How to Tell a Canaanite from an Israelite

I have been accused of organizing this entire session solely to have the opportunity of introducing Bill Dever. (Laughter.) And I want to deny that. That’s not the only reason. But it certainly is a pleasure for me to introduce an old friend with whom I have had some public disagreements. And I suppose for those of you who are aware of this, I should not simply gloss over them, but tell you that we are old and close friends despite our public professional disagreements. Basically, I think that is something that is over. It involved the use of the term “biblical archaeology.” I thought it was a good and credible and continually viable term. Bill, at one point in his career, thought we ought to abandon it. The ironic thing is that throughout that period—and continuing—I don’t know anyone who was a more insightful and perceptive biblical archaeologist than Bill Dever. (Laughter.) He confessed to me at dinner last night that he is getting less and less interested in his EBIV [Early Bronze IV period] business [pre-biblical] and turning more and more to the Bible. I was of course delighted to hear that.

Bill Dever is one of the very few preeminent American, dare I say, biblical archaeologists. He directed for many years the ongoing excavations at Tel Gezer, which was a seminal excavation because it trained so many American archaeologists who are in the forefront today. He was for years the director of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem, now the William F. Albright School of Archaeological Research. He’s well on the way to completing the final report on the Gezer excavations. He has of course dug at many other sites—Shechem, Jebel Qa’aqir and Khirbet el-Kom. He brings a vast knowledge of inscriptions, as well as archaeological and biblical knowledge. He’s an exciting lecturer. It is a pleasure for me to introduce my friend Bill Dever.—H.S.

The reason why the debate is over is because I won. (Laughter.) There’s nothing more to say.

But it’s a pleasure to be here. I don’t think I would have come this far except for two reasons: One, for Hershel Shanks; and two, for an audience as good as I knew this would be.

When Hershel and I first discussed this symposium, we talked about the topic being the emergence of Israel. Yet, when I got the program I noticed that I was talking about “how to tell an Israelite from a Canaanite”; that’s Hershel’s editorial flair. (Laughter.) I thought immediately of the biblical tradition. You remember that when the Israelites left Egypt, they went out into the wilderness where they longed for the leeks and the onions they had enjoyed in Egypt. So I thought perhaps we could smell their breath. (Laughter.) But both the Canaanites and the Israelites have been gone for 2,500 years, so that won’t work.

The question, however, is legitimate. That is: Who were the Israelites and where did they come from—geographically, socially and ideologically? How did the Israelites differ from their Canaanite neighbors? What, if anything, was unique about ancient Israel?

I have tried to wrestle with these questions as an archaeologist. I want to say just a word, however, before we look at the newer archaeological evidence—a word about the limitations of our sources, both literary and archaeological. Today we have two brilliant expositions regarding the Bible as a source for history-writing. Both remind us of the limitations of the biblical text as a historical source. The word “history” does not even occur in the Hebrew Bible. The Bible is not history; it doesn’t pretend to be. It is literature, and a peculiar brand of theological literature at that. It is a reconstruction of the past after the past was essentially over; written, edited and put together in its present form long after the collapse of both the northern kingdom (Israel) and the southern kingdom (Judah). It therefore refracts, as well as reflects, the past. The Bible is a kind of revisionist history.

One of my theological colleagues likes to remind me that the Bible is a “minority report.” It was written by the ultra-right-wing orthodox party after the fall of Israel (the northern kingdom to the Assyrians and the southern kingdom to the Babylonians) to explain the tragedy of those events. The biblical writers are not telling it the way it was, but the way it would have been had they been in charge. (Laughter.) And that obviously gives us a rather skewed view of Israel’s past.

Until recently, the only source we had was the Bible, that is, before the birth of modern archaeology. For many people that was enough. The Bible seems very simple—if you are a bit simpleminded in your approach. I saw a bumper sticker in Tucson recently that declared, “God said it, I believe it and that settles it.” (Laughter.) But of course it doesn’t; at least it doesn’t for those who have inquiring minds.

Archaeology won’t settle the matter either. But what archaeology does do is provide a fresh perspective. Thus it solves some problems, but creates others. Archaeology produces what William Foxwell Albright, the dean of American biblical archaeology, called “external data.” If the data in the allegedly historical sources in the Hebrew Bible are somewhat limited, archaeology provides us with a never ending supply of new data that come without the editorial biases of the ancient authors and redactors. (The archaeological data are unbiased, however, only until we begin to interpret them, and then we introduce our own biases.) Potentially archaeology is a very exciting source of new information about the Bible and the biblical world.

I propose first to say a word about the two or three models of Israel’s emergence in Canaan that have already been mentioned. Then I want to show you quite a lot of archaeological data, and at the end I’ll try to give some answers.

The models were discussed by Hershel. (You will forgive us if we all call each other by our first names. We are in fact old friends. But of course that doesn’t mean that we agree about everything.) The conquest model is not subscribed to by most biblical scholars today—certainly no one in the mainstream of scholarship—and that’s been true for some time. Moreover, there isn’t a single reputable professional archaeologist in the world who espouses the conquest model in Israel, Europe or America. We don’t need to say any more about the conquest model. That’s that. (Laughter.) Not to be dogmatic about it or anything, but … (Laughter.)

Moving to the second model, the peaceful infiltration model; that seems all right until you try to chase pastoral nomads around. They don’t leave many traces in the archaeological record. You can talk about movements of people from Transjordan, going across the Jordan River into western Palestine; but there is, in fact, almost no archaeological evidence to support such movements. It’s an intriguing model—and I will suggest a version of it myself—but archaeologically it’s very hard to use. I suspect that the peaceful infiltration model rests on a kind of 19th-century nostalgia about the Bedouin, and also on ignorance about pastoral nomads and how they really operate. Many of the theories about [the emergence of] Israel as derived from pastoral nomadic origins are now suspect; they rest on faulty archaeology and faulty biblical scholarship.

If we turn to the so-called peasant revolt model, the peasants may indeed have been revolting, but that’s not the point. Again, this is a 20th-century construct. The biblical account of Israel’s origins is also a construct. So the peasant revolt model is a construct forced back upon what was already a construct. It reflects a Marxist rhetoric (and who would want to be Marxist today?). As an archaeologist, there is very little I can say about the peasant revolt model, because it rests on ideological assumptions that are very difficult to test archaeologically. What I like about it is that it stresses the indigenous origins of most early Israelites. And that does fit the archaeological evidence. But whether the early Israelites were “Yahwists” is almost impossible to say from the viewpoint of the archaeological data. (I will reflect upon that at the end of my talk.)

A fourth model was not mentioned, but it has been advanced recently by a German scholar, Volkmar Fritz, and it is one I tend to agree with. It’s called the symbiosis model. It suggests that the people I will call “proto-Israelites,” or earliest Israelites, lived for a rather long period of time alongside the Canaanites—not all the Israelites perhaps, but the majority of them. And they emerged in some way out of Late Bronze Age urban Canaanite society. That is the picture that the archaeological evidence supports better.

Let’s look at the new evidence.1 Much of this was not available even ten years ago, and a large part of it is still not published. But it represents a growing body of knowledge about which I think we can be fairly confident. I know we all stress the controversies amongst scholars, and they are very real indeed because scholars have rather healthy egos. But, in fact, there is a growing scholarly consensus on this matter. At the end I want to stress the points on which I think we probably all will agree. It’s a very different picture from the one we would have painted just ten or fifteen years ago. That is what’s exciting about archaeology. The biblical text is what it is, it cannot change; only our interpretation of it changes. But archaeology changes every day. If you invite me back next year I’ll tell you a different story; but at the moment this is the best that we have—or at least that I have.

As background to the archaeological presentation, however, let me reiterate that the traditional notion of Moses receiving the Law at Sinai is not a story that we can comment on archaeologically. I do think—as Baruch Halpern brilliantly suggests—that behind the literary tradition there must indeed be some sort of genuine historical memory; but it is unfortunately not accessible either to the text scholar or to the archaeologist. If we consider the biblical description of the Tabernacle in the wilderness, for instance, we can say nothing about its historicity. Once in awhile you hear reports that somebody has found, or is planning to find, the Ark of the Covenant. (Laughter.) A man came into my office recently and suggested that the Israelis actually know where it is. It is made of gold, and it is hidden in a cave near Bethlehem. If we could just raise money, and if I would get him a permit to dig, we could find it and make ourselves rich and famous. I suggested another place where he might go … (Laughter.) As far as I know the Ark has not been found, and I wouldn’t go looking for it. (Laughter.)

