Understanding the Nabateans

026

027

028

In 312 B.C. a Greek diplomat and historian named Hieronymus of Cardia visited the Dead Sea and probably the Negev and reported:a

“There are many Arabian tribes who use the desert as pasture, [but] the Nabateans far surpass the others in wealth, although they are not much more than 10,000 in number.”

Masters of the desert, the Nabateans were the dominant traders, merchants and caravan guides for centuries. The principal factor that accounts for the Nabatean superiority was their unrivaled ability to procure water in the desert. Hieronymus describes this in detail. In modern terms, the Nabateans transformed concentric nomadism into linear nomadism. The traditional wanderings of ancient nomadic tribes centered around the few permanent natural sources of water—the oases in the desert. The Nabateans, however, learned to line their cisterns with impermeable plaster. These desert cisterns were then filled with water from the occasional rains. In this way, they were able to store water for a year or more. The Nabateans could thus cross the inhospitable deserts of northern Arabia, the Negev and Sinai, finally reaching the harbors of the eastern Mediterranean, where, Hieronymus tells us, they brought caravan loads of spices and aromatics from Arabia.

Indeed, NBTW, the consonantal spelling of the name by which the Nabateans later became known both to their neighbors as well as to Greek and Roman historians, means, according to classical Arabic lexicographers, “to dig for water” (as a verb) and “a man who digs for water” (as a noun). In later Arabic, the same noun changed its meaning to denote “a farmer,” “a man who tills the land,” “a lowly creature,” reflecting the change in Nabatean fortunes, as we shall presently see.

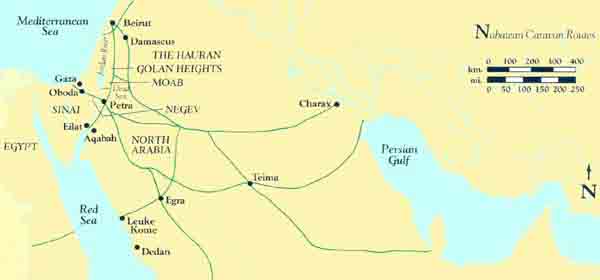

For centuries, however, from about the sixth century B.C., or even earlier, to about the middle of the first century A.D., the Nabateans and their allies held a monopoly on the lucrative spice trade. Some of these precious commodities, such as myrrh and frankincense, were indigenous to Arabia, but others originated in India and even in the Far East. Cinnamon, for instance, used since Biblical times, grew only in southeast Asia and China. The spices were brought from southern Arabia to ’El ‘Ulab in northern Arabia. From there, Nabatean merchants took over and were responsible for their transportation to harbors on the southeastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea.

Hieronymus tells us:

“It was [the Nabatean] custom neither to sow grain, plant fruit-bearing trees, use wine, nor construct any house; if anyone is found acting contrary to this, death is his penalty.”

This behavioral pattern was by no means unique in Biblical times. When the prophet Jeremiah brought some Rechabites to the Temple and offered them wine, they replied:

“We will not drink wine, for our ancestor, Jonadab son of Rechab, commanded us: ‘You shall never drink wine, either you or your children. Nor shall you build houses or sow fields or plant vineyards, nor shall you own such things; but you shall live in tents all your days, so that you may live long upon the land where you sojourn.’ And we have obeyed our ancestor Jonadab son of Rechab in all that he commanded us” (Jeremiah 35:6–8).

While Hieronymus’s description of the Nabateans was accurate for their early, formative years, when he lived, things began to change about the middle of the first century B.C., after the arrival of the Romans in the East.

With Egypt already in their domain, the Romans turned to Arabia. In 25 B.C., they attacked with the half-hearted help of 1,000 Nabatean camel riders headed by Sylaios, the Nabatean prime minister, who served as chief guide to the campaign. They were also assisted, incidentally, by 500 soldiers supplied by Herod the Great. With this “triple” army, “Blessed Arabia” was stormed—apparently unsuccessfully. According to the Greek historian Strabo, who was in Egypt at the time, Augustus Caesar “sought to win the Arabians over to himself or to subjugate them—for he expected either to deal with wealthy friends or to master wealthy enemies.” But neither of these objectives was achieved. Both the Romans and the Nabateans attended to business as usual for the next half century or so. For the Nabateans this was a period of great prosperity, and the Romans were looking for ways of getting a greater share 029of that prosperity.

From the beginning of the last quarter of the first century B.C., the Nabateans established a well-organized system of caravan stops along the routes running from Egra (about 250 miles southeast of Eilat in modern Saudi Arabia) to Petra and Damascus in the northeast, and to the Negev, Sinai and the Mediterranean coast in the northwest.

By no means have all of these caravan stops been archaeologically investigated, but the cumulative evidence of a number of them indicates that a major caravan stop contained a temple, which, in addition to offering regular religious services, served as a bank. Deposits could be made at one temple and withdrawn elsewhere. This avoided the necessity of carrying large amounts of silver, which was required for the payment of merchandise or for services and fees. Near the temple was usually a bath house where weary caravaners could refresh themselves.

