Folk Religion in Early Israel: Did Yahweh Have a Consort?

Does the Hebrew Bible provide an adequate account of the religious beliefs and practices of ancient Israel? The answer is a resounding no. The Bible deals extensively with religion and even seems preoccupied with the subject; and it does provide a record of a developing monotheism associated with the reforms of the Judahite kings Hezekiah (727–698 B.C.E.) and Josiah (639–608 B.C.E.). But it is ultimately limited as a source of information about the great variety of Israelite cult practices.

The Hebrew Bible is not an eyewitness account. Rather, it was edited into its present form during the post-Exilic period (beginning in the latter part of the sixth century B.C.E.), centuries after the events it purports to record. It thus reflects the religious crisis of the Diaspora community of that time. The Bible is also limited by the fact that its final editors—the primary shapers of the tradition—belonged to orthodox nationalist Yahwist parties (the Priestly and Deuteronomic schools)a that were hardly representative of the majority in ancient Israel. The Bible, as a theologian friend reminds me, is “a minority report.” Largely written by priests, prophets and scribes who were intellectuals and religious reformers, the Bible is highly idealistic. It presents us not so much with a picture of what Israelite religion really was but of what it should have been.

The Bible is an elitist document in another sense as well: It was written and edited exclusively by men. It therefore represents their concerns—those of the Establishment of the time—to the virtual exclusion of all else. In particular, the Bible’s focus is on political history, the deeds of great men, public events, affairs of state, and great ideas and institutions. It almost totally ignores private and family religion and women’s cults; “folk religion,” the cultic practice of the majority in ancient Israel and Judah, is passed over almost without a word.1

If the biblical texts alone are an inadequate witness to ancient Israelite religion, where else can we turn for information?

Modern archaeology has brought to light a mass of new, factual, tangible information about the history and religion of ancient Israel. This material is incredibly varied, almost unlimited in quantity, and has the advantage of being more objective than texts—that is, less deliberately edited. Archaeology also possesses a unique potential for illuminating folk religion, in contrast to the official religion of the texts, because material remains, unlike the texts, do not favor elites; and material remains present evidence of concrete religious practices rather than abstract theological formulations. Archaeology does not simply tell us what priests and clerics think the people should have done; it provides an account of what they actually did.2 The abundance of recent archaeological data forces us to rewrite all previous histories of ancient Israelite religion and, in particular, to address the issue of whether Israel was truly monotheistic during the monarchical period.

Cultic Sites in Ancient Israel

Several recently excavated sites in Israel have produced materials that are clearly cultic in nature, some of them no doubt what the Bible is referring to when it condemns bamot, or “high places” (for example, 2 Kings 23:8). We shall move from north to south and from the period of the Judges to the monarchy, that is, from Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.) through Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.E.).

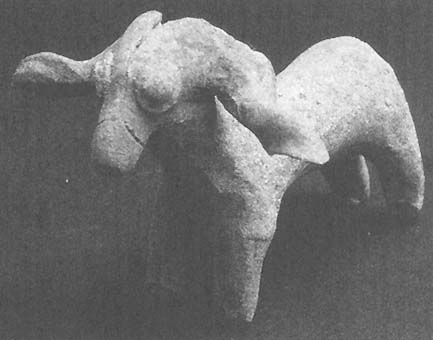

The Bull Site

A small open-air hilltop sanctuary in the tribal territory of Manasseh, dating to the 12th century B.C.E., was excavated in 1981 by Amihai Mazar. It features a central paved area with a large standing stone (a biblical massebah) and an altar-like installation, the whole enclosed by a wall. The only material recovered consists of a few early Iron Age I sherds, some fragments of metal and of a terra-cotta offering stand, and a splendidly preserved bronze zebu bull. The bull, possibly a votive statue, is almost identical to a bronze bull found by Yigael Yadin at Hazor in a Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.) context. The principal epithet of El, the chief male deity of the Canaanite pantheon in pre-Israelite times, was “Bull.” Thus the Manasseh shrine or sanctuary—the only clear Israelite cultic installation yet found from the period of the Judges—was probably associated not with Yahweh but with the old Canaanite deity El.3

