Well, one thing it’s not—or at least not only—is a high place. Jerome’s fourth-century Latin translation of the Bible (called the Vulgate) rendered bamah as excelsus, which led to the popular English translation “high place.” Unfortunately, this translation has for centuries colored our understanding of numerous Biblical passages.1 Bamah appears over 100 times in the Bible, primarily referring to a cultic site of some sort. Exegetes and scholars have defined it in various ways:

• A primitive open-air installation on a natural hilltop equipped with some combination of asheraha (sacred pole),

• An artificially raised platform upon which religious rites take place.3

• A sacrificial altar.4

• A mortuary installation.5

Bamot are often perceived as the site of rather bawdy Canaanite rituals. According to the Bible, the chronically backsliding Israelites revived these practices, rather than adhere to the Jerusalem-centered, “normative” Yahwism (the worship of the Israelite god Yahweh).6

The Hebrew root BMH has cognates in several Semitic languages, but these cognates have no sacred associations. In Ugaritic,b the cognate means the back of a body; in Akkadianc the singular likewise means back, but the plural refers to terrain, possibly hilly.7

From all this, it can be concluded that the many attempts to describe the bamah have not created a consensus about what a bamah was. A new approach seems in order.

I would like to try to understand the concept of the bamah by using the methods of social science. First I want to examine the bamah in the context of the social structures within which it was embedded, as they are described in the Bible.8 This will provide a theoretical model for the bamah against which archaeological data can be tested. If this archaeological evidence sufficiently mirrors the model, then we will have correctly assessed the function of the bamah and accurately identified a number of actual Israelite bamot (the plural).9

For the most part, the Hebrew Bible vilifies worship at bamot and joyfully lauds their destruction. The Biblical editors now known as the Deuteronomistic historians (who compiled and edited much of the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings late in the seventh century B.C.E.) advocated a Jerusalem-centered religion. They wanted sacred rituals to be conducted only in Jerusalem, at the Temple, in which they claimed that Yahweh dwelled (Deuteronomy 12:1–7; cf. 2 Kings 23:27), and not in every village and hilltop site. They made their case so persuasively that even today bamot are often thought to have been sites of gross apostasy, vestigial elements of Canaanite paganism that insidiously recurred because Israelites and Judahites did not remain true to their Yahwistic faith.

Nevertheless, an alternate perspective is interwoven throughout the Biblical text.

The earliest—and fullest—references to the bamah come from the tribal period, the era of the Judges.10 Appropriately for a tribal confederation, the bamot (and other places of worship) were essentially local phenomena. When young Saul looks for a seer to help him find his father’s lost asses, he comes to Samuel, who officiates at a bamah in or near an unnamed city in the district of Zuph. We know this bamah was elevated, because Samuel “descends” from it to meet Saul (1 Samuel 9:11–25). (Don’t be jolted when you look up this passage and fail to find bamah in your English translation; the Hebrew word is variously translated “high place” [King James, Jerusalem Bible], “high-shrine” [New English Bible] and “shrine” [New Revised Standard Version, New Jewish Publication Society].)d Later, Samuel tells Saul to go a place called “the hill of God,” where he will see a procession of prophets coming down from a bamah (1 Samuel 10:5).

Israel underwent enormous changes in its political and social structure as it was transformed from a tribal confederation into a monarchy. During King David’s reign, in the tenth century B.C.E., Israel expanded from a small nation-state into an empire, as David first consolidated his power within Israel and then expanded his rule to nearby kingdoms north, west and east of Israel. Although David’s involvement in the construction of the Jerusalem Temple has been downplayed in the Bible, it is clear that he provided the creative energy behind its construction.11 He even organized the work force used by his son Solomon to build the Temple (1 Chronicles 22).

That David initiated construction of a centralized place of worship accords well with what is known about his other efforts at national consolidation.12 It seems logical that he would also move to increase his control over worship outside his capital city. To be sure, textual evidence for David’s involvement in the organization of religious practice outside of Jerusalem is elusive. In 1 Chronicles 15, we have a description of David’s organization of a large body of priests and Levites.13 Joshua 21 lists those Levitical cities that, it has been persuasively argued, originated in David’s reign.14 Taken together, these two chapters appear to describe a plan for the resettlement of Levites throughout the realm. The aim of this clerical reorganization, I would suggest, was the strengthening of national solidarity and the promotion of loyalty to the king through the promulgation of the official religion in outlying areas.15 Thus, the countryside bamot remained fundamental to Israelite life throughout David’s reign and even up to the time of Solomon’s construction of the Jerusalem Temple.

Before Solomon completed the Jerusalem Temple, we are told, the people “continued to offer sacrifices at bamot because no house had yet been built for the name of the Lord” (1 Kings 3:2). Solomon also offered sacrifices at bamot (1 Kings 3:3). At the bamah in Gibeon, the largest (or major) bamah, Solomon made a thousand burnt offerings; and there Yahweh appeared to Solomon in a dream (1 Kings 3:4–5).

As these references make clear, worship at bamot was an Israelite custom that prevailed during the period of the tribal confederations (the period of the Judges) and during the United Monarchy.

