The Babylonian flood stories are similar to the Genesis flood story in many ways, but they are also very different. If we look deeply enough into those Babylonian flood stories, they teach us how to understand the structure of the Genesis flood story. At the same time such a comparison also emphasizes how different the Genesis flood story is from anything that preceded it.

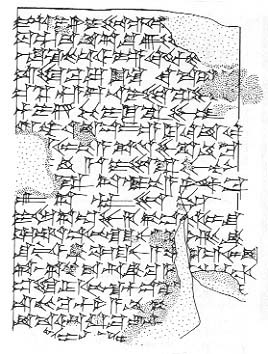

Three different Babylonian stories of the flood have survived: the Sumerian Flood Story, the eleventh tablet of the Gilgamesh Epic, and the Atrahasis Epic. Of these, the best known is Gilgamesh XI, which was one of the earliest cuneiform texts to be discovered and published. In 1872 George Smith read a paper called “The Chaldean Account of the Deluge” in which he presented fragments of the flood story from the Gilgamesh Epic. These fragments, dating from the seventh century B.C., were discovered in the library of King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh. However, other examples of tablets of this epic date from about 1000 years earlier than the fragments from Nineveh. These earlier tablets are evidence that the composition of the epic and the flood story contained in it occurred no later than the beginning of the second millennium B.C.; also, many of the episodes included in the epic have prototypes in the Sumerian language which are much older than the composition of the Gilgamesh Epic.

The other Babylonian telling of the flood, that of the Atrahasis Epic, is the most recently discovered. Although later versions of the flood episode from the Atrahasis Epic had been known for a long time, the structure of the epic, and therefore the context of the flood story, was not understood until Laessoe reconstructed the work in (1956).1 In 1965 many additional texts from the epic were published,2 including an Old Babylonian copy made around 1650 B.C., which is now our most complete surviving recension of the tale. These new texts greatly increased our knowledge of the epic and served as the foundation for the English edition of the Atrahasis Epic.3

As is true of other Babylonian compositions, the Atrahasis Epic utilizes many old mythical motifs and episodes, and many of the elements of the creation story found in the first tablet of the Epic can be traced back to earlier Sumerian compositions. We do not, however, know whether the story of the deluge ultimately dates back to Sumerian sources, or whether originally it might have been composed in Akkadian, the Semitic language of Babylonia. The single example of the telling of the flood in Sumerian that we have is the Sumerian Flood Story,4 found on only one extant tablet, most probably dating from the Late Old Babylonian Period (ca. 1650–1600 B.C.). We do not know if there were earlier Sumerian versions of this story.

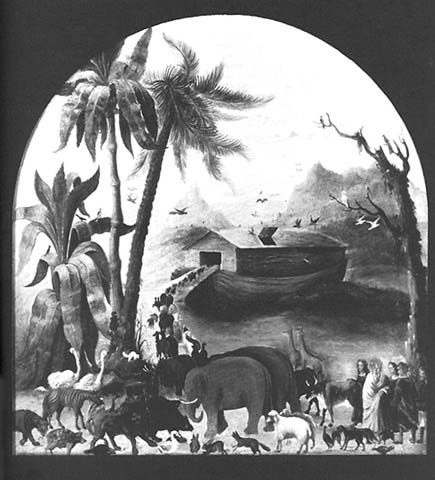

The Babylonian flood stories contain many details which also occur in the flood story in Genesis. Such details in the story as the building of an ark, the placing of animals in the ark, the landing of the ark on a mountain, and the sending forth of birds to see whether the waters had receded indicate quite clearly that the Genesis flood story is intimately related to the Babylonian flood stories and is indeed part of the same “flood” tradition. However, while there are great similarities between the Biblical and Babylonian flood stories, there are also very fundamental differences, and it is just as important that we focus on these fundamental differences as on the similarities.

