The answer seems obvious: a man named Luke, of course. But do we really know this, and, if so, how? The gospel itself never reveals the author’s name. The title “The Gospel According to Luke”—printed in virtually every Christian Bible today—is late: We have no evidence that it appeared on the earliest versions of the gospel.

Over the centuries, numerous traditions have evolved around this somewhat shadowy evangelist: Luke is credited with writing not only his gospel but the New Testament Book of Acts as well. He was, according to tradition, a physician and a friend of Paul’s, and he is described as a gentile writing for a gentile audience. The textual evidence suggests that these stories are very early, dating to the first and second century. By the fourth century, these traditions were well enough established to be summarized by the historian Eusebius and the church father Jerome (see the second sidebar to this article). Still later, Luke was depicted as a portrait painter whose most famous subject was the Virgin Mary herself. These traditions—with further embellishments—continued throughout the Middle Ages.

But how have these traditions withstood both the test of time and the critical eye of modern biblical scholarship? In the opening lines of his gospel, Luke offers his own explanation of why he began to write:

Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed on to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, I too decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the truth concerning the things about which you have been instructed.

Luke 1:1–4

The “events” to be described are, of course, the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. Note that the gospel writer does not count himself among the eyewitnesses to Jesus’ life. And he describes himself as only one of many who have set out to write Jesus’ story. The author dedicates his text to Theophilus, who is not mentioned again in Luke’s gospel.

Theophilus’s name does appear once more in the New Testament, however—in the introduction to the Book of Acts. This is our first clue regarding an assertion that is commonly made about the author of the Third Gospel: He is also responsible for writing Acts.

The Book of Acts begins:

In the former treatise, Theophilus, I wrote about all that Jesus did and taught from the beginning until the day when he was taken up to heaven, after giving instructions through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen.

Acts 1:1–2

The Book of Acts is thus presented as the Third Gospel’s sequel. In it, Luke will continue to relate the events that transpired among the earliest Christians, from shortly after Jesus’ death until just before Paul’s.

The extrabiblical evidence that these two books are by the same hand dates as early as the last third of the second century, when both the Muratorian Canona (the earliest known list of writings deemed canonical by the church) and the early church father Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons, identify Luke as the author of both the Third Gospel and the Book of Acts.1

Of all the assertions traditionally made about Luke, this one has fared the best in modern scholarship. Today, however, the attribution of Luke and Acts to a single author is based primarily on shared literary and thematic elements.2 For example, both texts include travel narratives in which the hero—Jesus or Paul—journeys to Jerusalem and is arrested on false charges (Luke 9:51–19:28; Acts 19:21–21:36). The miracles performed by Peter and Paul in Acts mirror those of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. All three figures heal lame men with the instructions: “Stand up and walk” (Acts 3:1–10, 14:8–11; Luke 5:17–26); and all three resurrect the dead, with Peter and Jesus employing the same command: “Get up” (Acts 9:36–40, 20:7–12; Luke 8:40–56).

In Luke, the Holy Spirit descends upon Jesus while he is at prayer before 40 days of “testing” and before he begins his public ministry (Luke 3:21–22). So it is in Acts, when the Holy Spirit falls upon his disciples on the Feast of Pentecost while they are at prayer after 40 days of instruction but before they begin their public ministry (Acts 2:1–4). Furthermore, the account of the first Christian martyr, Stephen, who is tried before the high priest and then stoned to death (Acts 6:8–15, 7:54–60), reflects the trial and death of Jesus (Luke 22–23). Jesus, at his trial, predicts that “the Son of Man will be seated at the right hand of the power of God” (Luke 22:69); Stephen, standing before the high priest, exclaims that he “[sees] the heavens opened and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God” (Acts 7:56). When Jesus dies, he cries out: “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit” (Luke 23:46); Stephen makes a similar plea during his martyrdom: “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit” (Acts 7:59).

Luke and Acts share an overarching geographical plan that has Jerusalem at its center. In Luke, events move toward Jerusalem, with the gospel beginning and ending in the Temple. In Acts, Paul and others alternately journey outwards from Jerusalem (to Judea and Samaria, Asia Minor, Europe and ultimately Rome) and back again (see Acts 12:25, 15:2, 18:22, 19:21, 20:16, 21:13, 25:1). Both books also see salvation history as falling into three periods: the period of Israel, the period of Jesus and the period of the church. Both books demonstrate an interest in the same themes: Christology, the Holy Spirit, eschatology and discipleship. Finally, both employ the same vocabulary and exhibit a strikingly similar writing style.3 Together, these features have led to a widespread consensus among scholars regarding the common authorship of Luke and Acts, underscored by the widespread use of the phrase “Luke-Acts” ever since it was coined by the American Bible scholar Henry Cadbury in 1927.