In order to protect the caravans in areas infested with highway robbers (who, incidentally, were also Nabateans), merchant Nabateans created an intricate military system, with military camps at central points, as well as forts and watchtowers along the roads.

To provide a proper burial for people who died on the road, the Nabateans established burial grounds at their major caravan stops, often filled with large funerary monuments.

Installations for breeding camels, used both as beasts of burden and for riding because they were the only animals capable of traversing the desert, were also part of the typical Nabatean caravan stop. These caravan stops also included numerous pens for herds of sheep and goats, a major source of food for merchants and travelers. And, of course, a network of cisterns, both in the caravansaries and along the roads, were a necessity.

The attendants at caravan stops and the caravaners 031themselves lived in tents. Only at a later phase in Nabatean history were stone houses constructed. But the caravan stops we are describing date from about 30 B.C. to 50 or 70 A.D. (the Middle Nabatean Period).

To complete the picture during this period when the Nabateans dominated the lucrative spice trade in northern Arabia, they also had several large administrative centers and a number of small, minor ones. Among the large centers were Egra, already referred to; Tayma, another important oasis; and Leuce Kome (the “White Village,” Hawara in Nabatean), the Nabatean harbor on the eastern shore of the Gulf of Eilat.

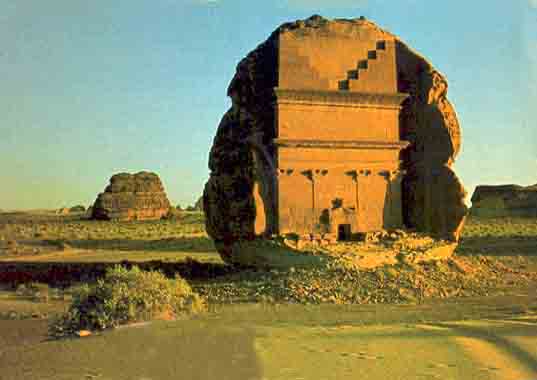

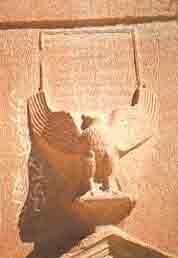

At Egra, only the burial ground has been intensively investigated. Adjacent to the springs of the oasis that water the stately palm trees is a moonscape strewn with sandstone rocks. From the layered rock faces, funerary monuments were sculpted. On the facades of 30 of these monuments, detailed funerary inscriptions were engraved. The funerary monuments vary from simple tombs decorated at the top with crenelations and steps, to richly adorned monuments containing Egyptian, Greco-Roman and Nabatean decorative elements, often intermingled.

The inscriptions are copies of legal documents. They specify the name of the owner of the monument; a list of people who, together with their descendants, are legally entitled to be buried in the monument; warnings against unauthorized sale or lease of burial rights; curses against those who illegally obtain burial rights; a provision for fines to be paid to certain temple treasuries, to the king’s treasury, or to the treasury of the local strategos; the date when the monument was cut (by regnal years of the ruling Nabatean king); and the name of the sculptor or sculptors who made the monument.

These inscriptions provide us with an enormous amount of information. From the personal names, we learn that the simpler monuments belonged to women. The larger and more richly decorated monuments belonged to male professionals. Among the military, we learn of a centurion, a chiliarchos, strategoi, hipparchoi, and an augur. Also recorded are the names of people identified as a military (?) physician, and a banker (that is, a money changer). The names of the commercial nobility can be recognized easily because they contain a three-name-pedigree—for example, “‘Aidu son of Kohaylu son of Elkassi,’” or “Hushabu son of Nafiyu son of ‘Alkuf.” Persons of the better Semitic families were in the habit of recording the names of their ancestors. The Nabateans usually limited the number of ancestors to two, rarely more; among the Safaitic-Thamudic Arab tribes, the mention of six or seven ancestors is not unusual. In a few cases at Egra, we are told where the person comes from (a woman, we are told, is from Tayma). In one case, ethnic origin—a Jew—is given.

From the personal names of the sculptors, we learn that there were guilds of sculptors, perhaps under royal patronage, as the names of some imply. Some of the sculptors’ names contain the elements ‘abd’, meaning “servant,” plus a dynastic name, like ‘Abdharethat, or ‘Abd‘abdat. These elements are also present in the names of military personnel; they were no doubt added to the person’s given name when he joined a particular group of artisans, or assumed a particular military office.

Near the funerary monuments at Egra, small cult niches were cut into the rock, most of the time in a shady place where commemorative services could be held and funerary meals eaten.

032

Although there must have been temples and military installations at Egra, they have not yet been discovered.

