Will the Real Josephus Please Stand Up?

What went through the mind of Flavius Josephus as he stepped through his doorway into the brilliant sunshine of the Roman summer in 75 C.E.? Now 38 years old, he was beginning to write The Jewish War—a history of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–74 C.E.). A year earlier, the last rebels had been vanquished at Masada. In 70 C.E., Roman legions had burned Josephus’s home city, Jerusalem, along with the magnificent Temple where he had occasionally served as priest. It was only six years since his namesake, Titus Flavius Vespasianus (Vespasian), had seized ultimate control of the Roman Empire.

Immediately following the war, captured Judeans had flooded the slave market. Vespasian had issued a commemorative coin series proclaiming “Judea Captive!” He and his son Titus (who later succeeded Vespasian as emperor) had marched through the streets of Rome in spectacular triumph, surrounded by symbols of Josephus’s defeated homeland. Perhaps Josephus even witnessed mob reprisals against his compatriots living in Rome, such as those that occurred in other Mediterranean centers.1 In any event, it cannot have been the best of times to be a Judean in Rome.

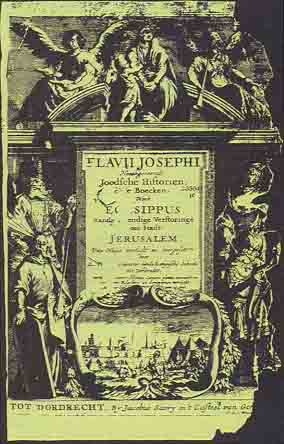

Josephus was himself the definition of paradox: a Jewish priest who had once led part of the bloody revolt against Rome but who had somehow managed to gain imperial favor. At some point in the preceding years, this man, born Yosef bar Mattathyahu, had assumed the Roman-sounding name Flavius Josephus. Now he lived very comfortably, with Roman citizenship, in Vespasian’s private house. The ruling family of Flavius would further honor him by depositing three of his books in their library and commissioning a statue of him.

Surprisingly, Josephus’s situation in postwar Rome has not often been a matter of scholarly interest, even though it may be the key to understanding his work. Rather than reading his works as the coherent expression of an ancient Jew, critics have typically mined them for data about Judean politics, geography, economics and so on. This approach has been frequently reflected in the pages of BAR, where Josephus has often been cited but never introduced to the reader as anything other than “the first-century Jewish historian.”

Josephus tells the story of his life in books 2 and 3 of his seven-volume Jewish War and in his short autobiographical Life. Until the last two decades or so, many scholars found this self-portrait so repulsive that they had little reason to consider Josephus’s writings sympathetically.

According to the Jewish War, Josephus knew that it was futile to fight the Romans, but he was nevertheless hand-picked in November of 66 C.E. to lead the Galilean front. Though a reluctant combatant, he turned out to be a resourceful general, he says. When the Romans besieged the fortified town of Yotapata the next summer, he fought with bravery and ingenuity but then tried to escape by deceiving the townsfolk into thinking that he was leaving to get help. When this effort failed and the Romans took the town, Josephus was led “by some divine providence” to hide in a deep pit. There, God chose him, prophet-like, to announce God’s will to the Romans. He tried to convince his fellow hideaways to surrender to the Romans; they, however, preferred mass suicide to surrender. When he was unable to dissuade them, he “trusted himself to God” and proposed instead a chain of mercy killings, in which his soldiers drew lots to see who would kill his fellow. Josephus allowed that it would be unconscionable for the two final links in the chain to save themselves after the others had died. However, finding himself to be one of the two remaining soldiers, he persuaded his comrade that they should both surrender to the Romans.

It gets worse.

Once in Roman custody, Josephus requested an audience with then-general Vespasian. Josephus then cheerfully announced that Vespasian and his son Titus, though not part of the ruling Julio-Claudian family that had taken the name “Caesar,” would nevertheless become “Caesars.” When Vespasian subsequently became emperor, he rewarded Josephus lavishly.