The separation of Luke from Acts in the canon of scripture is usually explained by the limitations of the scroll, the presumed medium of communication in the first-century Mediterranean world. Luke and Acts were simply too long to fit on one scroll, this theory goes, and thus were divided prior to “publication.” Or, some scholars have suggested, the two treatises may have been separated when they were taken into the canon, with Luke being subsumed under the rubric of the “four-fold gospel” and Acts serving as a bridge between the gospel collection and the letters. (John’s gospel now separates Luke and Acts.)

Now that we have identified the original text as Luke-Acts, long since divided into two books, the next question is, of course, who wrote it?

The gospel title—“Euangelion kata Lukan,” (The Gospel According to Luke)—appears at the end of the oldest extant manuscript of the Gospel of Luke, a papyrus known as P75, now in the Bodmer Library in Geneva. But this fragmentary manuscript dates only to about 175 to 225, or 100 to 125 years after the gospel is thought to have been written. The title probably reflects the oldest tradition, linking an author named Luke to the writing of the Third Gospel. The reliability of this tradition, however, is uncertain.

What else do we know about the author?

As we have seen, in the prologue to the gospel the author seems to identify himself as a second-generation Christian relying on others’ eyewitness testimony. He cannot therefore be counted among the apostles. Furthermore, throughout the Book of Acts, when describing Paul’s activities the narrator occasionally shifts from the third- to the first-person plural “we” (Acts 16:10–17, 20:5–15, 21:1–18, 27:1–28:16). For example, of Paul’s final trip to Jerusalem, he writes: “When we found a ship bound for Phoenicia, we went on board and set sail. We came in sight of Cyprus; and leaving it on our left, we sailed to Syria and landed at Tyre, because the ship was to unload its cargo there. We looked up the disciples and stayed there for seven days. Through the Spirit they told Paul not to go into Jerusalem” (Acts 21:2–4).

The church father Irenaeus was one of the first to interpret these “we” passages as evidence that Luke was a companion of Paul: “But that this Luke was inseparable from Paul and was his fellow-worker in the gospel he himself makes clear, not boasting of it, but compelled to do so by truth itself.”4

Modern scholars, however, are deeply divided regarding the significance of the “we” passages: Some argue that the first-person narration derives from diary material and demonstrates participation by the gospel writer (or at least by the author of the diary material). Others argue that the author or a later editor is responsible for creating the first-person narration and that the “we” passages may not be used as evidence that the author was an inseparable or even sometime companion of Paul. In fact, based on apparent tensions between the Lukan Paul and the Paul of the Epistles, some have questioned whether the author of Acts knew Paul at all, much less was his traveling companion.5 For example, Luke and Paul give conflicting accounts regarding the number and nature of Paul’s visits to Jerusalem, and (except in Acts 20:28) the Lukan Paul never refers to the death of Jesus as a saving event—a central point in the letters of Paul (1 Corinthians 15:3; 2 Corinthians 5:21; Romans 3:25, etc.). Still other scholars have argued that first-person narration was simply a common literary device in ancient sea-voyage literature and thus may not be used as evidence that the author was an eyewitness to the events narrated. None of these views has won a clear majority of support.

The Book of Acts is not the only potential source of information about the relation between Paul and Luke, however. The name Luke appears three times in letters attributed to Paul. (These are, incidentally, the only appearances of this name in the New Testament.) Unfortunately, this Luke is never identified as the gospel writer. Of course, that hasn’t stopped speculation, from the time of Irenaeus on.

In a letter to Philemon, a Christian living in Colossae in Asia Minor, Paul lists a man named Luke as one of his “fellow workers” (Philemon 24); and in an open letter to the Christian community of Colossae, Paul sends greetings from “Luke, the beloved physician” (Colossians 4:14). Finally, the author of the Pastoral Epistles, most likely one of Paul’s followers who writes in Paul’s voice, inserts these words in 2 Timothy: “Do your best to come to me soon, for Demas, in love with this present world, has deserted me and gone to Thessalonica; Crescens has gone to Galatia, Titus to Dalmatia. Only Luke is with me [emphasis added]. Get Mark and bring him with you, for he is useful in my ministry (2 Timothy 4:9–11).” These scant references have augmented—or simply reflect—Luke’s reputation as one of Paul’s most faithful companions.

