Did Yahweh,a the Israelite God, have a consort? Like many other scholars, I believe that a substantial number of Israelites thought so. Unlike most others scholars, however, I believe that many of these same Israelites considered the sun a symbol or icon of Israel’s God, Yahweh. Yet early Israel was far more developed than we might guess from this; the same evidence that points to Yahweh as having a consort (or wife) and being symbolized by the sun, also points to an understanding of Yahweh as an abstract, non-anthropomorphic deity. In short, many early Israelites combined various notions about Yahweh that we would call “orthodox” and “pagan.” Unravelling these various strands proves to be a fascinating exercise.

Our principal evidence, in addition to the Bible, will be two archaeological finds familiar to long-time BAR readers—the pithoi (storage jars) from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud in the Sinai with their pictures and inscriptions;b and the famous four-tiered cult stand from Taanach that graced the cover of the

The Kuntillet ‘Ajrud pithoi were especially shocking when discovered because they seemed to suggest quite explicitly that Yahweh did have a consort. The site of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud was apparently a caravanserai where travelers could bed down for the night and, at the same time, pray for a safe journey. Based on the pottery and on the shape and stance of the letters in the inscriptions, the pithoi date to the eighth century B.C.E. In addition to their badly faded inscriptions, these pithoi also contain faint drawings of some scenes and figures, to which we will later return. For now, however, we will look at the inscriptions. Each pithos has an inscription that refers to Yahweh and to his Asherah (or, as I prefer, asherah).1 Pithos A, in the most commonly accepted interpretation, speaks of “Yahweh of Shomron (Samaria) and his asherah (or Asherah).” The inscription on Pithos B states, “I bless you by Yahweh of Temanc and by his asherah (or Asherah).”

For some scholars, whether these inscriptions refer to a consort of Yahweh depends on whether Asherah is spelled with a capital A or a small a. One scholar who favors the small-a (i.e. cult symbol) option for the inscriptions goes so far as to suggest that even references in the Bible to a goddess called (the) Asherah are mistaken or commonly misinterpreted and that there too we should see only a tree-like cult symbol called “the asherah.” In this view, there was no consort of Yahweh, just a cult symbol that only incidentally bore the name of the long-forgotten goddess Asherah.2 Examination of the Taanach cult stand will show, however, that the asherah as a cult symbol occurs right alongside a portrait of the goddess herself and that the goddess had thus not been separated from the cult symbol that bore her name. Thus, it makes little difference whether the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud inscriptions refer to the goddess herself or to her symbol. In other words, assuming continuity between the asherah at Taanach and Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, the inscriptions from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud imply Yahweh’s association with a consort even if the inscriptions refer only to her cult symbol named “asherah” with a lowercase a.

Some readers may have noticed by now my aversion to referring to the goddess symbolized by “the asherah” with the proper name Asherah. This is because a recent reevaluation persuasively argues that Asherah, like Baal, although often treated and translated as a proper name, is probably a common noun or title.3 That is why Asherah (and Baal) are often preceded by the definite article, “the” (h in Hebrew). Baal is thus more properly rendered “the lord” (or the like) and “Asherah” is better read as referring to a kind of goddess or class of goddess specified simply as “the asherah.”

If this is correct, the name of Yahweh’s consort may not have been preserved in the Bible (or in the inscriptions from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud). Therefore, I prefer not to use the name Asherah with a capital A (although it then becomes difficult to know exactly what to call Yahweh’s consort). The situation is further complicated by the fact that “the asherah” sometimes refers to a cult object rather than to a member of “the asherah” goddess class, as already noted.

Another inscription similar to those from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud and from the same period was found in a tomb at Khirbet el-Kom, eight miles west of Hebron. In this inscription, carved into a wall of the tomb, someone is blessed “by Yahweh” and “by his asherah.” Rather than the numerous drawings on the pithoi from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, only one image—of a hand—accompanies the Khirbet el-Kom inscription.

One of the most splintered scholarly arguments concerns the identification of the people in the drawings on the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud pithoi. Is there a drawing of Yahweh? Is there a drawing of his asherah? What about a symbol of these or other deities?