The story in the Life, which Josephus wrote much later (in about 94 C.E.) to fend off criticism of his command in Galilee, seems to incriminate him further. Now he portrays himself as consistently opposed to the revolt. He went to Galilee, he writes, as part of a team whose purpose was to induce the locals to lay down their arms (thus, not as a general in the first instance). When he did gradually assume a leadership role in the war, he still tried in every way to make peace with the Romans. In the process he routinely deceived his own people about his motives. Most readers have accordingly come to regard him as a congenital liar, a traitor and a shameless opportunist.

When scholars at the turn of the century began to inquire seriously into Josephus’s purposes in writing, this view of his character carried over into their assessments. For example, Richard Laqueur argued in 1920 that Josephus’s Jewish War was a piece of imperial propaganda, intended to pacify other nations who might be tempted to initiate war with Rome—particularly the Parthians, the Romans’ longtime enemy to the east—by showing what had happened to the Judeans. Laqueur’s evidence seems persuasive, at least on the surface.2 Josephus wrote the Jewish War while living under imperial favor in Rome soon after the revolt. The work itself routinely flatters Vespasian and Titus. Moreover, Josephus tells us that an original, Aramaic version of the Jewish War was in fact addressed to Parthian readers. Finally, the work includes an excursus on Roman military training, which he says he includes to console those beaten by the Romans and to dissuade others who might be tempted to revolt.

An obvious problem with this view of the Jewish War is posed by Josephus’s later writings. Everyone agrees that his 20-volume Antiquities of the Jews (completed in 93 or 94 C.E.) and 2-volume Contra Apion (completed in about 100 C.E.), which represent some 75 percent of his literary output, vigorously defend Jewish culture. But if Josephus wrote the Jewish War as a lackey of his Roman masters, how could he have composed these later treatises in such a different spirit? Laqueur concluded that Josephus must have changed his allegiances between the Jewish War and Antiquities of the Jews. Some students of Laqueur proposed that the middle-aged Josephus was seized with guilt for his earlier conduct (betrayal and the propagandistic Jewish War) and so wrote his later works in a spirit of repentance. Others argued that the relentless opportunist simply tried to find a home within the Jewish community because the accession of Domitian as emperor (in 81 C.E.) had ended his cozy relationship with the Flavian house.3

In the last two decades, things have begun to change, although one can still find examples of the old model. This shift has been facilitated by the appearance of a proper concordance to Josephus and electronic searching tools, as well as by the effort to create a better Greek text from the various surviving manuscripts (Josephus’s originals, like most other ancient texts, are long gone). These developments have revealed an unexpected consistency of language and theme across Josephus’s whole body of writing, from the Jewish War and Antiquities to his Life and his final work, Contra Apion. This realization begs for a reappraisal of his entire legacy as an author.

In revising our view of Josephus, we ought not to begin with his life and character. The reason is simple. His life and character are not directly accessible to us; they cannot be observed. All we have are his literary descriptions of himself. It has not been sufficiently recognized that Josephus, like his contemporaries, wrote under rhetorical constraints that were quite different from ours. I would argue that the literary descriptions of his actions, which strike us as so repugnant, were intended to arouse admiration in his day. No author would deliberately set out to make himself look terrible. A widespread literary tradition, made popular by the hero of Homer’s Odyssey, viewed tricksters, deceivers and survivors as objects of bemused admiration. So long as a person had a noble goal—in Odysseus’ case, his return to faithful Penelope at Ithaca—his lies and deceptions (read: resourcefulness under duress) were perfectly forgivable; they might even be praised by a wily god like Athena, though the more severe philosophers would disagree.

Given the entertaining character of Josephus’s self-descriptions, it is much more likely that he invented them to appeal to the reader rather than simply to relate what happened. But if he made up or massaged these accounts to entertain his readers, presenting himself as the reluctant warrior who used his wits to survive, it is pointless for us to impugn his character on this basis. Aside from these artfully constructed stories, which include most everything from his birth and pedigree in Judea to his surrender in Rome, we know very little of his life. Therefore, rather than using his life to interpret his writings, we ought to begin with the writings themselves.