According to the biblical tradition, the people who later formed Israel entered the country through the backdoor, from the east via Jericho. Gradually they fanned out northward and southward, and in a very short time they overran the land, virtually annihilating the native population of Canaan, then apportioning all of the territories amongst the 12 tribes. Now we know at least something about many archaeological sites on both sides of the Jordan river. At Hazor in upper Galilee, where the late Yigael Yadin excavated, he believed that he had found evidence of the Israelite destruction; and, as you know, the site figures prominently in the Joshua tradition (Joshua 11:1–15). The Israelites are said to have killed Jabin the king of Hazor, “the head of all those kingdoms” (Joshua 11:10). Today, however, most archaeologists are inclined to date this destruction about 1250 B.C.E., probably too early for the Israelites, at least under Joshua.

At the site of Lachish in the south, an earlier dig dated a destruction level to about 1220 B.C.E., which would fit the Joshua account. But recently scarabs of the later Ramesside pharaohs have been found that require us to bring that destruction level down to about 1150 B.C.E. or a little later. Now, clearly it is not possible for Joshua to have led the Israelite troops against Hazor in 1250 B.C.E. and against Lachish in 1150 B.C.E.—unless he was carried out onto the battlefield on a stretcher. Neither of these destructions can be attributed with confidence to the Israelites.

Let me put the matter categorically. There is not a single destruction layer around 1200 B.C.E. that we can ascribe with certainty to the Israelites. There are some possible Israelite destructions; there are none, however, that are certain. Many sites, like Jericho and Ai (and others), were not even occupied in this period. In Transjordan, the same is true; sites like Hesbon (biblical Heshbon), Dibhan (biblical Dibon) and others that are mentioned in the biblical accounts were not occupied in the late 13th or early 12th century B.C.E., so they cannot have been destroyed. Archaeology can rarely prove something in the affirmative, but it can often prove things in the negative. It can prove that such and such did not happen, and could not have happened. That’s the case here, because the archaeological record is totally silent.

The site of Shiloh has recently been excavated by the Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein. In the biblical tradition, Shiloh was the tribal center where the Ark was kept (1 Samuel 1). But despite the most determined search, Israeli archaeologists have not been able to find anything of the Tabernacle or the shrine—or indeed anything cultic at all—from the 12th century B.C.E. And although the site was occupied earlier by the Canaanites, there is no evidence of any destruction. The site was simply taken over in the 12th century, perhaps by new peoples.

There are possibly two early Israelite shrines that do belong to the late 13th or 12th century B.C.E. The first is the Mt. Ebal installation near Shechem (modern Nablus on the West Bank), excavated by Adam Zertal.2 This structure dates mostly to the 12th century B.C.E., and it has been argued that this is the very shrine described in the accounts in Joshua 8:30–35. The date is acceptable, since an Egyptian scarab found there can be dated to the late 13th century B.C.E. But there are reasons to doubt that the Mt. Ebal installation is a shrine at all. Occupation levels produced burned bones of four kinds of animals, three of them mentioned in the Hebrew Bible in connection with descriptions of sacrificial rituals. Sheep, goats and small cattle are indeed kosher, but roe deer are not. Zertal has reconstructed the installation as a large outdoor altar upon which animal sacrifices were made, connecting it directly with the Bible. If he is correct, this is the only instance in which archaeology has ever brought to life a specific installation described in the Hebrew Bible. It would be wonderful if it were true, but it’s probably not. Most Israeli archaeologists think the Mt. Ebal installation is an isolated fort or a farmhouse. I have my own interpretation. Judging from the splendid vistas from the hilltop, the lovely breeze you get up on the mountain and the evidence of all the burned animal bones, I think it’s a picnic site where barbecues were enjoyed by families on Saturday afternoons. (Laughter.)

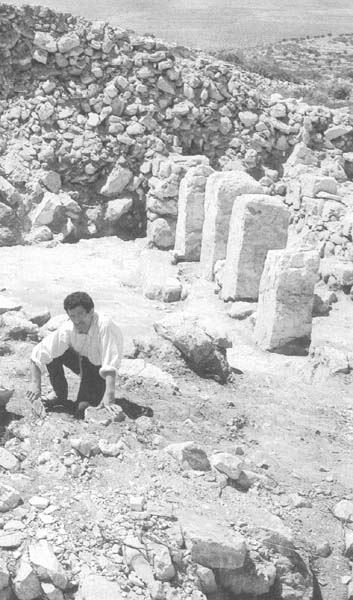

The second site, however, has a better pedigree—the so-called bull site, excavated by Amihai Mazar, one of the leading younger archaeologists in Israel today.3 It lies near biblical Dothan, north of Shechem in the hill country of Samaria. It is a small, isolated hilltop shrine with very few remains, clearly not a domestic site. It belongs to the 12th century B.C.E. to judge from the pottery fragments. The stones around it make up a kind of enclosure, or temenos wall. Mazar found a cobbled area and what the Hebrew Bible calls a massebah, or standing stone, of some sort. Here I think that the cultic interpretation is sound. The site is in the heartland of the ancient tribal territory of Ephraim, and we can probably ascribe it to Israelite settlers. The prize find from the site, found before Mazar excavated it, is a splendidly preserved bronze bull about 4 inches high (

We have almost no other evidence for religion. In short, Yahwism, with all its attendant institutions and traditions, was no doubt a product of a later period, as I think Professor McCarter will show you in the last talk. We have very little archaeological evidence in the 12th or 11th century B.C.E. of early Israelite religious beliefs or practice. That is not to say that they did not exist, but they are not very accessible to the archaeologist.

Next I want to consider the early Israelite settlement sites. It was mentioned earlier today that we know of over 200 settlement sites from the 12th and 11th centuries B.C.E. in the central hill country. In fact, we now have over 300 that we might connect with the earliest penetration of the Israelites into the hill country.

I want to look at two such sites near Jerusalem. One is Ai, to the northeast of Jerusalem, and the other is Raddana, very near Ai. Ai is, of course, a major biblical site; it figures prominently in the conquest narratives in Joshua 7–8. Yet a staunch American Southern Baptist archaeologist, Joe Callaway, excavated there for many years, quite anxious to prove the biblical tradition, but unable to come up with anything at all. The site was not even occupied in the 13th century B.C.E., so it cannot have been destroyed by the Israelites. Ai’s story is thus very much like the story of Jericho.a For the true believer, however, this kind of factual evidence is not a problem, nor any barrier to belief at all. After all, if Joshua destroyed a site that wasn’t even there, that’s a stupendous miracle—even better than the one described in the Bible. (Laughter.) So, if you want to believe the story, you’re welcome to do so, but there’s no archaeological evidence to help you.

At nearby Raddana, on the outskirts of modern Ramalleh, there was a salvage dig, also led by Callaway. It brought to light the remains of a 12th- or 11th-century B.C.E. village. The modern name is Khirbet Raddana, but many people believe that the site may be identified with ancient El-Bireh, known from biblical tradition.4

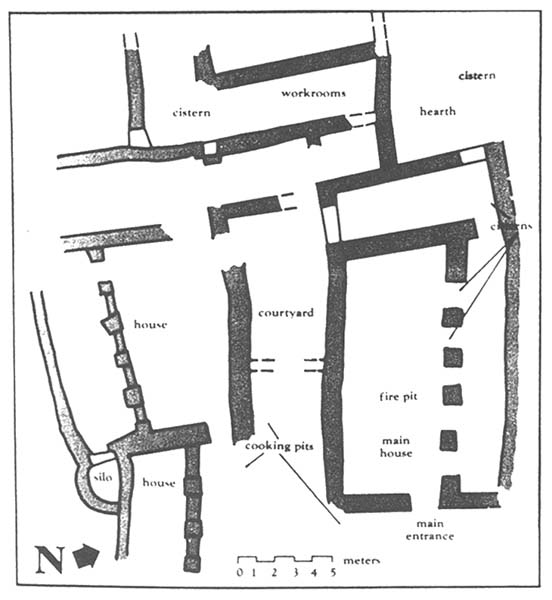

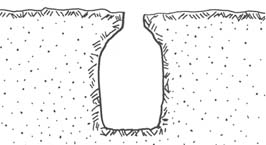

Raddana contained some nicely preserved examples of courtyard houses, or pillared courtyard houses as I prefer to call them, sometimes regarded as “early Israelite” houses. On either side of a central pillared courtyard were roofed and cobbled areas where animals were stabled. There were also large areas for storing both dry and liquid foodstuffs. Cisterns were dug under the floors of the houses and in the courtyards to provide a ready source of water. In fact, one of the reasons that the area was never effectively settled before the Iron Age was that the art of digging cisterns had not yet been perfected, and you cannot survive in the hill country in the summertime without some means of water catchment. In the central courtyard was also a firepit. On the second floor of the house, you would have had the living and sleeping quarters.