They also lead us to the next assertion traditionally made about Luke: He was a physician, as is suggested by Colossians 4:14. This, too, is repeated in the writings of Irenaeus and in the Muratorian Canon but has received mixed reviews in recent scholarship. Late in the 19th century, Irish physician and scholar William K. Hobart searched the healing stories in Luke for what he believed were medical terms, such as “crippled,” “pregnant” or “abscess,” or ordinary words used in a “medical” sense. From this “internal evidence” Hobart concluded that Luke and Acts were written by the same person, and that the writer was a medical man.6 But Henry Cadbury soon dismantled this argument by demonstrating that the terms on Hobart’s lists occur in the Septuagint, Josephus, Plutarch and Lucian, all non-medical writers. Cadbury concluded, “The style of Luke bears no more evidence of medical training and interest than does the language of other writers who were not physicians.”7 In a tongue-in-cheek lexical note entitled “Luke and the Horse-Doctors,” Cadbury later showed that Luke’s vocabulary shows a remarkable similarity with the corpus of writings of ancient veterinarians!8 His refutation was so effective that he virtually eliminated this special pleading to a so-called medical vocabulary.9 His students used to jest that Cadbury earned his doctorate by taking Luke’s away.

This century has also witnessed a sharp attack on the traditional identification of Luke as a gentile writing for a gentile audience. This long-dominant view may have roots that reach back as far as the second century to an extrabiblical text, Prologue to the Gospels. This text, also known as the “Anti-Marcionite” Prologue, contained a description of Luke that church father Eusebius, among others, followed: “Luke was a Syrian of Antioch, by profession a physician, the disciple of the apostles, and later a follower of Paul.”10 In Luke’s day, Antioch was a prominent early Christian center. According to Acts 11:26, “It was in Antioch that the disciples were first called ‘Christians.’” All of Paul’s missionary journeys departed from and returned to this city.

The view that Luke was a gentile does not rest solely on the tradition that he was an Antiochene, however. Rather, some accept Colossians 4:14 as identifying Luke as a gentile. In the preceding verses of this letter, Paul lists a number of Jews who work with him: “Aristarchus my fellow prisoner greets you, as does Mark the cousin of Barnabas, concerning whom you have received instructions—if he comes to you, welcome him. And Jesus who is called Justus greets you. These are the only ones of the circumcision among my co-workers for the kingdom of God, and they have been a comfort to me [emphasis added]” (Colossians 4:10–11). Paul then goes on to list a handful of other workers who, many readers presume, must not be Jews, but “Greeks.” He includes “Luke, the beloved physician” in this latter list (Colossians 4:14).

Connected to the view that Luke was not Jewish is the widely held assumption that Luke’s gospel is the “gentile gospel,” written for a predominantly, if not exclusively, gentile audience. It includes Simeon’s prophecy over the infant Jesus that he would be a “light for revelation to the gentiles” (Luke 2:32), the healing of the gentile centurion’s slave (Luke 7:1–10) and the commission by the risen Christ to the disciples to preach “forgiveness of sins to all nations” (Luke 24:47),b all of which foreshadow the interest in the gentile mission that occupies much of Acts.

Recently, however, a small but vocal minority has raised the possibility that Luke was in fact Jewish, or at least deeply interested in Judaism. (They assume that the Luke referred to in Colossians was either a “God-fearer” with deep Jewish interests or not the same person as the author of the Gospel.) This view too has ancient roots. In the fourth century, Bishop Epiphanius of Cyprus suggested that Luke was one of the 70 disciples sent out by Jesus (Luke 10) and was thus presumably Jewish.11

Some have assumed that if Luke were from such a well-known Greco-Roman city as Antioch, he must have been a gentile. The first-century C.E. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus gives evidence that a Jew from Antioch could have been called an “Antiochene.” Thus, even the tradition that Luke was from Antioch, an “Antiochene,” does not preclude his being Jewish.12

Antioch did have a Jewish community: Josephus notes that the first Seleucid king, Seleucus Nicator (c. 358–281 B.C.E.), who made Antioch his capital, granted the local Jews citizenship in gratitude for their having fought with the Greek armies.13 And according to John Chrysostom, who served as deacon of Antioch in the late fourth century C.E., the city had several synagogues. The archaeological evidence of the Jewish community is limited, however, to a small stone fragment of a menorah and a lead curse tablet referring to the biblical God Yahweh.c

