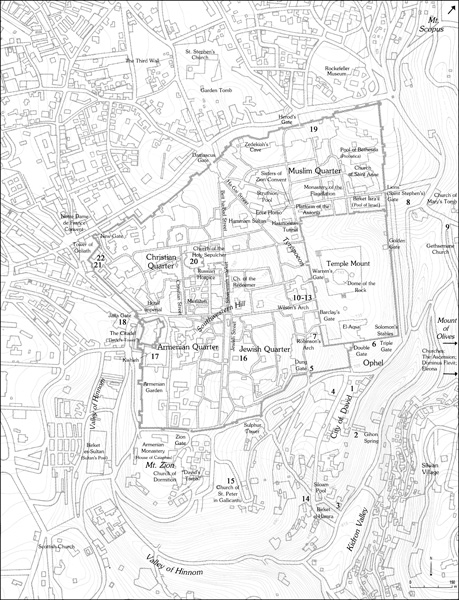

EXCAVATIONS WITHIN THE ANCIENT CITY

1. THE CITY OF DAVID VISITORS’ CENTER

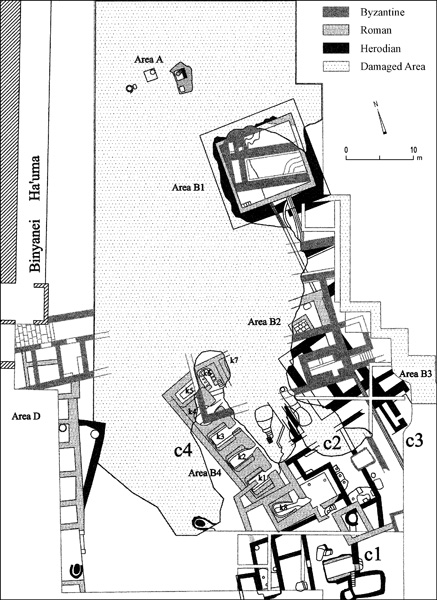

In 2005, excavations were conducted in the area of the visitors’ center on the northern part of the southeastern hill of ancient Jerusalem, identified with the biblical City of David. The excavations were directed by E. Mazar, on behalf of the Shalem Center and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The area had largely been excavated in 1923–1925 by J. G. Duncan and R. A. S. Macalister. It is located several meters northwest of the Stepped Stone Structure uncovered on the northeastern slope of the hill (Shiloh’s area G).

In the Middle Bronze Age, an open flat area was created in the area by the quarrying of bedrock and the depositing of fills of crushed limestone. Above this surface was an earth accumulation containing Middle Bronze Age, Late Bronze Age, and Iron Age I sherds. At an early stage in the Iron Age IIA (the tenth century BCE), a structure built of very large stones, referred to as the Large Stone Structure, was erected in this location. Its massive walls, 2.0–5.0 m wide, consist of particularly large untrimmed stones, and extend over the entire excavation area and even beyond it. The Stepped Stone Structure and Large Stone Structure appear to constitute a single architectural unit, the former built as a support system for the latter. In the opinion of E. Mazar, this construction was overseen by King David, having been erected outside the city wall and the citadel at the high northern end of the City of David, perhaps the biblical Citadel of Zion. The ashlars and Proto-Aeolic capital found by K. Kenyon in adjacent collapses to the east (her square A/XVIII) probably originated in this building. In one room in the northeastern part of the Large Stone Structure was found evidence for two secondary construction phases dated to a subsequent phase in the Iron Age IIA. A bulla bearing Paleo-Hebrew script, reading “Belonging to Yehuchal, son of Shelemiyahu, son of Shovi” was found in the excavations. An individual by this name held an important position during the reign of King Zedekiah, as mentioned in Jeremiah 37:3 and 38:1. The building remained in use until the end of the Iron Age.

A few remains from later periods were found in the excavations. From the Herodian period are plastered pools and a mikveh dug into building remains of the Iron Age and incorporating large stones from a previous construction. From the Byzantine period was uncovered a room paved in white mosaic, part of a house with a peristyle courtyard largely exposed by Macalister and Duncan and referred to by them as the House of Eusebius. The latest of the remains found in the excavation area is a pit that contained Abbasid (tenth-century

EILAT MAZAR

2. THE GIHON SPRING AND EASTERN SLOPE OF THE CITY OF DAVID

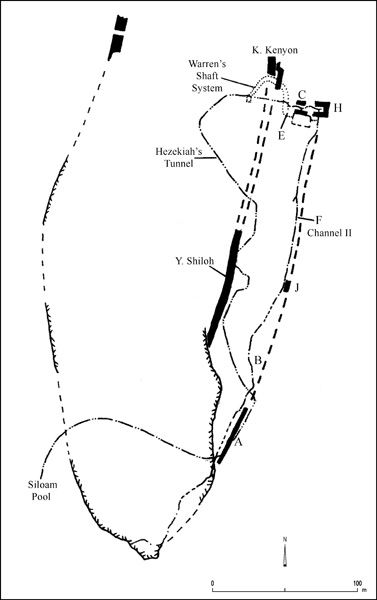

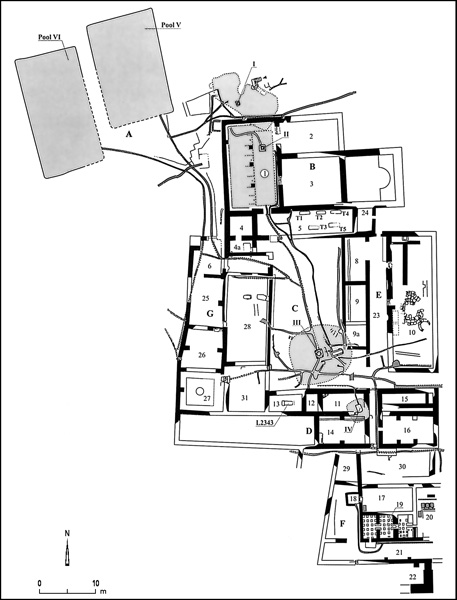

Renewed excavations took place in the area of the Gihon Spring and the lower Kidron Valley, on the eastern slope of the southeastern hill of ancient Jerusalem. The excavations were conducted in 1995–2004 by R. Reich and E. Shukron on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. Some of the new excavation areas adjoined ones previously excavated. Others were in areas that had not been explored.

CHALCOLITHIC PERIOD AND EARLY BRONZE AGE FINDS. The earliest pottery sherds were found in area B, which adjoins Y. Shiloh’s areas B and D1. In the rock crevices under the Iron Age II houses were several handfuls of Chalcolithic period and Early Bronze Age I pottery sherds. Pottery of the Early Bronze Age I was also found inside the southern cave of the Warren’s Shaft complex, indicating that it served as a dwelling during that period.

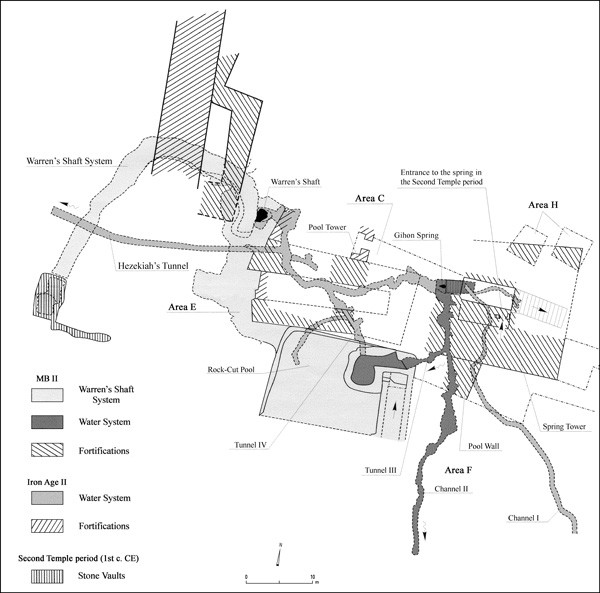

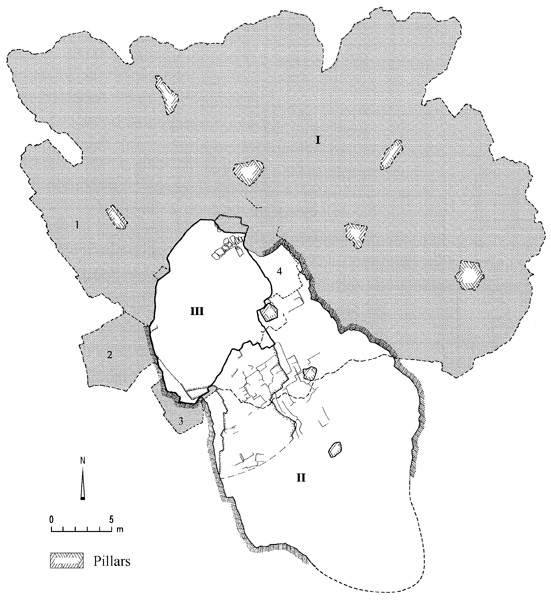

MIDDLE BRONZE AGE II REMAINS. The main excavation area lay south and west of the Gihon Spring (area C). This area had never been excavated.