This same type of courtyard house appears again and again at each of these hill-country sites. Today the hills where these settlements were built are barren and largely abandoned. But archaeologists have found evidence of intensive terracing of the hillsides in the past. That, too, was a new technology, perfected in the late 13th and early 12th centuries B.C.E. Without that, one could not have farmed the rugged, steep hills of central Palestine. Terraces, formed by stone walls, not only get rid of the rocks covering the ground but they create a kind of stepped platform on which a donkey or an ox can pull a plow. And of course the terraces impeded runoff rain in the winter, allowing the water to percolate down. Thus terraces were a very clever device for exploiting the hill-country frontier, which had never been intensively settled before the late 13th and early 12th centuries. These terraces, one of the most important innovations of these newcomers, are a clue to their origin. (Of this, more later.)

At all of the hill-country sites, when a new house was built, it often shared a common courtyard with the older house, and even the main walls. In a brilliant article, Lawrence Stager has shown that the plan and layout of these houses, as well as that of the overall villages, could have come straight out of the pages of the Book of Judges.5

Now archaeologists are not very fond of the Book of Joshua, for reasons about which we’ve spoken. The Book of Judges, on the other hand, has the ring of truth about it, at least from what we know given the facts on the ground. In Judges, Samuel and Kings, and even in Joshua, when an Israelite identifies himself as a gever, or individual, he will say typically that he belongs to the house of X, “the house of the father” (Hebrew, bet av). As Stager has noted, that almost certainly is the compound house unit in which an extended family lived. In biblical times, as in modern times in the West Bank and elsewhere in the Middle East, when a young man marries he brings his bride to his father’s house and she joins the family. At the same time, an older couple, the grandparents, may be living there. So you tend to get an “extended family,” often three generations and as many as 20 individuals living together. Therefore, in the typical layout of these hill-country villages, what you are seeing is in fact a cluster of individual houses, the biblical bet av. The entire village—comprising perhaps a dozen such compounds—would then comprise the biblical mishpachah, not simply “family,” but “kinship group,” since everyone was related, as in Middle Eastern villages today. Stager has thus shown how in the very buildings themselves and in their furnishings we can see actual terms used in the Hebrew Bible for their socioeconomic structure. Stager’s analysis is one of the most successful articles yet in the field of biblical archaeology. Biblical archaeology may not exist, but Stager has done it brilliantly. (Laughter.)

Here in these hill-country villages, for the first time we find the early Israelites in actual archaeological context. We ought not to be chasing around Palestine looking at the great mounds and trying to dig ash layers that we can connect with destruction stories in the Bible. Instead, we ought to be looking at social and economic history, at how the new sites—both excavated and identified in surveys—may reflect the very terminology of the Hebrew Bible. That suggests that there is something behind these stories, even though they could not have been written down before the tenth century B.C.E. There is no doubt that there is some genuine historical experience reflected in these stories. (More on that later.)

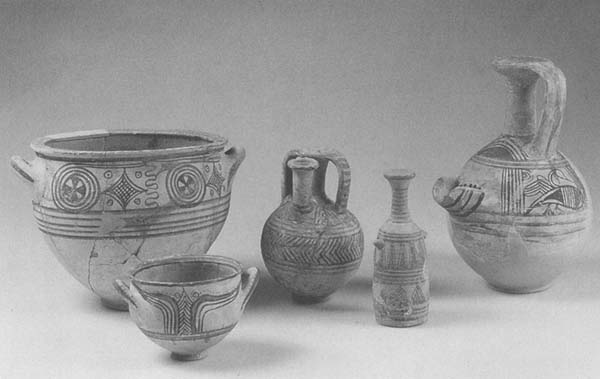

The common early Israelite pottery turns out to be nearly identical to that of the late 13th century B.C.E.; it comes right out of the Late Bronze Age urban Canaanite repertoire. As someone who has spent 30 years studying this pottery, I can tell you that, based on the pottery evidence, we would not even suspect that the people living in these hill-country sites were newcomers at all. One can’t imagine nomads sweeping in from the desert, with no architectural or ceramic tradition behind them, suddenly becoming past masters of the potter’s art in Palestine. This early Iron Age I (c. 1200 B.C.E.) pottery goes back eight or ten centuries in a long Middle–Late Bronze Age tradition. Clearly the pottery alone suggests that these newcomers to the hill country were not newcomers to Palestine. They had been living alongside the Canaanite city-states for some time, perhaps for several generations, probably for several centuries.6

By the way, I must tell you that the early Israelite pottery is pretty drab, while the Philistine painted pottery is quite sophisticated. In a wonderful twist of historical irony, we remember the Philistines as barbarians. But that is a value judgment from the Judeo-Christian perspective. I’m afraid it’s the early Israelites who were the barbarians when it comes to making pottery. Perhaps they already had their minds on spiritual things. But the pottery is terrible stuff. We know what it is, however. It comes out of the local Canaanite repertoire. There is nothing Transjordanian about it, and certainly nothing Egyptian about it. There’s nothing much new in it either, apart from the normal and even predictable ceramic developments.

In several sites we have evidence for a kind of cottage industry in metallurgy. We find a lot of copper and bronze, but not much iron, which suggests that iron was not yet an important factor, even in the early Iron Age. We don’t get many iron implements before the tenth century, at about the time of the formation of the Israelite state. In the early period, the so-called period of the Judges, we get not only copper and bronze implements but even some stone tools.

The picture we get in these early Israelite hill-country villages is of a very simple, rather impoverished, somewhat isolated culture with no great artistic or architectural tradition behind it. And yet one does not get the notion that these people were simply pastoral nomads in the process of becoming sedentarized. For instance, in these early settlements we have some indications of literacy. Archaeologists have rather large imaginations; we find one jar handle with three inscribed letters, and already “It’s a literate society.” But the point is that if somebody could write, then a lot of people could write. And we are speaking not of the old, cumbersome cuneiform script or the Egyptian hieroglyphic script. What we have is the local Canaanite alphabetic script. At Raddana a jar handle was found with an inscription on it from the late 13th or early 12th century. Restoring one missing letter, we can read, “Belonging to Ahilud.” That turns out to be a biblical name. Even though we have only hints of writing, clearly there is the beginning of a literate tradition in the earliest years of these proto-Israelite settlements.

Typically these villages are not founded on the ruins of destroyed Late Bronze Age urban Canaanite sites. They are established de novo, mostly on small, isolated hilltops. Most of the sites were undefended, with no city wall. And they were very small, not more than three or four of those big multiple-house compounds of which we spoke. The total population of most of these 300 or so villages was probably under 100; the largest that we know of cannot have been much over 300. If you combine these 300 or so sites and multiply by the numbers of houses and the area enclosed, the total population of early Israelites was perhaps about 75,000 for the entire central hill country north and south of Jerusalem, as well as the mountains of Lower Galilee. So we cannot think in terms of the inflated figures given in the biblical tradition, which are impossible. As Baruch [Halpern] will tell you, it is impossible for three million Israelites to have survived in the Negev desert, and in any case we cannot actually account for more than a population of 75,000 or so in the 12th century B.C.E. when the Israelite settlers appear in Palestine. By the 11th century, however, that population had doubled, and that is, I think, quite significant.

Now let’s look at the kind of pottery vessels Hershel said are connected with these sites—the so-called collared-rim store jars. The rim at the top is not just decorative, it’s also functional, a way of strengthening the neck of the jar. Bear in mind that these are big jars, some of them standing 3 feet high or more. You do not find them in the urban Canaanite city-states. This is perhaps the only form of new pottery that you find in the so-called Israelite settlements. Why? The answer is simple. These are ideal vessels for storage of the agricultural surpluses that you must have to survive in these villages. They are practical vessels, typical of rural areas. So the differences in pottery at Canaanite and Israelite sites may not be ethnic differences at all, and they are certainly not chronological differences. What we see is a functional difference—the difference between the pottery repertoire typical of urban sites, and that of rural sites. Here we are clearly dealing with rural sites. The point has been made by Hershel and others that these storage jars are occasionally found in earlier periods. They are also found in parts of Transjordan that probably were not claimed by early Israel. This therefore is not an Israelite-type vessel, as sometimes stated. It is simply a very practical kind of jar for the kind of settlements we have been talking about in the hill country.