Dan

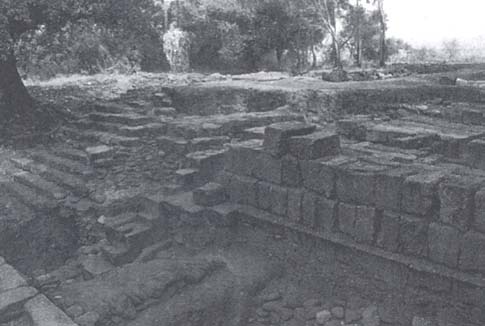

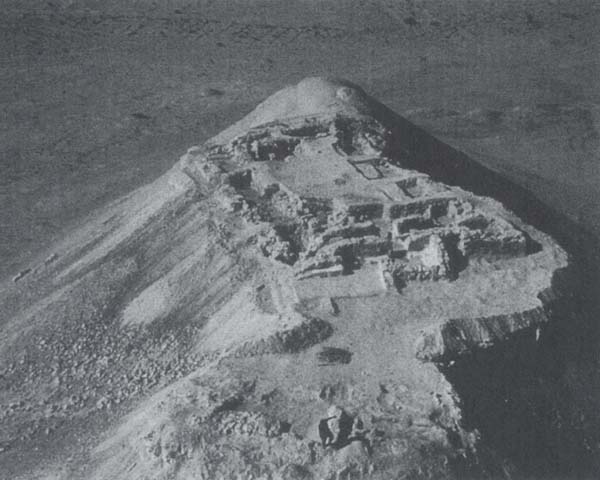

The distinctive mound of Tel Dan, one of the early capitals of the northern kingdom of Israel, has been excavated since 1966 by Avraham Biran. At the highest point on the northern end of the mound is an impressive installation from the tenth to ninth centuries B.C.E. It consists of a large podium, or altar, approached by a flight of steps, all in fine ashlar (chisel-dressed) masonry, and an adjoining three-room structure, probably an example of the biblical lishka

Other materials found within the precinct include an olive oil press, used for liturgical purposes; large and small four-horned altars, which are alluded to in several biblical passages; a bronze-working installation; a fine priestly scepter; seven-spouted lamps; a naos (a household temple model or shrine); several dice; and male and female figurines. This cult installation lasted into the seventh century B.C.E., dramatically illustrating that “non-Establishment” cults did exist in the early monarchy as well as throughout Israel’s and Judah’s history.4 When mentioned at all, these cults were condemned by the southern Israelite writers and editors of the Bible, who were loyal to the Temple in Jerusalem.

Tell el-Far‘ah (North)

Referred to as Tirzah in the Bible, Tell el-Far‘ah (North) served as the temporary capital of the northern kingdom of Israel in the early ninth century B.C.E. The site was excavated by Père Roland de Vaux from 1946 to 1960. Just inside the city gate is a massebah and an olive press—no doubt part of the “gate-shrine” referred to in the Bible. De Vaux also found numerous tenth- and ninth-century B.C.E. female figurines (some of the earliest known Asherah figurines) and a terra-cotta naos. This naos, to judge from other contemporaneous examples, would have had a deity, or a pair of deities, standing in the doorway; one of them would have been Asherah, the Canaanite mother goddess. Tell el-Far‘ah (North)’s Canaanite temple model/shrine was in use during the very period of the Solomonic Temple in Jerusalem, where, at least according to the biblical writers, all worship was centralized.5

Megiddo

Another example of supposedly prohibited local object of worship is a household shrine found in tenth-century B.C.E. strata at Megiddo, a Solomonic regional capital in the north. The shrine consists of several cult vessels and small four-horned limestone altars, of a type found at many Israelite sites. The altars were probably used for incense offerings, which were integral to the official worship described in the biblical texts (though the Bible does not refer specifically to small horned altars, only to much larger examples, as in 1 Kings 1:50–51).6

Taanach

A few miles southeast of Megiddo lies its sister city, Taanach, where even more substantial tenth-century B.C.E. cultic remains have come to light. A shrine there contains a large olive press, a mold for making terra-cotta female figurines like those from Tell el-Far‘ah (North), and a hoard of astragali, or knucklebones, used in divination rites.

More remarkable are two large multitiered terra-cotta offering stands. One, found long ago by a German excavation, depicts ranks of lions. The other, from the American excavations of Paul Lapp, has four tiers and is probably best understood as a temple model. The top tier, or story, shows a quadruped carrying a winged Sun-disc on its back. The next row down depicts the doorway of the temple, which stands empty, perhaps to signify that the deity of this house (in Hebrew, beit [house] means “temple” when used in connection with a deity) is invisible. The third row down has a pair of sphinxes, or winged lions, one on each side, which probably represent the biblical cherubim depicted in the Solomonic Temple (see 1 Kings 8:6–7).

The bottom row of this Taanach stand is startling: It has two similar flanking lions, with a smiling nude female figure standing between them, holding them by the ears. Who is this enigmatic figure? She can be no other than Asherah, the Canaanite mother goddess. Asherah is known throughout the Levant in this period as the “Lion Lady,”7 and she is often depicted nude, riding on the back of a lion. One side of a 12th- or 11th-century B.C.E. inscribed arrowhead from the Jerusalem area reads, “servant of the Lion Lady”; the arrowhead probably belonged to a professional archer, who thus named his patroness.8 On the other side of the arrowhead appears the archer’s name, Ben-Anat, or “son of Anat”; Anat is another name for the old Canaanite mother goddess. We can only wonder what a model temple possibly depicting an invisible Yahweh and a very visible Asherah was doing at Israelite Taanach in the days of Solomon and the Jerusalem Temple. This is a remarkable piece of ancient Israelite iconography. As we shall see, however, there is an abundance of evidence for the cult of Asherah in Israel during the biblical period.