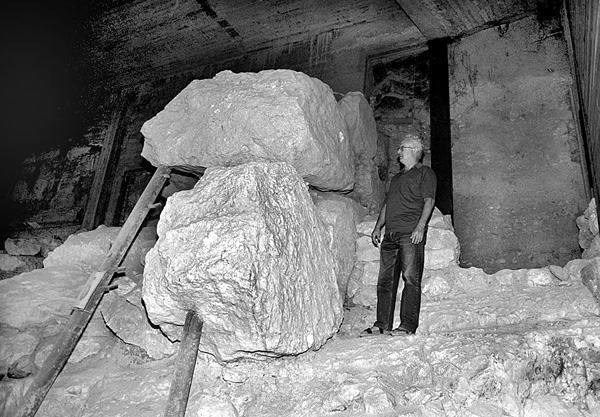

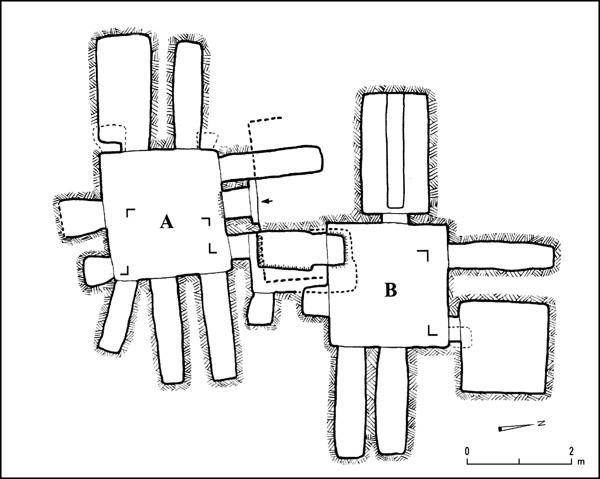

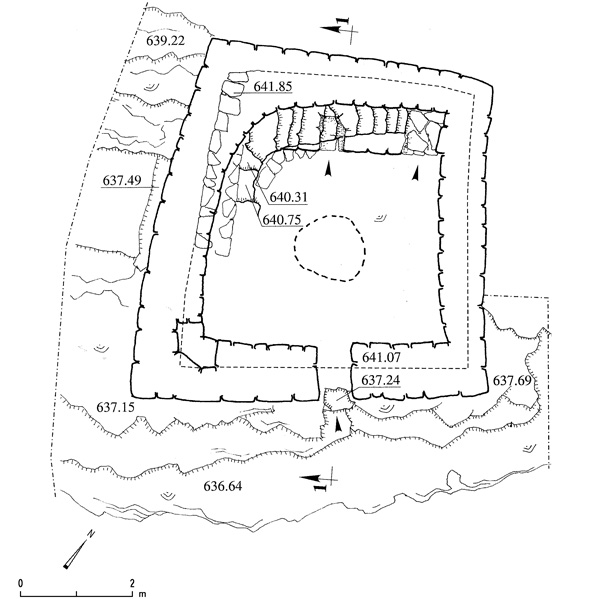

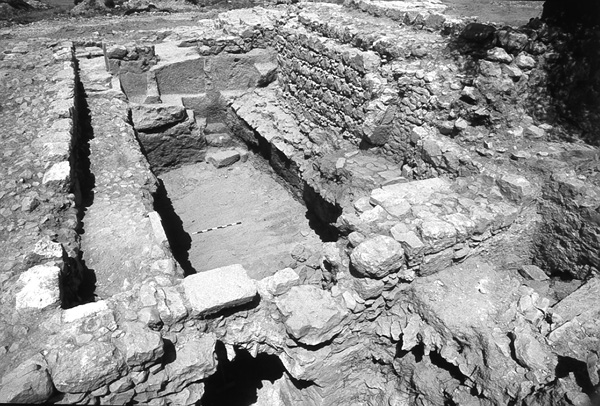

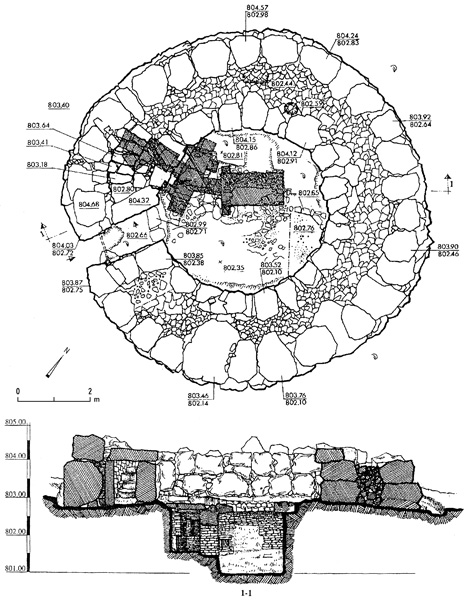

The Spring Tower. The recent excavations exposed a monumental, rectangular-shaped structure built around the spring to protect it. This has been named the Spring Tower. Its southern wall was exposed in its entirety. The tower’s external dimensions are 17 by 16 m, with a room c. 10 by 5 m in its interior. The eastern wall of the tower rests on the Kidron Valley bed. Remains of its eastern and western faces indicate walls c. 7 m thick. The tower abuts a rock-cut step on the west. Similar to the Pool Tower exposed further to the west, the Spring Tower incorporates large boulders with average dimensions of 1.5 by 1.2 by 1 m, and an average weight of 3–4 tons. A 3.2-m-long stone was exposed in the inner face of its western wall. This is the largest construction known in Jerusalem prior to the Herodian masonry of the first century BCE. Although these boulders are quite rough, having simply been dislodged from the rock terraces of the hill, they are set in courses to form straight vertical faces.

Channel II. As a separate technical phase preceding the construction of the Spring Tower, channel II, which carries the spring water southward, was cut into the eastern slope of the Kidron Valley. The first segment of channel II was partly uncovered by C. Schick in 1886 and 1890. Other scholars who excavated parts of it or reexamined known segments were M. Parker (1909–1911), R. Weill (1913–1914), and Y. Shiloh (1978–1985). From 1995 to 2001, R. Reich and E. Shukron exposed three other portions of the channel. The first is its entire northern segment, extending from the spring for a distance of 130 m to the south (area F; the first roughly 65 m of this segment had been previously examined by Parker). The second is a point 190 m south of the spring where the channel becomes a quarried tunnel; excavations ensued from this point northward for a distance of 13 m. The third is a 32-m-long tunnel segment of the channel, excavated c. 280 m south of the spring (area A).

The depth of the channel varies according to the level of the rock surface. In some places it is as much as 5 m deep. Since the southern wall of the Spring Tower is built over the covered channel, the channel is most probably contemporary with the Middle Bronze Age II water system. Previously, the channel, which is elsewhere referred to as the Siloam Tunnel, had been regarded as separate from the other waterworks of the City of David. As a result of the findings of the new excavations, the excavators now consider the northern part of channel II—that extending 190 m southward from the spring—to have been an integral part of the Warren’s Shaft system, created to feed the Rock-Cut Pool. The entire water system, including channel II, is thus dated to the Middle Bronze Age II. Excavation at the point of transition from the covered channel to the tunneled channel revealed that originally the covered channel turned sharply to the east at this point while the tunnel appears to be a later prolongation of the channel dating to the late Iron Age II.

