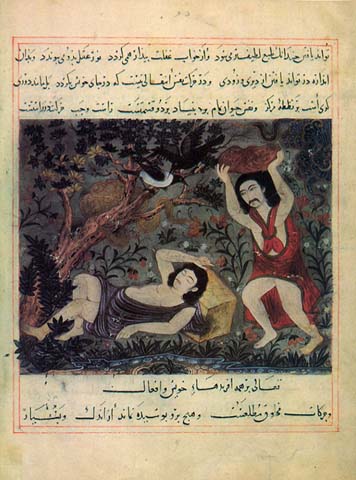

The first murder recounted in the Bible is Cain’s slaying of Abel (Genesis 4). Cain, the farmer, brought an unidentified agricultural offering to the Lord. Abel, the shepherd, on the other hand, brought the first born of his flock. The Lord ignored Cain’s offering but highly regarded Abel’s.

Cain’s reaction, according to most English translations, was anger. The New English Bible tells us, “Cain was very angry and his face fell.” In the cadenced measures of the traditional King James version we find “And Cain was very wroth, and his countenance fell.”

I believe that this is a mistranslation. The emotion which the Bible records here is depression not anger. The story of Cain and Abel is the first depressive episode mentioned in the Bible. This first case of depression led to the first Biblical murder.

The phrase, “his face fell,” clearly indicates depression rather than anger. In the literature of ancient Western Asia, the phrase “his face fell” was widely used to indicate depression or sadness, rather than anger. For example, in the Akkadian myth, “the Descent of Ishtar” in which Ishtar, the goddess of love, descends to the netherworld, the god Papsukal mourns Ishtar’s descent to “the land of no return” as follows:

“As for Papsukal, the vizier of the great gods, His countenance was fallen; his face [was gloomy]. Wearing a mourning garment, and with unkempt hair Papsukal went before Sin his father, weeping.”

Clearly Papsukal’s response to Ishtar’s departure cannot be described as anger.

In the Gilgamesh epic (best known because it contains a Flood story in some ways similar to the Biblical story of Noah), a woman named Siduri, a tavern-keeper, addresses the despondent hero Gilgamesh:

“[Your cheek]s are [emaciated]. Your face has fallen.”

There is no question here but that Gilgamesh is despondent and depressed, but not angry.

But let us turn directly to the Hebrew words which are so often translated as indicative of Cain’s anger. The Hebrew expression which is customarily translated “he was angry” is h

We find this usage of the Hebrew verb “to burn” in the book of Jonah. A vine from the gourd provided shelter for Jonah. A worm ate the gourd so that the prophet became exposed to the elements. A merciless sun beat down on him, and a scorching hot wind blew from the east. Jonah became faint and prayed for death: “I should be better dead than alive” (Jonah 4:8). God asked Jonah, “Are you so deeply grieved about the gourd plant?” The phrase I have translated “grieved” is h

The answer to the question as to why Biblical Hebrew should employ an expression denoting “burning” in referring to depression is that the Hebrew Bible has anticipated the observation made by Karl Abraham and Sigmund Freud that depression is really anger turned inward upon the self.2 The insight that depression is anger turned inward upon the self seems also to be reflected in Akkadianb usage. Akkadian expressions which mean literally “the chest became inflamed” are often used as idiomatic expressions for anger. This Akkadian usage is similar to the Biblical “when his heart becomes inflamed” (Deuteronomy 19:6). On many occasions, however, these Akkadian expressions are juxtaposed with such expressions as “I lamented,” denoting sadness, grief, or depression.

The larger context of the story also indicated that Cain’s reaction was depressive rather than angry. The Lord’s rejection of Cain’s offering meant to Cain, in Freudian terms, the loss of his love-object. Cain’s being rejected by his love-object results in a loss of self-esteem which is a primary characteristic of depression.3

When God sees Cain’s reaction, He tries to rouse him from his depression. In one of those typical, Biblical rhetorical questions, the Lord asks “Why are you depressed and why has your face fallen?” The question seems to imply, “You, Cain, have no need to be depressed.”