Jerusalem

Of the many pieces of archaeological evidence of religion from Jerusalem, only a few can be singled out here. A rock-cut tomb on the grounds of the Dominican École Biblique et Archéologique Française, long known but only recently dated to the eighth to seventh centuries B.C.E., has benches for the corpses that feature headrests carved in the shape of the Hathor wig. This distinctive bouffant wig was worn in Egypt by Qudshu, the Egyptian cow goddess, who was identified with the popular Canaanite goddess Asherah. Thus, even in Jerusalem, the spiritual center of biblical religion, a Judahite woman could be buried with her head resting in a wig that was strongly associated with the Canaanite goddess Asherah.9

Another tomb from the late seventh century B.C.E., found near St. Andrew’s Church of Scotland, contained similar benches with headrests, as well as two tiny silver scrolls. Both scrolls are inscribed with passages found in the priestly blessing of Numbers 6:24–26. These scrolls date to about 600 B.C.E., making them by far our oldest surviving source of a biblical text—at least four centuries older than any of the Dead Sea Scrolls. This bit of Scripture, however, was used not for edification but for “magic,” which was strictly forbidden in orthodox Israelite religion. What we have here is a biblical text that was engraved on silver, rolled up, put on a string and worn around the neck as an amulet—a good luck charm.10 And there are many more archaeological examples of such magical or superstitious practices, from both Israel and Judah, some of them invoking foreign deities, such as the Egyptian gods Bes and Osiris. Bible scholars have paid little attention to archaeological finds of this sort, but they should: Such objects illustrate the prevalence of the folk religion so vigorously condemned in the Bible as idol worship, or the use of miples

Beersheba

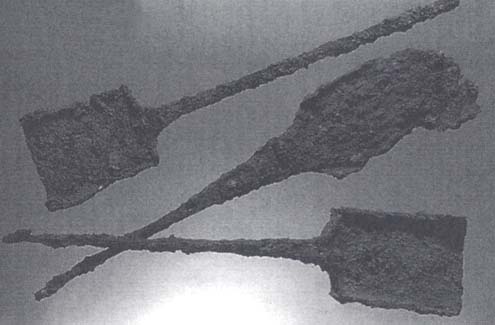

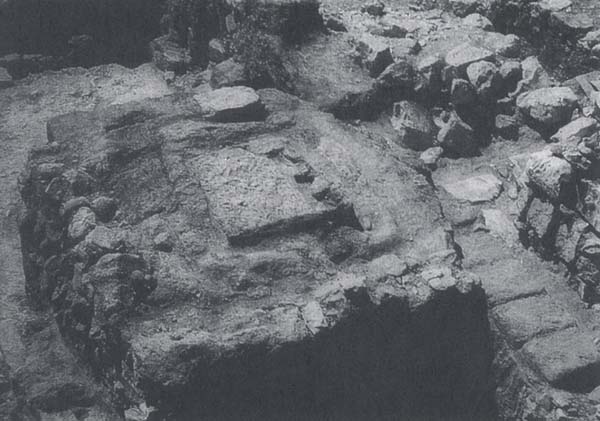

Marking the southern limits of the settled zone in monarchical times (as in the biblical phrase “from Dan to Beersheba”), Beersheba was excavated by Yohanan Aharoni from 1969 to 1975. Among the most spectacular finds were several large dressed blocks of stone that make up a monumental four-horned altar. Over five feet tall, this is one of only two examples of such large altars that archaeologists have brought to light (the other is at Dan). Its stones, however, were not recovered in situ but were found in secondary use, built into the walls of later storehouses near the city gate.

Where did the Beersheba altar originally stand, and why was it dismantled? Aharoni argued that his “basement building”—a large structure set into an unusually deep foundation trench that obliterated lower levels—was the site of what had once been a large temple, where the altar had originally stood. If so, the temple may have been destroyed during the eighth-century B.C.E. religious reforms of Hezekiah, who pulled down the high places and their altars (2 Chronicles 29–32). As though to confirm Aharoni’s theory, a large krater (a two-handled pot) found nearby is inscribed in Hebrew, qo

The Beersheba finds are the first actual archaeological evidence confirming the religious reforms of Judahite kings. They also provide evidence of the need for such reforms: The religious activities denounced by the biblical prophets as the worship of “foreign gods” were evidently widespread.11