It is not easy to compare the flood story in Genesis with that in the Gilgamesh Epic because they are told for different reasons and from different perspectives. In the Gilgamesh Epic the story of the flood is related as part of the tale of Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality. Utnapishtim tells his descendent, Gilgamesh, the story of the flood in order to tell Gilgamesh how he, Utnapishtim, became immortal; in so doing, he shows Gilgamesh that he cannot become immortal in the same way. Gilgamesh has sought out Utnapishtim in order to find out how to become immortal, and asks him “As I look upon you, Utnapishtim, your features are not strange; you are just as I … how did you join the Assembly of the gods in your quest for life?” (Gilgamesh XI:2–7); that is, how did you become immortal? Utnapishtim then proceeds to answer Gilgamesh by telling him how he became immortal, i.e. by telling him the story of the flood. He relates how the god Ea instructed him to build an ark and to take on it the seed of all living things. Utnapishtim did so, informing the elders of his city that Enlil was angry with him, that he could no longer reside in the city and that he was going down to the deep to live with Ea. When the flood arrived Utnapishtim boarded the ship and battened it down. The deluge then brought such massive destruction that even the gods were frightened by it. After the week of storm all of mankind had returned to clay. The ship came to a halt on Mt. Nisir, and on the seventh day Utnapishtim sent forth a dove, which went forth but came back. Then he sent forth a swallow, which went and came back, and then finally he sent forth a raven, which did not come back. Utnapishtim then sacrificed to the gods, who had repented their hasty destruction of mankind, and they came crowding around the sacrifice like flies. Although Enlil was at first still angry that his plan to destroy mankind had been thwarted, the rest of the gods were grateful that man had been saved, and Enlil thereupon rewarded Utnapishtim and his wife by making them like gods, giving them eternal life. Utnapishtim concludes his recitation of the flood by admonishing Gilgamesh that his story is unique and that Gilgamesh cannot hope to find immortality by following in Utnapishtim’s path (Gilgamesh XI: 197–198): “But now who will call the gods to Assembly for your sake, so that you may find the life that you seek?”

The nature of the story as “Utnapishtim’s tale” colors the recitation of the flood episode and makes it fundamentally different from the Biblical flood story. Utnapishtim can tell only those parts of the story that he knows, and he leaves out those aspects that do not concern him or fit his purpose. For example, Utnapishtim tells us nothing about the reasons that the gods brought the flood. This lapse is dictated by the literary format: Utnapishtim may not know the reason for the flood, or he may not record it because it is irrelevant to his purpose, which is to recount how he became immortal. Similarly, the only event after the flood about which Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh is the convocation of the gods that granted him immortality. The flood story in the Gilgamesh epic is essentially the personal tale of the adventure of one individual and the flood’s effect on him. The flood itself is therefore emptied of any cosmic or anthropological significance. The flood stories in Genesis and in Gilgamesh are, thus, far different structurally from each other so that the ideas in the two versions of the stories cannot be usefully compared.

Nor can the Sumerian flood story serve as the basis for independent meaningful comparison with the Bible for it has survived only in a very fragmentary state. The first 38 lines are missing, and there are long gaps in the narrative. As a result the outlines of the story must be reconstructed from the other texts, particularly from the Atrahasis Epic. Enough remains of the Sumerian text to indicate that we are dealing with the same basic tale of a hero (here called Ziusudra) who survived the flood and was thereafter made immortal, but the extensive gaps in the narrative mean that the composition cannot be analyzed as an independent unit.

The most recently discovered Babylonian text, the Atrahasis Epic, provides us with the most meaningful and instructive comparison with the Biblical Flood story.

The Atrahasis Epic presents the flood story in a context comparable to Genesis. Both are primeval histories.

The Atrahasis Epic begins with a description of the world as it existed before man was created: “When the gods worked like man … ” At this time, the universe was divided among the great gods, with An in possession of the heavens, Enlil the earth and Enki the great deep. Seven other gods established themselves as the ruling class, while the rest of the gods provided the work force. These working gods, whose “work was heavy, (whose) distress was much,” dug the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and then rebelled, refusing to continue to work. On the advice of the wise god, Enki, the gods decided to create another creature to do the work, and Enki and the mother goddess created man from a mixture of clay and the flesh and blood of a slain god. The slain god was “We-ilu, a god who has sense,”; from this characteristic of We-ilu, man was to possess rationality.