The Rock-Cut Pool. Southwest of the Gihon Spring is an extremely large pool cut into the hard mizzi

The Pool Tower. Abutting the northern side of the pool is another monumental construction. It has two thick parallel walls constructed of huge boulders, leaving a narrow space between them. The eastern edges of these walls were later discovered inside the caves at the southern end of the Warren’s Shaft system. Middle Bronze II pottery was retrieved above and under the floor in this space. Another floor which contained such pottery was located at the junction of the Warren’s Shaft system and the northwestern corner of the pool. Additional Middle Bronze II pottery, a scarab, and a scarab impression on a storage jar sherd were found associated with the thick walls and the rock surface upon which the walls rest.

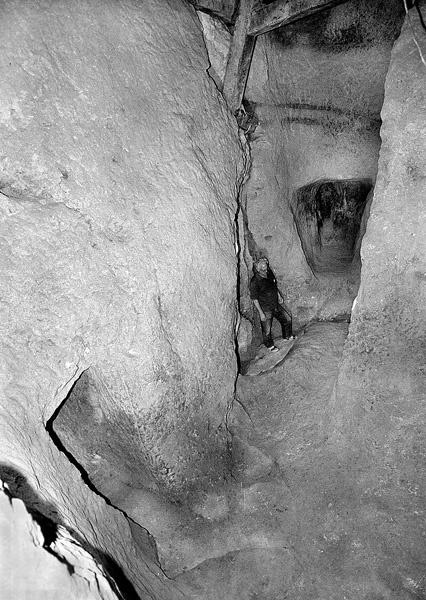

The Warren’s Shaft System. These findings prompted a reexamination of the Warren’s Shaft system, which was discovered by C. Warren (1867), excavated by M. Parker and L. Vincent (1909–1911), and reexamined by Y. Shiloh (1978–1985). The renewed excavations and examination of the system (area E) took place in the two caves at its southern and lower end: the southern cave, which connects the system to the Rock-Cut Pool; and the northern cave, which is above Warren’s Shaft. The rocky floor of the southern cave and a small niche within it produced Early Bronze I pottery of the type already discovered by Parker and Vincent, which attests that these originally were Early Bronze Age dwelling caves. A crushed limestone floor was exposed at a higher level; Middle Bronze Age II pottery was retrieved from above and below the floor. A roughly 0.5-m-thick layer of stonecutters’ waste consisting exclusively of hard mizzi rock was encountered overlying the layer with Middle Bronze Age II pottery. It contained three oil lamps of the eighth century BCE.

Bedrock in this area is clearly divided into two distinct rock formations—an upper layer of soft meleke resting above a lower, hard mizzi layer. It had previously been commonly held that the Warren’s Shaft system was created when an existing, long and winding natural cavity in the bedrock was enlarged. According to this theory, the tunnel was cut in a single operation through both upper and lower rock formations to reach the vertical natural cavity located at its end. The renewed excavations and subsequent study by Reich and Shukron have led to a new theory regarding the system, which holds that the entire system was cut in two phases rather than one. In the original phase, the tunnel was cut exclusively into the upper, softer rock layer; the hard rock layer below served as the tunnel floor. This tunnel reaches the southern cave and emerges at the Rock-Cut Pool. It dates to the Middle Bronze Age II, together with the Spring Tower, Pool Tower, Rock-Cut Pool, and channel II. In this phase, the vertical Warren’s Shaft, a natural dissolution chimney (as demonstrated by D. Gil’s geological examination), had not yet been encountered, as it does not reach the top of the hard stone formation. It was thus inaccessible and played no part in the original system. In the second phase, which dates to the eighth century BCE, the tunnel was deepened for unknown reasons, penetrating the hard rock layer below. It was then that the natural shaft was first discovered. This deepening also hindered free access to the Rock-Cut Pool. The water supply to the city does not appear to have been hindered at this point, as it had come to largely depend on Hezekiah’s Tunnel, which was also cut in this period.

No pottery sherds of the Late Bronze Age or the Iron Age I were encountered in the areas excavated near the spring (areas C, E, H). This may be relevant to the debate on the character of Jerusalem during these periods, though it must be added that no sherds from the Persian, Early Hellenistic, Byzantine, and Early Islamic periods have been found near the spring either.

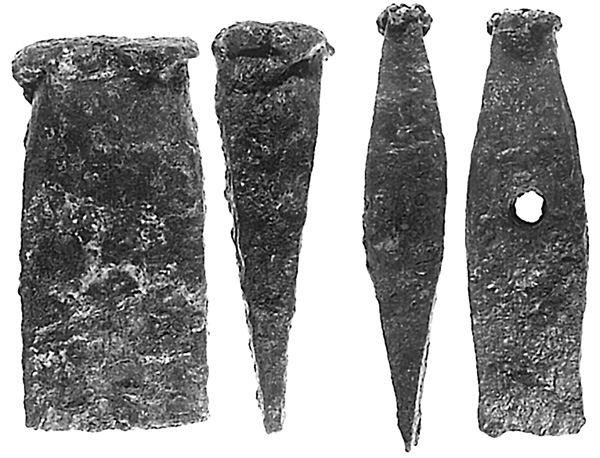

IRON AGE II REMAINS. Area C. In several places, the monumental towers and the Rock-Cut Pool were covered with debris containing eighth-century BCE pottery. Repairs made with smaller stones were observed in some places, such as on the southern wall of the Spring Tower. It seems that the Warren’s Shaft system of the Middle Bronze II was accessible and continued in its original use into the late Iron Age. During this period the openings of the two caves at the eastern edge of the Warren’s Shaft system were blocked with a wall of small stones. Outside one of these walls and abutting the northern face of the Pool Tower was a room, and near the blocked opening of the northern cave was a floor containing two groups of dried-mud loom weights typical of the Iron Age II, as well as charred wood. This evidence suggests that during the late Iron Age II the passages connecting the Rock-Cut Pool and horizontal tunnel were blocked and the inner parts of the Warren’s Shaft system, as well as the area outside of it, were used as dwellings.

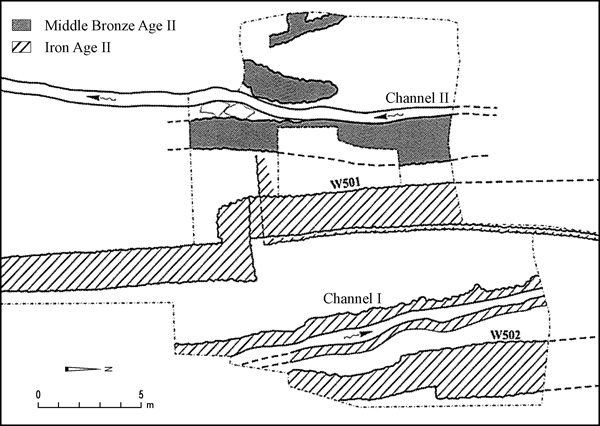

Channel I, originally discovered by E. Masterman in 1901, was recleared at the bottom of the present-day fountain house standing over the spring. It runs a winding southward course. It should be dated to the Iron Age II, as established by another segment of it exposed in areas A and J. Its function remains unclear. At the easternmost point of area C, close to the lowest level of the Kidron Valley, a c. 2-m-wide segment of the city wall, constructed of small stones and preserved to a height of at least 6 m, was encountered. Pottery extracted from the earth abutting its eastern face dates its latest use to the eighth century BCE; its foundation trench was not reached during excavations.

Area J. The city wall revealed in area C probably joins the 2-m-wide wall uncovered in area J (wall 501), preserved to a height of over 5 m. The wall is built of small fieldstones and is founded on bedrock. A segment c. 35 m long was traced in the area, including a sizeable offset constructed of large stones. The pottery from the earth deposit over the wall, as well as that abutting its western side, dates to the eighth century BCE. Two similar walls were revealed running parallel to this wall, one several meters to its east and the other a similar distance to its west. A segment of channel I, clearly dated here to the eighth century BCE, was exposed between the central and eastern walls, at a lower level than channel II. The eastern wall was founded very close to the bed of the Kidron Valley.