The Nabateans seem to have used writing almost exclusively for religious purposes—I will comment on the significance of this fact later. Because of the lack of any historical documents intended as such, the funerary inscriptions are doubly important. They are also important because they are frequently dated by the regnal years of kings, which can be translated into fixed historical dates. Two-thirds of the funerary monuments at Egra were cut during the reign of King Aretas IV (9 B.C.–40 A.D.). The remaining third—mostly simpler monuments—were made during the reign of Malichus II (40–70 A.D.) and during the first five regnal years of Rabel II (70–106 A.D.). (In 106 A.D. the Romans annexed the Nabatean kingdom to the Roman empire and created the new province, Provincia Arabia.)

Although we find the names of a number of high-ranking officers in the Nabatean army at Egra (and, as we learn from inscriptions found on the roads leading to Egra, even members of the general staff) all of these references to a military presence at Egra date after about 25 A.D. I believe that this sudden arrival at Egra 033of a major part of the Nabatean army, as these inscriptions reflect, can be accounted for by the gradual loss of the spice trade and the ensuing economic decline, which in turn opened the way for other Arabian tribes to intrude into the area. The Nabateans struggled unsuccessfully to arrest these intrusions. Further decline is reflected in the fact that no funerary monuments at Egra can be dated after 75 A.D.

Between Egra and Petra there are several smaller caravan stops. The best known is Er-Ram, northeast of Aqabah. Here investigators have located a Nabatean temple, military installations, an intricate water supply system, and a cemetery, but only the temple has been examined in detail.

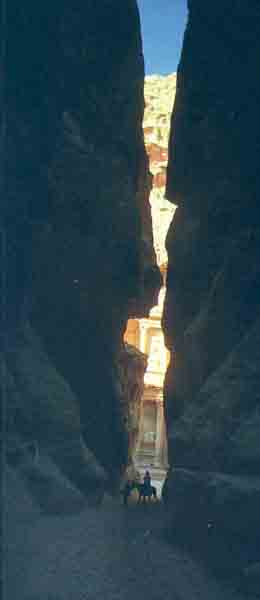

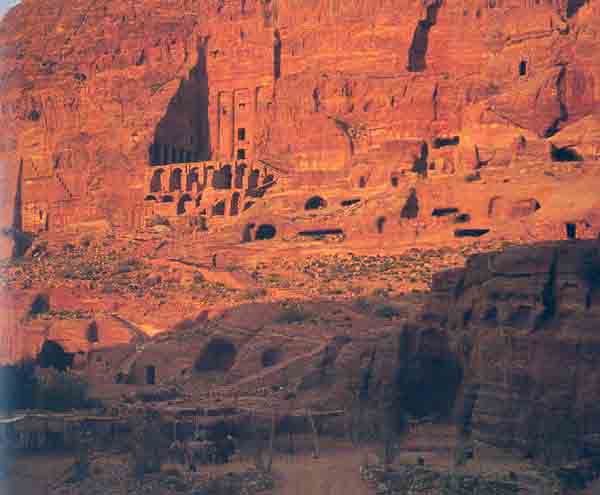

Ever since its discovery in 1812, Petra has attracted enormous attention from scholars as well as from tourists. Without belittling the importance of this extraordinary site for the study of Nabatean culture, the excessive, sometimes almost exclusive, emphasis on Petra has done injustice to the recognition of Nabatean culture in general.

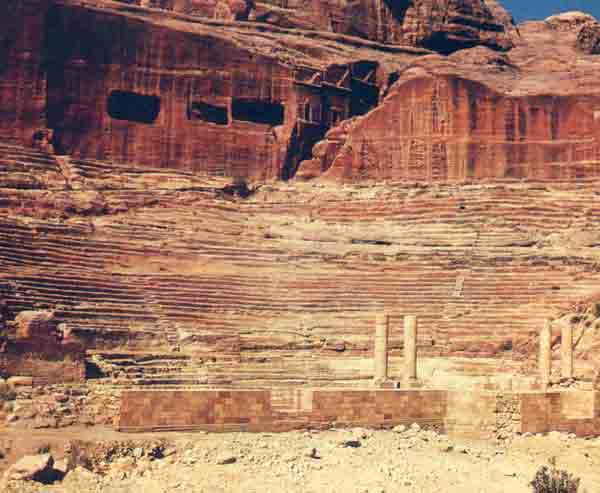

It is a fact that Petra lies off the major Nabatean trade routes. Economically, therefore, it is of minor importance. In my view Petra was the major religious center of the entire Nabatean Kingdom, housing its most important temples, high places and huge cemeteries. The other installations found there—the theaters, a bath house, etc.—were all built to serve this enormous religious center.