The Deuteronomistic historians’ great complaint about Solomon was that after the completion of the Temple, the only appropriate place for Yahwistic worship, Solomon nonetheless built bamot for his non-Israelite wives and for the gods of Sidon, Ammon and Moab (1 Kings 11:4–8). (David had previously conquered Ammon and Moab [2 Samuel 8:2, 12:26–31].) The eighth-century prophet Isaiah also mentions worship at bamot in Moab (Isaiah 15:2, 16:12). Sanctuaries dedicated to Milkom and Kemosh, gods of the Ammonites and Moabites respectively, were even built in the heart of Jerusalem, in order to obtain the cooperation of the Ammonite and Moabite peoples.16 Many of Solomon’s wives were acquired through diplomatic marriages or as spoils of war. The bamot constructed for these wives’ religious practices were likewise diplomatic concessions, to obtain the cooperation of the peoples represented by the wives.

After Solomon’s death the nation split in two—Israel in the north and Judah in the south. During the so-called Divided Monarchy, the situation was quite different, at least as seen through the eyes of the Deuteronomistic historians. Jeroboam, first king of the northern kingdom of Israel, constructed royal sanctuaries with golden calves at Bethel (Amos 7:13) and Dan17 in order to break the ties between his Israelite subjects and his rival in Judahite Jerusalem (1 Kings 12:25–30). Fearful that these royal shrines would not sufficiently ensure his people’s loyalty, Jeroboam also constructed bamot throughout his kingdom. A non-Levitical priestly group drawn from all classes of society was formed to officiate at them (1 Kings 12:31). The Biblical condemnation of Jeroboam may speak as much to the pro-Levitical stance of the Deuteronomistic redactors of the Book of Kings as to their hatred of the bamot.

Even in the southern kingdom of Judah, the royal cult in Jerusalem did not adequately meet the socio-political goals of the rulers. Judah’s monarchs therefore established bamot similar to those in the northern kingdom (2 Kings 23:5).

An episode from the end of the eighth century B.C.E. indicates that the bamot were still regarded as legitimate at that late date. In 701 B.C.E., Assyria invaded Judah. The Assyrian king Sennacherib sent several of his chief officers to Jerusalem to negotiate a peaceful resolution for his imperial designs (2 Kings 18:17–37; 2 Chronicles 32:9–19). Addressing both administrators and residents of the capital city, these officers argued that as a result of the apostasy of Hezekiah, king of Judah, Sennacherib had been chosen by Yahweh to redeem Israel. Among the charges hurled at the Judahite monarch was that he had destroyed the bamot—Yahweh’s bamot—and now insisted that Yahweh be worshiped exclusively in Jerusalem (scholars refer to this as Hezekiah’s reform). By doing this, argued Sennacherib’s men, Hezekiah had undermined devotion to the very god from whom he was now claiming support. The damaging potential of these charges was underscored by the Judahite ministers’ request that the Assyrian officers speak in Aramaic rather than Hebrew, so that Judahites within hearing distance would not understand the conversation.

Late in the seventh century B.C.E., Josiah, like Hezekiah before him, also instituted numerous cultic reforms in order to centralize worship of Yahweh in Jerusalem (2 Kings 23). (Scholars call this Josiah’s reform.) Pointedly, even after Josiah destroyed the bamot, the bamot priests did not worship in the Jerusalem Temple. Rather, they joined with others of their own clans, underscoring the somewhat independent position of the bamot priesthood within the residual tribal elements of the Judahite population (2 Kings 23:9). (Israel had been destroyed by the Assyrians in 721 B.C.E., and its population, deported [2 Chronicles 33:10–11].)

In short, two-tiered religious hierarchies were set up in Israel and in Judah. The first was the royal cult, celebrated in the north in Bethel and Dan and in the south in Jerusalem. It provided the monarchy with illusions of Canaanite-style grandeur and permanence and at the same time enforced a somewhat undesired centralization upon Israelite and Judahite worship. The second tier was the traditional bamot system of regional sites for worship. These bamot provided the people of Israel and Judah with access to local religious centers and at least partially neutralized otherwise disenfranchised and potentially fractious non-Levitical clergy by presenting them with alternative status positions.

From the anti-bamot stance adopted by the Deuteronomistic historians, one glimpses the tensions inherent in this dual-access approach to Yahwism. Over time, the bamot priesthood evidently grew increasingly independent of the royal clergy. At least in part to eliminate the threat they posed to royal authority, Hezekiah in the eighth century B.C.E. and later Josiah in the seventh century B.C.E., waged campaigns against the rural bamot, hoping to eradicate the bamot priesthood’s power base and to centralize worship in Jerusalem. These are the so-called religious reforms of Hezekiah and Josiah.

In summary, the Biblical record suggests that the bamah was for the most part an accepted place for Israelite worship, one that met the needs of the local Israelite and Judahite citizenry. At the same time, certain elements within the population, particularly the priestly and prophetic group whose traditions culminated in the work of the Deuteronomistic school, opposed the decentralizing tendency of the bamot and waged a sometimes successful campaign advocating the primacy of the Jerusalem Temple. The extent of their success is measured by the fact that the Biblical account of religion in Israel and Judah almost, but not quite, convinces us that bamot were not legitimate elements of Israelite and Judahite worship.

Turning to archaeology, a number of sacred structures and installations from the time of the Judges and from the United and Divided Monarchies have been discovered that provide physical evidence for the organization and practice of religion in Iron Age Israel.e

The earliest of the Israelite sacred places come from the 12th century B.C.E., the era of the Judges.18 Israeli archaeologist Amihai Mazar excavated a hilltop site (the so-called Bull Site) in Biblical Manasseh, where he found a sacred area composed of simple stone installations, including a

Another 12th-century hilltop cult place was excavated on Mt. Ebal by Israeli archaeologist Adam Zertal. Bones of numerous young male animals were recovered, together with a possible stone altar and other installations, all encircled by a stone wall. These discoveries, as well as Biblical references to an altar on Mt. Ebal during the era of the Israelite settlement (Deuteronomy 27:4–8; Joshua 8:30–31), indicate that this too was an open-air sacred site.20

Since the discovery of these sites in Manasseh and Mt. Ebal, scholars have debated whether they are in fact sacred places, and, if so, whether they are Israelite.f As we are learning, the process of Israelite settlement was slow and uneven. These two sacred hilltop installations are in regions that would soon be known as Israelite, and so it is likely that the people worshiping at them were themselves Israelites, or at least Israelites-to-be.