Arad

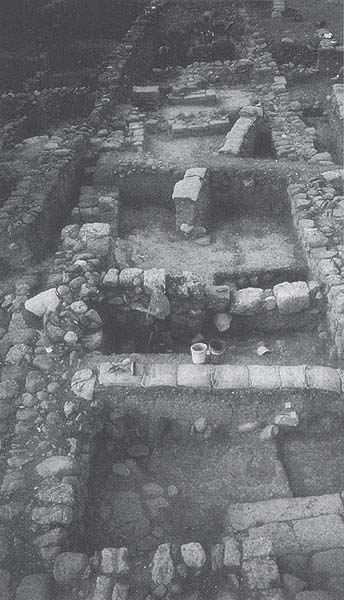

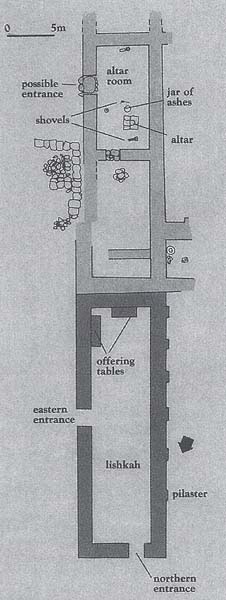

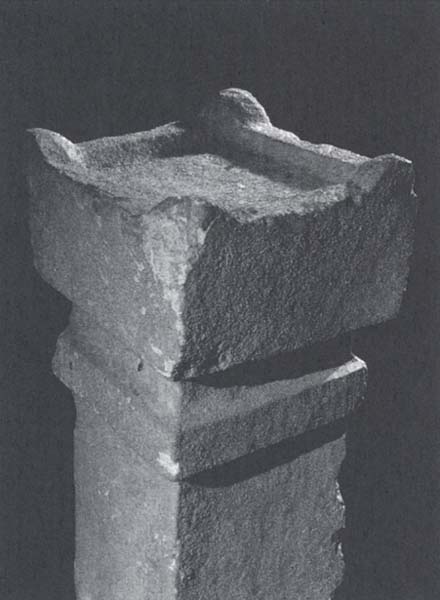

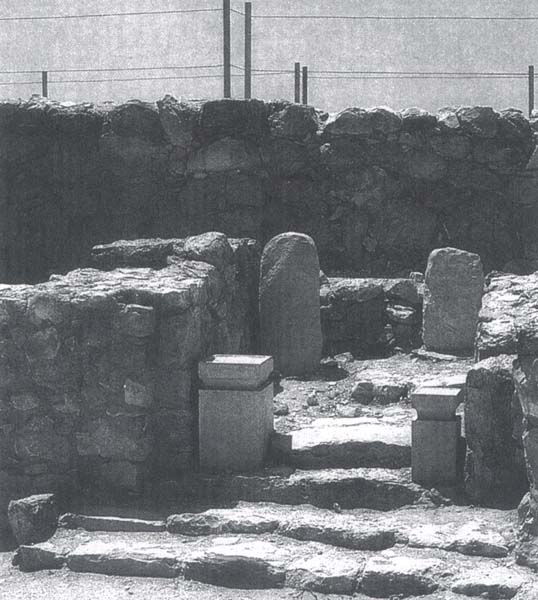

Not far to the east of Beersheba is Arad, a small Judahite hilltop fortress and sanctuary also excavated by Aharoni. The dating and interpretation of the various tenth- to sixth-century B.C.E. phases remain controversial because of faulty excavation methods and the lack of final reports. Yet for our purposes, the main points are clear. One corner of the ninth- to eighth-century B.C.E. walled citadel is occupied by a three-room temple, very similar in plan to the partly contemporaneous Temple in Jerusalem. The outer area (the biblical ‘ula

The temple’s main central chamber (the biblical heikhal) is a smaller room with low benches, undoubtedly for the presentation of offerings. The inner chamber (the biblical dvir, Holy of Holies) is a still smaller niche. The steps to this inner chamber hold two stylized horned altars containing an oily organic substance that suggests incense. Against the chamber’s back wall rest two sacred standing stones (masseboth) with traces of red paint, one of them smaller than the other.

Since these altars and standing stones had been carefully laid down and floored over in a later stage of this building, Aharoni argued that the Arad temple presents additional archaeological evidence of the reforms of Hezekiah (or, according to other scholars, Josiah), who abolished local sanctuaries in favor of the Jerusalem Temple. I would go further: Both the bronze lion and the pair of standing stones show that Asherah, the Lion Lady, was worshiped alongside Yahweh at Arad, perhaps for a century or more, until this became a problem for religious reformers. Is this the sort of syncretism that the prophets decried? Or was Asherah so thoroughly assimilated into the Israelite cult from early times that most Israelites considered her to be native to their beliefs and practices—that is, associated with Yahweh, and perhaps even his consort?12