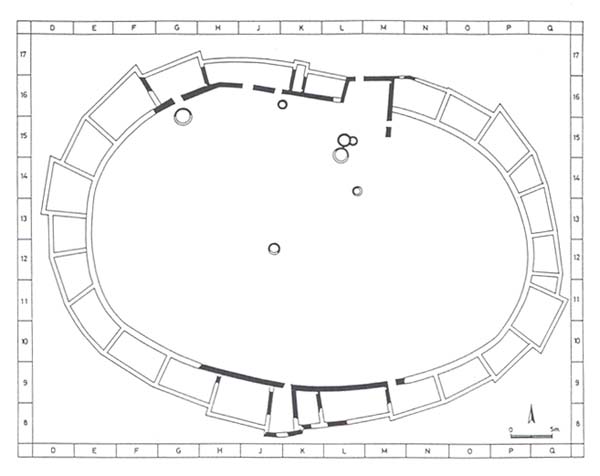

Let’s look now at the site of ‘Izbet Sartah, excavated by Israel Finkelstein.7It’s near the site of Aphek, a large Canaanite city-state that was partially destroyed a little before 1200 B.C.E. I am bold enough to suggest that this site is ancient Ebenezer. You remember the biblical story of the Ark being captured here by the Philistines (1 Samuel 4:1–18). If you know the site, you can almost see the battle. The Israelites had pressed down close to the coastal plain, but they were still living within the shadow of a large Canaanite town. This area is a buffer zone, on the natural border between the Philistine plain and the hill country where the new proto-Israelite sites were being settled. There are three strata at ‘Izbet Sartah, covering the 12th to the mid-10th century B.C.E. The lowest stratum (III), according to Finkelstein, had a circle of houses. From this, he argues that the inhabitants were pastoral nomads settling down. In other words, these houses were arranged in the same way that Bedouin sometimes arrange their tents in a circle or an oval, or in the way that wagons would be gathered in a circle when the American West was being explored and settled. That’s an interesting theory—and almost certainly wrong! Finkelstein’s own field director, Zvi Lederman, has argued that in fact there was no such circle of houses. You can see for yourself in Finkelstein’s own plan where he shows in black the areas that were actually excavated; the white areas are reconstructions by the archaeologist. Here, however, the archaeologist has ignored his own data. Finkelstein argues that the pottery from the earliest stratum can be identified as early Israelite and is totally different from the Late Bronze Age Canaanite repertoire.

Now I spent 25 years excavating at Gezer, which is only eight miles away from ‘Izbet Sartah, and I’ve handled thousands of pieces of this pottery. The pottery from ‘Izbet Sartah is identical to the pottery we found at Gezer. Now no one says that 12th-century Gezer was an Israelite site; on the contrary, it was without question a Canaanite site. It was not destroyed at the end of the Late Bronze Age, and remained a large urban site right through the Iron I period. Yet the pottery from Gezer and ‘Izbet Sartah could have been made by the same potter. There is very little difference indeed. If the people at ‘Izbet Sartah were Israelites, they were clearly using Canaanite-style pottery.

Finkelstein must know this, so he draws an analogy with modern pastoral nomads and argues that ancient pastoral nomads (his “Israelites”) absorbed Canaanite ceramic traditions over a period of time, just as Bedouin or pastoral nomads do when they settle down and become farmers. He does not argue that the newcomers came from Transjordan, much less from Egypt. He believes that they had been present in Palestine from earliest times. The Israelites, then, are simply local pastoral nomads in the process of settling down. No one denies that pastoral nomads do become sedentarized. But I would argue that these proto-Israelites for the most part were probably not pastoral nomads at all. (More on this later.)

In the next stratum at’Izbet Sartah (II), we see a real change in architecture. Here we have the same courtyard house that Hershel showed you. In this stratum, the archaeologists found well-preserved seeds and bone samples, indicating to me that these people were experienced stockbreeders. They were efficient farmers, able to produce quite large surpluses. What did they do with their surpluses? They put them in the silos and storage pits that were found all over the site, typical of all the hill-country sites. These are isolated farming villages, which don’t trade with the cities, so they must store agricultural surpluses.

Incidentally, this same kind of courtyard house continued to be used right down to the end of Israelite and Judahite history in the sixth century B.C.E. This is the Israelite-type house later on. The continuity in domestic house types is one thing that leads me to believe that these proto-Israelites were the authentic ancestors of the later Israelites of the Hebrew Bible. That is one of the reasons I use the label “Israelite” for them. The continuity of material culture from the tenth through the sixth century B.C.E. is clear. If people from places like ‘Izbet Sartah were not Israelites, then those who were citizens of the later state were not Israelites either.

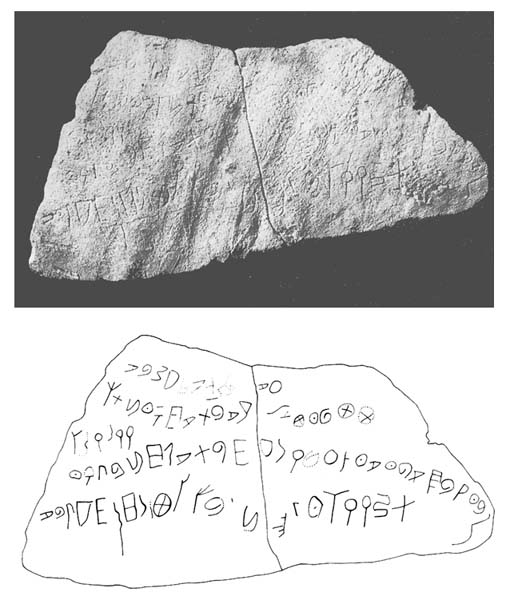

In one of the pits at ‘Izbet Sartah there was found a broken piece of pottery with an inscription scratched into it. The inscription is what is called an abecedary—an alphabet. It was probably written by a schoolboy as a practice text. It probably dates from a little before 1100 B.C.E. Obviously, if people were practicing the alphabet at that time, they could write. But there are some interesting features here. Hebrew was written later from right to left, but this fellow hadn’t quite gotten it down yet. So he wrote it from left to right. He also got a few letters out of place, and some of them have the wrong stance. Altogether, it’s a fairly crude exercise, but there’s no doubt what we have. It’s an abecedary, and the script is Canaanite. So again these early Israelites, whoever they were, were writing in a Canaanite script and probably speaking a dialect that was still a subdialect of Canaanite. Hebrew had not yet emerged as a national language and script, a development that came only with the establishment of the monarchy in the tenth century.

Many of the sites we have been talking about were abandoned in the tenth century B.C.E., toward the beginning of the monarchy. With the beginning of urbanization in ancient Israel, these rural sites were no longer viable. Many were never occupied again and thus did not build up into large mounds, and for that reason they were not even discovered until the last ten or fifteen years. They are especially valuable archaeological sites, however, because they were not built over by later people, and the material is just below the surface. Unfortunately, they are being rapidly destroyed by modern development. Furthermore, the survey work the Israelis were able to do just five years ago in the West Bank could not be done today because of political tensions. But the point is that in the physical remains of these hill-country sites there is reflected the kind of social and economic structure that comes right out of the pages of the Book of Judges. You couldn’t have a better example of biblical archaeology of the right type.

I also want to mention the site of Tel Masos from this same period, where the paleoethnozoologist analyzed the animal bones and found that more than 65 percent of them were cattle bones—not sheep and goats.8 These people were not shepherds settling down; they were experienced stockbreeders. They were not country bumpkins either, since the pottery shows trade contact with urban sites on the coast. Now Finkelstein argues that Tel Masos is not Israelite. Why? Because it doesn’t fit his model! But not even the Bible suggests that all Israelite sites were alike. Masos is different in some ways. Some of the Masos houses are larger than others, but there is no monumental architecture at all. There are no palaces, no city walls or gates, no temples.