A regional cult center of the 12th to mid-11th centuries B.C.E. was excavated at Shiloh.g Although later construction destroyed the sanctuary itself, storage and residential structures associated with the sacred complex were uncovered. Broken pottery, animal bones and fragments of vessels depicting cultic motifs were found in these rooms. Much of the tell was filled by the sacred complex, leaving little room for other kinds of activities.21 The archaeological evidence thus supports the Biblical description of Shiloh as a pilgrimage center serving Israelites living throughout the central hill country (see, for example, Judges 21:12; 1 Samuel 1:3).

At Hazor, a small cultic structure was found in the 11th-century B.C.E. Israelite village. A ceramic jar filled with bronze objects was found under the floor of this small, bench-lined room. Other cultic objects, including incense stands, were found in paved areas (courtyards or rooms) around the main chamber.22

The contents of the buried jar, all bronze, include a helmeted male figure, weapons, and broken pieces of worked and alloy metal.23 The hoard of bronzes was eventually hidden, when the Israelite village was abandoned late in the 11th century B.C.E.

As a group, then, the excavated sacred sites from the period of the Judges, the era of the Israelite settlement in Canaan, are somewhat eclectic. A pilgrimage sanctuary (Shiloh) was used by settlers in the hill country, but they, or others, also worshiped at open-air shrines (like the Bull Site and Mt. Ebal) and, slightly later, in at least one village sanctuary (Hazor). This diversity is precisely what our model leads us to expect from the disparate tribal groups involved in the lengthy process of settling down and unifying.

Once a king was installed in Jerusalem, the constellation of sacred places in which Israelites worshiped began to change. Sanctuaries from the tenth century, the period of the United Monarchy, display an increasing degree of uniformity, as reflected in their architecture, in the cultic artifacts they contained, and in the choice of locations. As we would have expected from our analysis of the Biblical text, the village sanctuary becomes the prevalent place of worship in Israel, but it is also increasingly a tool of the monarchy.

At Megiddo, two tenth-century sanctuaries were constructed as part of a massive Solomonic building project. Both of these sanctuaries (Building 338 and Shrine 2081) were built of ashlar masonry, decorated with proto-Ionic capitals and situated so that their rear facades marked the upper periphery of the site.

David Ussishkin recently noted the many resemblances in cultic paraphernalia between the two Solomonic sanctuaries at Megiddo.24 These included limestone horned altars and round limestone offering-tables and stands, basalt three-legged mortars with pestles, and small juglets. Square ceramic model shrines and a primitive male figure were found in Building 338, while Shrine 2081 contained a round stand on a fenestrated base, burned grain near the altars and a bowl of sheep/goat astragali (knuckles).

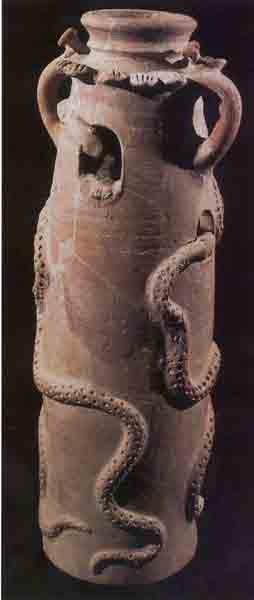

Taanach, like Megiddo, was first home to a small Israelite community in the decades of the Davidic monarchy. Unfortunately, the architectural elements of the subsequent Solomonic-period cult structure were poorly preserved; however, its scale, contents and location near a cultic oil installation suggest public usage. Among the objects found in association with this multi-roomed sanctuary were iron knives, astragali, a figurine mold, numerous ceramic vessels including some with specialized cultic functions, and two ceramic stands decorated with elaborate cultic motifs.25

Cult Room 49 at Lachish is a small bench-lined sanctuary dating from the tenth century B.C.E. Its ceramic assemblage and cultic objects, among which are a limestone horned altar and ceramic stands, resemble those from the Megiddo and Taanach sanctuaries. Small and simply constructed, Cult Room 49 was nonetheless the finest building in this United Monarchy era settlement.26

The destruction of the last independent Philistine city at Tel Qasile (stratum X) early in the tenth century has been attributed to David. Subsequent strata (IX–VIII) represent the settlement of the United Monarchy, during which time the stratum-X sanctuary was at least partially reconstructed. The reconstructed temple was surrounded on three sides by a large lime-paved courtyard in which were a large stone altar and two ovens.27

At this time, Qasile was a port city of the United Monarchy. Amihai Mazar suggests that the tenth-century rebuilding of the earlier sanctuary indicates its continuing importance for the indigenous Philistine inhabitants of the city, some of whom remained after the Israelite conquest. But nothing in its later use seems incompatible with Israelite worship; it is quite possible that, as this area became residential, the rebuilt sanctuary served the new Israelite inhabitants of the city.