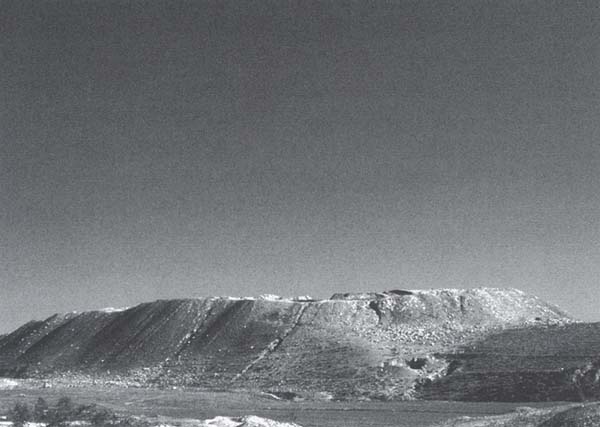

Kuntillet ‘Ajrud

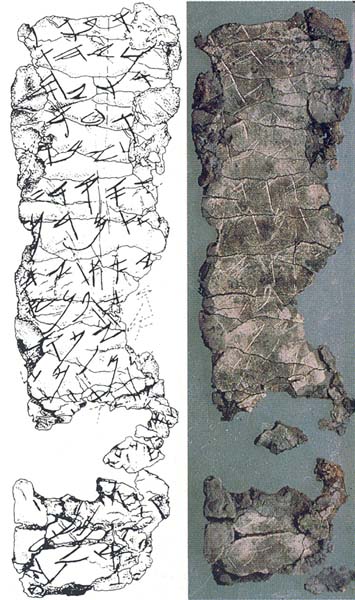

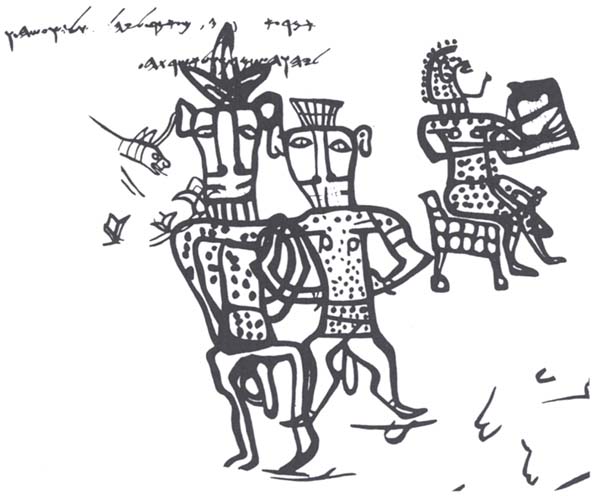

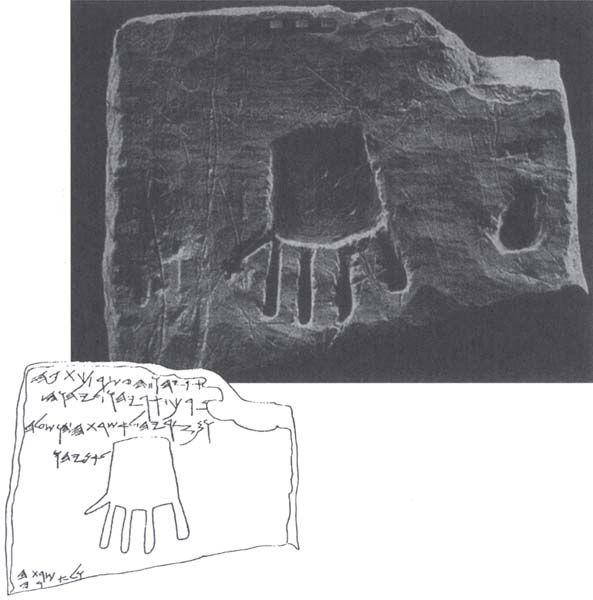

As though to answer this question, dramatic textual evidence of Asherah has recently come to light at two sites. Kuntillet ‘Ajrud is a hilltop caravanserai, or stopover station, in the remote eastern Sinai desert. It was discovered by the British explorer Edward Palmer in 1878 and excavated in 1978 by the Israeli archaeologist Ze’ev Meshel. Again, the finds are controversial and published only in preliminary reports. Yet the impact of the material known so far is revolutionary for our understanding of ancient Israelite religion. The main structure at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, from the eighth century B.C.E., is a large rectangular fort with double walls, corner towers and a central open courtyard—similar to other known Iron Age fortresses in the Negev. The entrance area, however, is unique. It is approached through a white plaster esplanade, which leads into a passageway flanked by two plastered side rooms with low benches, behind which are cupboard-like chambers. These chambers are clearly favissae, storage areas for discarded votives and cult offerings, many examples of which have been found at Bronze Age and Iron Age sanctuaries. The benches are obviously not seats but platforms for offerings, a type of installation that also has many parallels.

Any doubt about the existence of a shrine here in the ‘Ajrud gateway (and surprisingly enough, some scholars do doubt it) is removed by even a cursory examination of the finds. These include a large stone votive bowl inscribed in Hebrew: ”(Belonging) to Obadaiah son of Adnah; may he be blessed by Yahweh.” On several large storage jars are painted motifs and scenes: a processional of strangely garbed individuals; the familiar “tree of life,” with flanking ibexes; lions; and striking representations of the Egyptian good-luck god Bes and a seated half-nude female figure playing a lyre, whose distinctive lion-throne suggests that she is a goddess (as we also find gods and goddesses seated on lion-thrones elsewhere in the ancient Near East). A Hebrew inscription on one storage jar is a blessing formula, ending with the words “by Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah.”

Some biblical scholars understand the Hebrew word ’a

The archaeological evidence from the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud texts alone should force us to rethink much of what scholars have written about “normative” religion, about monotheism, in ancient Israel. The ideal religion formulated late in the Hebrew Bible is one thing; actual religious practices are another, reflecting a popular religion that we would scarcely have known about if not for the accidents of archaeological preservation and discovery.13

Khirbet el-Qôm

The ‘Ajrud texts help corroborate the meaning of an eighth-century B.C.E. Judahite tomb inscription near Hebron, which I discovered in 1968. Although parts of the reading are difficult and controversial, the best interpretation goes something like this:

’Uriyahu the Prince; this is his inscription.

May ’Uriyahu be blessed by Yahweh,

For from his enemies he has saved him by his Asherah.

Virtually all scholars now agree that the reading “by his a/Asherah” in line 3 is certain; the phrase is identical to that at ‘Ajrud and presents the same problems of interpretation. Nevertheless, considering that we have only a handful of ancient Hebrew inscriptions from tombs or cultic contexts, the fact that two of them mention “a/Asherah” in the context of a blessing is striking. It would appear that in nonbiblical texts such an expression was common, an acceptable expression of Israelite Yahwism throughout much of the monarchy. Thus Asherah was commonly thought of as the consort of Yahweh, or perhaps as a hypostasis of Yahweh—that is, a personification of some aspect of Yahweh (his wisdom or presence, for example). The orthodox textual tradition has, in effect, purged the Bible of many original references to the goddess Asherah, as well as downplayed the remaining references to the point that many are scarcely intelligible.14

Artifacts of the Israelite Cult

In addition to the cultic sites, we now have many individual artifacts that reflect the variety of religious beliefs and practices in ancient Israel and Judah.