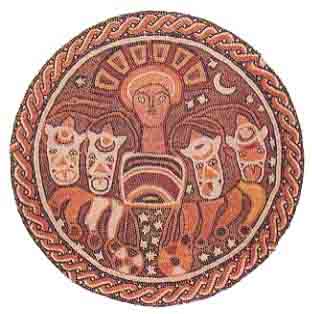

We will return later to these pictures. But first I want to take a careful look at the second artifact I referred to at the outset of this article—the four-tiered cult stand from Taanach, excavated in 1968 by the American archaeologist Paul Lapp. This magnificent cult stand, the exact function of which is unknown, has no inscriptions, only sculptured people, animals and other symbols. Our study of these religiously meaningful representations will prepare us for and lead us back to the drawings on the pithoi from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud. On the journey, we will learn not only that Yahweh did have a consort, but that at a very early period—the Taanach cult stand dates to the tenth century B.C.E.—Israel conceived of Yahweh abstractly and non-anthropomorphically. At this same time, Yahweh was also symbolically represented—at least occasionally—by the sun. All these strands of theological understanding of Yahweh and Yahweh worship existed simultaneously—a most elevated and abstract understanding within a pagan (though Yahwistic) context.

The Taanach cult stand is hollow and stands about 1.75 feet high. It is made of clay. At the top of the stand is a shallow basin with button-like decorations on the rim. The square shape of the stand gives an architectural impression (as opposed to most cult stands’ circular shape, which results from clay turned on a potter’s wheel). On the highest of its four tiers are two freestanding pillars typical of entrances to temples in Syria-Palestine. The stand seems to represent four temple scenes complete with the deities venerated in the temple. Although some of the scenes appear to be pagan in character, the four vignettes belong to the same (Yahwistic) complex, both physically and ideologically.

The four scenes on the four registers of the cult stand, from top to bottom, are as follows:

Tier 1: An animal, either a horse or a bull, above which is a sun-disk with wings (or the sun with rays). The scene is flanked, as previously noted, by freestanding pillars.

Tier 2: A pair of ibex reaching into a “tree of life.” This scene is flanked on either side by a lion.

Tier 3: A vacant space between two cherubim.

Tier 4: A nude female between two lions virtually identical to the lions on tier 2.

On the sides of tiers 2, 3 and 4 are the sides of the animals that flank the central part of the tier. On the sides of tier 1 are griffins (as lions are on tiers 2 and 4). The back of the stand is smooth, except for two square holes typical of fenestration on cult stands.

In a recent BAR article, Ruth Hestrin interpreted the imagery of this cult stand as representing the deities Asherah and Baal.d Hestrin’s interpretation of the stand is in many ways penetrating and insightful. But I believe she reached the wrong conclusion. The stand, I believe, represents Asherah and Yahweh, the Israelite God.

As Hestrin has noted, identical pairs of lions are poised on either side of the central deity on both tier 2 and tier 4. This suggests that the artisan sought to convey the same deity on these two tiers, albeit in two different ways. Hestrin correctly identifies this as the great mother goddess, commonly called Asherah, who can be represented either by a sacred tree (as on tier 2) or by a nude female (as on tier 4).4

If tiers 2 and 4 represent the same deity, it would be reasonable to expect this also to be the case with tiers 1 and 3. However, the central part of tier 3 is vacant. Naturally, Hestrin looked to tier 1 for the identity of this deity. She concluded that it was Baal and that therefore the stand as a whole involved Baal and his consort Asherah.

The linchpin of her identification of the deity represented in tier 1 is the animal in the center of the tier, which she interpreted as a bull, the symbol of Baal Hadad, the Canaanite storm god.5 Even if it is a bull, I believe it represents Yahweh—bull imagery was applied no less to Yahweh than to Baal. We need only recall the bull found at the Israelite shrine known simply as the Bull Site,e as well as some Biblical references (Exodus 32:1–8; 1 Kings 12:25–33; Hosea 8:6). So even if this animal is a bull, it could symbolize Yahweh as easily as Baal.

But I believe the identification of this animal as a bull is incorrect. More likely, it is a horse. With some apparent hesitation, Hestrin notes the absence of horns on this “bull.” That is because it is a young bull, she says. She rejects the identification of the animal as a horse on the ground that it has no mane. But horse figurines of the Iron Age are rarely depicted with flowing manes; they are either cropped, the equine equivalent of our “brush cut,” or omitted. (By the same token, Hestrin must identify the lions that, like the horse, similarly lack a mane, as lionesses.)