At Beth-Shean, the southern temple of the tenth century was part of a large fortress complex, the initial construction of which had taken place during David’s reign. Numerous cult objects, in particular exotic ceramic stands, were found on the sanctuary floor.28 Although stelae honoring three New Kingdom Egyptian monarchs stood near the southern temple until Shishak’s rampage through Israel in 918 B.C.E.,29 it is difficult to imagine a city within Israel’s borders being fortified by other than Israelite forces during the reigns of either David or Solomon. Thus, the southern temple at Beth-Shean should be considered an Israelite sanctuary of the United Monarchy.

Mound A at Tell el-Mazar, in the Jordan Valley, is a late eleventh- to late tenth-century extramural sanctuary consisting of three contiguous chambers bordered on the south by a large courtyard. A stone bench lined two walls of the easternmost chamber, which also contained an embedded stone basin and a deep bell-shaped pit. Numerous late tenth-century vessels, including two chalices and a fenestrated ceramic stand, were found in the eastern room. Several ovens and a stone table were set intothe courtyard.30

At Makmish, a small site on the Sharon Plain, as at Tell el-Mazar, the sanctuary was extramural. The site contained a large, enclosed, open-air cultic structure dated to the later part of the tenth century. Within the enclosure were a central altar and several flat-lying stones upon which sacrifices could be made and sacred meals prepared and eaten.31

Tel ‘Amal, near Beth-Shean, was a farming village as well as a center for textile dying and weaving. It was founded during David’s reign (stratum IV) and incorporated by Solomon (stratum III) into his 20th administrative district. A three-room building was used for domestic and cultic purposes, and for workshop space. Religious artifacts at the site include votive vessels, chalices, a tambourine-playing figurine and ceramic and stone cultic stands. One stone tripod was decorated with zoomorphic and botanical motifs.32 At Tel ‘Amal, no single structure or room can be identified as exclusively cultic. Rather, religious, industrial and domestic activities intermingled within one structure. This admixture underscores the complex interplay between religion and industry, between the “state” and private lives, that was so typical of religion in Iron Age Israel.

While every sacred site of the United Monarchy displays unique features, as a group they share some general characteristics. Except for the Jerusalem Temple, most United Monarchy sanctuaries were in villages or towns, often in peripheral locations where ethnically divergent populations may have required special attention to draw them into the Israelite nation. Although the architectural features of the sanctuaries are not always clear and they often reflect the requirements of their individual locations, their scale in proportion to other structures at the sites generally reflects the sanctuaries’ local as well as national importance. Assemblages of cultic artifacts differ in detail, but often include limestone altars and limestone or ceramic stands. These, then, are the bamot of the United Monarchy.

Despite many Biblical allusions to worship at bamot during the Divided Monarchy, very few sacred sites from this period have been excavated. Given the prominence of the Jerusalem Temple and its priesthood in the rather small kingdom of Judah, it may not be coincidental that excavated sacred sites of the ninth through seventh centuries have been found in the northern kingdom of Israel.

We have already mentioned that as a result of his campaign to consolidate his rule over the new kingdom of Israel and to ensure the loyalty of its citizens, Jeroboam built religious centers at Dan in the northern part of his kingdom and at Bethel in the southern part of his kingdom (1 Kings 12:25–33).33 No archaeological evidence for the royal cult center at Bethel has been found. Near the spring at Dan, however, excavators found a cult center consisting of three main parts. The first is an enormous raised platform that may originally have supported a sanctuary.34 Finds associated with the platform include seven-spouted lamps, an Astarte figurine and a four-horned altar.35. The second part of the Dan cultic complex is an open area in which the main sacrificial altar is located. In it, several small rooms served both religious and administrative purposes.36. Finally, a press for the preparation of olive oil for ritual purposes was found in the northern part of the sacred compound.37 Four unusual faience figurines were uncovered in and around this oil press.38

Tel Kedesh, located between Megiddo and Taanach, may have been the Kedesh of the settlement-era story of Deborah in Judges 4. The scale and contents of one building from the early ninth-century B.C.E. town at Tel Kedesh suggest sacred functions. In particular, a number of jar bases were set into its floor, near a four-horned limestone altar.39.

Tell es-Sa‘idiyeh is a late ninth- to early eighth-century B.C.E. walled town in the central Jordan Valley, consisting primarily of small two-roomed houses haphazardly set along narrow streets. In contrast, Building 64 is a three-roomed structure, the contents and installations of which suggest both domestic and cultic activities. An arrowhead lay on a plastered platform in one room, and a three-legged ceramic incense burner surrounded by ashes and charcoal rested in one of the two depressions in the platform. Along with an assortment of utilitarian objects, other unique finds from Building 64 include additional incense burners, a collection of nine shells and the only lamps found in this stratum.40

At Arad a sanctuary was constructed in the northwestern corner of the Iron Age royal fortress. A large altar of unhewn stones, topped with a flint slab, stood in the center of the sacred courtyard. This courtyard opened into a narrow, bench-lined chamber. Two stone pillars, two small limestone incense altars and offering benches flanked the entrance to the niched recess (Holy of Holies) at the back of the sanctuary. A stela decorated with red paint stood on a small platform within the Holy of Holies, while two crude flint slabs were plastered into its back wall.41 Cultic paraphernalia, including a decorated ceramic incense burner, two shallow bowls inscribed with the Hebrew letters qop and kaf (an abbreviation for qodes kohanim, “set apart for [or holy to] the priests”), a stone basin and a small bronze figurine of a lion were found in and around the sanctuary. Kilns found near the entrance to the sanctuary are remains of the pottery workshop that supplied the sacred vessels.42

Ostraca (inscribed potsherds) possibly used for assigning temple duties at Arad bore names of members of priestly families known in Jerusalem at the time of Jeremiah and Ezra (Meremoth—Ezra 8:33, 1 Chronicles 9:12; Pashhur—Jeremiah 20:1), as well as Yahwistic names including Eshiyahu and Netanyahu. Other ostraca from Arad carried administrative entries, noting payments made to or by the priestly families of Korah (Numbers 16, 26:9–11) and Bezal(el) (Exodus 31:2).