This epic, ancient though it is, is already the product of considerable development. The author has utilized old motifs and has united them into a coherent account of Man’s beginnings. The purpose of Man’s creation is to do the work of the gods, thus relieving the gods of the need to labor. In the Atrahasis Epic, the creation of man causes new problems. In the words of the Epic (I 352f. restored from II 1–8):

Twelve hundred years [had not yet passed]

[when the land extended] and the peoples multiplied.

The [land] was bellowing [like a bull].

The gods were disturbed with [their uproar].

[Emil heard] their noise

[and addressed] the great gods.

The noise of mankind [has become too intense for me]

[with their uproar] I am deprived of sleep.

To stop the noise created by too many people, the gods decide to bring a plague. Enki advised man to bring offerings to Namtar, god of the plague, and this induces him to lift the plague. Twelve hundred years later, the same problem again arises (Tablet II 1–8): The noise from so many people disturbs the gods. This time the gods bring a drought, which ends when men (upon Enki’s advice) bribe Adad to bring rain.

Despite the fragmentary state of Tablet II, it seems clear that the same problem recurs. This time the gods bring famine (and saline soil).

However, this does not end the difficulties either. Each time the earth becomes overpopulated. At last Enlil persuades the gods to adopt a “final solution” (II viii 34) to the human problem, and they resolve to bring a flood to destroy mankind. Their plan is thwarted by Enki, who has Atrahasis build an ark and so escape the flood. After the rest of mankind has been destroyed, and after the gods have had occasion to regret their actions and to realize (by their thirst and hunger) that they need man, Atrahasis offers a sacrifice, and the gods come to eat. Enki then presents a permanent solution to the overpopulation problem. The new world after the flood is to be different from the old; Enki summons Nintu, the birth goddess, and has her create new creatures who will ensure that the old problem does not arise again. In the words of the Epic (III vii 1):

In addition, let there be a third category among the peoples,

Among the peoples women who bear and women who do not bear.

Let there be among the peoples the Pasittu-demon to snatch the baby from the lap of her who bore it.

Establish Ugbabtu-women, Entu-women and Igistu-women

And let them be taboo and so stop childbirth.

Other post-flood provisions may have followed, but the text now becomes too fragmentary to read.

Despite the lacunae, the structure presented by the Atrahasis Epic is clear. Man is created; there is a problem; remedies are attempted but the problem remains; the decision is made to destroy man; this attempt is thwarted by the god Enki; a new remedy is instituted to ensure that the problem does not arise again. The problem that arose and that necessitated these various remedies was overpopulation.5 Mankind increased uncontrollably, and the methods of population control that were first attempted (drought, pestilence, famine) only solved the problem temporarily. This overpopulation led to an attempt at complete destruction (the flood). When this failed, permanent countermeasures were introduced by Enki to keep the size of the population down.

The myth tells us that such social phenomena as non-marrying women, and such personal tragedies as barrenness and stillbirth (and perhaps miscarriage and infant mortality) are in fact essential to the very continuation of man’s existence, for humanity was almost destroyed once when the population got out of control.

This Babylonian tale, composed no later than 1700 B.C. points out what, by the clear logic of hindsight, should have been obvious to us all along: there is an organic unity between the creation story and the flood story.

The structure of the Atrahasis Epic also tells us to focus our attention not on the deluge itself but on the events immediately after the rains subside. In Genesis, as in Atrahasis, the flood came in response to a serious problem in creation, a problem which was rectified immediately after the flood. A study of the changes that God made in the world after the flood gives a clearer picture of the conditions prevailing in the world before the flood, of the ultimate reason that necessitated the flood which almost caused the destruction of man, of the essential differences between the world before the flood and the world after it, and thus of the essential prerequisites for the continued existence of man on the earth.

The flood story in Genesis, unlike the Babylonian flood story we have just looked at, is emphatically not about overpopulation. On the contrary, God’s first action after the flood is to command Noah and his sons to “be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth” (Genesis 9:1). This echoes the original command to Adam (1:28). The repetition of this commandment in emphatic terms in Genesis 9:7 (“be fruitful and multiply, swarm over the earth and multiply in it”) makes it probable that the Bible consciously rejected the underlying theme of the Atrahasis Epic, which was that the fertility of man before the flood was the reason for his near destruction.

