044

For many centuries the Protoevangelium of James was an enormously popular and influential apocryphal gospel. Written in the latter half of the second century, purportedly by Jesus’ brother James, it tells the story of the birth of Mary and, later, of Jesus. It is charming and moving and in the best gospel tradition.

In this infancy narrative, Mary is the daughter of a wealthy, but long-childless couple, Joachim and Anna, who vow to give their unborn child to the Temple in gratitude. (The story appears to be patterned after the story of Elkanah and Hannah and their son Samuel in 1 Samuel 1–2.) From the age of three, Mary lives as a ward of the Temple (like Samuel). In the Temple she is fed by an angel. When she is grown, the high priest Zacharias is called upon to find a husband for her by assembling elderly widowers and having them draw lots. One of them is Joseph. Each of the widowers is given a rod. A dove comes out of Joseph’s rod and flies onto his head—a sign from God that he is the man. At first Joseph refuses, fearful that he will be a laughing-stock when she does not conceive. It will be seen as his fault: He is an old man and she is a young virgin. He needn’t have been worried, however. She becomes pregnant without Joseph’s intervention.

When Joseph comes home one day and finds her six months pregnant, he accuses her of infidelity. She weeps bitterly, proclaiming her innocence.

Not long thereafter, the emperor Augustus orders a census in Bethlehem. In this version of the story, it is Mary, not Joseph (as in Matthew and Luke), who is a descendant of David, so the couple takes off for Bethlehem with the expectant mother riding on a donkey.

When they get to within 3 miles of Bethlehem, Mary feels labor pains and asks Joseph to take her down from the donkey. There she apparently sat down on a rock—and this is the whole point of this article—while Joseph found a cave where she could have some privacy. Joseph then went off to search for a midwife. Mary, however, could not wait and gave birth to Jesus in the cave.

At that moment “a great light shone in the cave so that the eyes could not bear it. And in a little while that light gradually decreased, until the infant appeared.”

046

At that same moment, other miracles occurred. Joseph describes them:

I … saw … the birds of the air keeping still … And those who were eating did not eat … and those that were conveying anything to their mouths did not convey it; but the faces of all were looking upwards. And I saw the sheep walking, and the sheep stood still; and the shepherd raised his hand to strike them, and his hand remained up.

In about 456, according to Cyril of Scythopolis, a church was built to mark the spot where Mary dismounted and sat down outside of Bethlehem. It is called the Kathisma, “seat” or “chair” in Greek.

For a thousand years the church was lost. All that was known was that it was south of Jerusalem, about 3 miles from Bethlehem, according to ancient reports. And then, as so often happens in Israel, it was found by accident.

In 1993 a path that led to the road from Jerusalem to Bethlehem near the Monastery of Mar Elias was being paved. The path ran through an olive grove belonging to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchy. It was not long before the workers hit ancient remains, and the work was promptly stopped. A rescue dig, led by Rina Avner, was organized by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA). In 1999 the University of Athens and the Greek Orthodox Patriarchy joined the sponsorship of the dig. In the end, it extended over three seasons, the last one in 2000. And now Dr. Rina Avner has written her doctoral dissertation at the University of Haifa on her excavation of the Kathisma.

What she found was the church built to mark the spot where the Virgin Mary stopped—and sat—just before giving birth to her son.

Well, it’s not exactly a church. It’s first and foremost a martyrium, a special structure that also functions as a church (or mosque) to mark the place of a holy event. A standard church at this time would have been a basilica—a narrow narthex across the front, a long central nave with columns on either side creating side aisles, and an apse at the end (or sometimes a triple apse). A martyrium, more often than not, is octagonal in plan. The best-known example is the octagonal structure that marks the site of St. Peter’s house, where Jesus stayed in Capernaum (Matthew 8:14//Mark 1:29//Luke 4:38).a

047

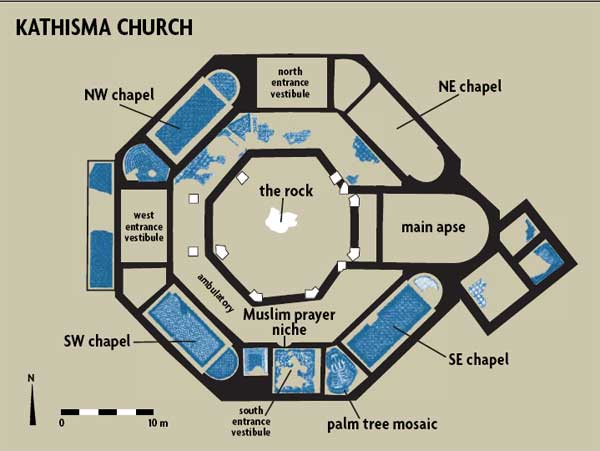

The Kathisma church is also an octagon. Indeed, like the martyrium at St. Peter’s house, the Kathisma church is three concentric octagons. In the center a rock protrudes above ground, apparently where Mary sat when she descended, with Joseph’s help, from the donkey.

