Why Did Joseph Shave?

Endnotes

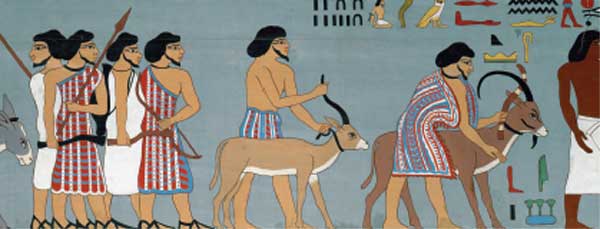

For discussions of the sources and composition history of the Joseph story, see the commentaries. For studies of its Egyptian background, see, in addition to the commentaries, D.B. Redford, A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph (Genesis 37–50) Vetus Testamentum Supplements 20 (Leiden: Brill, 1970), pp. 189–243; J. Vergote, Joseph en Égypt (Louvain, 1959); idem. “‘Joseph en Egypte’: 25 Ans Apres,” in S. Israelit-Groll, ed., Pharaonic Egypt: The Bible and Christianity (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1985), pp. 289–306; W. Dietrich, “Die Josephserzählung als Novelle und Geschichts-schribung: Zugleich ein Beitrag zur Pentateuchfrage,” Biblisch-Theologische Studien 14 (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1989), pp. 60–69. None of these works mention the Egyptian background of Joseph’s shaving.

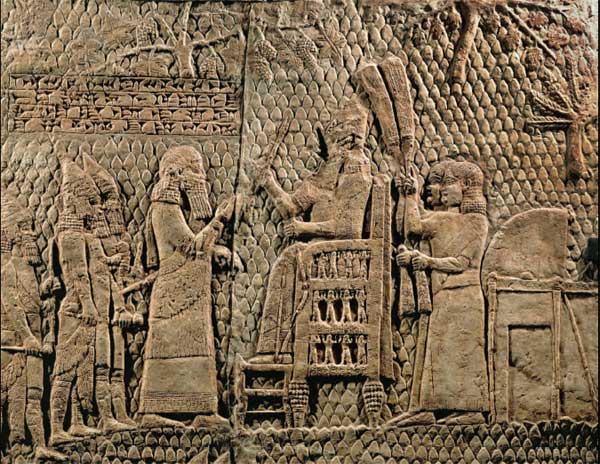

David Ussishkin, The Conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib (Tel Aviv: The Institute of Archaeology, 1982), Fig. 71, pp. 88–89.

A.M. Blackman, “Purification (Egyptian),” in A.B. Lloyd, ed., Gods, Priests, and Men: Studies in the Religion of Pharaonic Egypt by Aylward M. Blackman (London: Kegan Paul International, 1998), pp. 3–21, esp. p. 6.

S. Sauneron, The Priests of Ancient Egypt, tr. David Lorton, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press, 2000), pp. 35–40.

For a discussion of the types of Egyptian priests and their ranks, see my The Priest and the Great King: Temple Palace Relations in the Persian Empire. Biblical and Judaic Studies from the University of California, San Diego 10 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2004), pp. 56–59.

M. Weinfeld, “Instructions for Temple Visitors in the Bible and in Ancient Egypt,” Scripta Hierosolymitana 28 (Egyptological Studies) (1982), pp. 224–250. The populace at large could not enter, only the priests Sauneron, The Priests of Ancient Egypt, pp. 35–40.

M. Alliot, Le Culte D’Horus Á Edfou au Temps des Ptoléméés (Cairo: Institut Français d’archéologie Orientale Bibliothéque d’Étude, Vol. 22, 1949), pp. 184–185.