I have consulted two zoological experts who conclude that the animal is far more likely to be an equine than a bovine creature. Peter W. Physick-Sheard of the Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada, discerned a horse rather than a calf on the basis of the following criteria: (1) The animal has a full tail stemming from the croup (as opposed to a rope tail with a bushy end dangling between the legs). (2) The ears are positioned high on the head and are erect (as opposed to droopy ears positioned laterally). (3) The animal has a long muzzle and sharp angle to the jaw as well as a flat upper part of the head from forehead to muzzle. (4) The hooves (still intact on the left side) are large; the effort to include them on an otherwise crudely crafted animal suggests, in Physick-Sheard’s words, “Even in the days of King Solomon the importance of the hoof to a working horse was evident!” (5) The prancing posture conveys a horse’s strength, agility and athletic prowess (as opposed to a calf’s posture of playfulness, which seems less consistent with the serious nature of the stand).6

Why is the identification of this animal important? For one thing, if it is a horse, then it cannot be identified with Baal. And for another, the imagery of a horse prominently portrayed below the blazing sun readily brings to mind a similar cultic scene portrayed in the Bible. In the seventh century B.C.E., King Josiah of Judah abolished an ancient Yahwistic tradition, as follows:

“He [Josiah] removed the horses that the kings of Judah had dedicated to the sun, at the entrance of the house of the Lord … ; and he burned the chariots of the sun with fire” (2 Kings 23:11).

This passage refers to a cultic procession of horses and chariot(s) of the sun in association with the Jerusalem Temple, attributed not to the heretical king Manasseh who ruled only a few years before, but to “the kings of Judah” (plural), which suggests a rite with a considerable history. Tier 1 of the Taanach cult stand shares no fewer than five things in common with this Biblical passage: (1) an Israelite context; (2) a horse; (3) the sun; (4) an allusion to chariotry;7 and (5) a location at the Temple—specifically at the “entrance” to the Temple—that is, near the freestanding pillars.8

In this connection, we may recall a terra-cotta figurine from Hazor, found in what was probably a royal barrack. Although this figurine also has been confused with a bull, the same two experts are convinced it depicts a horse and not a bull, as is commonly thought. (Physick-Sheard is so certain this is a horse that he thought it was my way of testing his judgment about the Taanach horse!) Like the horse on the top tier of the Taanach cult stand, the horse figurine from Hazor is early (late tenth century B.C.E.) and probably comes from a royal context (the barracks of a member of the Israelite king’s army).9

Finally, let us look at tier 3—the odd tier out. Each of the other tiers has a deity or the symbol of a deity in the center. Tier 3 is vacant in the center, however. The conspicuous absence of a deity here was noted by Hestrin, who suggested that “the figurine of a deity may have been placed inside the hollow stand and seen through this opening.”10 However, no image was found inside the stand, or in the silt deposit where it was found, that would support Hestrin’s suggestion.

I believe that the absence of a deity form here is intentional. (I assume Hestrin refers to me when she states, “One scholar, however, says the empty space represents the new Israelite concept of the incorporeal God Yahweh.”11) “Pictured” in this vacancy between the cherubim is the invisible, abstract deity called Yahweh, represented in tier 1 by his symbol, the sun.

The stand has an overall structure. Tiers 2 and 4 represent “Asherah”—her symbol, the tree of life, flanked by ibex on tier 2 (Hestrin herself has demonstrated that this is her symbol), and the goddess herself, nude, on tier 4. These two tiers are united visually by the lions flanking the center figure on both tiers. With the two sets of lions, we should expect the same deity, once her representation and the second time her symbol. In tiers 1 and 3, we should expect the same parallels we find in tiers 2 and 4. In tier 1, we have a horse with the symbol of the sun in the center, which the Bible itself reports as having been in the Temple of Yahweh. This is flanked by a freestanding pillar on either side, which the Bible tells us characterized the Temple of Yahweh. Then we have a vacant space in tier 3. From every appearance, this tier was designed this way; nothing has broken off. It would seem that this deity is characterized by the impossibility of a representation or a depiction—an abstract, non-anthropomorphic deity. In short, the pattern emerges of Asherah in symbol and “in person” on tiers 2 and 4 respectively, matched by Yahweh in symbol and “in person” on tiers 1 and 3 respectively.

Several other considerations support my idea that the asherah goddess and Yahweh are represented on the Taanach stand. The vacant space in the center of tier 3 is flanked by cherubim. In the Holy of Holies in Yahweh’s Jerusalem Temple, where He dwelled, two cherubim kept guard, and the presence of Yahweh was marked only by vacant space. The deity represented is Yahweh, not Baal. He is abstract and non-anthropomorphic, and, as we have seen, his symbol, although it may have offended purists, was so widely represented as the sun that that symbol found its way into the Temple itself in association with a horse, which is also found on tier 1.