The Jewish War, Josephus’s account of the First Jewish Revolt, was written in Rome between 75 and 79 C.E.a The work begins with a lengthy introduction that is often ignored. But ancient Greek authors were much concerned with introductions. That was where the original reader was expected to get a sense of the book’s aim and scope. That is where we should begin, too.

From the introduction we gather that, far from writing Roman propaganda, Josephus presents his effort as a quintessentially Jewish work. He wants to defend the surviving Jews from slander on account of the war. His opening claim is that several others have already written accounts of the war but that those accounts are motivated either by flattery of the Romans or by hatred of the Judeans—either way, bad for the Jewish cause. These other histories, he says, portray the Romans as great while disparaging the actions of the Judeans. Josephus, by contrast, presents himself as a proud and authentic Judean priest who fought in the revolt and so is in a unique position to tell the truth.

Thus, according to Josephus himself, his work aims to refute the propagandistic accounts in circulation. To be sure, his claims to having a uniquely Jewish vantage point seem calculated to market his work. But they also seem true, for he would have been in a better position than Roman authors to recount both sides of the conflict.

Are these statements a thin veneer for Roman propaganda? Not likely. Although we do not possess those anti-Jewish histories with which Josephus took issue, we do have earlier comments by Greek and Roman authors concerning Jews, as well as later, second-century remarks on the revolt of 66–74 C.E. These works probably reflect sentiments that were also current immediately after the conflict. Earlier authors often accused the Jews of being antisocial (separating themselves from others) and atheistic (not recognizing the common deities);4 Jews thus opposed the essential Roman values of piety toward the gods and justice toward one’s fellows. The later Roman writers claim, predictably, that the revolt was merely an expression of the rebellious Judean character5 and that the Roman victory was the inevitable triumph of exasperated Roman gods.6

Since Josephus’s Jewish War tackles precisely these claims, it appears that they were being made by the historians whom Josephus criticizes.

Josephus argues that the revolt was instigated by a few power-crazed Judean “tyrants.” Rebellion is antithetical to the Jewish character, which, he insists, prizes piety and justice more than does any other nation.7 Although pressed beyond reason by brutal Roman governors (this is no whitewash of the Romans!), the Judean people and their leaders still did not desire revolt.8 Certainly, when they were finally drawn into the conflict by the mischievous rebels, they fought with valor; they were not the motley crew disparaged in the Roman accounts.9 But they and their legitimate leaders really did desire peace. Second, the fall of Jerusalem resulted not from the victory of Roman gods but from the Judean God’s punishment of the nation for its own sins—especially for the rebels’ pollution of the Temple.

This all-powerful God controls world history, granting even the Romans their sovereignty at the present time for His own purposes.

Josephus’s attempt in a foreign language (Greek) to remove the ground from Roman bragging and anti-Judean slander while living in postwar Rome was a literary challenge if ever there was one.

His account of the war begins with the story of the Jewish Hasmonean dynasty (170–37 B.C.E.), more than two centuries earlier. Why? In part, he shows that the once proud Judean nation could fight for noble causes, as it heroically rescued its autonomy from the tyranny of the Seleucids—the former enemies of Rome. The brutal Seleucid king Antiochus IV was driven by “ungovernable passions,” but like David against Goliath, Judah Maccabee, in 168 B.C.E., took on the entire Seleucid army. The Judeans had excellent rule during the first part of the Hasmonean reign; it was only the later Hasmonean kings who squandered their heritage and thereby necessitated Roman intervention.

Josephus emphasizes that the Romans have always found in the Judeans respected friends and allies. Even as Pompey captured Jerusalem in 63 B.C.E., he was filled with admiration for their courage and devotion to their tradition. The prime example of friendly Judean-Roman relations was the world-famous King Herod of Judea. His loyal support for a succession of Roman rulers—including Mark Antony and Augustus—created the basis for a cooperation that endured until the eve of the revolt. In the Jewish War, Josephus describes Herod as courageous, pious and benevolent to all.10 Herod’s detractors are malicious knaves, and his ultimate downfall is attributed to a domestic tragedy set in motion by his wives and children.