It is not surprising that Genesis rejects the idea of overpopulation as the reason for the flood, for the Bible does not share the belief of Atrahasis and some other ancient texts that overpopulation is a serious problem. Barrenness and stillbirth (or miscarriage) are not considered social necessities, nor are they justified as important for population control. On the contrary, when God promises the land to Israel he promises that “in your land women will neither miscarry nor be barren” (Exodus 23:26). The continuation of this verse, “I will fill the number of your days,” seems to be a repudiation of yet another of the “natural” methods of population control, that of premature death. In the ideal world which is to be established in the land of Israel there will be no need for such methods, for overpopulation is not a major concern.

This is the essential relevance of the Atrahasis Epic. It can tell us that structurally the creation and the near-destruction by the flood are related, that the flood was intended to cure a problem which arose from the original creation, that a new creation (but with a difference) was needed. It can teach us that to understand the meaning of the Biblical flood story, we must focus not on the deluge itself, but on the events immediately after the flood. In that way we can learn how the world changed after the flood, and that in turn will identify the problem in the original creation which the flood was intended to cure.

But the problem with the original creation in the Atrahasis Epic was clearly not the problem in the Biblical creation story. The Atrahasis Epic tells us only how to look, not what we shall find.

To identify the problem in the original creation in Genesis, we must look to Genesis, not to the Atrahasis Epic; but, as the Atrahasis Epic tells us, we must begin our search by exploring how the world changed after the flood.

After the Genesis flood, God offers Noah and his sons a covenant in which God promises never again to bring a flood to destroy the world. He gives the rainbow as the token of this promise. At this time, God gives Noah and his sons several laws. The difference between the ante- and post-diluvium worlds can be found in these laws. These laws are thus the structural equivalent of the new solutions proposed by Enki to the overpopulation problem in the Atrahasis Epic. In Atrahasis the problem in man’s creation was overpopulation, and the solutions proposed by Enki are designed to rectify this problem by controlling and limiting the population. In the Bible the problem is not overpopulation, but “since the devisings of man’s heart are evil from his youth” (Genesis 8:21), God must do something if he does not want to destroy the earth repeatedly. This something is to create laws for mankind, laws to ensure that matters do not again reach such a state that the world must be destroyed.a

Traditionally, the explanation for the Biblical flood is man’s wickedness. And, indeed, Genesis states explicitly that God decided to destroy the world because of the wickedness of man (Genesis 6:5–7), suggesting that God decided to destroy the world as a punishment for man’s sins. However, this is an unsatisfactory explanation—for several reasons. First, it creates serious theological problems: is it proper for God to destroy all life on earth because of man’s sins? Second, this traditional explanation creates what appears to be a paradox: after the flood, God decides never again to bring a flood (Genesis 8:21); the reason for this decision is “the wickedness of man”. Since the evil nature of man is presented after the flood as the reason for God’s vow never again to bring a flood, we should not infer that God brought the flood as a punishment because man was evil.

This seeming paradox is resolved, however, when we realize that the granting of laws after the flood was a direct response by God to the problem posed by man’s evil nature. This resolves the apparent paradox between the statement that the wickedness of man somehow caused the flood and the statement that the wickedness of man caused God to take steps to ensure that he will never again have to bring a flood.

However, we still have not answered the question of why the flood was necessary, why God could not simply have announced a new order and introduced laws to mankind without first destroying almost all of humanity.

This problem does not arise in the Babylonian flood stories, where there is a clear distinction between the gods who decide to bring a flood (Enlil and the council of the gods) and the god who realized the error of this decision, saved man and introduced the new order (Enki). The problem is quite serious, however, in the monotheistic conception of the flood in which the same God decides to bring the flood, saves man, and resolves never to bring a flood again. If God is rational and consistent in his actions, there must have been a compelling reason that necessitated the flood. “Punishment” is not enough of a reason, for it not only raises the question of God’s right to punish all the animals for the sins of man, but also raises the serious issue of God’s right to punish man in this instance at all; if man has evil tendencies, and if he has not been checked and directed by laws, how can he be punished for simply following his own instincts? The flood cannot simply have been brought as a punishment, and its necessitating cause must lie in the particular nature of the evil which filled the world before the flood.