All this evidence from Arad combines to depict a Yahwistic sanctuary in the royal fortress at Arad during the monarchical period.43 However, the date of that sacred structure is uncertain. The original date of tenth to late seventh centuries B.C.E.44 has recently been called into question. New analyses suggest that the sanctuary was constructed early in the seventh century B.C.E. and was destroyed a century later.45

A number of cultic objects found at Beersheba indicate that a religious structure was once part of this Iron Age city. A large horned altar of ashlars, found in a secondary context, was evidently used in the first centuries of the Divided Monarchy. However, the original setting for the altar, and for the religious structure that would have accompanied it, are subject to debate.46 Zoomorphic vessels, animal figurines and a krater bearing the inscription qds (holy) were found in several houses.47

Kuntillet ‘Ajrud is a mid-ninth- to mid-eighth-century B.C.E. caravanserai, located about 30 miles (50 km.) south of Kadesh-Barnea in the Sinai.h The installation at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud originally consisted of two buildings. The larger of the two buildings was not a typical Judahite fortress but rather a well-defended hostel and religious center. At its core was the “bench room” with decorated plastered walls and inscribed vessels.48 The religious expression attested to in these drawings and inscriptions is marked by its syncretistic nature, including particularly the worship of Yahweh, of Baal and of Asherah.49

Although the number of sacred sites from the Divided Monarchy is small and the sanctuaries differ in many respects, they share certain elements, as expected. These include limestone horned altars, metal and stone incense burners, an increasing number of inscriptions, benched rooms and a proximity to oil presses.

In summary, in the era of the Judges, the Israelites were an amalgam of clans and tribes that would soon coalesce into the nation of Israel. Religion and places of religious worship in that era were somewhat idiosyncratic, tailored to the customs and needs of individual worshiping groups. In this pre-monarchical era, the word bamah refers to a specific sacred place or structure. First Samuel 9:11–25 and 1 Samuel 10:5 suggest that bamot could be either within or outside of settlements. This ambiguity is clarified by examination of archaeological remains of religious structures from that period. As we have seen, they range from a built-up pilgrimage site (Shiloh) to open-air sanctuaries (Mt. Ebal and the Bull Site). Slightly later, a small village sanctuary (Hazor) points the way to the sorts of religious buildings that would come to typify the Israelite nation.

Extensive editing by the Deuteronomistic historians has obscured the United Monarchy’s policy of sanctuary construction. But if recent textual and archaeological discoveries are examined from the perspective of social science, this policy fits well with what is known about David’s and Solomon’s empire-building strategies. The tenth-century B.C.E. sanctuaries excavated throughout Israel were located at sites with Israelite occupation during the Davidic era. The Hebrew Bible attests to the monarchical bamah’s legitimacy in Yahwistic religion, to Solomon’s construction of bamot in Jerusalem, to the role of the bamah as a place of service for otherwise disenfranchised priestly groups and to its use by non-Jerusalemites. Thus, the tenth-century sanctuaries uncovered at Megiddo, Lachish, Qasile, Taanach and Beth-Shean are what we might expect: They are examples of the bamot that the Bible refers to in this period. At the same time, people continued their traditional practice of congregating and worshiping at extramural shrines or pilgrimage centers, such as those at Makmish and Tell el-Mazar.

During the United Monarchy, then, the bamah sanctuary of the period of the Judges was innovatively reformulated into an institution of social and religious control, a means of forging national unification from the disparate elements of the Israelite tribal coalition and the local conquered populations. The tenth-century B.C.E. bamot were constructed as part of a well-conceived plan to place religious practice in logistically vital centers under the scrutiny of the royal administration and to foster solidarity among the diverse elements that composed the newly formed nation-state of Israel.

During the Divided Monarchy, Jeroboam in the north and various unnamed rulers in the south pursued similar policies. Bamot, long since recognized as an institution of the state, were constructed at sites of special importance to the monarchy—in particular at Dan, Bethel and Arad. At the same time, worship took place at village sites (Kedesh and Tell es-Sa‘adiyeh, for example), along trade routes (Kuntillet ‘Ajrud) and in the open countryside (as noted in numerous Biblical passages). In this way, the rather eclectic traditions of the pre-monarchical period merged with those of the monarchical era, highlighting the texture and variety of the Israelite religious experience.

Certain Judean monarchs, most notably Hezekiah in the late eighth century and Josiah in the late seventh century, tried to enforce the authority of the Jerusalem Temple as they struggled against the tendency toward regional autonomy that the bamot fostered. This added yet another vital element to the already complex and fascinating picture of religion in ancient Israel.

(This article is a revision of a paper presented at the 1990 Annual Meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research, in New Orleans. I would like to thank William G. Dever and Susan Ackerman for their many lucid suggestions; at the same time I absolve them of any responsibility for the final product. The preparation of this article was made possible in part by a grant from the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture. Biblical Archaeology Today 1990 [Israel Exploration Society, 1993] was unpublished when this article was written.)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Ze’ev Meshel, “Did Yahweh Have a Consort?” BAR 04:03; André Lemaire, “Who or What Was Yahweh’s Asherah?” BAR 10:06; and Ruth Hestrin, “Understanding Asherah—Exploring Semitic Iconography,” BAR 17:05.