“Yahweh of Hosts who dwells (among) the cherubim” (1 Samuel 4:4; 2 Samuel 6:2; 1 Kings 8:6–7) is an expression for the God of Israel that is virtually synonymous with the theology of the Jerusalem Temple. Here, near the center of this cult stand, is an archaeological vignette of a well-attested Israelite deity—Yahweh—in association with cherubim. I would further suggest that the enigmatic expression “Yahweh of Hosts” (Yahweh Tsva’ot) implies that Yahweh was head of the stars and was to be identified with the most important star of all, the sun. Support for this suggestion is found in several Biblical passages: “You who are enthroned on the cherubim, shine forth. … Restore us, O God; let your face shine” (Psalm 80:2–3); “The Lord came from Sinai, and dawned from Seir upon us; he shone forth from Mount Paran” (Deuteronomy 33:2). Moreover, in Jewish incantations and prayers of the Graeco-Roman period we find such prayers as “Hail Helios, thou God in the heavens, your name is mighty … ” and an incantation that invokes “Helios on the cherubim.”12 (See also Judges 5:19–20.)

Thus, tier 1 of the Taanach cult stand bears testimony to an aspect of Israelite religion that Biblical writers did not ever explicitly condone, but that, to their credit, they nonetheless did acknowledge in places like 2 Kings 23:11 and Ezekiel 8:16. (Ezekiel 8:16 tells of a vision in which men turn their back on Yahweh’s Temple and prostrate themselves to the sun.)

Another factor suggesting that the deity represented on tiers 1 and 3 was Yahweh, is that Taanach at this time was squarely within Israelite territory, and had been Israelite for a long time.13 This is just where we would expect Yahweh to be worshiped, even if evidenced by his symbol, the sun. As William Dever has remarked, this cult stand and another like it found at the same site in 1902 “abound in evidence for Israelite syncretistic iconography.”14

I conclude, then, that the Taanach cult stand portrays not Baal and Asherah, but rather Yahweh and the mother goddess symbolized by the asherah. This view is consistent with a recent scholarly monograph claiming that the “goddess Asherah was never associated intimately with Baal in Canaanite religion,” but rather with Yahweh within the context of Israelite religion.15

This conclusion demonstrates that the “orthodox” notion of the invisible God present within His temple amid the cherubim was already in place at least as early as the tenth century B.C.E., but it also shows that the “unorthodox” notion that the sun was a cultic symbol (or icon) of “Yahweh of Hosts who dwells among the cherubim” (see, for example, 1 Samuel 4:4; 2 Samuel 6:2; 2 Kings 19:15; Isaiah 37:16) was also widespread. Moreover, it shows that Yahweh and his consort were linked already in the tenth century B.C.E. and in places less obscure than Kuntillet ‘Ajrud and Khirbet el-Kom.

This analysis can now help us answer some of the most perplexing questions about the drawings on the pithoi from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, questions relating to the identification of the figures on these storage jars. Pithos A from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, famous for its reference to “Yahweh of Samaria and his asherah,” pictures a sacred tree flanked by ibex, a striking parallel to what we see on tier 2 of the Tanaach cult stand. In support of the validity of the parallel, the ibex both at Taanach and at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud adopt identical postures in relation to the sacred tree of life and in both cases they appear in direct association with lions. Just as this tree of life represents the asherah goddess on the Taanach stand, so on the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud pithos. And just as we find this same goddess in association with Yahweh at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, so at Tanaach.

Finding a picture of Yahweh on the pithoi from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud is more difficult. Soon after the publication of the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud pithoi, Asherah was identified with a female lyre player pictured on Pithos A with two male figures. Yahweh, it was suggested, was a male figure to the far left of the female lyre player. But, it is now generally agreed that this figure is the Egyptian god Bes, with his customary feather headdress and arms akimbo, as well as the tail (or penis) hanging between his legs. The middle figure in this trio is probably also Bes, although the figure appears to have circles representing female breasts (as does the lyre player). As for the lyre player, she is just that.

If not the god Bes on Pithos A, where (if anywhere) might we find Yahweh?