Although I am among the minority of scholars, I do not believe that Petra was ever a city as such, built on the pattern of western Greco-Roman cities. True, a “town plan” of Petra, drawn by a German team of scholars during World War I, shows a cardo (the main street in a Roman city) with a triumphal arch, two theaters, two nymphea, three markets, a palace, a 034gymnasium, as well as a temple.c These scholars interpreted their plan as a Hellenistic-style metropolis. In this, I believe they erred. We do not know where the Nabatean kings resided. But there is no evidence that it was at Petra. Theaters were an integral part of most Nabatean temples. They were not for popular assemblies and plays, as the excavator of the great theater at Petra believes, but most probably for funerary rites—possibly for the funeral of King Aretas IV, if the famous nearby funerary monument, known popularly as the Treasury of the Pharaoh (Khaznet Firaun), was his tomb. Funerary meals were also an integral part of these rites; only in this way can we explain the mountains of broken pottery that have been found at Petra. No markets have as yet been discovered at Petra. The monumental street and gate are not a cardo in the Roman sense of the word, but rather a sacred way leading to the main temple. No palace has been found at Petra.

If Petra had been a regular metropolis, it would have contained at least a thousand dwellings. (Some scholars have estimated that Petra was home to 40,000–50,000 inhabitants.) Despite extensive excavations at Petra, not enough dwellings have been discovered even to accommodate the temple and burial ground attendants.

The chronology of Petra is difficult to pin down. In my view, taking into account all we know of Nabatean history, no monuments at Petra predate 50 B.C., and 035there is little likelihood that many monuments were made after the end of the first century A.D.

This brief description of the Nabateans and their culture relates to the high point in their history, the Middle Nabatean Period (c. 30 B.C.–c. 50–70 A.D.). Let us now look at what we can discover of their origins in the Early Nabatean Period (fourth century B.C. or earlier to the beginning of the first century B.C.) and at what happened to them after their floruit—in the Late Nabatean Period (end of the first century A.D. to the second/third century A.D.).d

As the quotation from Hieronymus of Cardia, cited above, indicates, the Nabateans were to be found along with other Arabian tribes as early as the late fourth century B.C. (Hieronymus wrote in 312 B.C.).

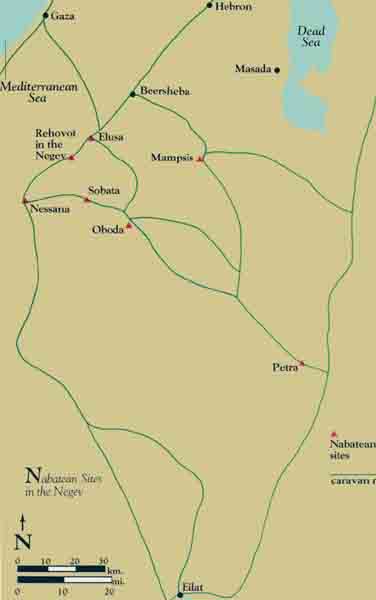

By the Middle Nabatean Period, three important caravan centers that might give a clue to earlier Nabatean life had been established in the central Negev highlands: at Oboda (this is the original Nabatean form of the name; in modern Israel, it is known as Avdat), linking the central Negev with northern Arabia and Edom; at Nessana on the west, which led to Sinai and the harbors at the southeastern end of the Mediterranean; and at Elusa, which apparently was the center of the system, from which roads went up to Beer-Sheva and Jerusalem on the northeast, and to Gaza on the northwest. These three Negev sites formed a triangle with its apex at Elusa.

The question is: How much earlier were these sites established as Nabatean settlements? At Elusa, investigators found a dedicatory inscription (dating to c. 168 B.C.) to King Aretas, the first Nabatean king. Whether the other Negev sites were occupied as early as Elusa still needs further study. Recently, a hearth was found at Oboda with pottery of the fourth and third centuries B.C.e This site was apparently an encampment of nomads before it was a major Nabatean caravan stop. But it is difficult to say much more. The presence of Nabateans in the central Negev during the fourth to first centuries B.C. still needs substantiation.

In the Middle Nabatean Period, these three Negev sites formed the backbone of the Nabatean caravan system in the central Negev. On the plateau of Oboda, almost 2,000 feet above sea level, a magnificent temple was built of hard white limestone. Originally built in the last quarter of the first century B.C.—in the lifetime of Obodas II (30–9 B.C.)—only the huge podium and the system of gates leading to it have been preserved to any major extent. Most of the beautifully drafted and decorated building blocks were used later, in the Byzantine period, in the construction of two Christian churches. This temple was renovated in the third century A.D., at which time the now-deified King Obodas, identified as Zeus, and the Nabatean goddess Allat, now in the guise of Aphrodite, were venerated.

Oboda also served as the main Nabatean military stronghold in the Negev, housing its camel-riding soldiers who manned the forts and guarded the roads. To accommodate these troops and their camels, a square camp, 300 feet on each side, was built at the northern end of the plateau. On the southern end were large sheds for breeding camels, as well as sheep and goats, a principal source of both meat and milk. A potter’s workshop, east of the temple, supplied pottery for the temple, the army and the local population. Here the famous, thin Nabatean pottery, with its unique painted designs, was produced. Temple attendants and people attending to the needs of the caravaners, in addition to the caravaners themselves, stayed in an encampment east of the military camp.