Akkadian is a Semitic language that was used in Mesopotamia as long ago as the third millennium B.C.E.

Elsewhere the New Jewish Publication Society translation renders the word as “open shrine” (1 Kings 3:2).

Contemporaneous sacred places belonging to non-Israelites, including the Philistines (at Ashdod and Miqne) and the Edomites (at Horvat Qitmit; see Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, “New Light on the Edomites,” BAR 14:02) have also been excavated.

See Aharon Kempinski, “Joshua’s Altar—An Iron Age I Watchtower,” and Adam Zertal, “How Can Kempinski Be So Wrong?” both in BAR 12:01; and Hershel Shanks, “Two Early Israelite Cult Sites Now Questioned,” BAR 14:01.

See Israel Finkelstein, “Shiloh Yields Some, But Not All, of Its Secrets,” BAR 12:01.

See “Cache of Hebrew and Phoenician Inscriptions Found in Desert,” BAR 02:01; Ze’ev Meshel, “Did Yahweh Have a Consort?” BAR 05:02; and André Lemaire, “Who or What Was Yahweh’s Asherah?” BAR 10:06.

Endnotes

Note Torczyner’s early counteractive statement: “I have tried to show that ‘bamot’ are not ‘high’ places but sacred buildings erected, both on high as in low places” (Harry Torczyner et al., Lachish I: Tel Lachish Letters [London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1938], p. 30). He continued by suggesting that the term bamah refers to a cultic building and to all the ritual objects found within it.

See, for example, R.A. Stewart Macalister’s interpretation of the Gezer Middle Bronze II standing stones as a high place, a Canaanite precursor of the Biblical bamah (The Excavation of Gezer, 3 vols. [London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1912], vol. 2, pp. 381–406).

See, for example, Avraham Biran, “To the God Who Is in Dan,” in Temples and High Places in Biblical Times, ed. Biran (Jerusalem: Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, 1981), pp. 142–145. Here, Biran discusses the enormous stone platform excavated in Divided Monarchy Dan. See also “Avraham Biran—Twenty Years of Digging at Dan,” BAR 13:04. Patrick D. Miller’s description of the bamah as, minimally, “a raised elevation, platform, or mound often alongside or near a sanctuary and set up primarily for the purpose of sacrifices” (“Israelite Religion,” in The Hebrew Bible and Its Modern Interpreters, ed. D.A. Knight and G.M. Tucker [Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985], p. 228) incorporates the idea of platform and several others. See also Patrick H. Vaughan, The Meaning of “Bama” in the Old Testament: A Study of Etymological, Textual and Archaeological Evidence, Society for Old Testament Study Monograph Series 3 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1974), p. 55. Vaughan specifies two types of bamot or “cultic platforms.” They are “truncated cones of some height; and low oblong ones which may also have had an altar standing on them.”

See Yigael Yadin, “Beer-sheba: The High Place Destroyed by King Josiah,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (BASOR) 222 (1976), p. 8; Menahem Haran, “Temples and Cultic Open Areas as Reflected in the Bible,” in Biran, ed., Temples and High Places, p. 33; and Haran, Temples and Temple-Service in Ancient Israel: An Inquiry into Biblical Cult Phenomena and the Historical Setting of the Priestly School (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1985), pp. 17–25.

See, for example, William F. Albright, “The High Place in Ancient Palestine,” Vetus Testamentum Supplement 4 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1957); Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969), p. 102; and, contra, W. Boyd Barrick, “The Funerary Character of ‘High Places’ in Ancient Palestine: A Reassessment,” Vetus Testamentum 25 (1975), pp. 565–595.

Rudolf Kittel, an early pioneer in the study of Israelite religion, considered the bamah to have been the place for the enactment of Canaanite cult. The later tendency of Israel to revert to Canaanite religious practices he likened to the allure of Catholicism (“pleasing both to the senses and to the imagination”) over and against the “sternly ethical” Protestantism of the Reformed Churches. The latter, in Kittel’s opinion, was closely aligned to the “serious form of worship” offered by the prophets (The Religion of the People of Israel, trans. R.C. Micklem [New York: Macmillan, 1925], pp. 34–35, 146).

This is the approach used by Yohanan Aharoni in his description of the Arad and other bamot temples as institutions “at the royal administrative and military centers dominating the [Israelite and Judaean] borders” (“Arad: Its Inscriptions and Temple,” Biblical Archaeologist 31 [1968], pp. 28–30).

The following comments of William G. Dever are most appropriate: “There seems to be a great deal of unnecessary confusion, not to mention skepticism, in our discipline about the use of social science ‘models’ in archaeology. Yet a model is simply a heuristic device, an aid in interpretation and understanding the basic evidence. It is, if you wish, a hypothesis to be tested against the evidence, and if necessary replaced by one that is more useful as new evidence becomes available. A model is simply a way of framing appropriate questions. And without doing that explicitly, I would argue that we can never hope to convert so-called archaeological ‘facts’ into true and meaningful data, data that can elucidate the complex cultural process in ancient Palestine” (“The Rise of Complexity in Palestine in the Early Second Millennium B.C.,” Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, 1990 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993). See also Norman Yoffee, “Social History and Historical Method in the Late Old Babylonian Period,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 102 (1982), pp. 347–348.)

See Leviticus 26:30 (in which Yahweh threatens to destroy Israelite bamot) and Numbers 33:52. Both of these are attributed to the Priestly School (Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible [New York: Summit/Simon and Schuster, 1987], pp. 252, 254), writing in the seventh or sixth century B.C.E.