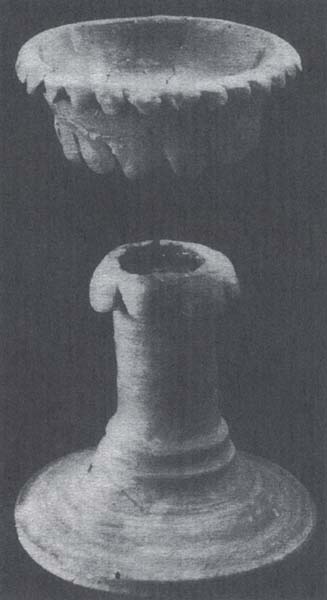

Offering Stands

Dozens of Israelite terra-cotta offering stands date from the 12th to the 7th century B.C.E. They continue a long Bronze Age tradition of cult stands throughout the ancient Near East, which, as we know from seal impressions and paintings, were used to present gifts of food, drink and perhaps incense to the gods. Such rituals became part of the standard cult in ancient Israel, as we know from many biblical texts, so there must have been at one time a fairly elaborate paraphernalia.15 It is therefore curious that the Hebrew Bible never even hints at the use of offering stands. Is it possible that the biblical writers were unaware of such widespread practices? Or did they simply believe that the sharpest sign of disapproval would be to disdain mentioning them?

Some of the Israelite offering stands are rather plain, with no obvious symbolic significance. But others, like the elaborate tenth-century B.C.E. Taanach stand, are full of Canaanite religious imagery. One of the most enigmatic is a 12th-century B.C.E. stand from Ai, an Israelite site from the period of the Judges. This stand has numerous fenestrations, or “windows,” probably to facilitate incense burning; it also features a curious row of well-modeled, human feet, which protrude from the bottom. A foot-fetish cult?16 In any case, the omission of any reference whatsoever in the Hebrew Bible to these common offering stands, when the texts are so preoccupied with sacrificial rituals, should give us pause. What are the biblical writers and editors describing: actual religious practices in ancient Israel or their own idealized, theologized reconstruction of what should have taken place?

Altars

Some four-horned limestone altars, like the one from Beersheba, are very large. But most—and at least 40 are now known—are miniature, from about 1 foot to 3 feet high. These small horned altars, dating from the tenth to the sixth century B.C.E., are found all over Israel and Judah in cultic, domestic and even industrial contexts.

Although the significance of the horn-like projections at the four corners is uncertain, they may be connected with older Bronze Age bull cults well known throughout the eastern Mediterranean world. As we have noted, the title “Bull” was used for the deity El in the Canaanite pantheon. It is also significant that when the biblical writers want to describe the Israelites’ apostasy, they tell stories of the people setting up a bronze calf at Mt. Sinai or of Jeroboam erecting a golden calf in his newly established royal sanctuary at Dan (1 Kings 12:28, 29) after the death of Solomon and the secession of the northern tribes.

But once again the biblical writers and editors are completely silent: The texts contain no hint of these small horned altars, even though they were probably used for burning incense, a practice described in detail in the Bible. So what is going on? When the Bible describes local altars being torn down in religious reforms, it surely is not referring to these small, portable monoliths. But in that case, what is being referred to and why do the texts fail to give us any details? If they did, we might be better equipped to identify monumental altars, of which we have no certain examples, as well as the miniature varieties. As it is, the facts on the ground do not coincide with the biblical descriptions, indicating at the very least two differing perceptions, if not religious realities: that of the Bible’s writers and editors, and that of everyone else.17

Cult Vessels

Numerous exotic terra-cotta vessels and implements, many of them unparalleled, are best understood as cultic in nature. They were no doubt used for ritual purposes, even though the exact manner in which they were employed, as well as the rationale behind them, may elude us.

One class of such cultic vessels is the naos, or temple model, of which we have several Israelite examples. The naos continues a long Bronze Age tradition of household models and shrines, often with depictions of a deity or pair of deities standing in the doorway. The frequent representation of lions, doves and Hathor wigs suggests that these model shrines were used in the veneration of Asherah, perhaps by women at local shrines or in domestic cults.18

Another class of cult vessel is the kernos, or “trick-vessel,” closely connected with Cyprus and perhaps introduced into Israel by the Sea Peoples or the Phoenicians. These are usually small bowls with a hollow rim that conducts fluid; the rim communicates with hollow animal heads attached to the bottom of the rim. When filled with a liquid, such as olive oil or wine, these bowls can be tilted to make the heads pour or appear to drink. While some scholars dismiss kernoi as simply toys, it is more reasonable to presume that these complex, exotic vessels were used in the cult for libation offerings. Such offerings are frequently mentioned in biblical texts; but again there is no mention of kernoi or of any other libation vessels that we can identify archaeologically.19