The narrative of Acts can also be read as supporting the view that Luke was a Jew or at least deeply interested in Judaism. Acts clearly presents the “Christian” movement as one Jewish sect among several. This perspective is shared by Christian, Jewish and Roman characters in Acts, as well as the narrator himself: Twice, the Christian Paul in Acts makes the claim, “I am a Jew” (Acts 21:39, 22:3). Later in Acts, he states that he has “belonged to the strictest sect of our religion and lived as a Pharisee” (Acts 26:5, see also Acts 24:14). Tertullus, the Jewish advocate for the high priest before Felix, states: “We have, in fact, found this man a pestilent fellow, an agitator among all the Jews throughout the world, and a ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes” (Acts 24:5). Further, the Jews in Rome say to Paul: “But we would like to hear from you what you think, for with regard to this sect we know that everywhere it is spoken against” (Acts 28:22). The Roman procurator Festus reports to King Agrippa about Paul: “His [Jewish] accusers…brought no charge in his case of such evils as I supposed, but they had certain points of dispute with him about their own superstition” (Acts 25:18–19).14 Finally, the gospel narrator states: “But some believers [in Jesus] who belonged to the sect of the Pharisees stood up and said, ‘It is necessary for them to be circumcised and ordered to keep the law of Moses’” (Acts 15:5). Such evidence has led Lukan scholars like David Tiede to conclude that “the polemics, scriptural arguments, and ‘proofs’ which are rehearsed in Luke-Acts are part of an intra-family struggle [among Jews] that, in the wake of the destruction of the temple, is deteriorating into a fight over who is really the faithful ‘Israel.’”15

The idea that Luke was writing to a predominantly gentile community has also been challenged by those who argue that any quest for the “Lukan community” is ultimately a futile one. In fact, recently the argument has been rather forcefully made that all four canonical gospels were aimed at the general Christian audience living throughout the Mediterranean world in the second half of the first century and not to specific communities.16 Arguments about authors and audiences are further complicated by an emerging awareness of how difficult it is to draw firm lines between the “symbolic” world evoked by the narrative and the “real” world of the author.

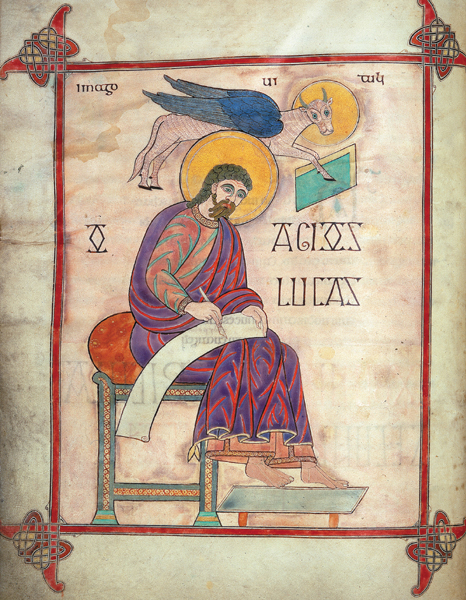

The final assertion traditionally made about Luke—namely, that the gospel writer was also an artist—is probably the least familiar to readers and unfortunately, the most difficult to trace. Countless Byzantine images of the Madonna and Child have been attributed to Luke, including an icon dated to the sixth to seventh century in Rome’s Santa Maria Maggiore; an icon, dating to about 1300, in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome; and the famous Black Madonna of Czestochowa, Poland. The earliest textual evidence is a sixth-century story attributed to Theodorus Lector, who wrote: “Eudocia [wife of the early fifth-century Byzantine emperor Theodosius] sent to Pulcheria [her sister-in-law] from Jerusalem an image of the Mother of God painted by the apostle Luke.”17

During the Renaissance, the image of Luke painting the Virgin became a popular subject among artists living in the regions north and south of the Swiss Alps. One of the earliest examples, St. Luke Portraying the Virgin (c. 1453), by the Flemish artist Rogier van der Weyden, offers an intimate portrait of Luke and the Virgin and Child in a contemporaneous Flemish household.