The site of Nessana is, at the moment, not as impressive as Oboda. It was excavated in 1935–37 by an Anglo-American team, and it is now being re-escavated by a team from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. However, the site does boast a magnificent staircase that leads to the acropolis. According to the most recent excavations, this staircase rests on a fill that dates to the late first century B.C. 036at the latest. It probably led to a Nabatean temple built, of course, after this date.

The third Negev site, Elusa, was discovered and identified by Edward Robinson in 1838. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many stones from the site were used for the construction of buildings in Gaza and Beer-Sheva. A detailed survey was conducted in 1973, and two short seasons of excavations were carried out by a team from Hebrew University in 1979 and 1980 (the later season in collaboration with Mississippi State University). These brief excavations proved beyond doubt that a Nabatean (and later) town lies safely buried under a thick cover of sand and dust. A Nabatean theater was discovered, identified by the pottery found in the fill and by two typically Nabatean capitals that decorated the main entrance to the stage. As we have seen at Petra and elsewhere, a Nabatean theater is connected either with a temple or with a cemetery. Indeed, a mausoleum, possibly Nabatean, and a cemetery, reused by Bedouin in later periods, were found in close proximity to the theater at Elusa. Near the theater, a Christian church was found, the spacious atrium of which may overlie a Nabatean temple.

While Oboda, Nessana and Elusa formed the framework of the Nabatean caravan system in the Negev during the Middle Nabatean Period, several smaller sites filled in the gap. These included Mampsis (Mamshit), Sobata (this is the original Nabatean form of the name; in modern Israel, it is known as Shivta) and Rehovot ba-Negev. The system was completed with numerous small road-stations, military installations and watering places.

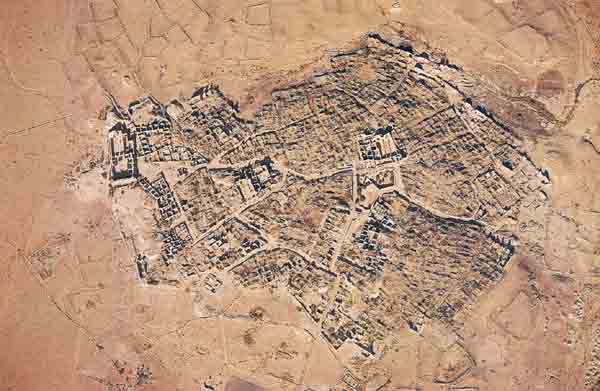

In the Late Nabatean Period (late first and second centuries A.D.), large caravansaries grew into towns. 037The best known of these is the town of Mampsis.f The new town at Mampsis was on a completely different plan from the old caravansary, with its public buildings. The new town was built to the requirements of farmers. The old caravansary was built on an open plan with great distances between buildings. The new town had dwellings crowding up against one another. This pattern has been found at a number of sites. The Nabatean town of the Late Nabatean Period can be easily spotted from the air: In contrast to the openness of the large caravansaries of the Middle Nabatean Period, the towns of the Late Nabatean Period form a coagulated spot with lines of streets. The spot marking the town is darker than the surrounding terrain and is created by the rather thickly built town.

The reader will remember that according to Hieronymus, writing in 312 B.C., the Nabateans did not “sow grain, plant fruit-bearing trees, use wine, nor construct any house.” The penalty for transgression was death. But this was in 312 B.C. By the end of the first century A.D., things had changed. The Romans conquered the Near East by the middle of the first century B.C. They were determined to wrest from the Nabateans the enormously profitable Arabian trade routes. The Romans successfully displaced the Nabateans by the middle of the first century A.D. The immediate effect on the Nabateans and on the allied tribes must have been devastating. The desperate members of the other Arabian tribes, who most probably shared in the prosperity of the previous centuries, were now deprived of their livelihood. They stormed the now vulnerable Nabatean centers after devastating the old caravansaries.

So the Nabateans turned to agriculture and settled in towns.

Very early they seem to have begun to breed horses, apparently of the pedigree that later became known as the Arabian horse. The Nabateans sold these horses to 039hippodromes all over the neighboring Roman provinces. Barley is the principal food of this horse—it is a seasonal crop, and even Bedouin grew it. So the Nabateans started to grow barley. This probably led to their planting other crops. Then they began to plant trees, and, as befitting farmers, they built permanent stone dwellings for themselves.

Agriculture of course requires water. The skill with which the Nabateans had earlier collected water for drinking and bathing was now used to collect water for irrigating fields. They did this by terracing narrow valleys and irrigating them with rainwater streaming from hillsides where they had cut long channels.