Carol Meyers, “David as Temple Builder,” in Ancient Israelite Religion: Essays in Honor of Frank Moore Cross, ed. P.D. Miller, Jr., P.D. Hanson and S.D. McBride (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987), pp. 357–376.

The economic centralization of David’s empire as detailed in 1 Chronicles 27:25–31 has been documented by Michael Heltzer, “The Royal Economy of King David Compared with the Royal Economy in Ugarit,” Eretz-Israel 20 (1989), pp. 175–180 (in Hebrew). Agricultural produce and the breeding of livestock were managed according to specialized programs, subsequent to which goods were distributed according to state policy.

First Chronicles contains many texts relevant to the study of early monarchical Israel. See Baruch Halpern, “Sacred History and Ideology: Chronicles’ Thematic Structure—Indications of an Earlier Source,” in The Creation of Sacred Literature, ed. R.E. Friedman, Near Eastern Studies 22 (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1981), pp. 35–54.

See Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel, p. 117; and Yohanan Aharoni, The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1967), pp. 269–273.

See also G.W. Ahlström, Royal Administration and National Religion in Ancient Palestine (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1982), pp. 25, 47–74.

The reference to the bamot of Baal in the Transjordanian Balaam story (Numbers 22:41) comes rom the Elohist’s text (eighth-seventh centuries B.C.E.; see Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? p. 253), although the story originally may derive from earlier epic material (see Jo Ann Hackett, “Religious Traditions in Israelite Transjordan,” in Miller, Hanson and McBride, eds. Ancient Israelite Religion, p. 128). From this perspective, the mention of a bamah (or bt bmt) in the Mesha Inscription is interesting. This Transjordanian text describes the mid-ninth-century B.C.E. victory of Mesha, king of Moab, over Israel. It mentions that Mesha’s father built a bamah for Kemosh in Qarhoh, and that following its destruction, Mesha restored it (Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 2nd edition, ed. James B. Pritchard [Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1955], pp. 320–321; Mitchell Dahood, “The Moabite Stone and Northwest Semitic Philology,” in The Archaeology of Jordan and Other Studies, ed. Lawrence T. Geraty and Larry G. Herr [Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews Univ. Press, 1986], p. 437). Biran has noted the close (although not necessarily amicable) relationship between Moab and Israel during these centuries (see “To the God Who Is in Dan,” p. 143), and this relationship may well extend to shared modes of worship.

Judges 17–18 describes the migration of the tribe of Dan to Laish (Tel Dan). The Danites conquered Laish, renamed it Dan and set up an idol they had commandeered from a man in Ephraim named Micah. Micah’s priest, a Levite from Bethlehem and a member of the clan of Judah, joined the Danites in their new northern home. The Levitically run shrine established at Dan remained in existence “as long as the House of God was at Shiloh” (Judges 18:31). Thus, Dan was not a blank slate onto which the Israelite monarchy could impose its wishes. Jeroboam had to contend with the preexisting Levitical cult at Dan. For the Israelite monarchy, ruling from Shechem far to the south and isolated from Dan by the mountain chains of the Galilee, control of Dan was crucial. It was to Jeroboam’s advantage to utilize the already existing clergy, involving them—and their congregants—in the national cult that served to link them to the Israelite monarchy. The bamah at Dan has recently been excavated.

The story of Abimelech ben Jerubaal (Judges 9) takes place in 12th-century Shechem, a city that remained under Canaanite control. The Temple of Baal-berith/El-berith (Judges 9:4, 27, 46–49), which Abimelech and his supporters destroyed, has been identified with the Canaanite Fortress Temple 2b of Temenos 9, well known from excavations at Shechem. See Lawrence E. Toombs and G. Ernest Wright, “The Fourth Campaign at Balatah (Shechem),” BASOR 169 (1963), p. 29; Toombs, “Shechem: Problems of the Early Israelite Era,” in Symposia Celebrating the Seventy-fifth Anniversary of the Founding of the American Schools of Oriental Research (1900–1975), ed. F.M. Cross (Cambridge, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1979), p. 73. The scale of this Canaanite sanctuary stands in contrast to contemporaneous Israelite places of worship, which were, by comparison, quite small.

Amihai Mazar, “The ‘Bull Site’: An Iron Age I Open Cult Place,” BASOR 247 (1982); pp. 27–42; Mazar, “Bronze Bull Found in Israelite ‘High Place’ from the Time of the Judges,” BAR 09:05.

Adam Zertal, “An Early Iron Age Cultic Site on Mt. Ebal: Excavation Seasons 1982–1987,” Tel Aviv 13–14 (1986–1987), pp. 105–165; Zertal, “Has Joshua’s Altar Been Found on Mt. Ebal?” BAR 11:01.

Israel Finkelstein, The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988), pp. 226–232.

Yigael Yadin, Hazor: The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy, 1970 (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1972), pp. 132–134; Pirhiya Beck, “The Metal Figures,” in Hazor III–IV: An Account of the Third and Fourth Seasons of Excavation, 1957–1958, Text, ed. A. Ben-Tor (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1989), p. 361.

Yadin, Hazor: The Rediscovery of a Great Citadel of the Bible (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1975), p. 257.

David Ussishkin, “Shumacher’s Shrine in Building 338 at Megiddo,” Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ) 39 (1989), pp. 149–172. For a rebuttal of Ussishkin’s position, see Ephraim Stern, “Shumacher’s Shrine in Building 338 at Megiddo: A Rejoinder,” IEJ 40 (1990), pp. 102–107.