At some point in the late Middle Ages, Luke became the patron saint of artists and their guild. In 1577, one of the first academies devoted to the training of artists in Rome was named in honor of Saint Luke—Accademia di San Luca. Florentine painters belonged to the guild of doctors and pharmacists not only because they had to grind minerals, herbs and earth for their pigments, just as pharmacists did for their medicines, but also because painters and doctors enjoyed the protection of the same patron saint, Saint Luke, physician and painter.18

Rogier van der Weyden’s painting, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, was probably created for the guild of Saint Luke in Brussels and was intended to hang above an altar maintained by artists in a local church.19 Van der Weyden (and many other artists) further established his connection with the evangelist by using his own face for the portrait of Luke. The Italian painter, architect and biographer of artists Giorgio Vasari did the same when, in about 1565, he painted a fresco of Luke painting the Virgin for the artists’ chapel (the Cappella di S. Luca) in the Florentine church of Santissima Annunziata.

The origins of the legend about Luke the painter are not at all clear, however. One fascinating theory suggests that the image of the reading philosopher in the classical period became in the Augustan period that of a writer, which, in the early Christian period, served as a model for the writing evangelist. Later, a painting board was substituted for the codex, transforming the figure into the painter Saint Luke.20 What this view fails to account for is why it is Luke, and none of the other evangelists, around whom this legend grew.

Two possibilities commend themselves: First, note that all the paintings attributed to Luke are paintings of Mary. Augustine had commented that no one knew what the Virgin looked like,21 but at some point the need must have risen for a vera ikon (true image) of the Madonna. Logically, the image had to have been painted by someone who lived in Mary’s time. Who better than Luke, who writes more about Mary and the infancy of Christ than all the other canonical Gospel writers combined?

Luke’s long-recognized literary artistry may also have contributed to his identification as a painter. The early church scholar Jerome (c. 347–420) asserts that Luke’s “language in the Gospel, as well as in the Acts of the Apostles, that is, in both volumes is more elegant, and smacks of secular eloquence.”22 This view of Luke’s literary prowess continued through the medieval and Renaissance periods. In the 13th century, the writer Jacobus de Voragine (1229–1298) praised Luke’s writing as clear, pleasing and touching: “His gospel is permeated by much truth, filled with much usefulness adorned with much charm, and confirmed by many authorities.”23

In ancient rhetorical traditions, clarity was often linked to vividness (appealing to the eye and not the ear).24 Perhaps Luke’s vivid prose combined with his careful attention to Mary’s story commended him as the obvious choice to be the sole portrayer of Mary’s true likeness.

Painter, physician, gentile or Jew, companion of Paul, writer of the Third Gospel and Acts: What one thinks about the identity of Luke rests in large part on one’s assessment of these traditions. Did the early church have information about the identity of the author of Luke and Acts that is no longer available to us? Or did someone looking to identify the otherwise anonymous author simply deduce Luke’s identity from the text of the New Testament?

Presumably the gospel’s prologue, where the author seems to identify himself as a second-generation Christian, excludes identifying the author as an apostle (and thus making the choice of a “lesser” figure almost inevitable). The “we” sections in Acts demand someone who was a companion of Paul, and Luke the beloved physician emerges as a likely—though, importantly, not the only—candidate.

On the other hand, we must consider the stability of the tradition that identifies Luke as the author. Strictly speaking, the Third Gospel is an anonymous document, making no claims about its authorship. That all testimony agrees in identifying the author as a relatively obscure man named Luke is no trivial matter. Regardless of his identity, the author of Luke and Acts has left for us works that remain two of the most significant contributions by an early Christian to our understanding of the founder of Christianity and its first followers.

Much of the material presented here is derived from the first chapter of “Luke: Physician, Painter, and Patron Saint,” an as yet unpublished volume, coauthored with Heidi J. Hornik, entitled Illuminating Luke: The Infancy Narrative in Italian Renaissance Painting. I would like to express my appreciation to Dean Wallace Daniel of the College of Arts and Sciences, Baylor University, for granting me time to work on this essay.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Roy W. Hoover, “How the Books of the New Testament Were Chosen,” BR 09:02.

The Greek word

See Florent Heintz, “Polyglot Antioch,” AO 03:06.

Endnotes

See esp. Charles H. Talbert, Literary Patterns, Theological Themes, and the Genre of Luke-Acts, Society of Biblical Literature Monograph Series (SBLMS) 20 (Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1974); I. Howard Marshall, “Acts and the ‘Former Treatise,’” The Book of Acts in Its Ancient Literary Setting (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1993), pp. 163–182.