Consider the situation at Mampsis. The Nabateans solved the problem by a means used in South Arabia for generations: building dams to collect the water from the few torrential rains in winter. The wadi (the usually dry riverbed) as it approaches Mampsis is a wide, slow stream, deepening to a steep, rocky canyon just east of the town. In the shallow part of the wadi, the Nabateans built three enormous dams. The largest is 35 feet high, nearly 180 feet long, and 25 feet thick at the top. The pools formed by these dams had a capacity of 13,000 cubic yards. The water was transported from these pools into numerous cisterns excavated in houses, courts, and squares of Mampsis, and to a large public pool that fed a Roman-style bathouse. This same pattern was repeated at other Nabatean towns.

In short, the traders and highway robbers became farmers. Whereas previously the only houses they built were for the gods (temples) and the dead (tombs), now they built houses for themselves, abandoning all forms of nomadism and replacing their tents with permanent dwellings.

For us, the descendants of a rural society, the change from a tent to a house might appear to be an improvement, a change that provides better living conditions. But does it really? Look at it from the viewpoint of the nomad settling down. Tents are spacious. Tent dwellers easily allocate a special tent for almost every function in their social life: a tent for the men, another for women, children, guests, storage space, etc. Moreover, by moving the tent seasonally, problems of pollution are readily solved—in the best way known 043to the ancient world.

The change from the freedom of the tent to the limitations of the house must have been viewed by the Nabateans as revolutionary. At Mampsis, they overcame these obstacles by planning extremely large dwellings. The excavated houses extend over 800, 1,200 and even 2,100 square yards. Compared to Greek and Roman town planning, Mampsis is hardly a planned town. Wide streets and empty squares separate the houses to provide for maximum privacy.

There is always a tendency among scholars to look at the unique aspects of the particular culture or phenomenon to which, often, they have devoted their professional lives. Because their knowledge is naturally concentrated in one area, they often tend to examine their subject in isolation, rather than seeing it as part of a larger canvas.

This is no less true of Nabatean studies than of studies of other cultures. And perhaps this is—or was—true of my own work in the field of Nabatean studies. Since 1967, however, I have been studying Nabatean personal names; and in 1985–86 I spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, as a result of which I am increasingly led to see Nabatean culture and its characteristics as part of a much wider one, embracing a large number of Arab tribes.

One of the factors that led to a flawed understanding of the content of Nabatean culture was that the Nabateans used an Aramaic script and language, while other contemporaneous Arab tribes used a South Arabic script and an Arabic language (Safaitic and Thamudic).

Add to this the differences in the material culture of the Nabateans, on the one hand, and of other tribes in the area the Nabateans inhabited, on the other, and the result was that scholars pursued two quite different lines of study in attempting to understand what they considered separate groups. Different fields of study developed and became the province of different scholars. Some mastered the Nabatean-Aramaic script-language-culture; others mastered Safaitic-Thamudic Arabic script-language-culture. Few scholars felt comfortable with both Nabatean-Aramaic and Safaitic-Thamudic Arabic.

In my study of personal names, however, I have learned that the lines of demarcation are not so clear. My initial effort in studying Nabatean personal names was to try to subdivide them into smaller, perhaps tribal, divisions. It turned out that they could be subdivided on a geographical basis. Based on differences in personal names, four geographical regions could be identified in which the Nabatean-Aramaic script was used: northern Arabia, Sinai-Negev, Edom-Moab (east of the Jordan River) and the Hauran (the area of northeastern Jordan and southeastern Syria, adjoining the Golan Heights). In each of these regions, indigenous personal names developed. But then, to my great surprise, I discovered that the Nabateans were not the only ones who used the supposedly Nabatean-Aramaic script and language. In the ruins of the main temple at Seeia, in the northern Hauran, numerous inscriptions were found; some are in Greek and others in the language we refer to as Nabatean-Aramaic. Similar inscriptions were found also in other towns and villages in the Hauran. Many of these are dated by regnal years of Nabatean kings, but the tribe mentioned in these inscriptions is the ‘Ubaishat (or Obaisenoi, as they are called in the Greek inscriptions). The ‘Ubaishat, although they used the same Aramaic language as did the Nabateans, did not belong to the Nabatu (Nabateans); rather they belonged to the Safaitic-Thamudic group of tribes.

Next, I studied temples in the Hauran that everyone thought were built by the Nabateans, but which were in fact built by the ‘Ubaishat.

We now have evidence that in Sinai too the so-called Nabatean script and language were used by another tribe or tribes. The evidence is somewhat complicated. Some of the Nabatean-Aramaic inscriptions in Sinai identify deities. Many other inscriptions in southern Sinai contain personal names with theophoric elements (names of deities) embedded in them. These theophoric elements supplement our knowledge of the deities they venerated. An analysis of these deities indicates that in Sinai some deities were venerated that were not worshipped in other parts of the Nabatean realm; conversely, deities worshipped elsewhere in the Nabatean realm have not been found in Sinai. This suggests that the tribes in Sinai belonged to other, non-Nabatean groups, and not to what we call Nabateans.