The best way to find out the nature of the evil is to look at the solution given to control the evil, that is, to the laws given immediately after the flood.

According to Genesis 9, God issued three commandments to Noah and his sons immediately after the flood: (1) He commanded man to be fruitful, to increase, multiply and swarm over the earth; (2) He announced that although man may eat meat, he must not eat animals alive (or eat the blood, which is tantamount to the same thing—Genesis 9:4); and (3) He declared that no one, neither beast nor man, can kill a human being without forfeiting his own life; he shall be executed: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed.b

The significance of the first commandment (that of fertility) has already been mentioned: it is an explicit and probably conscious rejection of the Babylonian idea that the cause of the flood was overpopulation and that overpopulation is a serious problem.

Together, the other two commandments introduce a very clear differentiation between man and the animal kingdom: man may kill animals for food (while observing certain restrictions in so doing), but no one, whether man or beast, can kill man. The reason for this “Absolute Sanctity of Human Life” is given in the text: “For man is created in God’s image” (Genesis 9:6). Taken independently, these two commandments—the prohibition against eating blood (and the living animal) and the declaration of the principle of the inviolability of human life with the provision of capital punishment for murder—embody two of the basic principles of Israelite law.

The Bible views blood as a very special substance. Israel is repeatedly enjoined against eating the blood of animals (Genesis 9:4; Leviticus 3:17, Leviticus 7:26, Leviticus 17:10–14; Deuteronomy 12:16 and Deuteronomy 12:23–24). This prohibition is called an eternal ordinance (Leviticus 3:17), and the penalty for eating blood (at least in the Priestly tradition)c is karet, which is some form of outlawry, whether banishment or ostracism (Leviticus 7:27; Leviticus 17:10, Leviticus 17:14). The reason for this strict prohibition is explicit: the spirit (nefesh) of the animal is in the blood (Leviticus 17:11, Leviticus 17:14; Deuteronomy 12:23). The greatest care must be exercised in the eating of meat. According to the Priestly tradition, slaughtering of animals (other than creatures of the hunt) can only be done at an altar. Failure to bring the animal to the altar was considered tantamount to the shedding of blood (Leviticus 17:4). The sprinkling of the animal’s blood upon the altar served as a redemption (Leviticus 17:11). In Deuteronomy, where the cult is centralized and it is no longer feasible to bring the animals to an altar, permission is given to eat and slaughter animals anywhere. However (as with the animals of the hunt in Leviticus), care must be taken not to eat the blood, which should be poured upon the ground and covered (Deuteronomy 12:24).

The idea expressed in the third commandment to Noah and his sons—the inviolability of human life—is one of the fundamental axioms of Israelite philosophy, and the ramifications of this principle pervade every aspect of Israelite law and distinguish it dramatically from the other Near Eastern legal systems with which it otherwise has so much in common. In Israel, capital punishment is reserved for the direct offense against God and is never invoked for offenses against property. The inverse of this is also true; the prime offense in Israel is homicide, which can never be compensated by the payment of a monetary fine and can only be rectified by the execution of the murderer.

Despite the importance of this principle, if we look at the world before the flood, it is apparent that this demand for the execution of murderers is new in the post-flood world. Only three stories are preserved in Genesis from the ten generations between the expulsion from the Garden of Eden and the bringing of the flood. Two of these, the Cain and Abel story (Genesis 4:1–15) and the tale of Lemech (Genesis 4:19–24) concern the shedding of human blood. In the first tale, Cain, having murdered his brother Abel, becomes an outcast and must lose his home. However, he is not killed; in fact he becomes one of “God’s protected” and is marked with a special sign on his forehead to indicate that Cain’s punishment (if any) is the Lord’s and that whoever kills him will be subject to seven-fold retribution. The second story—that of Lemech five generations later—also concerns murder, for Lemech kills “a man for wounding me and a young man for hurting me,” (Genesis 4:23). Lemech, too, is not killed and claims the same protection that Cain had, declaring that as Cain was protected with sevenfold retribution, he, Lemech, will be avenged with seventy-sevenfold (Genesis 4:24).