There have been challenges to the assertion of common authorship, largely on the grounds of vocabulary and style. Most notable is Albert C. Clark (The Acts of the Apostles: A Critical Edition with Introduction and Notes on Selected Passages [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1933], p. 394), who, after a detailed study of the syntax and style of Luke and Acts, concluded “that the differences between Lk. and Acts were of such a kind that they could not be the work of the same author.” Wilfred L. Knox countered Clark’s arguments in a carefully constructed rebuttal, however. Like Clark, Knox deals with the use of particles, prepositions, conjunctions and other small parts of speech. Knox reasoned: “It may seem that to discuss such matters is to waste time over minute trivialities; but a man can be hanged for a fingerprint” (The Acts of the Apostles [Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1948], p. 3; also pp. 4–15, 100–109).

Other interesting linguistic dissimilarities between Luke and Acts have been more recently observed by Stephen H. Levinsohn, H. Levinsohn, Textual Connections in Acts,SBLMS 31 (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1987),who incidentally is not primarily interested in the authorship question.

Modern scholars generally affirm the position of common authorship held by the early church, though the implications of that common authorship are not always clearly distinguished. See, for example, Mikeal C. Parsons and Richard I. Pervo (Rethinking the Unity of Luke and Acts [Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1993]), who suggest that we must distinguish among various kinds of unity (e.g., narrative, generic, theological) when speaking of the unity of the Lukan writings and also allow for the possibility that some elements of discontinuity between the two writings might arise from time to time.

See especially John Knox, Chapters in a Life of Paul, revised by the author and edited with introduction by D. R. A. Hare (Macon, GA: Mercer Univ. Press, 1987), and Paul Vielhauer, “On the ‘Paulinism’ of Acts,” in Studies in Luke-Acts: Essays Presented in Honor of Paul Schubert, ed. Leander E. Keck and J. Louis Martyn (Nashville: Abingdon, 1966), pp. 33–50.

The quotation is taken from Hobart’s cumbersome subtitle to The Medical Language of St. Luke: A Proof from Internal Evidence that “The Gospel according to St. Luke” and “The Acts of the Apostles” Were Written by the Same Person, and that the Writer was a Medical Man (1882; reprint, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1954). Hobart’s thesis was supported by the eminent scholar Adolf von Harnack (Luke the Physician, trans. J.R. Wilkinson [New York: Putnam, 1909]).

Henry J. Cadbury, The Style and Literary Method of Luke (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1920), p. 50.

See esp. Joseph Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, Anchor Bible 28 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981), vol. 1, pp. 35–59; and Luke the Theologian: Aspects of His Teaching (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist, 1989), pp. 1–26. Fitzmyer offers a carefully and critically nuanced defense of the tradition: Luke the physician was an uncircumcised Semite and sometime companion of Paul.

The “Anti-Marcionite” character of this prologue is dubious, and some date the text to the fourth century. See E. Gutwenger, Theological Studies 7 (1946), pp. 393–406.

Epiphanius, Panarion 51.110. A variant reading in the fifth-century manuscript Codex Bezae inserts the phrase: “And there was much rejoicing, and when we were gathered together” at the beginning of Acts 11:28, which makes this verse another “we” passage set in Antioch. This variant reading almost certainly derives from the tradition associating Luke with Antioch.

David Tiede, Promise and History in Luke-Acts (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress, 1980), p. 7; see also Jacob Jervell, Luke and the People of God (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 1972).

See esp. Richard Bauckham, “For Whom Were Gospels Written?” in Bauckham, ed., The Gospel for All Christians: Rethinking the Gospel Audiences (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), pp. 9–48.

Cited by the 14th-century writer Nicephoros Callistes Zanthopulos; see Jean-Paul Migne, Patrologia Graecae 86.165.

For more on the traditions of Luke as painter, see Eunice Howe, “Luke, St.,” in Dictionary of Art, ed. Jane Turner, 34 vols. (New York: Grove’s Dictionaries, 1996), vol. 19, pp. 787–789.

Dorothee Klein, St. Lukas als Maler der Maria: Ikonographie der Lukas-Madonna (Berlin: Oskar Schloss, 1933).

Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend, trans. William Granger Ryan, 2 vols. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1993), vol. 2, p. 251.

See Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria 8.3.62; Ad Herennium 4.39.51. The authors of the so-called Progymnasmata (rhetorical exercises for schoolboys) also commended the vividness, clarity and style of both the accomplished speaker and writer. According to the first-century C.E. author Aelius Theon, the “desirable qualities of a description are these; above all, clarity and vividness, in order that what is being reported is virtually visible” (Progymnasmata 7.53–55).