Indeed, none have been found in any of these proto-Israelite settlements. That’s what has led some scholars like Norman Gottwald to suggest that what we have in these settlements is a kind of primitive democracy, or egalitarian society. That’s stretching it a bit, I think; no known society is completely unstratified. Nevertheless, it is clear that Masos, like the other sites, is not yet urbanized. There are no specialized “elites” in any of these sites; there is a kind of homogeneity to the material culture. You recall what is said in the Book of Judges—that “In those days there was no king in Israel, and every man did what was right in his own eyes” (Judges 21:25). (What the women did, we don’t know.) (Laughter.) Masos, along with about a half dozen of the 300 known sites, has been excavated—none with a very large exposure. What we have are intensive surface surveys over the last 15 years that have absolutely revolutionized our knowledge of Iron I settlements in the hill country.

Now let’s look at some percentages. At the end of the Late Bronze Age, in the 13th century B.C.E., in the whole of the hill country west of the Jordan we know of only about 25 sites. In Iron I, however, we have more than 250 sites. There has been an enormous increase in population that cannot be accounted for by natural birthrates alone. Vast numbers of new people were indeed moving into the hill country in the 12th century B.C.E. And the movement crested in the 11th century, when the population probably doubled. This is a fascinating demographic portrait, one of which we had no idea just 15 years ago.

What do the demographics mean? That’s the really intriguing question. Adam Zertal claims that he has identified three types of cooking pots. One flourished in the late 13th and early 12th century, right around 1200 B.C.E. Another slightly different cooking pot flourished in the mid- to late-12th century B.C.E. A third kind of cooking pot appeared in the 11th century B.C.E. No one doubts the dates of these respective cooking pots, but Zertal’s interpretation of them is suspect. He has picked up fragments of these cooking pots in a survey of 136 sites in the area allotted to the tribe of Manasseh, now in the West Bank.b. He argues, in essence, that the sites with the earliest cooking pots are on the eastern slopes of the central ridge, nearer the Jordan Valley. The later ones are found toward the central hill country and westward. For Zertal that means that there was a movement of newcomers arriving from the east and moving westward. Where did they come from in the east? Why, from Transjordan, of course.

As far as I’m concerned, Zertal’s theory cannot be demonstrated archaeologically. It’s little more than nostalgia for a biblical past that never existed. I can prove that by his own statistics. He identifies sites with only 5 to 20 percent of the earliest cooking pots as having been established only in the mid- to late-12th century or even the 11th century B.C.E. But the point is that if there are any early cooking pots there at all, then the site was established in the early 12th century. It may have been small, it may have grown later; but it has to have been established in the earliest phase of settlement. In short, there was no general movement of peoples from east to west. You have to bear in mind that Zertal is relying only on a surface survey. A surface survey means that archaeologists pick up the few fragments of pottery that they find on the surface of the ground. On a small site like Zertal’s, you might pick up sherds from ten or fifteen cooking pots. Statistics based on that kind of sample are worse than meaningless. You can’t really prove much of anything on the basis of surface surveys alone. But even Zertal’s crude statistics prove him wrong.

Another survey was conducted by Israel Finkelstein in the tribal territory of Ephraim. He reported it in his 1988 work which is now the standard treatment, The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement, a very fine book that is already revolutionizing biblical scholarship.9 That doesn’t mean, however, that Finkelstein is correct in every detail. He reports on 115 sites in his survey area. He, too, argues that the earliest sites are in the east; but instead of deriving the settlers from across the Jordan, he believes they came from western Palestine itself. However, Finkelstein does not say that they came from the Canaanite urban centers. He believes that they were local pastoral nomads who had been there for centuries, but now are simply moving up into the hill country. But I want to point out one thing. Far to the west, on the western slopes of the hill country is Finkelstein’s own site of ‘Izbet Sartah, and by his own admission it was established at the end of the 13th century B.C.E. It is one of the earliest of all the proto-Israelite sites. How then can the settlers be moving from east to west? It looks rather like they are moving from west to east.

Furthermore, even if you could show that the sites on the eastern side of the central ridge were the earliest, that too could be explained. If you were a refugee fleeing from the Canaanite city states along the coast, where would you go? To the other side of the ridge, where it’s safer. And what would you do 15 years later, when conditions had settled down a bit? You would migrate back to the west where there is better pastureland and better agricultural land.

So the above theories, based upon ceramic typology and relative statistics derived from surface surveys, can be very misleading. In the back of the minds of both these Israeli scholars—Finkelstein and Zertal—I believe there lingers a fondness for Albrecht Alt’s old explanation of Israelite origins in terms of peaceful infiltration, in this case from Transjordan. But I must stress that the Israeli archaeologists have not been able to handle the material from Jordan—for obvious reasons. There is very little archaeological material from anywhere in Jordan that would provide a background of pastoral nomadism out of which the early Israelites could have come.

Now let us review a few features quickly. The typical proto-Israelite site contains clusters of houses featuring a central courtyard, with sleeping and living areas for the family on the second floor. The flat roof would be useful for drying food stuffs and preparing food. If you visit an Arab village in the West Bank today, you can still see such houses in use. I’ve seen them all across Greece and Italy, around Syria and Turkey, down into Jordan. The point is that these ancient houses are not necessarily “Israelite” houses in themselves. They are simply very practical farmhouses of the type that begins to proliferate in the early Iron I period. The early Israelites borrowed this house plan, as they borrowed a great many other things.

What emerges from our survey of proto-Israelite sites is a kind of composite culture, in which there are both old and new features. The use of courtyard houses is new. The kind of social and economic structure that they reflect is also new. But the technology—in pottery and in metalworking—reflects a great deal of continuity with the previous societies of the Canaanite Late Bronze Age. The early Israelites are best seen as homesteaders—pioneer farmers settling the hill-country frontier of central Palestine, which had been sparsely occupied before Iron I. They were not pastoral nomads who had originally migrated all the way from Mesopotamia, as the biblical tradition describes them, moving along the edges of the Fertile Crescent up into Syria and then penetrating down into Palestine. Nor were the early Israelites like the modern Bedouin who still inhabit the area. They may not have been primarily sheepherders, although some may have been stockbreeders. For the most part, the early Israelites were agriculturalists from the fringes of Canaanite society.

It is true that the stories in Genesis seem to reflect a pastoral nomadic background. But here we are dealing with literature, not with history. There is no reason to believe that the majority of the ancestors of the Israelites had been pastoral nomads, much less barbarians sweeping in from the desert. They were displaced Canaanites. For the most part, they came from various elements of Canaanite society who decided to settle the hill-country frontier.

In a recent issue of Biblical Archaeology Review there is the relief of Ramesses II that Hershel spoke about, which some scholars believe was recarved by Merneptah.c One scene depicts the siege of Ashkelon, now being excavated by Larry Stager. Above the Egyptian inscription identifying Ashkelon there is a group of people that Frank Yurco thinks are Israelites. Merneptah, in his famous “Victory Stele,” claims to have destroyed a people called Israelites, so he must have been familiar with what they looked like. Yurco believes this scene is an actual eyewitness portrait of early Israelites. On the other hand, Anson Rainey, an Israeli scholar, believes that somewhere else on the relief is another group of people who are Israelites.d I suggest, however, that we do not have any reliable eyewitness portraits of what early Israelites looked like. And from the point of view of the archaeological remains, we know very little about their ideology or their religious beliefs and practices. But we know a lot about their social and economic structure. We know a lot about their technology. We know a lot about the demography of the regions they were settling.

Let us return now to our original questions: Who were the Israelites? Where did they come from? And how were they different from the Canaanites?

In my judgment, on the basis of both the archaeological evidence and an understanding of the biblical text, particularly the tradition preserved in the Book of Judges, the early Israelites were a motley lot—urban refugees, people from the countryside, what we might call “social bandits,” brigands of various kinds, malcontents, dropouts from society. They may have been social revolutionaries, as some scholars hold, imbued with Yahwistic fervor, although that’s not traceable archaeologically. They may have had some notion of religious reforms of one sort or another. There does appear to be a kind of primitive democracy reflected in the settlements and the remains of their material culture.

Perhaps this group of people included some pastoral nomads, even some from Transjordan. I’m even willing to grant that a small nucleus of people who became Israelites had originally been in Egypt, as Baruch Halpern suggests in his analysis of the literary tradition. (This is the only way that you can save the literary tradition; otherwise you will have to jettison it completely.) Thus, it is quite possible that there were some newcomers in this mixture of peoples, who were, however, mostly indigenous Canaanites. And all of them were indeed newcomers to the hill country. They were settling down there for the first time; that is what is new. What is old, however, is their technology, particularly their pottery, their language and their script, factors that indicate a rather strong cultural continuity, despite a new ethnic consciousness.