These constructions seem to reflect the addition of a modestly sized area, c. 1.5 a. at the most, to the city in the eighth century BCE. It likely accommodated the natural growth of Jerusalem. While the city experienced a considerable westward expansion in the eighth century, as evidenced by the N. Avigad excavations in the Jewish Quarter, this eastward fortified expansion may have been earlier. It is perhaps identifiable with the area referred to in the Bible as “between the walls” (Is. 22:11; Jer. 39:4, 52:7).

Area A. Excavations along the Kidron Valley bed, c. 200–250 m south of the spring, revealed the eastern face of a long wall constructed of small fieldstones and founded on bedrock. Its precise thickness could not be established, but it clearly is a southern continuation of the eighth-century BCE city wall exposed in area J. Along the eastern, extramural face of this wall ran a rock-cut channel, several cover stones from which survived. According to its location in relation to the wall and to its bottom levels, it appears to be part of channel I. In this spot, as in area J, the channel was dated on the basis of pottery to the eighth century BCE.

Area B. Excavations in area B, an extension of Y. Shiloh’s areas B and D1, revealed the remains of three private houses of the eighth century BCE. The houses are built upon a rock terrace, their western parts hewn into bedrock, their eastern parts raised upon retaining walls. In addition to pottery, concentrations of dried-mud loom weights typical of the period were retrieved. Other private houses had been revealed in this area during excavations by Shiloh, who argued that they were part of an extra-mural quarter, located below the city wall that he exposed at mid-slope. However, as the houses are contemporary with the city wall segments recently exposed by Reich and Shukron at the foot of the slope, they should be understood as always having been intra-mural. The houses excavated by both expeditions are oriented along a north–south axis, indicating a planned quarter.

PERSIAN PERIOD FINDS. No pottery of the Persian or Early Hellenistic periods was found in the vicinity of the spring. In area A, c. 240 m south of the spring, some earthen deposits, dumped from the eastern slope of the City of David to the Kidron Valley, contained Persian period pottery including several jar handles with yhd seal impressions.

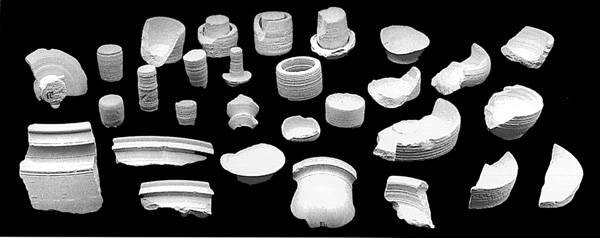

THE HERODIAN PERIOD CITY DUMP AND OTHER REMAINS. Each of the areas excavated on the eastern slope of the southeastern hill contained an extremely thick (8–10 m) deposit of loose earth, rubble, large amounts of broken pottery, stone vessels, animal bones, and other finds. This accumulation of debris covers the entire length and width of the slope, extending northward to the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount. There were no walls associated with the debris. The artifacts recovered from it date mainly to the first centuries BCE and CE, up to the year 66 CE; no coins of the First Jewish Revolt were found.

The accumulation had been previously encountered and described by all past excavators of the eastern slope of the southeastern hill, including Warren, Schick, Parker, Macalister, Kenyon, and Shiloh. It should be identified as the city dump of the Herodian period. Containing at least 200,000 cu m of material, it seems to have been the result of an organized and continuous effort to deposit waste material in this area of the city, which had previously served as a city dump in the Iron Age and Persian periods. As this dumping activity was potentially hazardous to the spring and might have blocked access to it, some unsuccessful, simple terrace walls were constructed close to the spring to prevent the garbage from sliding down the slope. Once this proved ineffective, a barrel-shaped stone vault was built above the spring; the vault still survives as the inner part of the fountain house. Its first-century CE date is attested by pottery covering its extrados.

In the late Second Temple period, the space within the Spring Tower was refurbished as a fountain house. Surviving from this structure are its doorway, built of well-cut ashlars, and the remains of several stone steps descending to the spring. The approach to the spring and its protection would have been necessary measures given the specific cultic uses of the spring water in the temple.

A concentration of several scores of intact cooking pots, in several layers, was discovered in area A, east of the Iron Age II wall. It appears to be one of several such concentrations already known from other locations around the city’s perimeter. The vessels are of the types prevailing in the late second–first centuries BCE. Several isolated cooking pots were also found in area J.

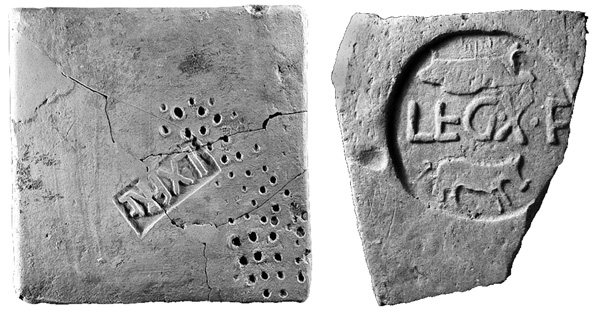

LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE REMAINS. Considerable quantities of Late Roman period pottery sherds were found in areas H and C in the vicinity of the spring. The pottery predominantly includes storage jars and deep kraters with flaring rims. Roof tiles, one bearing a seal impression of the Tenth Roman Legion, were also recovered. These finds were deposited between several thin layers (c. 20 cm each) of fine-grained silt or clay. Remains of an earthen dam incorporating several boulders taken from the adjacent Middle Bronze Age II Spring Tower were found in area C. It extended eastward across the Kidron Valley from the Spring Tower. This dam held back rainwater and silt, perhaps for agricultural purposes or for obtaining clay for pottery production. The level of the uppermost silt layer is higher than the apex of the vault above the spring, indicating that access to the spring was blocked during this period. It was not reopened until the Mameluke period.

No Byzantine or Early Islamic pottery was found in the areas excavated near the spring, as access to the spring was blocked in the Late Roman period and activity had moved to the Pool of Siloam at the southern end of the hill. A small excavation on the southern side of the hill, near the Meyuhas House (area D), exposed part of an ancient quarry. Several coins found in this spot indicate that the quarry dates to no later than the late Byzantine period.

MAMELUKE PERIOD REMAINS. Mameluke period (c. fourteenth-century

RONNY REICH, ELI SHUKRON

3. THE POOL OF SILOAM

In 2004, the remains of a large stepped pool were found on the eastern side of Birkat

Construction of the first phase of the pool is securely dated to the mid-first century BCE on the basis of several coins embedded in the plaster. The second phase dates to the first century CE. Considerable amounts of pottery sherds and 12 coins of the First Jewish Revolt date the abandonment of the pool to the year 70 CE, followed by a process of rapid silting. The pool should thus be identified with the late Second Temple period Pool of Siloam, which appears in historical sources (Jn. 9:7). The Byzantine period Pool of Siloam was constructed further to the north, near the outlet of Hezekiah’s Tunnel.

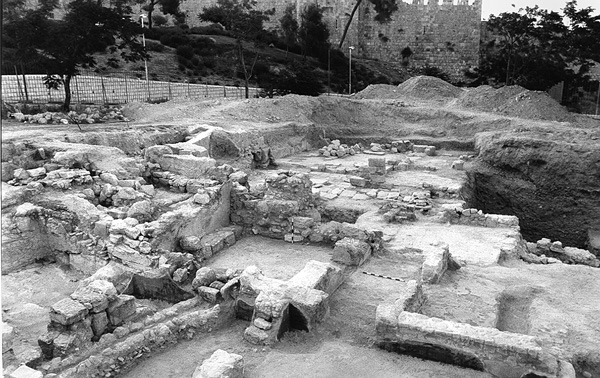

4. THE GIV‘ATI PARKING LOT

An excavation was begun in 2003 in the Tyropoeon Valley, to the southeast of the Dung Gate, under the direction of E. Shukron and R. Reich and on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The site lies west of areas excavated by R. A. S. Macalister and J. G. Duncan in 1923–1925, and north of areas excavated by J. W. Crowfoot and G. M. Fitzgerald in 1927.