Surrounding the innermost octagon is an ambulatory. At the eastern end of this ambulatory is a large apse, thus incorporating the focus of a church into the structure.

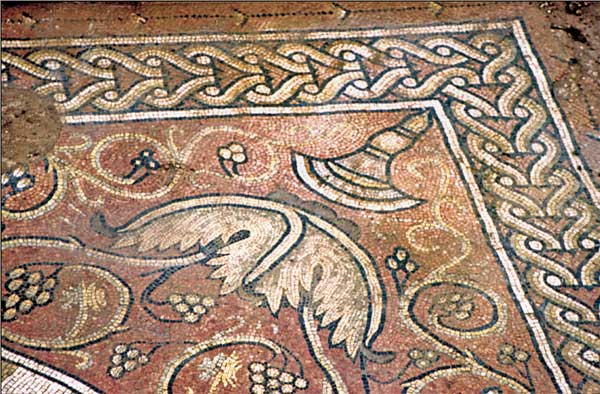

Between the two outer octagons, which the excavator calls the “Large Octagon,” is not a walkway, but two different kinds of rooms. On the north, south and west are rectangular rooms that served as anterooms to the imposing long rooms on the diagonals. These four rooms on the diagonals were in fact chapels, dedicated to Mary Theotokos (“Mary who gave birth to God” or simply “Mary Mother of God”). Each chapel consisted of a long rectangular hall with an apse at the end. Each of these chapels was paved with a geometric mosaic carpet.

With this elaborate structure, it will come as no surprise that the Kathisma Church was a very large building covering about 2.5 acres. From east to west it measured just short of 135 feet. Its size and the four chapels reflect the fact that it must have been the destination of throngs of pilgrims.

The structure had three phases, dated primarily by coins and by references in ancient texts. The initial construction occurred in the mid-5th century. Already by that time, a holy day was being observed at the site in mid-August (the exact date changed from time to time) dedicated to Mary Mother of God. This was apparently the earliest holiday dedicated to Mary, even earlier than the holiday observed at the site in Jerusalem from which tradition (and a church) holds that she was assumed, body and soul, into heaven after her death. All we 048know about the Kathisma observance is that it involved a candle-lit procession. According to Avner, the Kathisma was the first of several churches built to express solidarity with the ecumenical councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451), which officially recognized and confirmed Mary’s status as Theotokos (“Mother of God”). The decisions of the councils provided strong support to the cult of the Theotokos, whose members had already been worshiping not only at the Kathisma but elsewhere throughout the Holy Land.

In the early to mid-sixth century, the Kathisma church was remodeled somewhat but not in any major way. From both the first and the second phases, the excavators found mosaics. Perhaps the most intriguing change in the second phase, however, was the introduction of some kind of lustration ceremony. From this period the excavators found the remnant of a clay pipe that led a stream of water to the center of the stone in the center of the martyrium, at the precise spot where, supposedly, Mary sat. A little cup was carved out of the stone for the water. What rite of ablution was involved is unknown. Perhaps the water that touched the stone became especially holy and was taken home by pilgrims. An anonymous sixth-century pilgrim known only as the Piacenza Pilgrim saw especially 049sweet water apparently emerging from the stone and being taken away:

I saw standing water which came from a rock, of which you can take as much as you like up to seven pints. Every one has his fill, and the water does not become less or more. It is indescribably sweet to drink, and people say that Saint Mary became thirsty on the flight into Egypt and that when she stopped here the water immediately flowed. Nowadays there is also a church building there.1

In the third and final phase, which occurred after the Arab conquest in the seventh century, the structure was transformed into a mosque—or at least a part of it was. Muslim attitudes—and actions—with regard to churches (and synagogues) after the Arab conquest varied widely. Sometimes the Muslims destroyed them. Sometimes they allowed them to continue to be used and even to be built and rebuilt. It depended on the particular ruler, who lived in the town (Muslims or Christians), whether the town surrendered to Arab forces peaceably or was conquered by force, and other factors. Treaties (covenants) with conquered towns supposedly governed what Christians could do. Sometimes they were observed, sometimes not. In two recorded instances, Muslims seized only 050a quarter of a church. In another case, a caliph destroyed all the churches in the town but one, and demanded a price of 3,000 dinars for sparing it. The Christians were able to raise only 2,000 dinars, so the caliph ceded only two-thirds of the church and turned the other third into a mosque.

