Were There Women at Qumran?

048

Since the discovery of the very first Dead Sea Scrolls (in Cave 1Q), their writers have been associated with the Essenes. One of the three “philosophical schools” of ancient Judaism (along with the Pharisees and the Sadducees), the Essenes have been described by Josephus Flavius, discussed by Philo of Alexandria, and mentioned briefly by Pliny the Elder. The similarities between what these ancient authors said about the Essenes and what was written in the Dead Sea Scrolls include a voluntary association within Judaism, rules for entry into and expulsion from that association, a strict hierarchy and rules within the association, a shared community of goods, and a tension with the wider Jewish society. These similarities were, and still are, good reasons to identify the Qumran scrolls community with the Essenes. However, a major difficulty with the Qumran-Essene identification is the question of women and their position in the Jewish movement as described in the sectarian scrolls.

Josephus, Philo, and Pliny all agree that the Essenes shunned marriage and that their sectarian enclaves did not include women and children. The Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo in particular was firm in this position (Hypothetica 8.6–7). The Jewish historian Josephus, to be sure, mentions another order of Essenes who married for the purpose of procreation and whose communities, therefore, included women and children:

There exists another order of Essenes who, although in agreement with the others on the way of life, usages, and customs, are separated from them on the subject of marriage. Indeed, they believe that people who do not marry cut off a very important part of life, namely, the propagation of the species; and all the more so that if everyone adopted the same opinion the race would very quickly disappear. Nevertheless, they observe their women for three years. When they [the women] have purified themselves three times and thus proved themselves capable of bearing children, they then marry them. And when they are pregnant they 049have no intercourse with them, thereby showing that they do not marry for pleasure but because it is necessary to have children. The women bathe wrapped in linen, whereas the men wear a loin-cloth. Such are the customs of this order.

—(Jewish War 2.160–161)

However, most scholars deemed this subset to be secondary to the main order of Essenes, since it is not mentioned by Philo. Thus, the texts from Cave 1Q and the classical sources both seem to portray the Essenes as a celibate male Jewish community—unusual if not unique in Second Temple Judaism.

Father Roland de Vaux, who in the 1950s excavated Khirbet Qumran near the 11 caves with scrolls, seemed assured of the identification of Qumran’s inhabitants with the Essenes, placing particular emphasis on this testimony of Pliny:

To the west the Essenes have put the necessary distance between themselves and the insalubrious shore. They are a people unique of its kind and admirable beyond all others in the whole world, without women and renouncing love entirely, without money, and having for company only the palm trees. Owing to the throng of newcomers, this people is daily reborn in equal number; indeed, those whom, wearied by the fluctuations of fortune, life leads to adopt their customs, stream in in great numbers. Thus, unbelievable though this may seem, for thousands of centuries a race has existed which is eternal yet into which no one is born: so fruitful for them is the repentance which others feel for their past lives!

—(Natural History 5.17, 4)