Paul W. Lapp, “The 1963 Excavation at Ta’annek,” BASOR 173 (1964), pp. 26–39; Lapp, “The 1968 Excavations at Tell Ta’annek,” BASOR 195 (1968), pp. 42–44; and Walter Rast, Taanach I: Studies in the Iron Age Pottery (Cambridge, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1978), pp. 26–39.

Yohanan Aharoni, Investigations at Lachish: The Sanctuary and the Residency, Lachish V (Tel Aviv: Gateway, 1975), pp. 26–32.

Amihai Mazar, Excavations at Tel Qasile, Part 1, The Philistine Sanctuary: Architecture and Cult Objects, Qedem 12 (1980), pp. 47–53.

Frances James, The Iron Age at Beth Shan: A Study of Levels VI–IV (Philadelphia, PA: The University Museum, 1966), pp. 110–118; Magnus Ottosson, Temples and Cult Places in Palestine (Boreas, Sweden: Uppsala Studies in Ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern Civilizations; Uppsala, Sweden: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 1980), pp. 71–73.

Khair N. Yassine, “The Open Court Sanctuary of the Iron Age I Tell el-Mazar, Mound A,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly (PEQ) 118 (1984), pp. 108–118.

Shalom Levy and Gershon Edelstein, “Cinq années de fouilles à Tel ‘Amal (Nir David),” Revue biblique 79 (1972), pp. 331–334.

According to Shulamit Geva, the eighth-century city of Hazor “was characterized by the absence of worship (no material remains of such, and no places of worship) and also apparently the absence of faith (as corroborated by the prophets).” Among those living at Hazor, religious practice was most likely affected by pilgrimage to the royal sanctuary at Dan (Hazor, Israel: An Urban Community of the 8th Century B.C.E., BAR International Series 543 [Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1989], pp. 108–110).

See Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible (New York: Doubleday, 1990), p. 143; Lawrence E. Stager and Samuel R. Wolff, “Production and Commerce in Temple Courtyards: An Olive Press in the Sacred Precinct at Tel Dan,” BASOR 243 (1981), p. 99. Others think that the podium was a raised platform on which sacrifices were made. See John S. Holladay, Jr., “Religion in Israel and Judah Under the Monarchy: An Explicitly Archaeological Approach,” in Miller, Hanson, McBride, eds., Ancient Israelite Religion, p. 255 and references there.

Stager and Wolff, “Production and Commerce in Temple Courtyards,” pp. 95–97. Biran, on the other hand, suggested that the installation was used for special water libations (“Two Discoveries at Tel Dan,” IEJ 30 (1980), pp. 91–95; see also “Is The Cultic Installation at Dan Really an Olive Press?” BAR 10:06.)

Ephraim Stern and Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, “Excavations at Tel Kedesh (Tell Abu Qudeis),” in Excavations and Studies: Essays in Honour of Professor Shemuel Yeivin, ed. Y. Aharoni (Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, 1973), pp. xiv, 96; Stern and Beit-Arieh, “Excavations at Tel Kedesh (Tell Abu Qudeis),” Tel Aviv 6 (1979), pp. 5–6.

James B. Pritchard, Tell es-Sa‘idiyeh: Excavations on the Tell, 1964–1966, University Museum Monograph 60 (Philadelphia: The University Museum, 1985), pp. 8–9, 77–80.

Y. Aharoni, “Arad: Its Inscriptions and Temple,” p. 19; see also Ze’ev Herzog, Miriam Aharoni and Anson F. Rainey, “Arad—An Ancient Israelite Fortress with a Temple to Yahweh,” BAR 13:02. Noting the dissimilarity in size between the two standing stones within the Holy of Holies and the matching dissimilarity between the pillars flanking its entrance, A. Mazar suggested that the large and small stones reflected Yahweh and Asherah respectively (Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, p. 497).

Letter 18 from the Elyashib archive, which mentions byt yhwh (the house/temple of Yahweh), refers to the sanctuary at Arad rather than the Jerusalem Temple. See David Ussishkin, “The Date of the Judaean Shrine at Arad,” IEJ 38/3 (1988), p. 155.

See Z. Herzog, M. Aharoni, A.F. Rainey and Shmuel Moshkovitz, “The Israelite Fortress at Arad,” BASOR 254 (1984), p. 4, and references therein.

See Ussishkin, “The Date of the Judaean Shrine at Arad,” pp. 151–154, and references therein, esp. n. 45.

Y. Aharoni, “Excavations at Tel Beer-sheba: Preliminary Report of the Fifth and Sixth Seasons, 1973–1974,” Tel Aviv 2 (1975), pp. 154–156. One suggestion places the sanctuary on the spot of the later Building 32 (p. 162); see also Herzog, Rainey and Moshkovitz, “The Stratigraphy at Beer-sheba and the Location of the Sanctuary,” BASOR 225 (1977), pp. 56–58. A second claims that it was located southwest of the city gate and associated with Building 430. See Yadin, “Beer-sheba: The High Place,” p. 8.

Also see the following BAR articles: “Horned Altar for Animal Sacrifice Unearthed at Beer-Sheva,” BAR 01:01; and Hershel Shanks, “Yigael Yadin Finds a Bama at Beer-Sheva,” BAR 03:01.

Y. Aharoni, “Tel Beersheba,” Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, 4 vols., ed. Michael Avi-Yonah (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1975), vol. 1, p. 126.

Ze’ev Meshel, Kuntillet ‘Ajrud: A Religious Centre from the Time of the Judaean Monarchy on the Border of Sinai, Israel Museum Catalogue 175 (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1978).