One historian of the period noted, “It was not unknown that Muslims and Christians met on peaceful terms in a church.”2 That may well have been the case in the Kathisma, for the Muslims, too, revered Mary.

There the Muslims created a mosque in the middle of the southern side of the ambulatory. A prayer niche on the south side of this area (facing Mecca) easily identifies it as a mosque. The Muslims also added several rooms on the eastern side of the building, outside the apse of the church that leads off the center of the building.

The finest mosaics in the structure are from the Arab period. Arab-period mosaics in the church feature cornucopias inlaid with jewels and pearls that recall the mosaics in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The most elaborate mosaic in the Kathisma Church is in the additional rooms east of the original church. In addition to the many colored stones (green, yellow, red and black), some tesserae are round and white to imitate pearls.

What is unclear is whether the Muslims ousted the Christians from the church completely or only claimed part of the building.

051

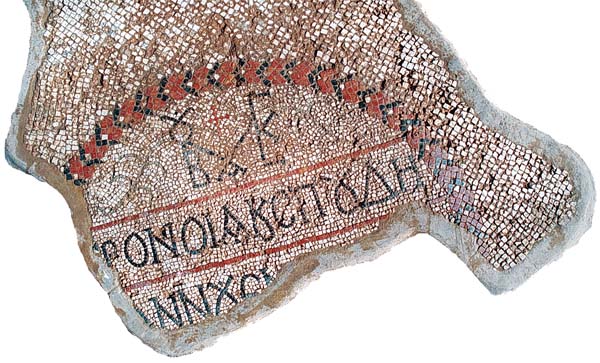

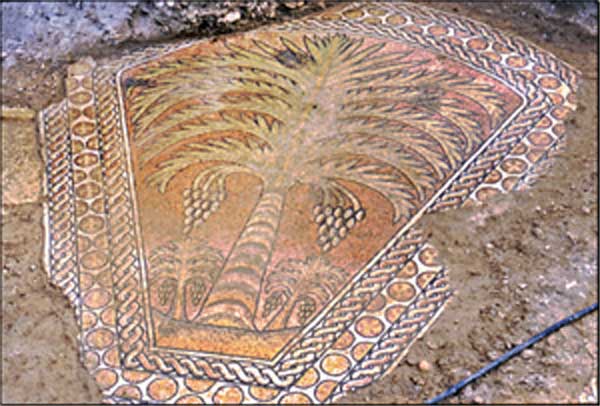

A short Christian inscription from the Arab period (eighth–ninth centuries) reflects the fact that even as late as this, Christians were still making pilgrimage visits to the site. According to Leah di Segni, Israel’s leading expert in Greek inscriptions, the mosaic inscription reads: “Of Basilius. By the provision and effort of John the recluse [?] …” It was evidently through John’s enterprise that the mosaic was made, and Basilius is honoring him for this.3 John is identified as a recluse. Basilius was apparently so well-known that he needed no identification; di Segni thinks he may have been a ninth-century patriarch of Jerusalem. John the recluse was probably a monk at the large monastery adjacent to the church. And, as di Segni points out, recluses are known to have played active roles in church leadership in this period. How long Christians continued to pray here we do not know. However, Muslims, too, honor Mary, and the Qur’an refers to Mary’s labor pains while she sat beneath a palm tree. So perhaps in the Arab period, the structure was shared by Christians and Muslims.

Just off the southeastern corner of the mosque area is a lovely mosaic of an elaborate palm tree. One is left to wonder whether this Muslim mosaic is in remembrance of Mary’s labor pains as she sat beneath a palm tree.

For many centuries the Protoevangelium of James was an enormously popular and influential apocryphal gospel. Written in the latter half of the second century, purportedly by Jesus’ brother James, it tells the story of the birth of Mary and, later, of Jesus. It is charming and moving and in the best gospel tradition. In this infancy narrative, Mary is the daughter of a wealthy, but long-childless couple, Joachim and Anna, who vow to give their unborn child to the Temple in gratitude. (The story appears to be patterned after the story of Elkanah and Hannah and their son Samuel […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

James F. Strange and Hershel Shanks, “Has the House Where Jesus Stayed in Capernaum Been Found?” BAR 08:06.

Endnotes

John Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims Before the Crusades (Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips, 1977), p. 85

A.S. Tritton, The Caliphs and Their Non-Muslim Subjects, (London: Frank Cass, 1970), p. 45. The account in the previous paragraph is based on Chapter III of this book.