Also common are terra-cotta zoomorphic figurines, especially from eighth- and seventh-century B.C.E. Judahite tombs. Most are quadrupeds, like horses (sometimes with riders), cows or bulls, but other farm animals are also portrayed (one depicts a three-legged chicken). Some of these animal figurines are hollow and may have served as libation vessels. Others are more enigmatic. The horse-and-rider figurines and the quadrupeds with Sun-discs on their heads have been connected with biblical references to Josiah cleansing the Jerusalem Temple of the “horses … dedicated to the sun” and “chariots of the sun” (see 2 Kings 23:11). This is an obvious allusion to Assyrian and Babylonian solar and astral cults, which probably made serious inroads into Israelite and Judahite religion in the eighth to sixth centuries B.C.E. and which met with strong prophetic condemnation.20

Archaeology has recovered many other terra-cotta items that almost certainly had a cultic function. Particularly common in tombs are miniature models of household furniture, such as chairs, couches and beds. They undoubtedly were meant to accompany the dead into the afterlife and thus must have had some religious (or magical) significance. The same is probably true of small stone-filled rattles. Like the kernoi, these rattles are sometimes interpreted merely as toys, but this view simply highlights our ignorance (or lack of imagination) in dealing with the ancient cult. On the other hand, some clay vessels, such as perforated tripod censors, obviously had a cultic function, and we must try to understand what that was.

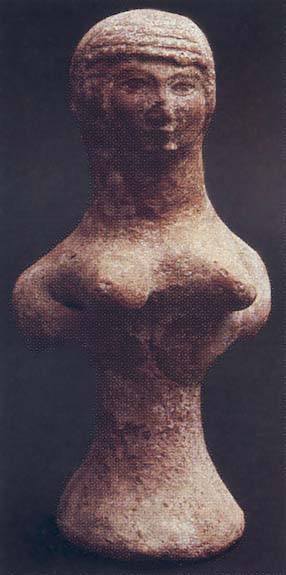

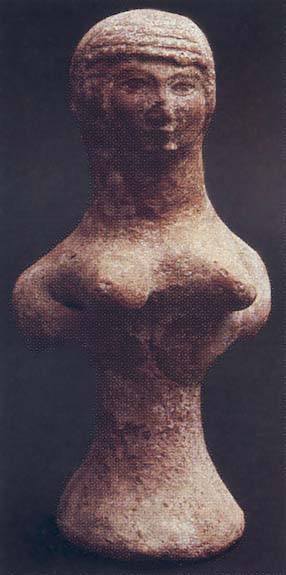

Figurines

By far the most intriguing cultic artifacts that archaeologists have recovered are more than 2,000 mold-made terra cotta female figurines, found in all sorts of contexts. They depict a nude female frontally; in the earlier examples, the figure often clutches a tambourine (or mold for bread) or occasionally an infant, whereas the later Judahite examples emphasize the figure’s prominent breasts. In contrast to the typical Late Bronze Age plaques depicting the mother goddess with large hips and an exaggerated pubic triangle, the Israelite figurines usually render the lower body simply as a pillar (thus the name “pillar figurines”); the pillar may represent a tree, a motif often connected with Asherah. These comparatively chaste portrayals may indicate that Asherah/Anat—the consort of the male deity in Canaan, with her more blatantly sexual characteristics—has now been supplanted by a concept of the female deity as principally a mother and a patroness of mothers. William F. Albright’s designation of these as “dea nutrix figurines” (nurturing goddesses) may be close to the mark. More recently, Ziony Zevit has aptly termed the female figurines “prayers in clay”—in this case, invocations to the mother goddess Asherah.21

It is surprising that so many biblical scholars and archaeologists are reluctant to conclude anything about these female figurines. Some claim they are merely toys—what I call the “Barbie doll syndrome.” Others say we simply do not and cannot know what they are. But their cultic connections are obvious. In ancient Israel most women, having been excluded from public life and the conduct of official political and religious functions, necessarily occupied themselves with domestic concerns. Predominant among these was reproduction—conception, childbirth and lactation. But there were also other extremely important concerns connected with rites of passage, marriages and funerals, and the maintenance and survival of the family. To be sure, men were involved in some of these domestic activities, but “the religion of hearth and home” fell mainly to women in Israel, as it did everywhere in the ancient world. It would not be surprising if Yahweh—portrayed almost exclusively as a male deity, preoccupied with the political history of the nation—seemed remote and unconcerned with women’s needs or even hostile to them. Thus half the population of ancient Israel, women, may have felt closer to a female deity and identified more easily with her. That deity would have been the old Canaanite mother goddess, who was still widely venerated in many guises in the Levantine Iron Age, and indeed much later.22

Toward a Definition of Popular Religion

With all this new archaeological evidence, we are prompted to ask: If the Bible records the religious practices only of elites, what did everyone else do? What is “popular religion?”23

One source of information is those texts of the Hebrew Bible that condemn certain religious practices. This involves a reasonable assumption, namely that the biblical prophets, priests and reformers knew what they were talking about—that the religious situation they complained about was real, not invented by them as a foil for their revisionist message. Ironically, in denouncing popular religious practices, the biblical writers unwittingly preserved chance descriptions of those practices. (That is not to say, however, that the same writers and editors in their zeal for orthodoxy did not deliberately suppress much information about popular religion that we should like to have.) Fortunately, archaeology has supplied much supplementary information; it has given us valuable clues on how to read between the lines of biblical texts.24