In short, if you had been walking in the countryside of central Palestine, especially in the hill country, in the 12th or 11th century B.C.E. and had met several people, you could probably not have distinguished Israelites from Canaanites or Canaanites from Philistines. They probably looked alike and dressed alike and spoke alike. But the kinds of things that now enable us to talk about ethnicity will have disappeared from the archaeological record.

So how do we know the people in question were Israelites? My solution is a rather simple one. First of all, we have not only the biblical tradition that calls them Israelites, but we also have the Merneptah Stele that proves beyond any shadow of a doubt that there was a distinct ethnic group in Palestine before 1200, one that not only called itself “Israelite” but was known to the Egyptians as “Israelite.” That need not be the same as later biblical Israel; but the label “Israelite,” which I want to apply to these early Iron I sites, is not one that I invented. It’s attested in the literary tradition, both biblical and non-biblical.

Another point is this: In the tenth century B.C.E. and later, at the time of the Israelite monarchy—and no one doubts the existence of that—you have the continuation of the material culture at which we have been looking. All you have to do is push that assemblage, as archaeologists call it, back into the 11th and 12th century. If it was Israelite in the 10th century B.C.E., then it was Israelite in the 12th century B.C.E. For these reasons, I use the term “Israelite” for the early Iron I hill-country settlements, although I use it in quotes, and I prefer to speak of “proto-Israelite” settlements.

The model I’ve advanced here is useful, probably the best model we have at the moment. But remember what a model is: a hypothesis, meant to be proven or disproven. Perhaps we will see it all differently in another ten or fifteen years.

Suppose that we were to excavate a site we presumed to be Israelite, identified by a modern Arabic name that was the same as the biblical name. Suppose that we found a destruction layer, a nice big, healthy destruction layer—thick ashes, smashed pottery, everybody killed, just what archaeologists like. And suppose that above that stratum we found a new style of pottery, new burial customs and a new material culture. And suppose that we get really lucky and find a monumental stele that says “I, Joshua ben-Nun, on this Tuesday morning, April (laughter) the 9th, in the year 1207 B.C.E., destroyed this site in the name of Yahweh, the God of Israel.” You might say that such a discovery would be archaeological proof of the historicity of the biblical tradition. That’s exactly what an earlier generation thought. But it is not. After all, what is the claim of the Hebrew Bible? Not that Israel took Canaan, but that Yahweh gave Canaan to the people of Israel. That’s a theological assertion, which cannot be proven by archaeology—and it can’t be disproven, either. The point is that centuries later, as the writers and editors of the Hebrew Bible looked back upon their own experience, they could not understand how they had gotten where they were. They could not explain their own origins. To them it seemed a miracle. And who are we, their spiritual heirs, to disagree?10

Questions & Answers

Question: Sir, as I understand it, pottery found in Avaris in Egypt is a Canaanite type. If that’s so, isn’t it possible that the people did come from the Goshen area and had a tradition of Canaanite-style pottery.

William G. Dever: Yes, Hershel mentioned that earlier. But the point is that the Canaanite pottery in question is the pottery of the last phase of the Middle Bronze Age—from about 1650 to about 1550 B.C.E.—centuries before the emergence of Israel. It can have no possible connection. I have argued vociferously with Manfred Bietak, the excavator of the site, showing that his material is indeed Canaanite, which means—exactly as Hershel said—that large numbers of Asiatics were penetrating into the eastern Delta in the first half of the second millennium B.C.E. Baruch [Halpern] touches on that too. That may indeed provide a historical nucleus out of which the later biblical stories came.

I would like to be the first to say that I give full assent to everything Baruch says. It is highly likely, I think, that among the principal editors of the biblical tradition were people who belonged to the so-called house of Joseph, parts of the tribes of Benjamin, Judah and Manasseh. And, indeed, among them there probably were people who had been in Egypt who, in one way or another, thought that they had miraculously escaped. What they have done, however, is to impose their own experience upon many other peoples who came rather from Canaan. Israel was a confederation of peoples. The Bible hints of that already. Remember that passage in Ezekiel: “You are of the land of Canaan; your father was an Amorite and your mother a Hittite” (Ezekiel 16:3). The Israelites remembered their own ancestry. What they did later, in the literary tradition, was to neaten it up a bit, to make it all-inclusive, “all Israel.” The cultural unity implied in the biblical narrative was probably not present in actual fact in the 13th and 12th centuries B.C.E., but only developed later. I think that the unifying factor probably was Yahwism, but that we can’t trace archaeologically. So, yes, there are roots. As for the Late Bronze Age Canaanite storage jars found in Egypt, which Hershel mentioned, these are trade items; they are shown being off-loaded from Canaanite ships by Egyptians. This has nothing to do with ethnic movements. All this is to say that yes, some of the ancestors of Israel may have been in Egypt, but it’s quite clear now that by no means all of them were.

Q: You spoke of the majority of the Israelites coming from a Canaanite background and moving up into the hill country, a rather difficult terrain on which to subsist. Where did they come from literally, and why did they go there?

Dever: I don’t think we can be too precise about that. I have suggested they came both from the urban Canaanite centers of the Late Bronze Age as well as from the countryside. I don’t believe you can build agricultural terraces overnight; I don’t believe you can learn to breed cattle overnight. I think these newcomers were experienced farmers for the most part, although not necessarily Norman Gottwald’s “peasant farmers.” The term “peasant” is from later periods and should not be applied to early Israel. These folk were experienced farmers and stockbreeders, probably not peasants but freeholders. They were not foreigners at all; they were displaced Canaanites. We can’t locate them more precisely than that.

Q: Well, if they were urban Canaanites, where did they get their farming experience?

Dever: As I’ve said, I don’t think all of them were, or even most of them. Among them there were possibly refugees from the urban centers who might already have been in the countryside for a generation or more. From the Amarna letters, we know that the Canaanite city states were collapsing as early as 1400 B.C.E. There was a mass exodus from these Canaanite cities, so there was already present a large rural population, which was always in flux. The hill country provided the perfect retreat for them. It is precisely what modern Christian and other dissident groups have done in southern Lebanon today, they have retreated to the hill country. The situation is very similar.

Q: As a collateral question to what has just been asked, are you saying that the major social, economic and political unit remained the mishpachah, the family?

Dever: Yes. Archaeologically we are able to comment on social history; that’s what seems most amenable to us. As an archaeologist, I would describe early Israel as an agrarian social movement, probably with a strong reformist base, as such movements have often had in history. Beyond that, I don’t think the archaeologist can go. But it is the agrarian character that fits perfectly with both Joshua and Judges, as well as Samuel 1 and 2.

Q: Would some of them—since they came from disparate backgrounds, technologically speaking—would some of them perhaps have been experts in metalworking?

Dever: Some of them, perhaps, knew iron working well, just as they knew primitive pottery making. But it is all local. In other words, the basic socioeconomic structure is the family, producing its own economic necessities. I think that later Israelite society and religion grew out of that. And that is absolutely in the spirit of the biblical traditions.

Q: You described two villages close by each other. One was clearly a Canaanite site in which there was a certain kind of pottery, and then nearby was an Israelite site. How do we know that the pottery of the type you were speaking of in the latter was not a trade item?

Dever: Because it’s all the pottery there is at the site; you’d have to argue that all the pottery was traded into the site, not just a few items. The total ceramic repertoire at both sites is indeed similar, but the difference is this. At Ebenezer (‘Izbet Sartah, if it is indeed Israelite Ebenezer), you have a completely different house-form from Canaanite Aphek, you have a completely different economy and social structure. At Aphek you have the large palace of a ruler, with cuneiform documents, reflecting a literate urban society. Ebenezer is a small farming village a few miles away. And although the pottery is the same, I think that the people are very different—in other words, a different ethnic group. I didn’t define “ethnicity,” but you all know what it is. When a people, a social group, begin to think of themselves as being different, they are. And that’s exactly what early Israel was—an ethnic group, which, already in the 12th century, had a self conscious identity, a sense of “peoplehood.” The picture of that identity changed and grew in the Hebrew Bible, but already in the 12th century B.C.E., Israelites knew that they were different. That doesn’t mean, however, that the early Israelites were unique; they were different, and they knew themselves to be different.

To conclude, you don’t just look at a single pot; you look at the whole pottery repertoire. And you don’t look only at the pottery; you look at the whole site. You have to compare things in that way.

