En-Gedi

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

The latest excavations at En-Gedi were conducted during seven consecutive seasons from 1996 to 2002, under the direction of Y. Hirschfeld on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The excavations focused on seven areas in the En-Gedi oasis: the Roman-Byzantine village (areas A, C, D), the Roman bathhouse (area E),

EXCAVATION RESULTS

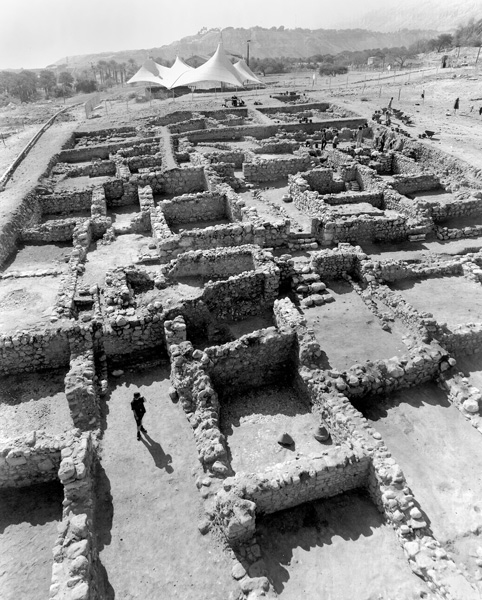

THE ROMAN-BYZANTINE VILLAGE (AREAS A, C, D). During the course of the excavations a large area of about 1 a., one-tenth of the total area of En-Gedi, was uncovered north of the synagogue. This area was described by Eusebius in the fourth century CE as a large Jewish village where the balsam plant (opobalsamum) was cultivated. The village was densely built up with houses in very close proximity to each other; building remains were encountered wherever an excavation area was opened. Four main settlement strata were distinguished in the village, dating to the Early Roman (stratum IV), the Late Roman and Byzantine (strata III–II), and the Mameluke periods (stratum I).

The Early Roman Period (Stratum IV). The remains of Early Roman period consist of pottery, including painted Nabatean bowls; coins of Alexander Jannaeus, Herod, Agrippa I, and the procurators; and a rich assemblage of vessels of Jerusalem stone, pointing to the close ties En-Gedi enjoyed with that city. Few architectural remains were found from this period; they were situated in the southern half of the excavated area (but see below the description of remains from this period excavated by G. Hadas in an area west of the synagogue). In the northern half were uncovered the remains of an irrigation channel, evidence that in the Early Roman period this area of the oasis was outside the limits of the village and used for cultivating crops. In addition to the walls of houses from the Early Roman period, a well-preserved, square-shaped mikveh was found (1.7 by 1.7 m, 1.7 m deep). A stone-built and plastered water channel conveyed water to the mikveh from the west, probably from the spring of En-Gedi. The sides of the mikveh and its four steps were plastered with a grayish hydraulic plaster characteristic of the Herodian period. At the bottom of the mikveh was a large group of pottery and stone vessels covered with a layer of debris containing evidence of a fierce conflagration. This may have been the result of the massacre of the inhabitants of En-Gedi by the Sicarii from Masada in the spring of 68 CE, as told by Josephus (War IV, 402).

The finds from the period between the First and Second Jewish Revolts against Rome consisted mainly of coins: 33 Roman provincial coins and 26 imperial coins. These coins represent the revival of the settlement at En-Gedi in this period, as is evidenced in the

