the first expedition allowed into northern Yemen (now the Yemen Arab Republic). Hostile natives harassed the team and Father Jamme was kept a virtual prisoner for 28 days because he refused to surrender his squeezes to the local government. In the end, the entire expedition had to flee for their lives, leaving their squeezes and equipment behind. (A fascinating account of this expedition can be found in Qataban and Sheba by Wendell Phillips, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1955.)

Things were much better in 1975. In Sana’a, Jamme rented a truck and drove to Marib—where 25 016years earlier, he had also searched for inscriptions. This time he stayed in a government-owned guest house. Each day he would drive into the mountains looking for inscriptions.

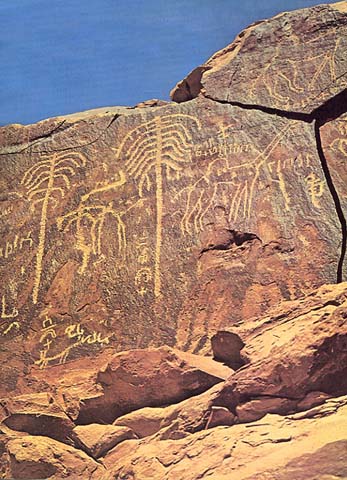

Unlike the Israelites who wrote most of their inscriptions on pottery, the South Arabians carved on stone. These ancient Arab nomads could not carry bulky clay pots around with them. Even today, the Bedouins carry most of their provisions in goatskins.

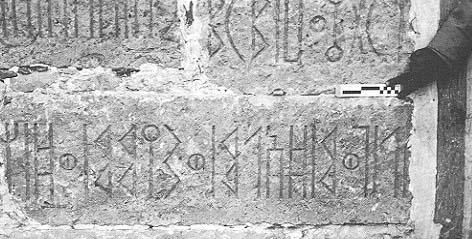

Father Jamme explained that epigraphers divide South Arabian stone inscriptions into two categories: formal inscriptions, using a monumental alphabet of block letters which were usually carved by professional engravers; and graffiti (singular: graffito), which were carved in a cursive script by non-professionals and are often accompanied by pictures.

In the old days inscriptions were copied by “squeezing” or pounding wet blotting paper into incised letters, waiting till it dried and then removing it. Hence, the term “squeeze”. Today a thin layer of rubber latex or liquid plastic is usually painted over the inscription. This is then covered with cloth and allowed to dry. Two additional layers of rubber or plastic or another layer of cloth are then added. When all the layers are dry, the squeeze is peeled off. It has the texture of a heavy Halloween mask. Latex squeezes can be rolled up for easy storage and are especially convenient for copying long inscriptions.

In 1975–1976, Jamme stayed three months in Yemen. By late February, 1976, he was exhausted from his daily treks into the mountains around Marib. Shortly after the new year, he had taken a bad fall. Besides, a throbbing toothache was pounding in his head. One day he returned to Marib but did not have the strength to get out of his truck unassisted. That night he developed severe dysentery. Father Jamme knew he would be unable to drive back to Sana’a. Fortunately, a plane was leaving for the capital the next morning. He left his rented truck in Marib and boarded the plane. By the time he landed at Sana’a he felt numb. In Sana’a, a Peace Corps friend who was a nurse immediately recognized that Jamme was suffering from a serious blood infection. “He saved my life,” recalls Father Jamme. After massive doses of antibiotics, the patient recovered, but he had lost 35 pounds. As soon as his fever subsided, Father Jamme walked several miles to a dentist to have his aching tooth extracted. “Well,” he commented, “I was in the underground during the war, so we learned to be tough.”

In all his travels through South Arabia, Father Jamme has found no written reference to the fabulously wealthy Queen of Sheba who supposedly came to visit King Solomon around 950 B.C.

According to Professor Jamme, women had much higher social status in early South Arabian society than they do in Yemen today. Women often served as tribal chieftains, although they were probably not permitted to become overall rulers of a region. Jamme speculates that the so-called Queen of Sheba was probably the leader of a tribe called Saba (Sheba in the Bible) during the first phase of the Sabaean kingdom, whose capital was Marib. Because she was an exotic visitor to Solomon’s court and the leader of her group, the Hebrew scribes called her a queen when, in fact, she was not royalty in her own country.

Early in the afternoon of October 26, 1975 a fire struck the cramped, book-filled office of Father Albert Jamme at Catholic University in the nation’s capital. The fire probably started from neon tubes in a ceiling light fixture, but the exact cause is uncertain.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username