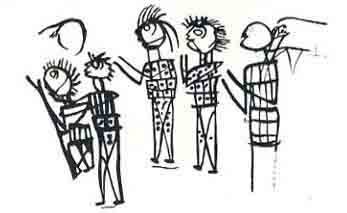

I believe Yahweh can be found on a drawing on Pithos B, which also contains an inscriptional reference to Yahweh and his asherah. Pictured on this pithos is a line of five worshipers with hands raised in a gesture of adoration before a deity. The deity they are worshiping, however, is not drawn. What deity, then, are the processioners adoring? A clue is provided by the direction in which the processioners are looking, a feature overlooked in an otherwise painstaking study of all aspects of the drawings.16 The general orientation of the processioners is undeniably skyward; this suggests that the object of the processioners’ devotion was situated in the sky. But for the crude nature of the drawings, one might speculate that the artisan, by drawing five heads each oriented progressively more skyward than the one before, intended to create the effect of their looking at an object “in motion.” Their gaze seems to move from a point low in the sky to a position directly overhead (or vice versa). Were they tracking the sun? (The effect is roughly akin to a sequence of still frames in a movie clip.) Whether or not this sequence was intended, it does seem clear that they are looking skyward, quite probably toward the sun. We have already shown that several Biblical passages tell of Israelites venerating the sun, if only as a cult symbol or icon of Yahweh (see Jeremiah 8:2; Ezekiel 8:16–17; 2 Kings 23:5, 11; cf. Deuteronomy 4:19, 17:3).

The first-century C.E. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus tells us that, much later, the Essenes would offer to their God—unquestionably Yahweh—certain prayers before dawn “as though entreating him to rise.”17 We also find depictions of Helios, the Greek sun-god, on the mosaic pavements of numerous ancient synagogues, such as Beth Alpha in the Jezreel Valley and Hammath Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee. Further, Solomon’s Temple was oriented to the east (as, later, were Christian churches—Christ too was sometimes pictured as a sun-god).

The processioners on the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud pithos not only look skyward, they also gesture with their arms near their mouth. The figure on the left seems to hold his hands in front of his mouth. The gesture with the hand recalls the giant hand on the Khirbet el-Kom inscription. And both the sun-gazing and the gesture recall a passage from Job 31:26–28:

“If I looked at the shining light,

Or the moon marching in splendor,

And my mind was secretly seduced,

And my hand kissed my mouth;

That were perfidious sin,

I had betrayed God on high.”18

Apparently not every Israelite agreed with Job, however, that it was inappropriate to worship the true God by looking at the sun while gesturing with the hand! The line of worshipers with heads lifted skyward toward an object that the ‘Ajrud artisan chose not to draw,19 are worshiping Yahweh as they look at the sun, an old icon of Yahweh of Hosts, later banned by Deuteronomistic reformers.

In sum, I suggest that the Taanach cult stand offers us the earliest pictorial portraits of Yahweh worship yet discovered by archaeologists. It confirms that “the asherah” denoted not just a cult symbol of Yahweh, but a consort. At the same time it points powerfully to the notion of the incorporeal deity, Yahweh who dwells amid the cherubim. And finally, it points to a mysterious third dimension admixture of “orthodox” and “pagan” notions associated with Yahweh and his asherah—sun worship, attested by the sun horse of Taanach, the processioners of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud and perhaps also by the giant hand on the Khirbet el-Kom inscription.

For further details and additional references, see J. Glen Taylor, “The Two Earliest Known Representations of Yahweh,” Ascribe to the Lord: Biblical and other studies in memory of Peter C. Craigie, ed. Lyle Eslinger and Taylor; (JSOTSup 67; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1988), pp. 557–566; and Taylor, Yahweh and the Sun: Biblical and Archaeological Evidence for Sun Worship in Ancient Israel (JSOTSup 111; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993).

MLA Citation

Footnotes

In Hebrew, the name of Israel’s god consists of the four letters YHWH and is known as the tetragrammaton. No one knows how YHWH was pronounced, but it is usually vocalized as Yahweh.

See Ze’ev Meshel, “Did Yahweh Have a Consort?” BAR 05:02; André Lemaire, “Who or What Was Yahweh’s Asherah?” BAR 10:06; and Ruth Hestrin, “Understanding Asherah—Exploring Semitic Iconography,” BAR 17:05.

Teman is a reference either to the region of Edom or the “south country” in general; compare Habakkuk 3:3.

Ruth Hestrin, “Understanding Asherah—Exploring Semitic Iconography,” BAR 17:05.