A small amount of late Iron Age II pottery was encountered in the excavations. The earliest architectural remains, however, date to the late Second Temple period. These include a partially preserved stone vault, which abuts an earlier, as yet undated wall built of large stones; the lower part of a stepped, plastered mikveh; and remains of a floor and walls dated to the second century BCE.

Two main phases dated to the Byzantine period were identified. Constructed in the earlier of the two were long east–west walls with deep foundations. Beaten earth or plain tessellated floors were associated with them. A typical Byzantine period cistern supported by arches was constructed between the main walls and plastered with a mixture containing worn pottery sherds. During the later phase, some of the walls were severed on the east to create space for a stone-paved alley. No traces of destruction were found and the area appears to have been abandoned at the end of this phase.

The Early Islamic period stratum was encountered only in the eastern part of the excavated area. It included walls incorporating building stones from previous strata. An extraordinary find from this stratum is a small marble fragment with the remains of a Hebrew inscription mentioning bar ya‘[aqov], “son of Jacob.” The find supports the identification of this part of Jerusalem as a neighborhood inhabited by Jews during this period, as attested in historical sources. The very thick upper layer (c. 4–5 m) encountered in the excavation area was devoid of construction remains. Its deposition began in medieval times, when the area was abandoned.

5. THE DUNG GATE AREA

Remains of the Secondary (Eastern) Cardo were uncovered on the western edges of an excavation area located within the present-day Old City walls just west of Dung Gate, below the escarpment at the eastern side of the Jewish Quarter. The excavation was conducted by R. Reich, Y. Billig, and Y. Baruch on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. Small segments of this street had previously been excavated by C. Warren (1867), C. N. Johns (1930s), and M. Ben-Dov (1980). Some of the street’s features—a drain under the paving in the middle of the street, the laying of the thick flagstones diagonal to the street’s axis, and the shape of the adjacent column bases—differ considerably from those of the Cardo, which was exposed in the Jewish Quarter. It appears to have been paved during the Late Roman period and remained in use through the Byzantine period. In the Early Islamic period, Umayyad palace III was erected along its eastern side. The southern continuation of this street outside the present-day Old City wall was excavated by M. Ben-Dov.

Considerable portions of the Umayyad palaces were first exposed by the B. Mazar expedition. R. Reich, Y. Billig, and Y. Baruch have extended the excavation of palace III (as referred to by the B. Mazar expedition), which lies southwest of the Temple Mount, next to the Dung Gate. A large part of the southern side of palace III was exposed, as was its western wall, which abuts the Secondary Cardo. It turned out to be a far larger edifice than the Mazar expedition realized, measuring 79 by 75 m. From a western gate opening onto the Secondary Cardo, one enters a wide, paved corridor bisecting the western wing of the building and leading to the inner courtyard. Entrances from this corridor lead to the north and south. The southwestern part of the building (c. 27 by 35 m) was also cleared in the excavations. It contained four rows of five large rectangular piers that apparently supported groin vaults. Part of the stylobate of the colonnades that stood around the inner courtyard were encountered north of and parallel to the southern wing of the palace.

Four long, narrow spaces were excavated in the southeastern quarter. Two wider spaces in this area of the palace had previously been excavated by the B. Mazar expedition (1968–1978). Its foundations reach a considerable depth. (The W. Davidson Visitors’ Center was constructed in these spaces.) Between the thick, c. 2.5-m-wide walls, the excavation descended only 6–9 m below the floor level of the main palace, a small part of which had been exposed by B. Mazar. Bedrock was found, by boring, to lie considerably deeper. The spaces between the exposed walls in this area, which are at the foundation level of the building, were filled with carefully laid beds of earth and gravel. This bedding raised the level of the terrain, creating broad, horizontal spaces for the floors of this and the adjacent large buildings, all erected on a naturally sloping area. The earth fills contain fragments of various artifacts and coins, the latest dating to the late Byzantine and Early Islamic periods.

The uppermost stratum over the entire area northwest of Dung Gate comprised a residential zone of small houses constructed of thin walls of fieldstone. In the houses were many small, rectangular vats lined with high-quality hydraulic plaster. The small finds, particularly the large amount of pottery found within the houses, are characteristic of the Mameluke period. Installations related to an unknown craft were also present.

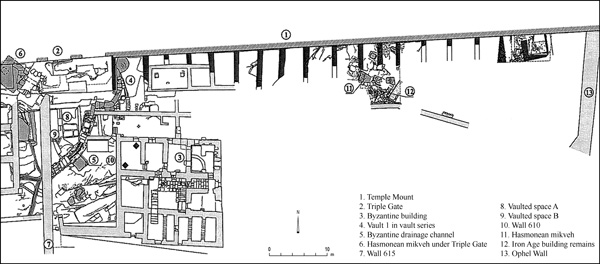

6. THE HULDAH GATES AREA

During a tourism development project in the Huldah Gates area, along the southern wall of the Temple Mount, some probes were made by Y. Baruch and R. Reich in 1997–1999 on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The greater part of this area had been exposed by the B. Mazar expedition. The principal findings in the vicinity of the Triple Gate predate Herod’s enlargement of the Temple Mount. The entrance chamber to the large mikveh underlying the gate was exposed; the rock-cut steps descending into the mikveh were found to have a rock-cut partition down the middle of the steps. Next to the mikveh, a staircase ascends from southwest to northeast; it was partly rock-cut and partly constructed of flagstones.

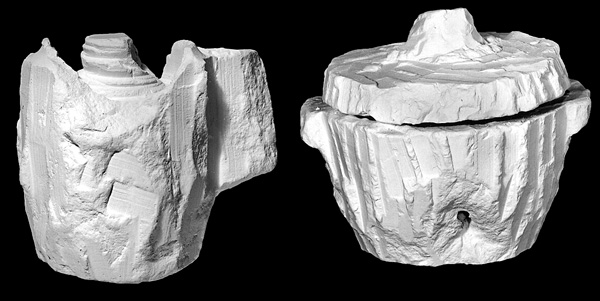

The excavations reexamined the rock-cut vaults and spaces south of the Triple Gate, upon which the monumental Herodian staircase ascended to the gate. Several stone stair treads and part of a handrail from this staircase were found in secondary use in a nearby Byzantine period building excavated by B. Mazar. The dismantling of a small segment of the easternmost wall of Umayyad palace V yielded several spolia from the Herodian Royal Stoa. These include large column bases and drums, c. 1.0 m in diameter, and a large cornice decorated with rosettes and swastikas.

A small probe was sunk at the southern wall of the Temple Mount, c. 10 m west of the southeastern corner of the enclosure. Some wall fragments, floors, and pottery sherds dated to the late Iron Age II were uncovered, as were a few walls and a mikveh shown to have been damaged when the massive Herodian southern wall of the Temple Mount was constructed.

RONNY REICH

7. THE ROBINSON’S ARCH AREA

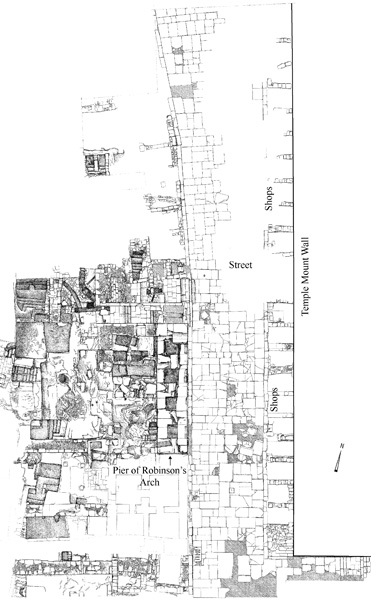

In 1994–1996, excavations were resumed in the Robinson’s Arch area, the first since the conclusion of the large-scale excavations in this area directed by B. Mazar. The renewed excavations were directed by R. Reich and Y. Billig, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