We now have roughly 15,000 Safaitic-Thamudic inscriptions (written in a South Arabian script) and about 5,000 Nabatean inscriptions (written in an Aramaic script). Most of these inscriptions have been found carved in the rock. Among the Nabatean inscriptions are about 1,260 personal names, some of which are Greek, Roman, Edomite and other non-Arabic personal names. But the important point is that the remaining large majority, which are Nabatean, fit very well into the much larger Safaitic-Thamudic group of personal names which number more than 6,200.g

Another peculiarity about Nabatean inscriptions has impressed me almost from the beginning. As I noted earlier, almost all Nabatean inscriptions are of a religious character—funerary inscriptions, dedications of temples and high-places, inscriptions associated with votive niches, invocations of pilgrims, etc. This seemed unnatural, yet I had no good explanation for this peculiarity. During my stay at the Institute for 044Advanced Study, I decided to examine the content of the Thamudic-Safaitic inscriptions. To my astonishment I found that what seemed to be lacking in the Aramaic-Nabatean inscriptions was to be found in the Thamudic-Safaitic inscriptions, although the latter also include funerary inscriptions and incantations. But Thamudic-Safaitic inscriptions also express simple statements of ownership—of both objects and animals. They deal with matters of love and hate and war—indeed with all aspects of human life. We read of a man who “loves the mouth” of another man. One Thamudic inscription reads: “This is Baddan. He is lovesick.” Another reads: “This is Shazat, an old man, and he (still) hugged (and) kissed.” On the other hand, if we were to judge the Nabateans by their inscriptions alone, we would conclude that they were a holy nation, a kingdom of priests.

Nor does the corpus of Nabatean inscriptions contain any historical literature. We can learn almost nothing about Nabatean history from this corpus. (What we do know comes from later Greek and Latin sources.)h Strangely enough, however, the Safaitic-Thamudic corpus does refer to Nabatean wars and Nabatean kings. From the Safaitic-Thamudic inscriptions, we hear of the Nabatean kings Aretas, Obodas, Rabel and hmlk. Two separate references in Safaitic-Thamudic inscriptions tell us that certain events occurred in the year “hmlk died.” Scholars have long puzzled as to who hmlk was. But now that we have identified three Nabatean kings in Safaitic-Thamudic inscriptions, it seems clear that the mystery king is a fourth Nabatean king, Malichus (or Maliku in Nabatean-Aramaic). This hmlk-Maliku is either Malichus I, who ruled from 60 to 30 B.C., or Malichus II, as I tend to believe, who ruled from 40 to 70 A.D.

The study of the relationship between the Nabateans and other Arabian tribes is likely to be a major focus of the next generation of scholars. Provisionally, we may conclude that other Arabian tribes like the ‘Ubaishat 045must have participated with the Nabateans in the great economic revolutions in their history. In short, the Nabateans were part of a great family of Arab tribes, all of whom they surpassed despite their small numbers. Once the Nabateans learned how to overcome the shortage of water in desert areas, they spread from northern Arabia to Edom, southern Moab, the Negev, Sinai and even into a small section of Egypt, establishing a network of caravan routes. At the same time, or perhaps somewhat later, other Arab tribes emerged from the darkness, foremost of whom were the ‘Ubaishat, who conquered the Hauran and adjoining regions. For some reason, Aramaic script was used to express matters relating to religion, Arabic for other matters. By the second half of the first century B.C., due to contacts with other civilizations, they began to deviate from their ancestral ways. Gods assumed human form—as in Greek religion. Houses were built. The desert dwellers began to settle down, ultimately becoming farmers.

Let me conclude by telling you about an extraordinary inscription, found only in 1979 and first published in 1986,i which nicely illustrates some of the points I have been making.

The inscription was found accidentally by Mathie Koones of Ben-Gurion University’s Institute for Desert Research, maintained at Kibbutz Sde Boker, the kibbutz where David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first and most famous Prime Minister, spent his last years. The inscription itself was found on a low, flat rock about three miles north of Oboda, just above the deep gorge of Ein Avdat with its spectacular series of steep waterfalls.

The inscription consists of six lines engraved with a flat tool, perhaps made of flint. The script is the Nabatean-Aramaic we customarily find at Nabatean sites. As to the language, more later.

The inscription first blesses the reader who stands before the god Obodas (apparently a statue), then seeks a blessing on one Garm’alahi who set up the statue. Then comes a kind of protestation that Garm’alahi acted neither for benefit, nor favor (presumably in setting up the statue). The inscription goes on: If death comes, let it not claim Garm’alahi; if affliction comes, let it not seek out Garm’alahi or his family. The inscription ends with a simple statement that Garm’alahi wrote the inscription with his own hand.

I must tell you that despite my more than 20 years studying Nabatean inscriptions at the time I first saw this inscription, this one proved to be a brain-buster—or at least part of it was.

The first three lines were comparatively easy: May the reader and Garm’alahi who put up the statue be remembered for good. The last line was also easy. Garm’alahi himself wrote the inscription.