See Amihai Mazar, “Bronze Bull Found in Israelite ‘High Place’ from the Time of the Judges,” BAR 09:05; Hershel Shanks, “Two Early Israelite Cult Sites Now Questioned,” BAR 14:01.

Endnotes

An alternative to “his Asherah,” which curiously refers to a proper name with the possessive “his,” is “Asherata,” a variation on the Biblical name Asherah that is attested at Ekron during the Iron Age. For new evidence in favor of this option, see Richard Hess, “Yahweh and His Asherah? Epigraphic Evidence for Religious Pluralism in Old Testament Times,” One God, One Lord in a World of Religious Pluralism, ed. Bruce Winter and David Wright (Cambridge: Tyndale House, 1991) pp. 5–33. For Asherat(a) at Ekron, see Seymour Gitin, “Ekron of the Philistines: Part II,” BAR 16:02.

See, for example, Mark S. Smith, Early History of God (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990), pp. 88–94. Smith is thus inclined to believe that the reference to the goddess Asherah in 1 Kings 18:19 was originally a reference to the goddess Astarte and that other apparent references to the goddess could rather be to a mere cultic symbol, an idolatrous entity that received offerings.

Baruch Halpern, “The Baal (and the Asherah) in Seventh-Century Judah: YHWH’s Retainers Retired.” Baltzer FS, pp. 115–50.

Ruth Hestrin, “The Cult Stand from Taanach and its Religious Background,” Studia Phoenicia V (1987), pp. 67–71, 74; Hestrin, “Understanding Asherah: Exploring Semitic Iconography,” BAR 17:05.

Letter to the author from Professor Peter W. Physick-Sheard. Hestrin claims to rely on the assessment of Prof. Eitan Cernov of the Hebrew University for the identification of the animals (“Cult Stand from Taanach,” p. 56, n. 5). With the help of my friend Israel Ephal, I contacted Professor Cernov to see why his opinion differed from the judgment of the experts I consulted. Professor Cernov stated emphatically that he never had more than passing familiarity with the stand.

An indirect allusion to chariotry may be inferred from the presence not only of a horse in relation to the sun, but from the presence of a griffin as well. Both were commonly thought to draw the chariot of the sun god in the Graeco-Roman world. For notes and reference, see J.Glen Taylor, Yahweh and the Sun: Biblical and Archaeological Evidence for Sun Worship in Ancient Israel, (JSOTSup 111; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993), pp. 34–36.

Some readers will recall that at a site a few hundred yards from the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, Kathleen Kenyon excavated several horse figurines, a few of which seem to bear sun-disks between their ears. See “The Mystery of the Horses of the Sun at the Temple Entrance,” BAR 04:02. Although the horses might reflect a solar cult like the one described in 2 Kings 23:11, I believe that the so-called sun disks are bizarre examples of various odd-shaped “blobs” found on various animal figurines in the Iron II Period. For further explanation, see my Yahweh and the Sun, pp. 58–66.

See Yigael Yadin, Hazor: The Rediscovery of a Great Citadel of the Bible (New York: Random House, 1975), p. 186–189, for illustrations and discussion of the Hazor figurine.

See Hans-Peter Stahli, Solare Elemente im Jahweglauben des Alten Testaments (Freiburg/Göttingen: Universitätsverlag/Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1985), p. 4. On a solar understanding of “Yahweh of Hosts,” see further my Yahweh and the Sun, pp. 99–105.

On the Israelite nature of Taanach at this period, see, for example, Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible (Doubleday: New York, 1990), p. 333; and see Joshua 12:21, 21:25, 1 Kings 4:12.

William G. Dever, “Material Remains and the Cult in Ancient Israel: An Essay in Archaeological Systematics,” The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth, ed. Carol L. Meyers and Michael O’Connor (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1983), p. 573.

Saul M. Olyan, Asherah and the Cult of Yahweh in Israel, SBLMS 34 (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988), p. 73.

Pirhiya Beck, “The Drawings from Horvat Teiman (Kuntillet ‘Ajrud),” Tel Aviv 9 (1982), pp. 36–40.

The translation is by Marvin Pope, Job, Anchor Bible 15, 3rd ed. (Garden City: Doubleday, 1973), p. 227. Although traditionally understood to contrast the worship of two separate deities, the passage can also be taken to set in contrast appropriate and inappropriate ways of worshiping the same deity, namely God.