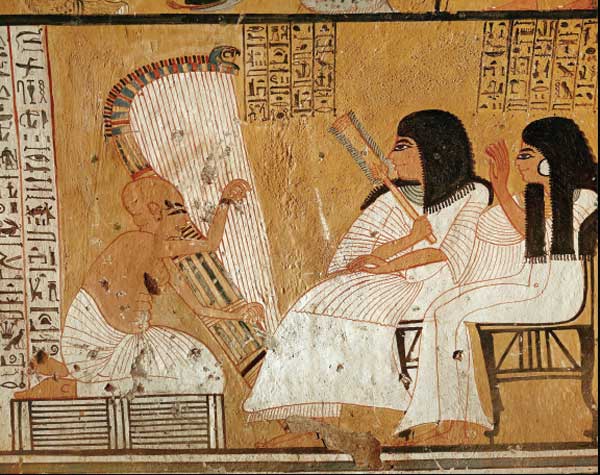

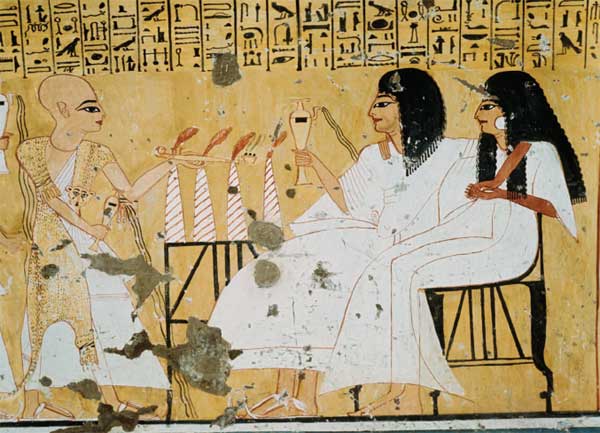

M. Andrews, “The Tomb of Foreman Inherkhau,” www.touregypt.net/featurestories/inherkhaut.htm. Male beauty (as shown by the representations of Pharaoh) included a full head of thick, black shoulder-length hair (L. Green, “Beauty,” Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt [Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001], pp. 167–171). Medical papyri show the concern for this standard of beauty. They provide numerous recipes for hair tonics, both to cover the grey in order to achieve the desired deep black, as well as to treat thinning hair and spotted or male-pattern baldness. See H. Kamal, A Dictionary of Pharaonic Medicine (Cairo: The National Publication House, 1967), pp. 213–214. On the use of wigs to achieve this standard of beauty, see below, note 14.

H. Junker, “Vorschriften für den tempelkult in Philä,” Analecta Biblica 12 (1956), pp. 151–160. When the reference is to adult males, this is the only interpretation that is appropriate to all the occurrences. See W. Westendorf, “Noch einmal: Das Wort ‘m‘ — Knabe/Jüngling/Unbeschnittener/Unreiner,” Göttinger Miszellen 206 (2005), pp. 103–110; Pace E. Feucht, “Pharaonische Beschneidung,” in S. Meyer, Egypt—Temple of the Whole World/ Ágypten—Tempel der Gesamten Welt: Studies in Honour of Jan Assmann (Leiden: Brill, 2003), pp. 81–94.

Male circumcision was common among the ancient Egyptians, boys being circumcised in groups when they reached puberty. See “Circumcision—Who Did It, Who Didn’t and Why,” BAR 20:04, and C. de Wit, “La Circoncision chez les anciens Egyptiens,” Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 90 (1972), pp. 41–48, and more recently, W. Westendorf, “Noch einmal: Das Wort ‘m‘.”

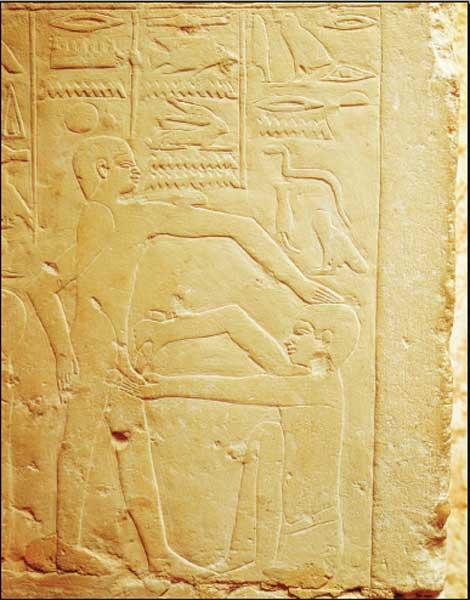

The Sixth Dynasty (c. 2340–2140 B.C.E.) tomb of Ankh-ma-Hor at Saqqara, www.nocirc.org/symposia/second/larue.html