The main difference between the world before the flood and the new order established immediately after it is the different treatment of murderers. The cause of the flood should therefore be sought in this crucial difference.

Murder has catastrophic consequences, not only for the individuals involved, but for the earth itself, which has the blood of innocent victims spilled upon it. As God says to Cain after Abel’s murder (Genesis 4:10–12):

Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the soil. And now you are cursed by the earth which opened her mouth to receive the blood of your brother from your hand. When you till the ground it shall no longer yield its strength to you; a wanderer and a vagabond you will be on the earth.

The innocent blood which was spilled on it has made the ground barren for Cain, who must therefore leave his land and become a wanderer.

This process of the cursing and concomitant barrenness of the ground had become widespread by Noah’s time. Noah’s name is mentioned for the first time in the Bible (Genesis 5:29) in a genealogy. There we are told that he “will provide us relief from our acts and from the toil of our hands, as a result of the ground which the Lord has placed under a curse.” The very name of Noah is related to the conditions which caused the flood, the “cursing” of the ground; Noah’s role somehow alleviates that condition. “This one will provide us relief” (Genesis 5:29).

By the generation of the flood, the whole earth has become polluted. “The earth was corrupt” and filled with hamas (Genesis 6:11). The Revised Standard Version translates hamas as violence; the new Jewish Publication Society translation, as injustice. The wide range of meanings of the word hamas in the Bible encompasses almost the entire spectrum of evil. In Genesis, the antediluvian earth is filled with hamas; the resultant pollution prompts God to bring a flood to physically erase everything from the earth and start anew. The flood is not primarily an agency of punishment (although to be drowned is hardly a pleasant reward), but a means of getting rid of a thoroughly polluted world and starting again with a clean, well-washed one. Then, when everything has been washed away, God resolves (Genesis 8:21):

Never again will I curse the ground because of man, for the devisings of man’s heart are evil from his youth, and never again will I destroy all the living creatures that I have created.

God goes on to give Noah and his sons the basic laws, specifically the strict instructions about the shedding of blood in order to prevent the earth’s becoming polluted again.

The idea of the pollution of the earth is not a vague metaphor to indicate moral wrongdoing. On the contrary, in the Biblical worldview, the murders before the flood contaminated the land and created a state of physical pollution which had to be eradicated by physical means (the flood).

Although this concept may seem strange to us, it is not surprising to find it here in the cosmology of ancient Israel, for Israel clearly believed that moral wrongdoings defile physically. This is explicitly stated with respect to three sins—murder, idolatry, and sexual abominations—and it is interesting to note that these are the three cardinal sins for which a Jew must suffer martyrdom rather than commit them (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 74a). These are mentioned in Acts as offenses from which all the nations must refrain (Acts 15:20). These three offenses are given by Rabbi Levy in Genesis Rabbah (31:16) as the explanation of hamas as used in the Genesis flood story; and these (together with the non-observance of the sabbatical year) are given in the Mishna as the reasons that exile enters the world (Avot 5:8).

According to Biblical tradition, the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Canaan had defiled the land with the sexual abominations enumerated in Leviticus 18. As a result, God had punished the land (Leviticus 18:25), and the land had therefore vomited up the inhabitants which had defiled it. For this reason, Israel is admonished not to commit these abominations and defile the land, lest it vomit them out in the same way (Leviticus 18:24–28). Later, Israel is told that it has defiled the land (Jeremiah 2:7) and that because Israel defiled the land with their idols and because of the blood which they spilled upon the land, God poured his fury upon them (Ezekiel 36:18).

The most serious contaminant of the land is the blood of those who have been murdered; the concept of “blood guilt” is well known in Israelite law. Because of the seriousness of the crime of murder, and perhaps also because of the mystical conception of blood in Israelite thought, the blood of the slain physically pollutes the land.