In the middle of volume 2 of the Jewish War, we come to Josephus’s career and the events that set the revolt in motion. These included, he claims, the emergence of reckless false prophets and “bandits,” the establishment of a rebel party, the extreme cruelty of the later Roman governors, rising tensions between Judeans and Greeks in coastal Caesarea, and heinous crimes committed by the Roman governor Gessius Florus, including the massacre of a Jerusalem crowd. In the context of describing the rebels’ beginnings, Josephus includes his famous description of the Essenes, Pharisees and Sadducees.

This last passage provides a clear example of the need to read Josephus’s material in context. Scholars have been almost completely preoccupied with comparing this section, as if it were simply a block of facts about the Essenes (taken by Josephus from some other source), with the Dead Sea Scrolls. For example, they try to fit Josephus’s claims about the Essenes’ dress, demeanor and living arrangements with passages in the scrolls. Although Josephus claims that the celibate Essenes are found in every town,11 scholars commonly link his celibate Essenes with the Qumran settlement and his marrying Essenes, whom he mentions almost as an afterthought, with the authors of the Damascus Covenant. All of this ignores the thrust of Josephus’s narrative. The narrative is not a balanced account from some objective source, but a carefully crafted story that he includes in order to contrast the Essenes’ discipline and peaceful disposition, which are truly Jewish, with the rebels’ recklessness. Josephus’s statement about the Essenes’ observance of “piety toward God and justice toward humanity”12 is not a simple observation about their practice. It reflects his typical language, for elsewhere he claims that all the great Jewish leaders of the past, including John the Baptist, taught these basic virtues. The entire passage is a literary creation.

Dragged into the revolt against his will, Josephus says, he put up a brave defense for about six months as commander of the Galilee but finally succumbed to the Roman siege of Yotapata in July of 67 C.E. Since he surrendered so early, was a prisoner in Caesarea until Vespasian was confirmed as emperor late in 69 C.E. and then spent a few months in Alexandria, he was removed from much of the Judean conflict. He returned with Titus for the final siege of Jerusalem, from March to September of 70 C.E., but even then he had no firsthand knowledge of what occurred within the city walls. In writing his narrative, he depended on the field notes of Roman generals and the Jewish king Agrippa II, oral reports from soldiers and Judean escapees, and possibly some of those earlier histories that he refutes.

Josephus’s fragmentary knowledge does not prevent him from describing events with great rhetorical force. He recounts a lengthy speech given by King Agrippa II to prevent war, in which the main themes coincide perfectly with Josephus’s own views: the divine favor and invincibility currently enjoyed by Rome, the distinction between cruel Roman governors in Judea and the benevolent central Roman government, the importance of preserving the Temple’s sanctity and the danger of reprisals against Judeans living elsewhere.13 Fighting among rebel factions, Josephus asserts, led to the murders of both rebel leaders and chief priests as well as the unconscionable Sabbath massacre of the surrendering Roman garrison, after which the “moderates” knew that the city would be subject to divine punishment. Cestius Gallus, governor of Syria, came close to quashing the revolt in its infancy, but God had already determined to punish the Judeans. Nero’s dispatch of Vespasian to fight the war was evidence of the Judean God’s shaping of the destiny of the empire.

When the various rebel factions fled to Jerusalem before the advancing Roman armies, they profaned all that was holy. They converted the sacred Temple into their private fortress, elected a simpleton as high priest and invited the notoriously belligerent Idumeans to join them. The latter arrived and promptly murdered the Temple guard in the sacred courts, along with the main opponents of war—the chief priests Ananus and Jesus (not Jesus of Nazareth; Jesus was a common name at this time). Josephus, proud priest that he claims to be, sees their murders as major causes of divine punishment of the city. Paradoxically (here comes the flattery), the foreign generals who served as the agents of God’s punishment were more sympathetic toward ordinary Judeans and more respectful of the Temple than were the Judean rebels.14 When Josephus stood with the Romans in the siege of Jerusalem, he pleaded with the rebels that scripture and tradition were completely opposed to their lawless aggression; elsewhere he alludes to mysterious prophecies of the city’s doom in the event of rebellion.15 Josephus makes the consistent case that scripture justifies current Roman rule.