050

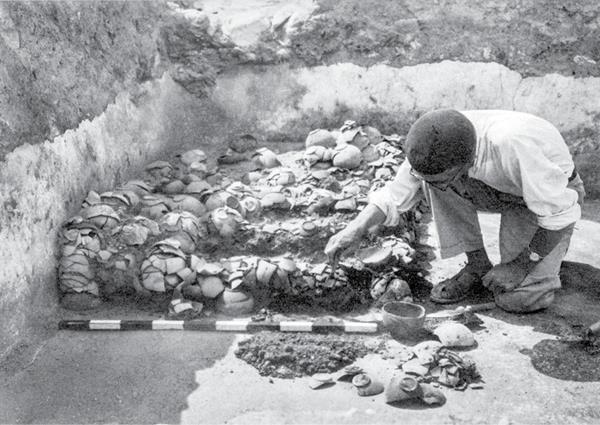

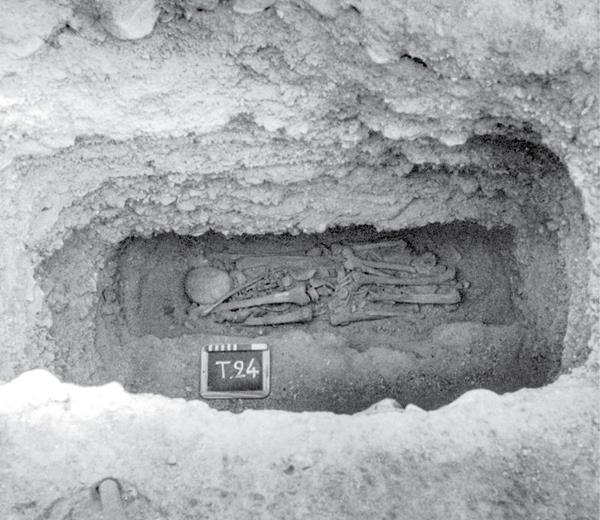

The character of the architecture at Qumran was also telling. It did not contain any family dwellings, but only communal buildings, indicating that the inhabitants did not live in normal family units. In addition, the graves excavated from the cemetery contained mostly male skeletons. These factors led de Vaux to conclude that the settlement at Qumran was a community of celibate Essene males living a communal lifestyle in a desert retreat, resembling later early Christian monasteries.

The correspondence between the archaeological and textual evidence led to what became known as the Qumran-Essene hypothesis: The scrolls from the 11 caves in the vicinity of Qumran were the possession of the Essene sect; Qumran was the main, if not the only, Essene settlement; and Qumran was an all-male community. Qumran became thought of as a place with no women and children.

This consensus began to break down in the late 1980s, as more and more of the fragmentary material from Cave 4Q was being published. The work of Eileen Schuller of McMaster University was especially important in this regard. Schuller demonstrated that women were, in fact, accepted constituents of the sectarian movement portrayed in the Qumran scrolls.1 Mainstream scholarship began to acknowledge that the majority of the Qumran sectarian scrolls assumed the presence of women and children in the 051sectarian community and legislated for that presence, albeit from a male point of view. Today, the textual evidence for the presence of women and children in the sectarian community described in the Qumran manuscripts is considered unassailable.

The archaeological record at Qumran and the testimony of the classical sources, however, point in a different direction. So can we somehow reconcile these two sets of data and draw a coherent picture of the lifestyle and purpose of the Qumran settlement? Let’s begin with the archaeological evidence.

Women and children are largely missing in the archaeological record at Qumran. While some female-gender objects, such as hairnets or female garments, would have been destroyed in the conflagration that consumed the buildings in 68 C.E., other female-gender items, such as spindle whorls, jewelry, and mirrors, would have survived.2 But no such objects were found in the Second Temple period remains. This strongly implies that women (and children) did not live at Qumran.

Qumran’s main cemetery provides some evidence for female burials. Out of approximately 1,200 graves from the Second Temple period, 93 have been excavated. Of those, nine skeletons appear to be female.3 No children have been identified. In a normal necropolis, one would expect a much higher percentage of women and children, owing to their high mortality rates in the ancient world. Yet the few female burials in the Qumran cemetery are enough to support the case that women were associated with the Qumran community.

In sum, the archaeological evidence indicates that the community at Qumran during the Second Temple period was almost entirely male during the roughly 150 years of its existence, although a few women were buried in the cemetery. Perhaps these women stayed at Qumran for only a short period of time and thus left no trace in the archaeological record. In any case, Qumran’s archaeological record would seem to agree with the portrait of celibate Essenes found in the classical sources.

When evaluating the classical authors, it is helpful to keep in mind the audience for which Josephus, Philo, and Pliny were writing—a non-Jewish, elite Roman audience in the first century C.E. They all, in one way or another, wished to present the Essenes as the Jewish epitome of Greek philosophical perfection. This perfection would include the ability to control their passions, especially their sexual passions. Therefore, if a certain percentage of the Essene sect did not marry or live in regular family units (for whatever reason), Josephus, Philo, and Pliny would emphasize that characteristic, in the cases of Philo and Pliny ignoring any other evidence. The fact that Josephus mentions another order 052of Essenes that did marry (for the purposes of procreation, as quoted above) probably indicates that marriage among the Essenes was the normal way of life.

This suggestion accords with the Damascus Document and other sectarian texts from Qumran that legislate for or otherwise mention the presence of women and children in the sectarian movement. However, at Qumran (which seems to be the place that Pliny is describing), the sectarian community was almost entirely male and, we may assume, sexually abstinent. Thus, while the bulk of the evidence of the Qumran sectarian manuscripts points to the “marrying Essenes,” the archaeological evidence and the classical sources support the “celibate Essenes.” It would seem, then, that Josephus was right: There were two types of Essenes. The “non-marrying” Essenes were found at Qumran, which explains its archaeological remains.

But why was Qumran an all-male community? I believe the answer lies in the purpose of the settlement. Many functions have been proposed for Qumran, including a fortress, luxury villa, pottery production center, and seasonal industrial complex tied to Jericho. Yet none of these proposals provides a satisfactory answer for all the evidence from not only the buildings but also the caves surrounding the complex, in 11 of which manuscript fragments have been discovered.