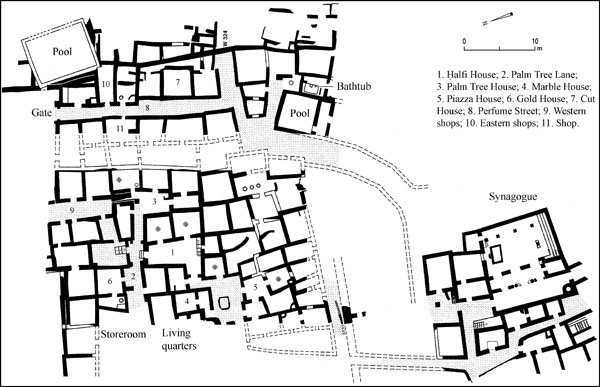

The Late Roman and Byzantine Periods (Strata III–II). The impressive remains from the Late Roman and Byzantine periods attest to the village’s prosperity during this time, from the end of the second to the end of the sixth century CE. Based on the hundreds of coins and the large and rich assemblage of pottery and glassware, the site appears to have been continuously occupied until its destruction in a fierce conflagration and its abandonment in the second half of the sixth century. In addition to houses, the building remains also include streets and lanes, shops and shop buildings, perhaps a bathhouse, and a series of storerooms. The storerooms and shop buildings are situated in the northern part of the excavations, far from the synagogue, while the houses and the bathhouse are in the south, closer to the synagogue. Assuming that the area of the excavations represents the general layout of the village, it seems that the village was divided into three concentric circles: an inner circle around the synagogue for the village’s social and religious needs, a middle circle of residential buildings, and an outer circle of commerce, light industry, and storage. Since the community at En-Gedi could not itself produce substantial amounts of wheat, oil, and wine, they had to be imported in large quantities. This need called for rules of communal organization, as reflected in an inscription in the synagogue.

The plans of six houses could be ascertained. The largest and most impressive has been called the

The second house adjoining the east side of the

The third house, nicknamed the Marble House, adjoins the western side of the

The fifth house with a clear plan is located north of Palm Tree Lane. Referred to as the Gold House, it consists of a front courtyard and a small room on its west side. In the threshold of the doorway between the courtyard and the room were found 15 gold solidi and half-solidus coins dated to the fifth–sixth centuries CE. In a corner of the small room was a baking oven of the type common at En-Gedi: a round tabun (0.7 m in diameter) with a truncated top. A bed of coals was prepared and the cooking pot was inserted and removed through the open top of the tabun. A stone with two depressions in front of the tabun may have served as a knee rest while cooking.

The sixth house is situated in the eastern part of the excavated area. It is called the Cut House because in a later period, around 400 CE, it was cut by a massive north–south wall (W324) that may have been built to protect the village from flooding by the Dead Sea. (There is evidence that by the early Byzantine period the level of the sea had risen and perhaps reached the level of the village.) The Cut House consists of three rooms in a row along the street, referred to as the Perfume Street. The street is long (35 m) and ran in a general north–south direction, beginning at the northern end of the village and continuing southward and turning southwest towards the synagogue. The Cut House was approached from the street through a narrow path alongside the massive wall. In the northernmost of the three rooms was a well-preserved industrial installation that consisted of a stone-built basin and a storage jar set into the floor. A third, similar installation was found in a shop attached to the house on the north side. These installations attest that cottage industries producing perfume existed in En-Gedi during this period.

A row of storerooms and shop buildings are situated in the northern part of the excavated area. The storerooms consist of five rooms built in a row in an east–west direction with no courtyards or other rooms attached to them. Since no building remains were uncovered north of these storerooms, they probably formed the village’s northern border. The average size of the rooms is 24 sq m. The eastern storeroom was entered through the rear doorway of the adjoining shop, from which a passage led to the second storeroom. The entrances to the other storerooms were not found.

Two shop buildings were uncovered in the excavation, one with four shops in the western part of the excavation and the other with three shops in the eastern part. The western building is situated on the northern extremity of the village; the four shops opened onto a relatively short street (15 m long). The floor of the shops is formed of a hardened layer of small pebbles covered with a layer of plaster. One of the shops contained a large millstone of the donkey mill type, suggesting that it may have been a bakery. In another shop, traces of high quality hydraulic plaster were found on the walls.

The building with the three shops is located east of Perfume Street. The shops share a common front. No signs of a dwelling, courtyards, or steps leading to a second story were found in the rooms, and it was therefore probably a commercial building that may have belonged to a local entrepreneur who rented out shops, or to a farmer who sold his agricultural produce there. In the southernmost of the three shops was an industrial installation of the type described above, as in the Cut House. Opposite this building on the other side of the street is another shop, with a cooking stove next to the entrance.