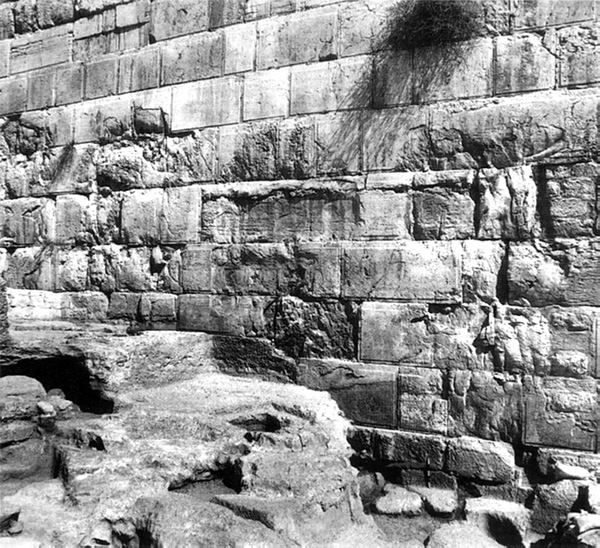

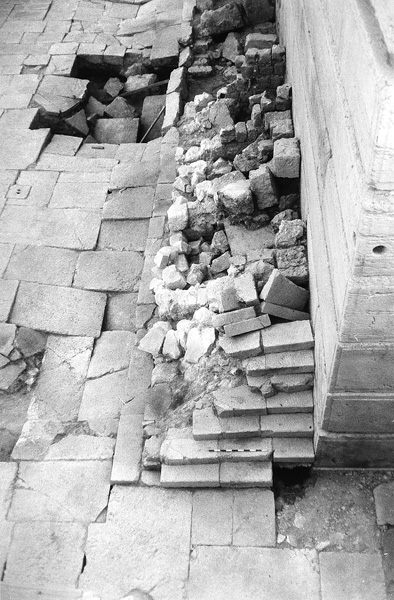

The main architectural remains exposed west of the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount, which had been partially exposed by C. Wilson (1865), C. Warren (1867), and B. Mazar, consist of a 70-m-long segment of the paved Herodian street and the façade of the pier of Robinson’s Arch. The street runs along the western wall of the Temple Mount. It is paved with large, well-cut stone slabs of various sizes, the largest 3.20 m long, laid in no apparent pattern. The stone slabs are 25–40 cm thick. All the stones were found intact and in situ, except in one spot where the impact of the collapse of Robinson’s Arch severely damaged the street. The width of the street between two raised curbs is c. 8.5 m.

A date for the construction of the street was established in the excavations. A probe under one of the flagstones of the street revealed several coins, the latest of which dates to Pontius Pilate (26–36 CE; an additional coin from 67 CE seems to be intrusive). It seems that, although the street was planned as part of Herod’s building program on the Temple Mount, it was paved only in the last generation before the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE. This also accounts for the unweathered state of the street’s flagstones.

The street does not abut the western wall of the Temple Mount, but runs parallel to it at a distance of c. 3 m, leaving a space in which a row of small chambers was constructed. These chambers, 21 of which were identified, have uniform measurements of c. 3 by 3 m. They opened onto the street, and most probably served as shops, though they were found almost completely devoid of artifacts. Similar chambers were situated on the western side of the street, four of which were located in the pier of Robinson’s Arch; these were excavated by B. Mazar. The street apparently served as the main commercial thoroughfare in the city.

The street’s pavement was found covered with a thin (3–5-cm-thick) layer of debris containing pottery sherds, animal bones, and some 130 coins, having accumulated once the street was no longer cleaned and maintained. The latest coin is of the fourth year of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (69

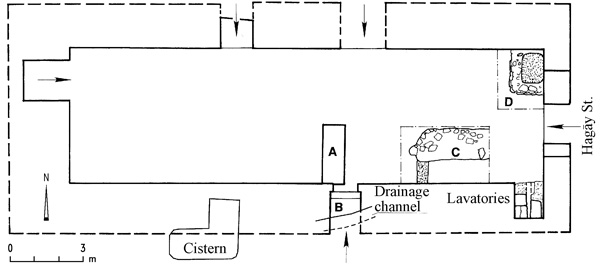

The dismantling of the eastern wall of Umayyad palace IV, adjacent to the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount, revealed that it incorporated parts of a Roman building, most probably a latrine. Parts of this latrine had been exposed by the B. Mazar expedition. A dozen flat stones of the presumed latrine bear carved decorations and inscriptions, allowing for their identification as spolia originally used as seats of a theater or some other public assembly hall. These stones were then incorporated into Umayyad palace IV. There is no evidence for the date of construction of the theater or its location, though it must have been in close proximity. It may have been the theater said to have been built by Herod, or the one constructed for the Roman city of Aelia Capitolina.

An intact, inscribed milestone bearing the names of Vespasian and Titus, as well as that of the Tenth Roman Legion, was found in secondary use in Umayyad palace II, south of the Temple Mount. The name of the legate was completely erased. The Romans fashioned the milestone from one of the rounded handrail stones from the monumental staircase that led over Robinson’s Arch. This provides evidence that the handrail, and perhaps the entire arch, was destroyed no later than 79 CE. An identical inscription, albeit fragmentary, was discovered in this area by the B. Mazar expedition.

A small cemetery exposed along the western wall of the Temple Mount appears to have been in use in medieval times. The B. Mazar expedition encountered its earliest burials, which date to no later than 1099 CE. Now more than 30 additional burials have been revealed. The diversity of burial practices in this cemetery may suggest various ethnic groups, interred over a considerable length of time. A Hebrew inscription citing Isaiah 66:14 was discovered by B. Mazar on one of the stones of the western wall. Mazar dated it to the mid-fourth century CE, the days of Julian the Apostate. However, it may now be understood as having been directly related to the cemetery, and should thus be dated to around the eleventh century CE.

RONNY REICH, YAAKOV BILLIG

8. THE AREA TO THE EAST OF THE TEMPLE MOUNT

Only a few small-scale excavations have been conducted in the area immediately to the east of the Temple Mount. In 1869, C. Warren found remnants of a solid wall in one of several shafts he excavated east of the Golden Gate. In 1890, W. M. F. Petrie noted a rock-cut staircase ascending from the Kidron Valley toward the Lions’ Gate. In 1935, R. W. Hamilton excavated an area south of the junction of the road from the Lion’s Gate and the Jericho road, and discovered Byzantine tombs. In 1995, R. Reich and E. Shukron excavated on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority near the Greek Orthodox Church of St. Stephanos, focusing on two separate excavations areas: area A, c. 50 m due east of the Golden Gate; and area B, at the turn of the Ophel road as it leads east toward the junction with the Jericho road.

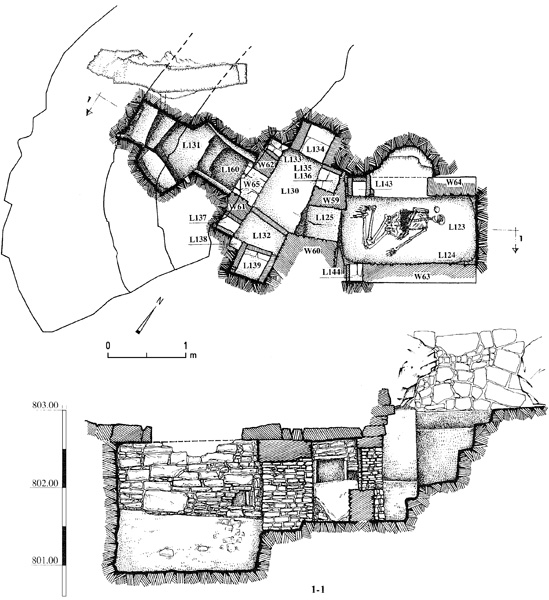

Although the earliest finds discovered consist of late Iron Age II pottery sherds in mixed fills, the earliest architectural remains revealed are simple dwellings dated to the Herodian period, specifically the first century CE, or perhaps even the late first century BCE. These houses appear to incorporate architectural elements and to have contained finds similar to those evidenced in contemporaneous Jerusalem residences, such as those of the Upper City, excavated in the Jewish and Armenian Quarters in the Old City and on Mount Zion. The houses had basements quarried in bedrock, covered with barrel-shaped stone vaults. Niches cut into the rock walls served as cupboards. The walls were occasionally plastered; in some cases the plaster was painted. Of the roughly 25 Second Temple period coins, all date to the first century CE, save for one Hasmonean coin. These findings may indicate that the eastern city wall, which has not yet been found, should be sought slightly to the east of this excavation area.