Accordingly, the rebels’ actions led to catastrophe. To set up a compelling backdrop for the destruction, Josephus paints a picture of the former glory of Jerusalem and its magnificent Temple. About three million Jews, who had traveled to Jerusalem for the pilgrimage festival of Passover, were trapped in the city when the Roman siege began, Josephus says; famine struck and, in combination with the rebels’ plundering, led to starvation and even cannibalism.16 Omens foreshadowed the destruction of the Temple: The massive eastern gates opened by themselves, a sacrificial cow gave birth to a lamb, terrifying scenes were observed in the heavens and mysterious voices were heard announcing the divine departure from the Temple. These omens of destruction were confirmed by the peculiar figure of Jesus, son of Ananias, who patrolled the streets of Jerusalem day and night for more than seven years, pronouncing doom on the city in Jeremianic verse. Finally, after overcoming the city walls, the Romans entered the Temple and set fire to it—unwittingly accomplishing the purging ordained by the Judean God. This action was taken against the express will of Titus, who even tried to extinguish the fire.

Thus Josephus has elaborately proven his thesis: Most Judeans were drawn into the war reluctantly, by the arrogant and un-Jewish behavior of a few tyrants; the fall of Jerusalem was their punishment for sins against God’s holy sanctuary.17 By the time of the Jewish War, the rebels had already been punished, so there is no longer any basis for anti-Judean sentiment. All other surviving Judeans, whose tradition prizes civility, are innocent of war guilt.

We cannot know what effect this argument had on Josephus’s readers. His claim that Vespasian and Titus endorsed the work seems likely. It was in their interest that postwar hostilities cease and life return to normal. It may be that the book relieved the burdens of other Diaspora Jews, perhaps even saved Jewish lives. And that might help to explain the otherwise curious popularity of the name Flavius (but not Vespasian or Titus) among Roman Jews from the end of the first century.18

Whereas the conventional view envisions the Jewish War as Roman propaganda and Antiquities as Jewish apologetic, we should instead conclude that the Jewish War is already a bold effort to defend the Jews. Antiquities and Contra Apion more forthrightly advocate Judaism for interested gentiles. Thus we no longer need to drive a sharp wedge between Josephus’s two major works. There is no reason to believe that his motives and perspective changed between the Jewish War and Antiquities. The later work shows no hint of embarrassment over the earlier one; on the contrary, Josephus begins Antiquities by reflecting on his Jewish War with great pride.19 Indeed, he claims he had originally planned to include the more ancient history contained in Antiquities with his account of the revolt, but the project became unwieldy.20 He regularly refers readers of Antiquities back to the Jewish War for more detailed information, and his later works refer to both accounts together.21 In spite of modern criticism, Josephus himself evidently thought that he wrote both works in the same spirit.

That Antiquities assumes a gentile readership is clear from statements in the preface and numerous comments on and explanations of Jewish customs throughout the work. These prospective gentile readers are not to be critics, however, but rather outsiders already deeply interested in Judean culture—which is suggested by the fact that Josephus expects them to pore through 20 volumes! And his tone is not at all defensive; he magnanimously wishes all “lovers of truth” to know that the constitution established by Moses, under which the Judeans live, is the finest in the world. It alone offers the happiness that people vainly seek in other constitutions and philosophies because it is in perfect harmony with the laws of nature, as old as life itself, philosophically pure and practically effective. To a society worried about rising crime, Josephus declares that the imageless God revered by the Judeans does not let vice go unpunished or virtue unrewarded—unlike the gods of “mythology” (his readers’ gods!), who actually encourage vice by their immoral behavior.

Where would Josephus have found a gentile audience so interested in Jewish culture? Roman authors who have occasion to mention Judeans, even incidentally, refer to their proselytizing activity with surprising frequency.22 This activity was notable because when a gentile embraced Judaism he or she embarked upon a complete change of lifestyle—involving circumcision for males, a different diet and calendar, and new friendships and standards of public conduct. This was quite unlike the addition of another form of gentile piety to one’s religious life, such as reverence of Isis or Dionysus. In the aftermath of the revolt, moreover, the already considerable social costs of conversion to Judaism can only have become more forbidding. Although we do not know precisely which Greek-speaking gentiles Josephus expected to sit through his lengthy treatise (how many of us are willing?) and endure assaults on their traditional piety, these readers no doubt included potential converts.