At the northern entrance to Perfume Street are the remains of a gate, constructed for reasons of halakhah, specifically related to the carrying of objects on Shabbat. The gate, 2.5 m wide, faces north towards the oasis’s agricultural area and was built at the entrance to the street, even though the village was not walled. The gate has two stone jambs but no grooves into which doors could have been inserted for locking. The jambs, together with the wooden lintel (not preserved), were apparently intended to represent a symbolic gate, which from a halakhic standpoint, transformed the village from public property to private property (Mishnah ‘Eruv. 1.2), thereby permitting the carrying of objects from one house to another within the village on Shabbat and holidays. North of the gate is a square and to its east, at a lower level, is a large irrigation pool with a capacity of about 150 cu m.

In the southern part of the excavated area, about 30 m northeast of the synagogue, are the remains of a structure with washing facilities. It contains a large pool (6.5 by 6.5 m) with a capacity of 127 cu m. Adjoining the pool, on the other side of a wall, is a bathtub (2.6 by 1.5 m) in a room entered from a corridor to the south. The entrance to the pool was also from the south, through the same corridor, but this section has not yet been excavated. The excavators assumed that this structure was a bathhouse used by the villagers. Byzantine period bathhouses have also been found in other large village sites, such as Rameh in the Galilee and Zikhrin in the Judean foothills.

The excavation results allowed the excavators to estimate both the extent of the village at the height of its expansion in the Byzantine period and its number of inhabitants. An underground radar survey established that the synagogue stood in the middle of the village, and that the village had an elliptical shape and an overall area of about 10 a. Assuming an average of 25 people per quarter acre—an accepted formula for calculating population density—the population of the village at its maximum extent would have numbered about one thousand.

The village was destroyed in a fierce conflagration at the end of the sixth or the beginning of the seventh century, which was most likely caused during one of the Bedouin attacks prior to the Persian and Arab conquests. The numismatic finds reveal that the site was abandoned and not resettled until the Mameluke period. Unstable security conditions apparently prevented the rebuilding of the site, leaving the people of En-Gedi no choice but to abandon the village.

THE MAMELUKE VILLAGE. Remains of houses from the Mameluke period (stratum I) were uncovered in various parts of the excavated area. According to the coins and pottery, the village was reinhabited during the thirteenth–fifteenth centuries CE. The houses of stratum I are characterized by their reuse of the walls of houses of the Byzantine period. They are irregular in shape and generally constructed of a single row of fieldstones. Clusters of four to five rooms were discovered at distances of 20–30 m from one another. In addition to the coins and pottery, the finds also include numerous lumps of bitumen, evidence that, as mentioned in literary sources of the period, the inhabitants collected and sold bitumen. A flourmill attributed to the Mameluke period was also uncovered (see below).

THE BATHHOUSE (AREA E). Excavations were renewed in the bathhouse, situated about 200 m northeast of the village. The excavations confirmed B. Mazar’s chronological conclusions that the bathhouse was founded between the First and Second Jewish Revolts against the Romans. It apparently served the unit of the Roman army stationed at En-Gedi, as attested to by the

There were no significant finds west of the bathhouse, aside from a thin wall (0.4 m wide) built parallel to it. Along the wall, at fixed intervals, were holes filled with ash and animal bones (mainly sheep), apparently fertilizer for ornamental plants set along the wall. Sections dug above the bathhouse uncovered typical Dead Sea sediment—a layer of fine sand—reaching the top of the walls. This sediment is also formed today in the shallow lagoons on the shores of the Dead Sea and is evidence of flooding some time after the destruction of the bathhouse. The absence of sherds from the Late Roman-Byzantine period in the sediment indicates that the flooding began in that period. The tops of the walls of the bathhouse were 390 m below sea level, indicating that the level of the Dead Sea was higher than that in the Byzantine period (yet lower than 382 m below sea level, the ground level at the limits of the Byzantine village).