Hilary Wilson, “The Priest,” in Wilson, People of the Pharaohs: From Peasant to Courtier (London: Michael O’Mara Books Ltd., 1997), pp. 97–119, esp. p. 106. Priests were not resident in the temple, but were organized into phyles, taking their turn in the temple only every fourth month. The rest of the time they lived normal lives with their families. See Blackman, “Purification (Egyptian),” p. 10; D. Meeks, “Pureté et Impureté: Égypte,” in Dictionnaire de la Bible—Supplément, vol. 9 (Paris, 1979), pp. 430–451, esp. p. 441.

The fact that most men rotated in and out of the priesthood meant that they were shaved bald one month out of every four—and this at a time when the standard of male beauty was deep black shoulder-length hair! (See endnote 10.) For those men (and this was most upper class men) the only way to achieve the standard of male beauty was the wig. Wigs were thus the fashion, and were worn on public occasions and at banquets, often woven into the existing short hair. See J. Fletcher, “Hair,” British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1995), pp. 117–118.

This is also true of “God’s Wife”, the daughter of either the high priest of Amun who ruled Thebes or (from the 23rd dynasty) of the king. After the fall of the 20th dynasty, these Wives of the God ruled Thebes themselves. See Blackman, “Priest, Priesthood (Egyptian),” pp. 125–126.

On the relationship between “cleanliness” and food prohibitions, see P. Galpaz-Feller, “The Stela of King Piye: A Brief Consideration of ‘Clean’ and ‘Unclean’ in Ancient Egypt and the Bible,” Revue Biblique (1995), pp. 506–521.

Sauneron, The Priests of Ancient Egypt, p. 37, citing Berlin Griechische Urkunden vol. V, p. 76.

D.E. Fleming, The Installation of Baal’s High Priestess at Emar, Harvard Semitic Studies 42 (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992), pp. 180–182.

On the shaving of Levites, see B.A. Levine, Numbers 1–20, Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday, 1993), pp. 273–274. On shaving rites in general, see S.M. Olyan, “What Do Shaving Rites Accomplish?”

A. Blackman, “Priest, Priesthood (Egyptian),” in Lloyd, ed., Gods, Priests, and Men, pp. 117–144, esp. pp. 117–118.

“Palast” Lexikon der Ägyptologie.Hrsg. von Wolfgang Helck und Eberhard Otto (Wiesbaden,O. Harrassowitz,1972), p. 643.

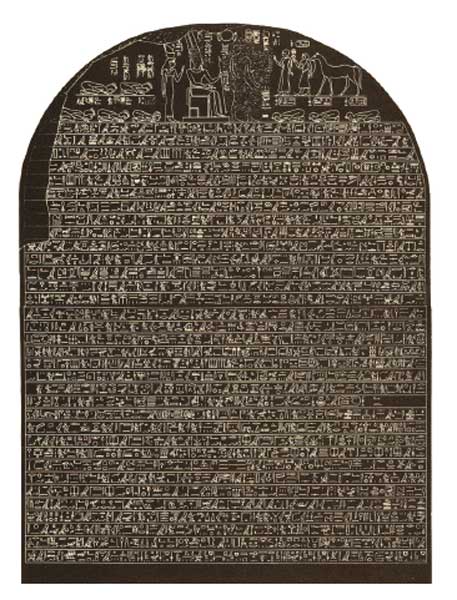

Miriam Lichtheim, “The Victory Stela of King Piye,” in Lichtheim, ed., Ancient Egyptian Literature: Vol III—The Late Period (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), pp. 66–84.

This article has benefited immensely from conversations with Aakyo Eyma, Eugene Cruz-Uribe, Donald Redford, Joachim Friedrich Quack, and Penina Galpaz-Feller. In addition, Professor Eyma has read an early version of the manuscript and made invaluable suggestions. All remaining errors are my own.