Almost all of Antiquities describes events outside of Josephus’s personal experience, from Creation until the eve of the revolt in 66 C.E. For volumes 1–11, his main source is scripture, in various Greek and possibly Semitic versions as well as “apocryphal” material. He has a wide knowledge of oral traditions about the characters of the Bible, which he splices into his narrative at appropriate points, and he liberally cites Greek and oriental authors. He retells Judean history in linear fashion, by conflating parallel sources (for example, Samuel/Kings and Chronicles) and omitting most prophetic or wisdom material.

He also turns Judean national history into the history of great men.23 That allows him to develop his thesis, for he can identify those who obeyed the laws and those who did not, and show how the virtuous found happiness and the evildoers punishment, how the Judeans brought great benefits to the world, and how God in his watchful care (pronoia) actively supervised the whole project. Josephus’s emphasis on individuals also permits him to elaborate on psychological motives: envy, hatred, lust, revenge, pride, shame, reason and grief.24

Abraham was the first person to conceive of the deity as one, a conception widely shared by the philosophically minded of Josephus’s day. Abraham originally taught science to the renowned Egyptians.

Joseph lectured Potiphar’s wife on the evils of unchecked passion; Joseph’s own virtuous life, disciplined by reason, brought him great happiness.

An Egyptian scribe predicted the birth of Moses, who would “surpass all men in virtue.” The baby’s survival in the basket showed that God’s intervention preempted human malice. The child Moses far excelled his peers in wisdom, stature and beauty—and was far from being the leper or charlatan of Egyptian literary imagination.25 While still in the Egyptian court, he won a courageous battle against the mighty Ethiopians and so saved the cowardly Egyptians. In summarizing Moses’ laws, Josephus makes a few adjustments to the Bible as we know it but thinks that his understanding is dictated by the text.26

David was the embodiment of virtue, a valiant and just king who could also discern the future. He quickly repented of his one transgression, the Bathsheba affair, which nonetheless cost him dearly.

Solomon was the epitome of the philosopher-king so desired by Plato. Possessed of an intelligence unmatched by any other person, Solomon excelled even the magnificent Egyptians. Thoroughly familiar with the healing secrets of nature, he was also an effective exorcist, and his ancient prescriptions account for the Judeans’ modern-day expertise in this area. Nevertheless, Solomon died out of favor with God because in old age he transgressed the laws. His transgression paved the way for the division of the kingdom and a string of wicked kings.

Josephus is quite taken with the exilic prophets Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel, for all three lived in a time like Josephus’s own, after Jerusalem and the Temple had been destroyed (by the Babylonians) under God’s direction as punishment for the nation’s transgressions. Moreover, Jeremiah and Ezekiel were both priests, like Josephus. Jeremiah, also like Josephus, was accused of being a traitor by his compatriots for counseling submission to foreigners who served God’s purposes. Josephus also saw himself in Daniel, who prospered in the court of a foreign ruler while steadfastly maintaining his ancestral tradition, living like a true philosopher and entrusting himself to God’s protection from the schemes of the envious. Most important, all three prophets, especially Daniel, predicted with clarity the events of world history down to Josephus’s own day, including both Roman imperial power and the end of that dominion.27

Josephus rounds out his Biblical paraphrase with a leisurely retelling of the Esther story. It supports his thesis perfectly: The wicked Persian Haman set out to annihilate the Judean nation, but God punished Haman and his co-conspirators with the very penalty that they had designed for the Judeans. God’s control of all history is indisputable.