Consider two examples of how we might read the textual and the archaeological records together. Jeremiah 7:18 offers a telling description of what must have been a common family ritual, although one decried by the prophet: “The children gather wood, the fathers kindle fire, and the women knead dough to make cakes for the Queen of Heaven.” The latter is either Asherah or her counterpart Astarte (often coalesced, along with Anat, into a single figure in the Iron Age), of whom archaeology has supplied many, many images. An even fuller account of what was really going on in Judahite times is provided by the lengthy description in 2 Kings 23 of King Josiah’s reforms in the late seventh century B.C.E. Most biblical scholars have interpreted this passage as a piece of Deuteronomic propaganda, not as an accurate historical account of the king’s activities. But whether or not Josiah’s reform succeeded, the description of practices posing the need for such reform may have been based on the actual religious situation. It appears that it was; indeed, every single religious object or practice proscribed in 2 Kings 23 (for example, images of Asherah and offerings made on high places) can readily be illustrated by archaeological discoveries. The terminology of the text is not at all enigmatic; it is a clear reflection of the religious reality in monarchical times.25

Archaeology, supplemented by the biblical text, provides a highly accurate picture of popular religion. (1) It is noninstitutional, lying outside priestly control or state sponsorship. (2) Because it is nonauthoritarian, popular religion is inclusive rather than exclusive; it appeals especially to minorities and to the disenfranchised (almost all women in ancient Israel); in both belief and practice it tends to be eclectic and syncretistic. (3) Popular religion focuses more on individual piety and domestic or communal rhythms of life than on elaborate public ritual, more on cult than on intellectual formulations such as theology. (4) By definition, popular religion is less literate (though not any less complex or sophisticated) and thus may be inclined to leave behind more archaeological traces than literary records, more ostraca and graffiti than classical texts, more cultic paraphernalia than Scripture. (5) Despite these apparent dichotomies, popular religion overlaps significantly with official religion, if only by sheer force of numbers of practitioners; it often sees itself as equally legitimate, and it attempts to secure the same benefits as all religion does—the individual’s sense of integration with nature and society, health and prosperity, and ultimate well-being.

The major elements of popular religion in ancient Israel probably included the following: frequenting bamot and other local shrines; making images; venerating ’a

Why has the role of popular religion and the cult of the mother goddess in ancient Israel been neglected, misunderstood or downplayed by the majority of Bible scholars? One reason is that most Bible students share the elitist biases of the biblical writers themselves. Another reason is that the last 200 years of biblical scholarship have been largely shaped by Protestant scholars, who have preferred theology over cult (that is, over religious practices of any kind). Finally, there has existed a strong bias that only texts can inform us adequately on religious matters—that philology, rather than the study of material remains, should prevail. Yet archaeology is forcing us to revise our basic perception of ancient Israelite popular religion. Virtually expunged from the texts of the Hebrew Bible and all but forgotten by rabbinical times, folk religion enjoyed a vigorous life throughout the monarchy. This is not really surprising, since most Bible scholars now agree that true monotheism (not merely henotheism, the worship of one god without denying the existence of other gods) arose only in the period of the Exile or later.26

Even during the period of true monotheism, the popular cult survived. There are reflexes of the cult of the old mother goddess in later Judaism, such as the personification of divine Wisdom (Sophia) and the conception of the Shekinah, or effective presence of the divine in the world, which medieval texts of the Jewish Kabbalist sect sometimes called the “Bride of God.”27 Similarly, certain Christian doctrines may derive from a primitive memory of feminine manifestations of the deity; this can be seen in the development of the doctrine of the Holy Spirit—a more immanent, nurturing aspect of the transcendent God. Perhaps, too, the image of Asherah dimly survives in the elevation of Mary to “Mother of God,” a feminine intermediary to whom many less “sophisticated” Christians pray. In both Jewish and Christian circles, the mainstream, orthodox clergy has resisted these “pagan” influences, supporting instead rigorously monotheistic doctrines. But in popular religion, the old cults die hard. And when they finally do, archaeology may help to resurrect them.

Does the Hebrew Bible provide an adequate account of the religious beliefs and practices of ancient Israel? The answer is a resounding no. The Bible deals extensively with religion and even seems preoccupied with the subject; and it does provide a record of a developing monotheism associated with the reforms of the Judahite kings Hezekiah (727–698 B.C.E.) and Josiah (639–608 B.C.E.). But it is ultimately limited as a source of information about the great variety of Israelite cult practices.

The Hebrew Bible is not an eyewitness account. Rather, it was edited into its present form during the post-Exilic period (beginning in the latter part of the sixth century B.C.E.), centuries after the events it purports to record. It thus reflects the religious crisis of the Diaspora community of that time. The Bible is also limited by the fact that its final editors—the primary shapers of the tradition—belonged to orthodox nationalist Yahwist parties (the Priestly and Deuteronomic schools)a that were hardly representative of the majority in ancient Israel. The Bible, as a theologian friend reminds me, is “a minority report.” Largely written by priests, prophets and scribes who were intellectuals and religious reformers, the Bible is highly idealistic. It presents us not so much with a picture of what Israelite religion really was but of what it should have been.