A flight of six roughly quarried steps, c. 3 m wide, ascend from the direction of the Gethsemane area northwest towards the Lion’s Gate. Later tomb shafts sever the steps. Indirect evidence suggests a Byzantine date for the staircase, apparently part of the staircase discovered in this area in 1890 by Petrie.

Approximately 30 tombs of the large Byzantine cemetery that extended along the eastern side of the city were encountered. They appear to have been concentrated along the route that connected the city with the Christian holy places on the Mount of Olives. The tombs were cut close to one another, resulting in occasional encroachments into previous tombs. Six Byzantine tombstones inscribed in Greek were found in secondary use as flagstones in a courtyard of an above structure. Excavations were carried out within only one of the tombs of the cemetery. It is a rock-cut burial cave accessed by a quarried shaft covered with stone slabs. Opposite the entrance and cut into its rock wall are several elongated burial troughs separated by low partitions. Several glass objects were found in the troughs.

Thick layers of grayish-brown earth, rubble, and debris were found overlying all of the Second Temple period and Byzantine remains. Among the debris were bricks, tiles, and pipes of the types used in bathhouse construction, indicating that a Byzantine bathhouse was located nearby. The entire area is also covered with a layer of black debris containing sherds from the Mameluke period and later.

RONNY REICH, ELI SHUKRON

9. THE GETHSEMANE FLOOD DIVERSION FACILITY

A flood diversion facility was unearthed in 1998 by J. Seligman and A. Re’em on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority just to the north of the Church of the Tomb of the Virgin Mary in the Kidron Valley. For centuries the church has endured floodwaters in winter, a problem which also, as it seems, beleaguered the church in the Crusader period. In that period, a vaulted structure, 32.90 m long and 5.90 m wide, was erected across the bottom of the Kidron Valley. It was founded in part on bedrock and in part on the alluvial soil accumulated at the bottom of the valley. Placed close to the apex of the inner side of the vault, which reached a height of at least 4 m, were 20 shafts, descending from the ground surface. The shaft openings were constructed of ashlars, some of which bear tooling marks characteristic of the Crusader period. Floodwaters poured through these shafts into the installation, which—on account of its well-plastered floor sloping toward the middle—directed the floodwaters to the center of the installation and then westward via a channel to an opening. This would have diverted the floodwaters around the church and then back into the Kidron Valley to its south.

10. BEIT ELIYAHU

A series of Mameluke period vaults supporting public structures was discovered in the Western Wall Tunnels. These vaults extend westwards, and one of the western vaults was found along the western side of ha-Gai Street (under Beit Eliyahu) by R. Abu Riya in 1991, north of the ha-Gai Street tunnel. The vaults are now sunken below the street level, only their tops protruding above this level. They reach a height of 6.20 m. The excavated vault, measuring 19.5 by 5.6 m, functioned as a pottery workshop. These structures were also in use in the Ottoman period; the floor level of the excavated vault was c. 2.5 m higher during this period. The excavated vault continued in use in various functions into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

DAN BAHAT

11. THE WESTERN WALL TUNNELS

Excavations have been conducted since 2000 beneath the Makhkama building, north of the prayer plaza at the western wall of the Temple Mount. The excavations have been directed by D. Bahat, on behalf of Bar-Ilan University. A group of vaulted rooms located in the foundations of the Makhkama building were cleared. At their core is a three-story building dated to the Crusader period on the basis of its architectural features and masonry dressing. Additions along its eastern and southern sides were constructed during the Ayyubid period. The Makhkama building was constructed over the entire complex in the Mameluke period.

Excavations reached a considerable depth below the white mosaic pavement of a room (no. 554) in the lower story of the Crusader building—a room abutting the so-called Herodian room to the south. Remains of earlier constructions belonging to several periods were uncovered. The earliest consist of small segments of floors from the end of the First Temple period (the eighth to early sixth centuries BCE), to which a wall consisting of several masonry courses laid as headers should perhaps also be attributed. The lower portion of a built and plastered mikveh with a wide flight of stairs descending from west to east was uncovered. The mikveh is assigned to the Hasmonean period (the early to mid-first century BCE); it was blocked with earth fills during the Herodian period, which raised the ground surface in this area by approximately 4 m.

A deep, plastered drainage channel was constructed in this area during the Herodian period (end of the first century BCE). The channel extends along the northern, eastern, and southern walls of the Crusader room. It is a branch of the drainage system constructed in the Tyropoeon Valley, passing beneath the street constructed in Herod’s time along the western wall of the Temple Mount, and conveying water eastward.

A public latrine from the Late Roman period (second–third centuries

12. THE STREET OF THE CHAIN

In the early 1990s, a number of limited excavations were conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority along the eastern side of the Street of the Chain (ha-Shalshelet St.) and in the plaza that separates the street from the Gate of the Chain, in the western wall of the Temple Mount. At a depth of approximately 1–2 m beneath the present surface of the Street of the Chain were found remains of the pavement of an early west–east street leading toward the Temple Mount. It consisted of large carefully laid square stones, 0.3–0.4 m thick, the largest measuring 2 by 1 m.

The westernmost portion of this pavement was excavated by R. Abu Riya at the junction of the Street of the Chain and the staircase descending to el-Wad Street. Two of the pavers bore a row of widthwise grooves. Found in the bedding of the pavement were a few sherds dating to the Late Roman period, apparently the second century CE. On the southern side of this exposed segment of the pavement is a water channel in which Late Roman period pottery was also found.

An additional segment of the pavement was revealed by L. Gershuny in an area abutting the eastern edge of Abu Riya’s excavation area. Beneath this segment was found the apex of one vault in the line of vaults extending westward from Wilson’s Arch. The pottery found beneath the pavement in this spot dates to the first century CE. The vault and the pavement above it thus appear to date to the Second Temple period.

E. Kogan-Zehavi revealed another segment of the pavement at the easternmost end of the Street of the Chain, at the entrance to the plaza in front of the Gate of the Chain. Beneath the pavement were found the tops of vaults. Kogan-Zehavi dates this segment to the Roman period; repairs to its southern part were dated to the Byzantine–Early Islamic period.

In L. Gershuny’s excavations in the plaza in front of the Gate of the Chain was found a stone surface that covers the top of Wilson’s Arch, which abuts the western wall of the Temple Mount. A 10.5-by-6-m segment of a staircase that ascends from west to east was uncovered in E. Kogan-Zehavi’s excavation at the western edge of the plaza in front of the Gate of the Chain. The construction consists of stones of various sizes and is constructed upon Wilson’s Arch. In the southern portion of the paved segment is the square foundation of a now missing column. A staircase ascending from west to east is located in this spot. It consists of two narrow steps (0.4 m wide) and one broad step (2.0 m wide), all 0.2 m high. The style of construction is similar to that of the Herodian period staircase at the entrance to the Huldah Gates. It is clearly part of an ancient staircase that rose from the eastern edge of the ancient Street of the Chain to the gate leading onto the Temple Mount. The excavator dates it to the Herodian period.

During the Early Islamic period, the staircase was narrowed on its northern side by the construction of a long curbstone and on its southern side by a long wall that served as a curbstone. The wall was built along the line of the column base of the previous period. South of the square column base was found the top of a vault constructed during the Umayyad period, north of Wilson’s Arch.

13. OHEL YIẒḤAQ

Excavations by the Israel Antiquities Authority in the Ohel

A segment of pavement of the Secondary Cardo dating to the Byzantine period was uncovered. The flagstones were laid diagonal to the axis of the street, which runs from north to south along the Tyropoeon Valley. Some of the paving stones with carved grooves were laid in other directions, indicating a repair. Additional segments of this street have been found to the north, along the line of present-day el-Wad Street, and to the south, west of the Dung Gate (see above). At the end of the Byzantine period or beginning of the Early Islamic period a building was erected flanking the street from the east; its entrance from the street was blocked in a later phase. At some point in the Early Islamic period a wall was constructed upon the pavement of the street, narrowing it. In the Crusader period, part of a room and a pool uncovered on the eastern side of the street were built. The room opened onto the street, and was apparently a shop or workshop; at some later stage, no later than the fourteenth century CE, the entrance to the room was blocked. South of this structure were found remains of another room with a stone floor and a blocked opening.