With the Seleucid domination in Palestine (198 B.C.E.), Josephus begins a period that he has already dealt with in the Jewish War. Now, however, he has space to deal with the Hasmoneans and Herodians at length, and his emphasis is different. Taking advantage of new sources for the Hasmoneans, he quietly revises many small points in his earlier portrayal. Similarly for Herod, Josephus now has an independent biography of the king, Herod’s own memoirs and numerous state documents dealing with Judean-Roman relations—all this in addition to Herod’s court historian Nicolaus of Damascus, who had served as Josephus’s main source in the Jewish War. Rather than making Herod a prime example of good Judean citizenship, Josephus now makes him an example of God’s ever-watchful care for humanity. He still acknowledges Herod’s courage, loyalty to the Romans and occasional acts of piety, and he still marvels at Herod’s Temple, though the description differs in some respects from that of the Jewish War; but he now sprinkles his Herod story with searing indictments of the king for his transgression of those laws that are the subject of Antiquities.28 This is background for Josephus’s repeated claim that Herod’s personal miseries and horrible death were actually divine punishment for his evil.29 Herod’s life thus conspicuously illustrates the effectiveness of the Judeans’ God.

Various stories round out Josephus’s account of Jewish history, suggesting further that Antiquities was addressed to a friendly gentile audience, including potential converts. About a quarter of the final volume, for instance, is filled with an account of the conversion to Judaism of the royal house of Adiabene in Parthia. The dilemma posed by the story is whether the new Adiabenian king, Izates, who has become devoted to Jewish ways, should go through with circumcision and full conversion—thus putting him at great personal risk from his subjects. Izates decides to be circumcised, trusting himself to the protection of the Jewish God. Josephus takes pains to demonstrate that God intervened repeatedly to thwart plots on Izates and to bring the king prosperity. Presumably, the gentile reader interested in Jewish ways but worried about the social costs of conversion is to take comfort from this shining example.30

Josephus’s final known work, Contra Apion, written around the year 100 C.E., addresses the patron of Antiquities, Epaphroditus, and assumes the same kind of benevolent gentile readership. Josephus begins by reflecting that despite his efforts in the Antiquities, his great history of Jewish culture, some people continue to slander Jewish tradition. The malicious slanderers have influenced some readers of his book to doubt the antiquity of the Judeans. So he will now tackle in a systematic way the main slanderers, one of whom was an influential Egyptian named Apion (hence the traditional name of the book). Josephus’s critique of the Jews’ detractors is sharp-witted and often humorous. He notes, for example, that Apion, who so savagely ridiculed circumcision, was himself forced to be circumcised as the result of a genital ulcer.31

Josephus’s detailed critique is valuable for many reasons. He includes extensive citation of his opponents’ views, which are often the only fragments of those authors that have survived. He reveals much about the then-current state of literary and historical criticism, and his analyses became a model of apologetic writing for the Christian church, which preserved them.

The final quarter of Contra Apion is devoted to an extended celebration of Jewish culture and its many benefits to the world. Once again, he aptly summarizes Jewish law, pointing out its just and humane character and arguing for its superiority to all other systems, which are ineffective in directing human affairs. He observes the great influence of Jewish ideas and customs in the world. And he repeatedly elaborates upon the warm welcome given by Jewish culture to those foreigners who wish to make it their own—not casually visiting it as interesting exotica, but fully adopting it.

No matter how one reads Contra Apion, it is hard to square this work with the old view of Josephus as an opportunist. This is a passionate and skilled advocacy of Judaism. For that reason, those who insist that Josephus was a quisling often propose that he did not really write the work but took it over more or less bodily (prefixing his own introduction) from Alexandrian Jewish literature. But this seems a desperate stratagem. The work is replete with Josephan language and themes, and his systematic destruction of slanders about Jewish antiquity was already woven into the historical text of the Antiquities.32

If there is no plausible way to avoid Josephus’s authorship of this compelling work, then we must reckon with a Josephus who went to extraordinary lengths to promote Jewish interests.