It was the fourth and fifth lines that proved difficult. I thought I could make out the letters—in the same Aramaic-Nabatean script I was accustomed to, but I couldn’t understand the sense of these two lines. In despair I went for help to Professor Joseph Naveh of Hebrew University, who is better trained than I in reading Nabatean-Aramaic script. Naveh too read the letters in these two lines, but could not fully grasp their meaning. He suggested that they might be Arabic, so he called in an Arabist, Professor Shaul Shaked.

It turned out that these two lines are indeed Arabic!

Thus, the translation offered is the fruit of a joint effort by three scholars. This decipherment confirmed that the Nabateans formed an integral part of the Arab world. Previously we had only Arabic words and phrases in Nabatean inscriptions. But here are two lines of pure Arabic in an otherwise Nabatean inscription.

Other Nabatean inscriptions from Oboda date from 7 B.C. to 125 A.D. Our inscription probably dates to the end of this period, but surely no later than 150 A.D., when Nabatean-Aramaic script went out of use, with Greek replacing it. This makes our inscription the earliest known Arabic inscription of any length. The next earliest Arabic inscription of any length was found at en-Namara (southeast of Damascus) and dates to 328 A.D.

We know from literary sources and from epigraphic finds that the Nabatean King Obodas was deified after his death. According to one Greek source, he was buried at Oboda. His cult has left many traces at Oboda, the city named for him.

Statues of Nabatean kings were probably very rare, especially of deified ones. Statues of gods were no doubt the then-recent result of powerful Greek influences. Nabatean gods had been commonly symbolized by simple stone pillars, as was the custom among ancient Semites. But the statue that Garm’alahi put up had the likeness of a human being. This may well have been an unpardonable offense. Garm’alahi knew enough Aramaic words to describe his act, using the formula (“remembered be for good”) customarily used in dedications of tombs and temples. He could not find, however, in his restricted Nabatean-Aramaic vocabulary, expressions suitable to protect himself against any impending calamity that his deed might cause. Apparently for this reason, he turned to his much richer mother tongue, Arabic.

The Obodas inscription was found north of the city of Oboda, at the border of Oboda’s extensive area of cultivation. The Nabateans of Oboda had already become farmers. This is helpful in dating the inscription, because Nabatean agriculture did not begin at Oboda until about 75 A.D.

Thus, the ancient Nabatean taboos noted by Hieronymus—sowing grain, planting fruit trees, using wine, constructing houses—were, one by one, broken down. Only with the advent of Christianity, however, was the last of the four ancient taboos mentioned by Hieronymus—the cultivation of the wine grape—abandoned.

028 In 312 B.C. a Greek diplomat and historian named Hieronymus of Cardia visited the Dead Sea and probably the Negev and reported:a “There are many Arabian tribes who use the desert as pasture, [but] the Nabateans far surpass the others in wealth, although they are not much more than 10,000 in number.” Masters of the desert, the Nabateans were the dominant traders, merchants and caravan guides for centuries. The principal factor that accounts for the Nabatean superiority was their unrivaled ability to procure water in the desert. Hieronymus describes this in detail. In modern terms, the Nabateans […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

We know Hieronymus’s work only from quotations in the history of Diodorus of Sicily. Diodorus, a first-century B.C. author, wrote a history of the world in 40 books.

This site is known in the Bible as Dedan. See Genesis 10:7, 25:3; 1 Chronicles 1:9; Isaiah 21:13; Jeremiah 25:23, 49:8; Ezekiel 25:13, 27:20, 38:13.

“Nympheaum” literally means “a temple of the nymph,” but in Roman architecture it is applied to any building containing a fountain.

These chronologies apply primarily to the history of the Nabateans in the Negev and do not necessarily apply indiscriminately to the whole of the Nabatean realm.

Oboda was excavated in 1958 by my teacher and friend Professor Michael Avi-Yonah, and from the autumn of that year to July 1961 by the author, on behalf of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

Most Arabian personal names Safaitic-Thamudic and Nabatean—have basic forms, such as ‘abd (“servant of”). The Safaitic-Thamudic names use this basic form as is; but the Nabateans add the letter “u,” so that it reads ‘abdu, thus distinguishing it from Safaitic-Thamudic. In addition, each personal name has additional forms, consisting of diminutives, feminine forms, etc. Safaitic-Thamudic names are represented in all forms, but the poorer Nabatean-Aramaic vocabulary has chosen at random this or that form. Moreover, numerous groups of personal names are not represented in Nabatean-Aramaic at all. From all this, I conclude that the Safaitic-Thamudic group is closer to the Arabian mother culture, from which the Nabateans, who were affiliated with this mother culture, picked out personal names at random; quite certainly not the other way around.

Herodotus, Diodorus of Sicily, Strabo, the Books of the Maccabees, Josephus Flavius, Stephanus of Byzantium and others. Except for names of their rulers, by which the Nabateans dated their inscriptions, the Nabateans made no allusion to historical events of any kind in their inscriptions.