Q: What made them different?

Dever: As I say, according to the biblical tradition, it was not only their religious faith but their moral superiority. I can’t comment on that as an archaeologist. I do suspect that religion was a powerful factor in social change, as it often has been. But here we are dependent on our textual scholars. Happily, the last talk today is to be presented by Kyle McCarter, who’s given a lot of thought to that. He will talk about Yahwism and how it emerged. I’m simply trying to be honest about the limitations of the archaeological evidence. We can’t really deal with political or religious history very well. We can, however, deal with social and economic history. And we can take a label from the text and affix it to a material culture and say this looks to us as though it may be “Israelite.” But final proof is always lacking—which is what keeps us in business and allows me to travel to visit with you. (Laughter.) Thank you.

Responses

Because Professor Dever directly commented on the views of three other major scholars—Israel Finkelstein, Norman Gottwald and Adam Zertal—who have played a significant part in the debates on the emergence of Israel, we have given them an opportunity to respond to Professor Dever in this printed version of the symposium. Following their remarks is Professor Dever’s reply to these additional responses.

Before engaging in yet another duel with Bill Dever, this time on his recent theory on the origin of the “proto-Israelites,” I wish to say I share Hershel Shanks’ esteem for his scholarship. There is no doubt that Dever is one of the leading biblical archaeologists on the scene today; my debates with him—on the fortifications of Gezer, on the nature of the Intermediate Bronze Age and now on the rise of early Israel—have always been accompanied by a deep appreciation for his field work and for his theoretical contributions to the field of Palestinian archaeology.

In his talk, Dever adopts a Gottwaldian approach to the emergence of early Israel. His theory rests on three pillars, all suggested as early as the 1970s by supporters of Gottwald’s social-revolution hypothesis. These three “pillars” of conventional wisdom were all discredited in the 1980s in light of new data that have been revealed in comprehensive field work—surveys and excavations—in the central hill country of Israel. This brief response to Dever’s discussion begins with an examination of the three pillars supporting his theory.

(Shaky) Pillar One: The emergence of Israel in the highlands of Canaan was made possible by two technological innovations. Dever adheres to Albright’s half-century old theory,11 that the Iron I wave of settlement in the highlands was a result of a new skill—that of hewing water cisterns: “In fact, one of the reasons that the area was never effectively settled before the Iron Age was that the art of digging cisterns had not yet been perfected.” There are three grave flaws in this hypothesis:

A. The central hill country of Canaan was already quite densely settled in the Early Bronze Age and again in the Middle Bronze Age.12

B. The results of the 1968 survey have proven beyond any doubt that the knowledge of hewing water cisterns had already been mastered in the Middle Bronze Age,13 and most probably even earlier, in the Early Bronze Age. Scores of Early and Middle Bronze sites are located in hilly areas devoid of any permanent water sources.14 The hewing of plastered water cisterns was therefore an outcome of the penetration into these “dry” areas, rather than the factor that opened the way to the expansion into these geographical niches.

C. Many of the Iron I highlands sites are devoid of such water cisterns; apparently, their inhabitants brought water from distant springs and stored it in the typical large Iron I pithoi.15

Dever adds that terracing, too, “was a new technology, perfected in the late 13th and early 12th centuries B.C.E.,” and that it enabled the proto-Israelites (Dever’s excellent name for the early Iron I settlers in the highlands of Canaan) to exploit the highlands frontier. He further argues that the sophisticated skill of building terraces indicates that their builders came from a rural, sedentary background. This theory was also proposed long ago, when the knowledge of the settlement history of the highlands was still in its infancy.16 It is now clear that the Iron I settlement process began in areas of the hill country that did not require the construction of terraces—the desert fringe, the intermontane valleys of the central range, and flat areas, such as the Bethel plateau. Moreover, the Middle Bronze activity on the western slopes of the highlands—where cultivation without terracing is almost impossible—seems to indicate that terrace construction was already carried out at that time. There is good reason to believe that terracing was practiced even before, in the Early Bronze Age, with the first widespread cultivation of olives and grapevines in the hill country.17 Terracing was therefore an outcome of the demographic expansion into the rugged parts of the hill country and the beginning of highlands horticulture, rather than an innovation that made this expansion possible. The terraces indicate that their builders practiced horticulture; they tell us nothing about the origin of these people.

(Shaky) Pillar Two: There is a clear continuity in the material culture between the Late Bronze Age sites of the lowlands and the Iron I sites of the highlands; this proves, according to Dever, that the inhabitants of the latter originated from the sedentary population of the former. According to Dever, “the common early Israelite pottery turns out to be nearly identical to that of the late 13th century B.C.E.; it comes right out of the Late Bronze Age urban Canaanite repertoire.”18 Indeed, certain Iron I highlands types of pottery do resemble Late Bronze vessels. But at the same time, there are some fundamental differences; the Iron I highlands assemblages are poor and limited compared to the rich, decorated and varied assemblages of the Late Bronze Age.

In any case, the essential question is whether we can learn about the origin of the makers/users from the ceramic repertoire. Ceramic traditions are influenced by the environment of settlements, by the socioeconomic conditions of the makers/users, by earlier traditions, by conventions of nearby regions and, in certain cases of migration, by customs brought by the settlers from their original homeland. In the case of the highlands of Canaan in Iron I, signs of continuity of Late Bronze traditions show no more than certain influence from Iron I lowlands sites, which still practiced at that time the pottery traditions of the previous period; signs of discontinuity reflect the fact that the highlands people lived in small isolated, rural, almost autarchic, communities. Both the continuity and the discontinuity indicate environmental and socioeconomic conditions rather than direct roots in the Late Bronze lowlands.

The same holds true for the architectural traditions of the early Iron Age highlands sites, especially the four-room house. Dever’s claim that the early Israelites “borrowed this house plan, as they borrowed a great many other things” is disproved by the fact that intensive research of over a century, in dozens of Late Bronze sites, has failed to reveal even one Late Bronze prototype of this house plan.19 The four-room houses were gradually developed in Iron I in order to adapt to the hilly environment of the settlers.

The material culture of the Iron I highlands sites cannot provide the desired answer to the riddle of the origin of the proto-Israelites. We should turn therefore to the other branch of modern archaeology—the study of the dispersal of human communities over the landscape, that is, settlement patterns.

(Shaky) Pillar Three: The wave of settlement in Iron I was the first significant settlement process in the history of the hill country. Dever states that the central hill country of Palestine “had been sparsely occupied before Iron I,” a statement which leads him to the conclusion that the Iron I people came from the lowlands. This assertion, too, fits the status of archaeological research in the 1960s. Recent surveys have shown that the region was intensively occupied twice before Iron I—in the Early Bronze Age, when dozens of sites were established in the area between the Jezreel and the Beer-Sheva valleys, and in the Middle Bronze Age, when about 250 sites were founded in this region.20 These data are crucial for understanding the settlement process under discussion here.

As for the later history of the proto-Israelite sites, Dever claims that most of them “were abandoned in the tenth century B.C.E.” That may be true for some of the excavated Iron I sites such as ‘Izbet Sartah, Giloh, Khirbet Raddana and Ai—in fact, most of these sites were chosen for excavation for that very reason: the Iron I remains were easy to uncover—but the majority of Iron I sites in the hill country continued to be occupied throughout the Iron Age. In southern Samaria, for instance, only 22 of the 115 Iron I sites (19 percent) were deserted in Iron II, 76 of the sites even expanded in Iron II.