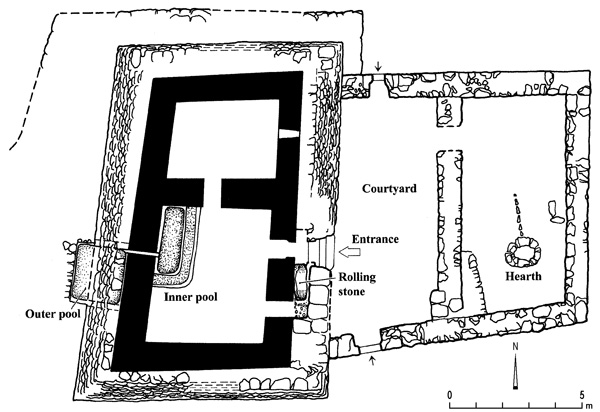

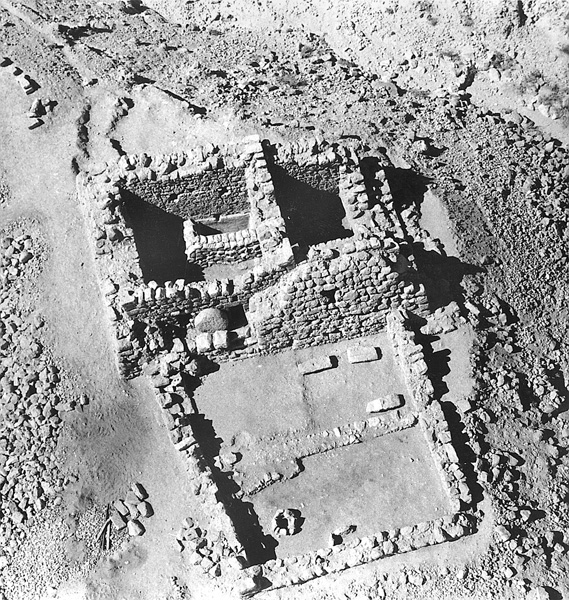

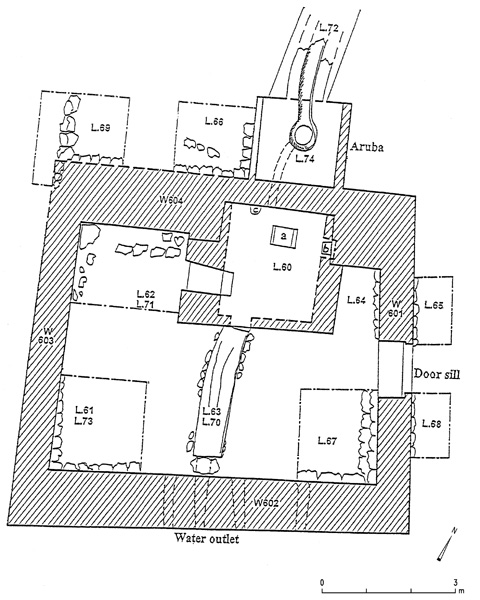

The tower, at least two stories high, is rectangular in plan (11.3 by 6.2 m) and built of large, roughly dressed stones. Its thick walls (1 m) were protected by a stone revetment, 1.1–1.5 m thick at its base and 3.7 m high. On its north side the revetment was reinforced by another massive retaining wall, 1.3 m wide. The interior space of the tower is divided into a front and back room. The entrance to the front room faces the courtyard; a flight of four steps leads up to it. The entrance is quite small (1.2 by 0.57 m) and was closed by a rolling stone, found in situ (1.4 m in diameter, 0.4 m thick), which moved on an inclined track set in the space between the glacis and the wall of the tower.

In a corner of the front room is a rectangular pool (external dimensions 3 by 1.5 m, depth 1.8 m) with walls 0.4 m thick. A water channel passing through the wall of the tower connects the pool with a square external pool (2 by 2 m, 2 m deep), which is coated with light grayish hydraulic plaster. The channel slopes down into the internal pool, indicating that the extraction process of the fluids in the pools commenced in the external pool and was completed in the internal pool. These pools were probably utilized in the production of perfume essence from the balsam plant mentioned for example by Eusebius (fourth century) and Hieronymus (fifth century) as a unique product of the En-Gedi oasis. After extraction, the aromatic essence was heated with oil (olive oil?) to a temperature of 65 degrees C, probably in the fireplace in the courtyard outside the building. Considering the size of