When Josephus walked the streets of Rome in the summer of 75 C.E., newly at work on his Jewish War and living in the very seat of anti-Judean resentment, his mind must have turned to the malicious accounts that connected the bloody revolt with the Judean character. He wrote to absolve surviving Judeans from war guilt by blaming the revolt on a very few reckless and un-Jewish rebel leaders who had been duly punished. He wanted to show that the Judeans had in fact been longtime allies of the Romans and exemplary world citizens. These Judeans recognized that the kingdoms of the world rose and fell under the control of their God, and so the current fortune of the Romans should not be resisted. He accordingly rejected the notion that the Roman gods had won a victory, for in his view it was the all-seeing Judean God who used Rome for his purposes. Even the Roman Titus acknowledged God’s aid.33 Josephus could not have known that this bold literary effort would appear to later generations as a work of betrayal.

Reading the Jewish War in context allows us to dispense with improbable hypotheses about Josephus’s repentance and new resolve to promote Judaism in the Antiquities and Contra Apion. Rather, those later works merely continue the effort begun in the Jewish War. Having tried to end reprisals by removing the worldwide Jewish population from war guilt (in the Jewish War), he addressed those gentiles who continued to be interested in Judean history and culture. For this group, he portrayed Judaism as the only effective system of law and life in existence. In Contra Apion Josephus reached sublime heights, couching a systematic refutation of old anti-Jewish slanders in resounding statements about the power and influence of Jewish culture. In both of these later works, he celebrates the benefits of conversion.

This unified reading of Josephus’s works requires a complete rethinking of conventional views. I do not claim to know anything directly about his character. He is long dead, so we cannot observe him. Surely, however, we should not begin with some imaginary reconstruction of his character and use that to reject his writings. It makes much more sense first to appreciate his writings, which are all that remain of him, for what they are: a bold defense and advocacy of Judaism.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

Reprisals in other areas play a large role in Josephus’s chronicle of the revolt (The Jewish War 2.399, 457–498; 7:41–62, 361–369).

Laqueur’s interpretation received widespread publicity and support, especially through the qualified endorsement of Henry St. John Thackeray, Josephus’s first translator for the Loeb Classical Library. Thackeray’s 1928 lectures on Josephus became the standard introductory textbook, Josephus: The Man and the Historian (New York: Ktav, 1967 [1929]).

This reading of Antiquities of the Jews was developed by the late Morton Smith of Columbia University; see “Palestinian Judaism in the First Century,” in Israel: Its Role in Civilization, ed. Moshe Davis (New York: JTSA/Harper & Brothers, 1956), pp. 67–81, esp. 74–75.

See Molly Whittaker, Jews and Christians: Graeco-Roman Views (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1984), pp. 14–130.

Cf. Harry J. Leon, The Jews of Ancient Rome, rev. ed. (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1995), pp. 119–120.

Louis H. Feldman has studied each of the main Biblical characters in Josephus’s story. See the list of the resulting articles in his Jew and Gentile in Antiquity: Attitudes and Interactions from Alexander to Justinian (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1993), pp. 595–596.

The groundbreaking study was Harold W. Attridge’s The Interpretation of Biblical History in the “Antiquitates Judaicae” of Flavius Josephus (Missoula, MT: Scholars, 1976). See also Feldman, “Use, Authority and Exegesis of Mikra in the Writings of Josephus,” in Mikra: Text, Translation, Reading and Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity, ed. Martin J. Mulder and Harry Sysling (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1988), pp. 455–518.

Josephus, Antiquities 10.206–210; cf. 4.114–117. Today we realize that Daniel and Second/Third Isaiah (Isaiah 40–66) were probably written after the events they claim to predict. But scholars who see Josephus as an opportunist may forget that Josephus lived long before such critical insights. (Daniel’s Hasmonean date was first proposed by the third-century C.E. philosopher Porphyry.) Josephus believed that Daniel and Second Isaiah were written centuries before the events they predicted (Josephus, Antiquities 10.276–281; 12.319–322). He had also read or heard that great world leaders such as Cyrus and Alexander had happily acknowledged the merit of Judean Scripture.

Josephus, Antiquities 16.1–5, 150–159, 179–188, 311–312, 362–365, 395–404; 17.150–151, 168–171, 180–181, 191.

Cf. Tacitus, Histories 5.5; Juvenal, Satires 5.14.96–106; Celsus in Origen, Against Celsus 5.41; and Cassio Dio, Roman History 67.14.12.