The shedding of human blood was of concern to the whole nation. Israel was enjoined against this blood guilt pollution and was admonished neither to allow compensation for murder, nor even to allow an accidental murderer to leave a city of refuge, for by so doing he would cause the land of Israel to become contaminated:

You shall take no ransom for the life of a murderer who is deserving of death. He shall be executed. You shall take no ransom to (allow someone to) flee a city of refuge or to (allow someone to) return to live in the land before the priest’s death. You shall not pollute the land that you are in, for the blood will pollute the land, and the land may not be redeemed for blood spilled on it except by the blood of the spiller. You shall not contaminate the land in which you are living, in which I the Lord am dwelling among the children of Israel (Numbers 35:31–34).

The idea of the pollution of the earth by murder, of the physical pollution caused by “moral” wrongs such as sexual abominations and idolatry, underlies much of Israelite law. The author of Genesis 1–9 has reinterpreted the cosmology and the early history of man in light of these very strong concepts. He has used a framework that is at least as old as the Epic of Atrahasis and the framework of the primeval history of Creation-Problem-Flood-Solution. But the Biblical author has retold the story to illuminate fundamental Israelite ideas, that is, the Biblical ideals that law and the sanctity of human life are the prerequisites of human existence upon the earth. The Biblical flood was brought to cleanse the earth of its blood guilt, of its affront to the sanctity of human life. When the land was cleansed, God gave Noah and his sons basic laws intended to prevent the future pollution of the earth.

This article is an adaptation written especially for Biblical Archaeology Review of an earlier article which appeared in Biblical Archaeologist (December 1977).

MLA Citation

Footnotes

While this passage from Genesis 8:21 suggests that man’s nature is basically evil, other Biblical passages do not take such a negative view of man, e.g. Psalm 8:4–5 “what is man, that thou art mindful of him? And the son of man that thou visitest him? For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels, and hast crowned him with glory and honour”. Even Genesis 1:8 has been interpreted to mean that the evil inclination does not come to a man until he becomes a youth (ten years old). according to the rabbinic commentary, Midrash Tanhuma Bereshit 1.7, it is man who raises himself to be evil. This, according to the Midrash, is the plain meaning of the statement in Genesis 8:21 that “the imagination of man’s heart is evil from his youth.” Obviously, the controversy about man’s basic nature is an old one. Genesis 1:8 clearly comes down on the darker side of this controversy. Whether from birth or from the age of ten, man’s nature is inherently evil; he is naturally prone to violent and unrighteous acts. This view of man logically entails a recognition that man cannot be allowed to live by his instincts alone, that he must be directed and controlled by laws, that in fact, laws are the sine qua non of human existence. It is for this reason that God’s first act after the flood is to give man law.

The oral tradition of Israel (as reflected in the rabbinic writings) has developed and expanded the laws given to Noah and his sons after the flood into a somewhat elaborate system of “the seven Noahide commandments”. The traditional enumeration of these is the prohibition of idolatry, blasphemy, bloodshed, sexual sins, theft, eating from a living animal, and the commandment to establish legal systems. Additional laws are sometimes included among the commandments to Noah and his sons, and the system of Noahide commandments can best be understood as a system of universal ethics, a “Natural Law” system in which the laws are given by God. Genesis itself, however, does not contain a list of all seven of these commandments.

Endnotes

J. Laessoe, “The Atrahasis Epic, A Babylonian History of Mankind”, Biblioteca Orientalia 13, pp. 90–102 (1956).

Most recently edited by Miguel Civil in Lambert and Millard, Atrahasis: the Babylonian Story of the Flood, Oxford, 1969.

See Anne Kilmer, “The Mesopotamian Concept of Overpopulation and Its Solution as Represented in the Mythology”, Orientalia 41, pp. 160–177 (1972), and William J. Moran, “The Babylonian Story of the Flood (review article)”, Biblica 40, pp. 51–61 (1971), who working independently, also demonstrated that the problem which concerned the Babylonian gods was overpopulation.