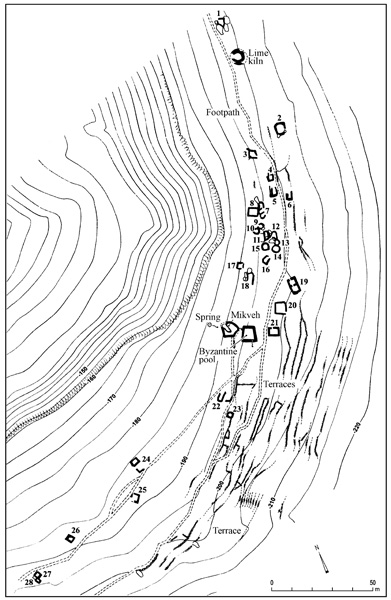

THE ESSENE SITE (AREA H). The Essene site extends over a natural rock terrace, some 200 m above the Dead Sea (i.e., 200 m below sea level) and 800 m southwest of Tel Goren. West of the site is a sheer cliff, 50–60 m high, at the foot of which were a number of springs in antiquity, among them the spring in the center of the site. Discovered in 1956 during a survey conducted by Y. Aharoni, the site consists of 28 chambers or cells dispersed over an area measuring 300 m by 20–30 m. An ancient path connected the site with the village of En-Gedi at the bottom of the oasis.

The cells, which are not interconnected, each having its own entrance, were very simply constructed of rough fieldstones with no bonding material. Cooking stoves and fireplaces with ash were found in some of them. The internal dimensions of the cells are approximately 3 by 2 m; four are square-shaped and larger (5 by 4 m); and the others are irregular in shape. They yielded sherds and fragments of glassware from the first century and first half of the second century CE. Among the pottery are jars, cooking pots, jugs, and juglets. Several coins of the period were also found. Sherds of the Byzantine period appeared in only five of the cells, indicating that the occupation of the site was limited mainly to the Early Roman period.

In the middle of the site are two pools. The upper pool, into which the spring flowed, is irregular in shape (5.5 by 4.7 m, 1.9 m deep) and covered with the gray hydraulic plaster typical of the Early Roman period. A rock-hewn ramp descends to the floor of the pool, where the Essenes probably immersed themselves for ritual purification. The lower pool is square (5 by 5 m), its walls preserved to a height of 1.4 m and bearing the whitish hydraulic plaster typical of the Byzantine period in the En-Gedi oasis. It apparently served for irrigation purposes in the Byzantine period, when the climate was more humid. Also from this period are terraces scattered over an area of 1 a. at the level of the lower pool and below.

In the northern part of the site is a lime kiln, where the plaster for the pools would have been produced. The round kiln has an external diameter of 8 m and an internal diameter of 3.5 m. The opening of the combustion chamber faces northwest.

The site represents two of En-Gedi’s most prosperous periods: the end of the Second Temple period and the Byzantine period. In the first century CE, Pliny described a community of Essenes “who are celibates, use no money, and live together in the shade of the palm trees” (NH 5, 75). According to Pliny, En-Gedi was located “below their dwelling place.” The site can therefore be identified as the place inhabited by Essene hermits in that period. The building remains and finds from the site correspond with Pliny’s description.

YIZHAR HIRSCHFELD

WOODEN COFFINS. In surveys and excavations conducted by G. Hadas in 1984–1988 on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities (now the Israel Antiquities Authority), some 40 wooden sarcophagi were found in family burial tombs at En-Gedi. These are rectangular in shape, most standing on four legs and with gabled lids. They were made of thin planks of sycamore and wooden nails and bound on the outside with a rope made of date palm fibers. The coffins vary in size according to the size of the deceased, ranging from small wooden ossuaries 0.6 m long to a coffin 1.8 m long. Most are plain, but some are decorated. The tombs in which they were found contained primary burials, sometimes in wooden coffins or woven mats and wrapped in linen shrouds, as well as secondary burials in wooden or soft limestone ossuaries. Some of the coffins contained the remains of more than one individual, including some children.