The Lord then utters a difficult Hebrew sentence which E. A. Speiser in his Anchor Genesis sensitively translates, “Surely if you act right, it should mean exaltation.” As Speiser points out, the Hebrew word for exaltation derives from a root meaning “to lift up.” The Biblical author clearly intends to draw a contrast between Cain’s “fallen” face and the potential for its being “lifted up.”

After God’s admonition to Cain the story continues, “Cain said to his brother Abel.” In the canonical Hebrew version of the Bible, known as the Masoretic text, there is a lapse at this point, a complete non sequitur. A new sentence abruptly begins, “When they were in the field, Cain set upon his brother Abel and killed him.”

Many ancient versions like the Greek Septuagint, the Samaritan recension in Hebrew, and several of the Jewish Targumsc provide a smooth transition by inserting the words, “Let us go into the field,” into the interrupted sentence. Modern commentators accept this emendation. Hence the verse in the New English Bible reads “Cain said to his brother Abel, ‘Let us go into the open country.’ While they were there, Cain attacked his brother Abel and murdered him.” In a new Jewish version,4 ellipsis dots are employed in this verse signifying that something has been omitted. The passage appears as follows “Cain said to his brother Abel … and when they were in the field, Cain set upon his brother Abel and killed him.”

Perhaps, however, the apparent ellipsis, the abrupt non-sequitur which precedes the announcement of the murder, was intentional. Perhaps the Biblical author is saying that this tragic act of violence was something out of the blue, something totally irrational.

In fact, modern psychoanalytic studies have suggested that depressed patients often regain their self-esteem by means of aggressive impulses released and directed against an object outside themselves.5 Indeed, this aggression “tends to be directed against close family members.”6

This, in fact, is what we find in the case of Cain, who loses his self-esteem as a result of his rejection by God. He becomes depressed; he cannot hold his head up; he cannot be talked out of his depression, which, according to psychoanalytic theory, is anger at his lost love-object turned inward upon himself. Then Cain regains his self-esteem by releasing aggressive impulses against his only sibling, Abel.

Thus the story of Cain and Abel may be a classic illustration of the consequences of a disease that has, in our own time, assumed epidemic proportions.

(For further details, see Mayer I. Gruber, “The Tragedy of Cain and Abel: A Case of Depression,” The Jewish Quarterly Review, N.S., Vol. 69, No. 2, pp. 89–97.)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Because God is asking a question of Jonah, the form le

Akkadian is a Semitic language that was written from left to right in syllabic cuneiform. Generally written with a reed stylus on clay tablets, Akkadian was also inscribed on stone monuments and on writing boards made of wood overlayed with a thin layer of wax. Native to Mesopotamia, Akkadian became an international language of diplomacy, trade, and culture. Hence documents in this language have been recovered from archaeological sites throughout the Middle East including Egypt, Syria, Israel, Turkey, and Iran as well as Iraq. The oldest documents found in Akkadian were written during the third millennium B.C.; the most modern documents belong to the New Testament period.

Targum literally means “translation.” The term generally designates a Jewish or Samaritan translation of the Scriptures into Aramaic. Aramaic, a language closely related to Hebrew, was a major international language in the Middle East from the middle of the eighth century B.C. until the seventh century A.D. Translations of the Hebrew Scriptures into Aramaic were composed from Second Temple times into the Middle Ages. In some Jewish communities the Targums are employed liturgically to this day.

Endnotes

D. Stanley Jones, “The Biological Origin of Love and Hate,” in Feelings and Emotions: the Loyola Symposium, ed. Magda B. Arnold (New York and London, 1970), pp. 27–28.

Karl Abraham, “Notes on the Psycho-Analytical Investigation and Treatment of Manic-Depressive and Allied Conditions,” in The Meaning of Despair, ed. Willard Gaylin, (New York, 1968), pp. 26–49; Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” in The Meaning of Despair, ed. Willard Gaylin, pp. 50–69.

Edward Bibring, “The Mechanism of Depression,” in The Meaning of Despair, ed. Willard Gaylin, p. 179–180.