029

Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven image, nor any manner of likeness, of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath. … Thou shalt not bow down unto them, nor serve them …” (Exodus 20:4, 5).

The Second Commandment’s prohibition against the worship of idols often became for Jews a prohibition against the making of figurative art. As The Hebrew Bible in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripisa makes abundantly clear, however, this interpretation of the proscription was not always followed. This handsomely produced book attempts to reveal the wealth not only of a few individual images, but also of extensively illustrated narrative cycles found in numerous manuscripts made for Jews during the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance. It achieves this admirable goal by unfolding, in the epic manner of the Bible itself, the major stories of the Hebrew Bible (what Christians refer to as the Old Testament) in chronological sequence. The author has written chapters on Adam and Eve, Noah, Abraham and Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses and Aaron, David, and Solomon. Two final chapters pick up stragglers: “The Man of God” discusses Samson, Job, Jonah, and Daniel; and “The Woman of Worth” deals with Miriam, Ruth, Esther, and Judith.

Since this is a book about the history 030of art, Sed-Rajna proceeds to discuss the iconographic traditions that governed the depiction of the events in these important biblical careers. It was not unusual, we learn, for Hebrew manuscripts to contain narrative cycles offering extensive “blow-by-blow” descriptions of the lives of these heroes and heroines of the Bible. Thirty-one different manuscripts are generously illustrated in the 180 -clearly printed reproductions, 60 of which are in excellent color. Sed-Rajna always includes proper biblical citations and references to the Midrash (exegetical homilies that she demonstrates also had a direct influence on the art). Although the book’s title refers only to Bibles, the author also discusses and reproduces numerous Haggadot (prayer books, read at the Passover service, that relate the story of Exodus), which were often illustrated.

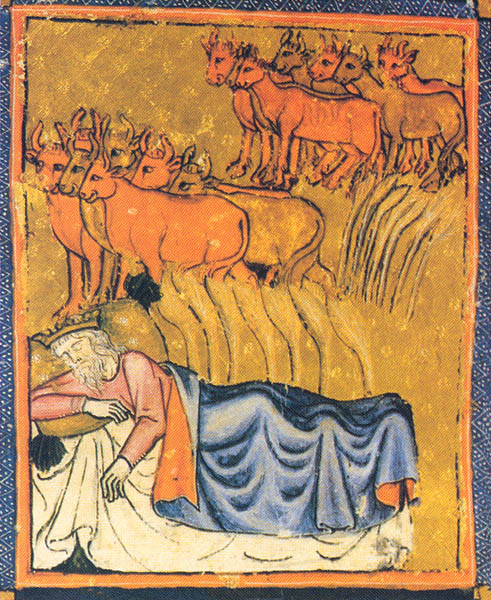

The abundance of pictures, accompanied by the elucidating commentary, is the great strength of this volume. For example, of the 34 full-page miniatures that form the important cycle in the Sarajevo Haggadah, painted about 1360 in Catalonia, a generous 19 (in whole or in part) have been reproduced. Nineteen, too, of the 41 full-page miniatures from the London Miscellany, painted in 13th-century France and one of the most beautiful of all Hebrew manuscripts, also appear here. The great Golden Haggadah, illuminated in Spain in the early 14th century, has 14 full-page quadripartite miniatures; the whole or a part of each has been included. Of the 34 full-page miniatures of the Catalan Haggadah, created about 1330, 17 (complete or in details) have been reproduced. This is a lot of pictures, and the end result is that the reader begins to comprehend the little-known richness of these manuscripts.

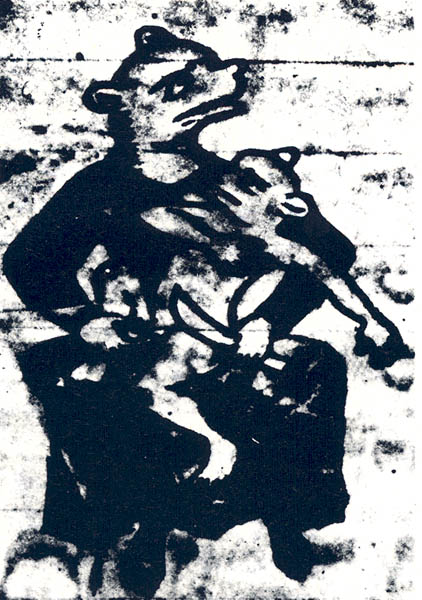

Some of these manuscripts reflect the reluctance to include the human figure in Jewish art, put this reluctance takes an unusual form. Fulfilling the letter of the putative proscription, if not quite the spirit, “human” figures were included, but were provided with the 032heads of birds or other animals. Thus in the German, 13th-century Laud Mahzor, a very canine-looking Abraham circumcises a puppy of an Isaac. Other manuscripts employ a variety of means to avoid showing the human face: heads are averted from the viewer to show only the back of the hair; hats are rakishly pulled down over the faces; and eyes are omitted or erased (see collage of three scenes from German-Jewish prayerbook). The animal heads do not influence the very human actions of these figures; consequently, such peculiarities do not enter into the author’s discussion, but these fascinating anatomies will surely interest the reader.

It would be unfair not to mention Sed-Rajna’s stated purpose in writing her book: The revelation of the discovery, for the first time, of the ancient sources of medieval Jewish iconography. The author theorizes that the evidence offered by the manuscripts points to the existence of Jewish archetypical cycles existing as early as 200 C.E.b She is not the first, however, to propose that medieval Jewish iconography depends on a much older—and lost—tradition, a tradition that also influenced Christian iconography as reflected in such important early manuscripts as the fifth-century Cotton Genesis or the sixth-century Vienna Genesis. Sed-Rajna promotes her thesis with reference to comparative illustrations that she cites in the notes, but she never includes them among the reproductions. Only with great perspicacity and a well-stocked library can the reader follow her arguments, and, even then, only the specialist will be interested. Sed-Rajna’s stated purpose underplays her book’s real achievement, as already mentioned: generous pictures clearly explained and made accessible to an interested public.

Students who are new to the field of Hebrew illuminated manuscripts and who might need a basic survey will have to turn to other handbooks for a general outline of their history. This is not a criticism of Sed-Rajna’s book; I mention it because even a minimal background on the chronology and geography of Jewish illuminated manuscripts will enhance the reader’s enjoyment of her publication. The most accessible surveys (in terms of cost, clarity and one’s ability to procure them) are Joseph Gutmann’s Hebrew Manuscript Painting (New York: George Braziller, 1978) and Bezalel Narkiss and Cecil Roth’s Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1978 [1969]). These two books complement Sed-Rajna’s publication, and all three together form the most up-to-date and concise source for the fascinating history of Hebrew illuminated manuscripts.

Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven image, nor any manner of likeness, of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath. … Thou shalt not bow down unto them, nor serve them …” (Exodus 20:4, 5). The Second Commandment’s prohibition against the worship of idols often became for Jews a prohibition against the making of figurative art. As The Hebrew Bible in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripisa makes abundantly clear, however, this interpretation of the proscription was not always followed. This handsomely produced book attempts to reveal the wealth not only of a […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username