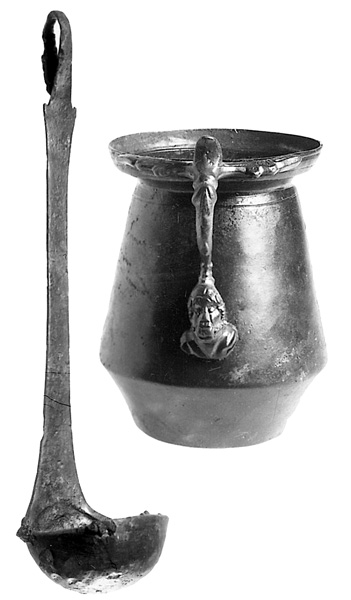

The coffins also contained personal possessions that belonged to the deceased. Some of the objects are made of wood, such as small bowls, combs, and kohl containers. Bronze objects, such as ladles and kohl sticks, were also found. The pottery in the burial caves dates the coffins from the first century BCE to the first century CE.

FLOUR MILLS. Two ancient flour mills were uncovered on the slope beneath the spring in the En-Gedi oasis. The mills were powered by the flow of spring water. They were excavated by G. Hadas in 1997–1998, within the framework of the excavations of Y. Hirschfeld (area F).

The Byzantine water-powered chute mill is located in the middle of the slope, between Tel Goren and the spring. Water reached the mill through a chute c. 6 m long, which branched off from the aqueduct of the En-Gedi spring. The mill is a square structure (5 by 5 m) built of both dressed stones and fieldstones. Originally two stories high, only the lower story was preserved, to a height of c. 2.5 m. The mill consists of two trapezoidal rooms, a southern room and an eastern room. The southern was built of ashlar masonry with a vaulted ceiling, 1.6 m high. The water was fed into this room through an opening (0.6 by 0.7 m) in the western wall, 0.7 m above the floor of the room; it then turned a horizontal overshot wheel that stood above the room’s gray plaster floor; and left the room via an opening in the eastern wall. A turbine, to the upper part of which was attached the upper millstone, was affixed to the lower end of a vertical axle. The millstones (0.9 m in diameter), fragments of which were found near the mill, operated above this room, on the unpreserved second floor. The height of the water column that turned the wheel was 4.5 m. In the eastern room, which was built of undressed stone, no opening was found. A ledge atop its western wall at a height of 1.7 m probably supported a wooden floor of the upper story, from which a ladder descended to the room. Radiocarbon tests showed that the mill was in use in the sixth century CE.

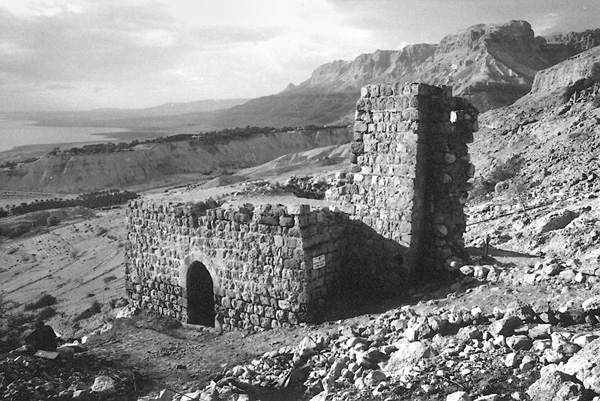

The Mameluke mill, a well-preserved penstock mill, was built near the En-Gedi spring. Only a small section of the stone-built feeder channel that supplied water to power the mill was preserved. The mill structure consists of a large hall (7 by 5.5 m) with an arched opening in the north and a chimney-like tower (3.1 by 3 m), both built of dressed stone plastered on the inside. The millstones are made of basalt and are up to 1.2 m in diameter. A vertical pipe, 0.6 m in diameter, passes through the chimney-like tower. In the wheel cell (2.8 by 2.5 by 0.9 m), situated under the floor of the hall, is an exit hole (0.12 m wide) and a nozzle from which a 6 m head of water erupted and activated the wheel. Found on the floor of the room was typical Mameluke pottery as well as a complete stone (tobacco) pipe of a later period.