Dever also takes issue with the results of my excavations at ‘Izbet Sartah, a site located in the foothills of Samaria, overlooking the coastal plain near Aphek. Dever does not accept my reconstruction of the layout of stratum III at this key site as an oval settlement with a large central courtyard surrounded by a row of broadrooms, on the ground that the remains are too scanty. He further argues that the ‘Izbet Sartah finds indicate that the Iron I highlands people came from lowlands urban or rural background. A close look at the plan of the site reveals that almost 40 percent of the total length of its peripheral wall was uncovered, together with the remains of seven of the adjacent broadrooms. That is enough for a reasonable reconstruction. The reconstruction of stratum III is based on a comparison with other Iron Age sites in different parts of the country, a method that Dever embraced in his recent illuminating review of my ‘Izbet Sartah report and my Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement.21

Dever then opposes my theory on the origin of the people of ‘Izbet Sartah: “How then can the settlers be moving from east to west? It looks rather like they are moving from west to east.” In all my work on early Israel, I emphasized that in the early stages of Iron I the settlers opted for ecological niches that were convenient for a subsistence economy based on dry farming and animal husbandry. Data on the economy of premodern Arab villages in the vicinity of ‘Izbet Sartah indicate exactly this kind of subsistence. Unlike Adam Zertal, I have never tried to portray a direct east-west movement of the proto-Israelites; rather, I described it as a gradual shift from regions adapted for a grain-growing-herding economy (desert fringe, eastern flank of the central range of the central hill country, foothills, etc.) to niches convenient mainly for horticulture (the western slopes of the central range). This geographical and economic expansion also sheds light on the political development of the early Israelites.22

We are able to trace these demographic developments by a meticulous study of the pottery collected in dozens of survey sites. But surprisingly, Dever dismisses the importance of quantitative analysis of survey assemblages, claiming that in a small Iron I site in the highlands “you might pick up sherds from ten or fifteen cooking pots. Statistics based on that kind of sample are worse than meaningless.” However, in the study of survey pottery, it is not the single site with 10 or 15 sherds that is important, but the overall picture of a region. Thus, a quantitative analysis based on over 100 sites, each yielding 10 or 15 sherds, is no less reliable than most statistics provided by careful excavations.

To sum up, old-fashioned, cisterns-terraces-pots solutions to the problem of the emergence of early Israel leave us in the same miserable spot where we stood two decades ago. They should be replaced by the following observations, which are based on new data revealed in the comprehensive surveys conducted in the hill country in recent years:

1. The emergence of Israel in Canaan must be viewed with a long perspective.23 Investigation of any complex settlement process should start several centuries before it commenced and end after it ripened. Applying this rule to the problem of the origin of the Israelites, one must start with the settlement developments in the Middle Bronze Age and end with the demographic processes of Iron II.

2. The settlement process in the highlands in Iron I was a third peak in a cyclic history of alternative demographic expansion and decay. These developments included three waves of settlement (in the Early Bronze I, Middle Bronze IIB–C and Iron A, with two periods of severe settlement crisis between them (Intermediate Bronze Age and Late Bronze Age).24 The settlement of the proto-Israelites was therefore one phase in a two-millennia-long process that came to an end with the rise of the national territorial states of Iron II. Any attempt to understand the emergence of early Israel without taking into consideration this background is doomed to failure.

3. The geographical dichotomy between highlands and lowlands in the southern Levant, as well as in other parts of the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean world, led to the formation of different social, economic and political structures. Therefore, some of the characteristics of the Iron I hill country of Canaan can be more usefully compared to distant hilly regions, rather than to the nearby lowlands.25

4. In the highlands of Canaan, as in other frontier regions in the southern Levant, there was always a significant pastoral element in the population. The share of the pastoral groups grew in times of settlement crisis and shrank in periods of stability and prosperity.26 The emergence of Israel was part of these demographic oscillations: The breakdown of the political system of the Middle Bronze Age led to the nomadization of a significant part of the population of the highlands frontier; in the Late Bronze Age these pastoral groups lived in a close symbiotic relationship with the remaining urban centers. Another crisis in the urban system occurred at the end of the Late Bronze and demolished these symbiotic relations, forcing the pastoralists to settle down. Other groups—local and foreign, pastoral and sedentary—also settled in the hill country in the course of the upheaval in the Late Bronze-Iron I transition, including certain elements from the collapsing sedentary system in the lowlands. These diverse groups crystallized in a slow and gradual process into the early Israelite monarchy of the tenth century B.C.E.

Dever does not take into consideration these observations. Instead, he follows the biblical tradition, seeing the emergence of Israel as a unique phenomenon—an “event,” rather than a phase, in a long, cyclic historical process.

As usual, I am impressed by William Dever’s balanced and temperate reading of the archaeological data and I agree with virtually all of his generalizing characterizations of early Israel, particularly his judgment that it was an agrarian social movement lacking specialized elites. I am also in accord with his call for a more attentive and nuanced study of its social and economic history. Like Lawrence Stager’s article on the Israelite family, which he cites with praise, Dever’s own discussion is rich in contributions toward just such a social and economic history.

By contrast, Dever is theoretically “adrift at sea” when he tries to attach a working model of society to the archaeological data he has assessed. Unfortunately, Dever fails to see that an agrarian social revolutionary reading of Israel’s communitarian society makes far more comprehensive sense of his detailed description of early Israel than does the “symbiosis” construct he puts forth.

In my view, symbiosis is not really a comprehensive model at all; instead, it is a valuable but restricted hypothesis asserting that Israel slowly gained ground in the highlands without breaking decisively with all, or even most, aspects of Canaanite culture. Symbiosis tells us something about Israel’s point of departure, chiefly that Israel was not a de novo creation, but it does not tell us much about the socioeconomic lineaments of emerging Israel, particularly the junctures at which Israel began to distinguish itself from the rest of Canaan. Symbiosis is therefore one of the preconditions for, even one of the first steps in, developing a far more comprehensive and multidimensional model of Israel as a social transformation within Canaan, achieved by Canaanites on the way to becoming an autonomous society and culture.

A major reason for Dever’s lapse at the point of developing a covering theory is that he seems uninformed about recent developments in social-critical theory concerning early Israel. For example, he apparently does not realize that since 1985 I have abandoned the terms “peasant revolt” and “egalitarian society” as imprecise and misleading explanatory categories for early Israel, or that I have replaced them with constructs of “agrarian social revolution” and “communitarian mode of production.” The result is that Dever’s comments on my modeling of early Israel have as much currency as would an attempt on my part to assess Dever’s archaeological interpretations based exclusively on his work prior to 1985. Also, although I realize that the format of the symposium does not call for documentation, I see no sign that Dever recognizes the pertinence of the work of many other contributors to early Israelite social history, among whom I would name Robert B. Coote and Keith Whitelam,27 James W. Flanagan,28 Neils P. Lemche29 and William H. Stiebing, Jr.,30 for starters.

Dever thus leaves us with two feeble alternatives: either an outmoded, pre-1985 peasant revolt theory that all social theorists of early Israel have advanced beyond, or a symbiosis theory that explains only a small part of what needs to be explained.

What do I mean by conceiving of early Israel as a communitarian social revolution? I mean that Israelites became free agrarians who enjoyed the full use of their own surpluses, unlike other Canaanite cultivators who were constantly endangered by taxation and debt payments. “Public services” promised and erratically delivered by city-states, such as defense and administration of justice, were provided in Israel by intertribal networking. Meanwhile, the cult of Yahweh, with its attendant religious ideology, expressed the interests and values of the communitarian movement.

This major shift in the mode of production prevailed over a considerable territory in the Canaanite highlands for some two centuries.

But does this historically modest achievement really deserve to be called a social revolution? My considered judgment is that it does. But it is critical to acknowledge that how one reasons for or against that conclusion is closely connected with the disputed issue of “social intentionality” in early Israel. What were these people up to? How did the Israelite communitarian mode of production happen to emerge? Was it preplanned? Was it consciously shaped in midcourse? Was it an inhibiting cultural legacy? Was it an unwanted historical accident?

As I see it, three basic viewpoints have been suggested on this issue. Some believe that Israel’s communitarian mode of production was a carryover from its earlier lifestyle of pastoral nomadism, and was thus a wholly predictable cultural inheritance which Israel outgrew as it settled down. Others believe that communitarianism developed in Canaan because of a breakdown of the city-states so massive that rural communities were thrown on their own resources and learned to cooperate to survive, and thus reluctantly adopted a lesser-of-evils strategy for coping with an undesired happenstance. Still others, myself among them, believe that this communitarianism—however much aided by city-state decline—was an insurgent movement recruited among a coalition of peasants, pastoralists, mercenaries, bandits and disaffected state and temple functionaries who simultaneously worked to oppose city-state control over them and to develop a countersociety, and the result was therefore, in substantial measure, “intended” by them. This is not to say that Israelites were in agreement on all aspects of social organization, or that they all adhered to the agreements and institutions they worked out, or that they were able to foresee the consequences of what they were doing. It does mean that by and large they wanted to be free of state sovereignty and, in its place, to develop loosely coordinated self-rule, despite all the problems that decentralization created for them.

Dever and I are in agreement that Israel’s communitarianism was not the legacy of pastoral nomadism, but I do not see that Dever’s inclination toward symbiosis yields us anything more than a formal restatement of what is evident about the cultural and technological overlap between Canaan and Israel.