The ceramics found at the site and in the caves are identical in time period, forms, paste (consistency of clay), and lack of decoration.4 This is especially true for the “scroll jar,” a hole-mouthed cylindrical jar with the bowl-shaped lid, used for scroll storage in the caves and for varied uses, such as food storage, in the settlement. These cylindrical jars were manufactured at Qumran, since wasters (defective jars discarded during production) were found in the dumps around the buildings. These jars are almost unique to Qumran; they are found nowhere else in Judea except for one or two isolated examples from sites around the Dead Sea.

The ceramic evidence alone indicates that the 053caves with their scrolls and the buildings belong together. Further, the caves are connected to the buildings in other ways. The six manmade caves dug out of the marl terrace (4Q–5Q, 7Q–10Q) are all located on the same spur overlooking the Dead Sea on which the buildings sit. Paths and stairways connect those caves and the buildings, and three caves (7Q–9Q) can be reached only by walking through the settlement. The natural six caves in the cliffs above the settlement (1Q–3Q, 6Q, 11Q, 53) are also connected to the buildings by rough paths. Thus, the caves and their scrolls must be considered in any reconstruction of the site’s function.

The presence of approximately 800 fragmentary scrolls in the caves suggests a scribal community of some kind at Qumran. There is evidence for writing and scroll manufacture and repair in the settlement. Six to eight inkwells have been recovered, along with scroll tabs and ties, writing implements, and a bronze needle that may have been used for sewing scroll sheets together. In the main building of the settlement, rooms have been plausibly identified as library rooms and a scroll repair workshop.

And then there are the scrolls themselves, found in the 11 caves that are part of the archaeological landscape of Qumran. These scrolls form one collection, a library gathered by the inhabitants of Qumran over the course of the settlement’s existence. According to their paleographic characteristics, the scrolls all come from the same time period. The oldest were copied in the mid-third century B.C.E., while the latest date to the third quarter of the first century C.E., around the time when the Romans destroyed the settlement.

All of this indicates that one of the main activities of the Qumran settlement was the collection, copying, repair, and storage of scroll manuscripts that constituted the library of the Essene movement. Therefore, the largest percentage of Qumran’s population at any given time would have been scribes and their support staff—an all-male community, as we have no evidence for female scribes in Second Temple Judea. If these scribes observed a high degree of ritual purity while working on sacred texts, they may have eschewed sexual activity during their residence at Qumran. This would account for the almost complete absence of women in the archaeological record from the site and for Pliny’s report that the Essenes at Qumran lived “without women.”

Elsewhere in Judea, the Essenes would have lived in normal family units while practicing their particular rules as reflected in the Damascus Document and other texts. However, because of their strict rules of sexual conduct, there may have been a higher rate of non-marriage among the Essenes than other Jewish movements of the time. This could have led to Josephus’s and Philo’s claims that the Essenes forswore marriage.

Were the Essenes a group that embraced celibacy as a way of life? Their own documents tell us that the answer is no. However, they did observe strict rules for sexual purity for both men and women, which may have led to lower rates of marriage than was common among ancient Jews. This tendency and the function of Qumran as an Essene scribal center jointly account for the almost entire absence of women at Qumran. I believe that this scenario can reconcile the evidence of the sectarian scrolls, the archaeological record at Qumran, and the testimony of Josephus, Philo, and Pliny.

Qumran is widely believed to have been an Essene settlement. But how does this identification square with the role of women in the Jewish sect as described in the Dead Sea Scrolls, which likely originated in this supposedly celibate community?

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

1.

See Eileen M. Schuller, “Women in the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in Michael O. Wise, Norman Golb, John J. Collins, and Dennis Pardee, eds., Methods of Investigation of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Khirbet Qumran Site, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 722 (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1994), pp. 115-132.

2.

See Jodi Magness, Debating Qumran: Collected Essays on Its Archaeology (Leuven: Peeters, 2004), pp. 113-150.

3.

Some excavated graves in the South Cemetery, located across the wadi from the main cemetery, are most likely later burials by other groups, such as passing Bedouin.

4.

Jodi Magness, “The Connection Between the Site of Qumran and the Scroll Caves in Light of the Ceramic Evidence,” in Marcello Fidanzio, ed., The Caves of Qumran: Proceedings of the International Conference, Lugano 2014, Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah 118 (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp. 184-193.