IRRIGATION SYSTEMS. In 1981–1985, the irrigation systems in the vicinity of En-Gedi were surveyed and excavated by G. Hadas on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, and in 1996–1998, as part of the Y. Hirschfeld expedition (area G). The results revealed that only four of En-Gedi’s ten ancient springs are active today: En-Gedi, ‘En Shulamit, ‘En David, and ‘En ‘Arugot. Every irrigation system included a spring, a feeder channel, a plastered masonry reservoir, water channels, and irrigated fields on terraces. The aqueducts and reservoirs are built of stone and coated with lime plaster. Twenty-four different types of reservoirs were found in the oasis, the largest with a capacity of 1,000 cu m. Hydraulic lime plaster coatings of earlier and later periods could be distinguished in them. The later plaster often contained potsherds. One of the reservoirs, which was blocked after the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, contained sherds, coins, and a complete Herodian lamp.

Forty terraces were excavated in the oasis, in an attempt to identify agricultural crops cultivated in ancient times. Most of the terraces are dated to the Byzantine period. Each contained a thin light-colored layer of eroded soil forming the upper stratum. Beneath this stratum was a gray layer of cultivated soil, up to 1 m thick, which contained sherds, coins, fragments of glassware, ash from cooking stoves, charred wood, and animal bones, all prepared in the village as compost and brought to the fields to enrich the soil. In all the terraces were found freshwater snail shells, evidence that the irrigation water came from springs rather than run-off. Most of the terraces also contained remains of palm trees but no sign of the opobalsamum plant, although it is mentioned in the sources as one of the main crops of En-Gedi at this time.

ANCHORS. Stone and wooden anchors found at the site are additional evidence of maritime activity in the Dead Sea during the Hellenistic/Hasmonean period. Three stone anchors were discovered on the shore of En-Gedi by G. Hadas in 1989. The anchors are made of local limestone and are rectangular in shape (0.6 by 0.4 by 0.3 m), rounded on the corners and perforated (0.16 by 0.10 m) on top. The anchors weigh 110–134 kg. Two of the anchors contained pieces of rope made of date palm leaves, one 6 cm in diameter and 20 cm long and the other a two-strand rope, 3 cm in diameter and 160 cm long. Radiocarbon tests of the ropes indicate a date from the end of the third to the beginning of the second century BCE. Another anchor, with no remains of rope, was also found on the shore.

Two wooden anchors with remains of ropes were found at the beginning of 2004. One anchor has a lead shaft and two arms, and dates to the Early Roman period. The other has a stone shaft and a single arm, and dates to approximately 500 years earlier.

SETTLEMENT REMAINS WEST OF THE SYNAGOGUE. In 2003–2005, three seasons of excavations were carried out in a settlement west of the synagogue. The settlement, with a single occupation level, was apparently a residential quarter situated at some distance from the center of the En-Gedi village. It was destroyed in the second year of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome. Each of the houses has a courtyard and a dwelling room. The courtyards contained ovens, cooking stoves, potsherds, fragments of hand and lathe-made chalk vessels, and numerous coins. A number of empty pottery vessels were found buried beneath the floors of the houses.

GIDEON HADAS

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

The latest excavations at En-Gedi were conducted during seven consecutive seasons from 1996 to 2002, under the direction of Y. Hirschfeld on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The excavations focused on seven areas in the En-Gedi oasis: the Roman-Byzantine village (areas A, C, D), the Roman bathhouse (area E),

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE ROMAN-BYZANTINE VILLAGE (AREAS A, C, D). During the course of the excavations a large area of about 1 a., one-tenth of the total area of En-Gedi, was uncovered north of the synagogue. This area was described by Eusebius in the fourth century CE as a large Jewish village where the balsam plant (opobalsamum) was cultivated. The village was densely built up with houses in very close proximity to each other; building remains were encountered wherever an excavation area was opened. Four main settlement strata were distinguished in the village, dating to the Early Roman (stratum IV), the Late Roman and Byzantine (strata III–II), and the Mameluke periods (stratum I).