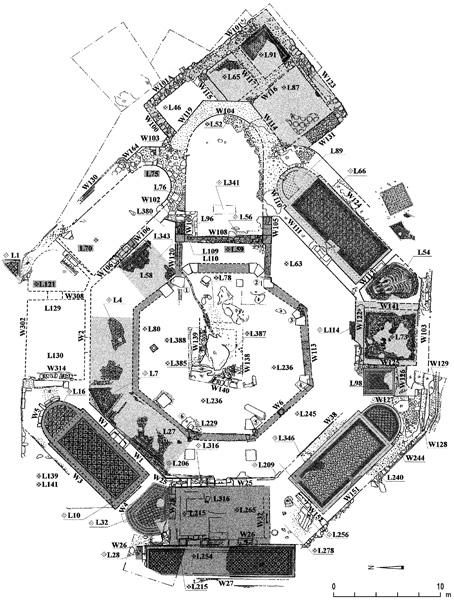

A bathhouse from the Mameluke period was found covering the entire excavation area. The building was preserved almost in its entirety, including its western façade, with its entrance flanked by stone benches. The bathhouse included a changing room, an octagonal hot room, small rooms to the west and east of the hot room, warm dry rooms at the center of the building, and an additional room on the eastern side of the building, with a dome decorated in molded plaster. The bathhouse heating system consisted of channels and pipes. This network was connected to a furnace room shared by an adjacent Mameluke period bathhouse referred to as Hammam el-‘Ain.

14. THE SOUTHEASTERN SLOPE OF MOUNT ZION

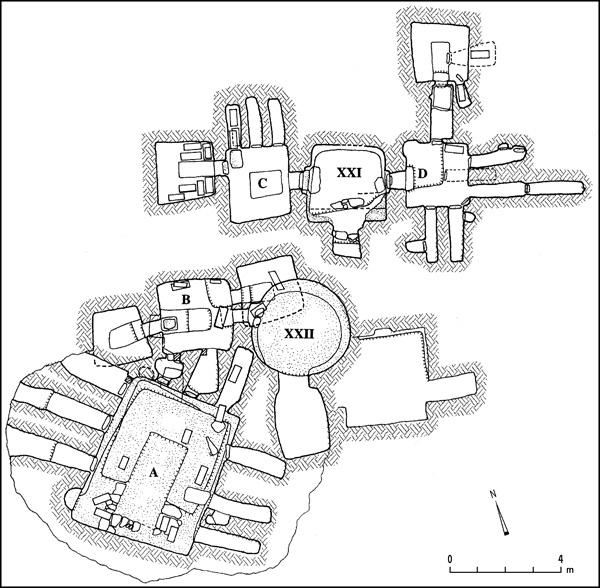

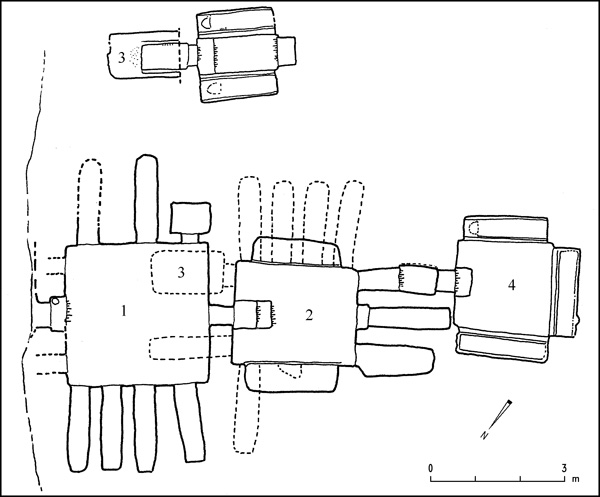

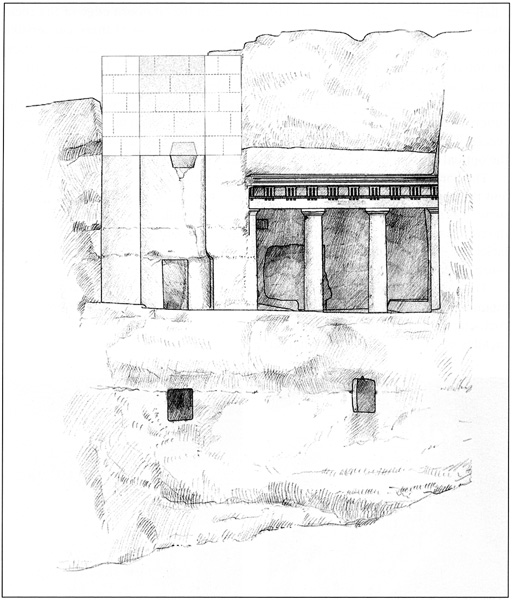

During 2005–2006, an excavation was conducted on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority by Z. Greenhut just above the meeting point of the Central and Kidron Valleys, a short distance to the west of the Pool of Siloam. The excavation area is bordered by a terraced quarried cliff that rises 13 m above its surroundings, with remains of a series of rock-hewn rooms arranged in three stories to the full height of the cliff. Little remains of the outer, stone-built walls of the rooms, but the plan of the structure of which they are apart can be reconstructed. Leveled rock surfaces served as the floors of the various rooms in this structure. The remains were found covered with earth dumps containing mixed pottery sherds dated to the end of the First Temple (eighth to early sixth centuries BCE), Second Temple (first centuries BCE and

Only stepped floors remain of the upper story of the structure. At least three rooms belong to the middle story. The rock cliff served as their western side and provides evidence that the rooms were vaulted or roofed with wooden beams. From the lower story, two rooms were entirely exposed and another two only partially. A dressed, framed opening located in the northern room leads to a natural cavity, apparently a storage area. There was evidence in another room of a white stucco paneled decoration. On the western side of the room, a niche that served as a cupboard was cut with an arched ceiling and covered with white plaster. At the sides of the niche are evenly spaced grooves that supported wooden shelves. Another room leads via a narrow, rock-cut, L-shaped staircase to the basement. In the northeastern corner of the structure were a plastered ritual bath (mikveh) next to a plastered reservoir (otzar).

The remains exposed attest to the existence of a terraced architectural complex that was erected during the Second Temple period (first centuries BCE–CE) at the bottom of the southeastern slope of the southwestern hill, opposite the Pool of Siloam. It illustrates the intensive settlement and high standard of housing in this part of Jerusalem at the end of the Second Temple period.

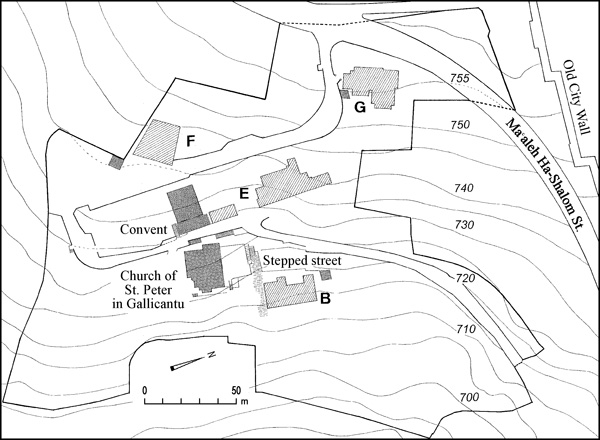

15. THE CHURCH OF ST. PETER IN GALLICANTU

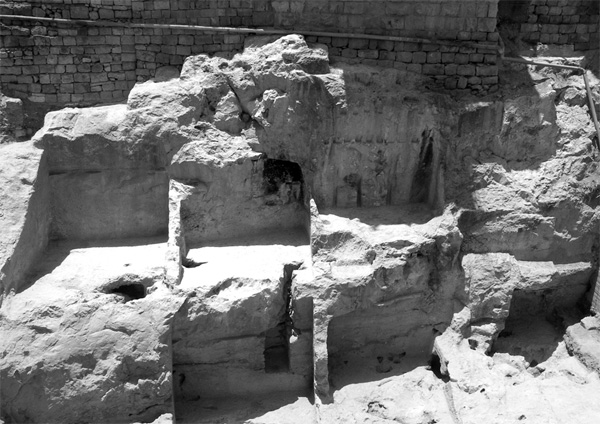

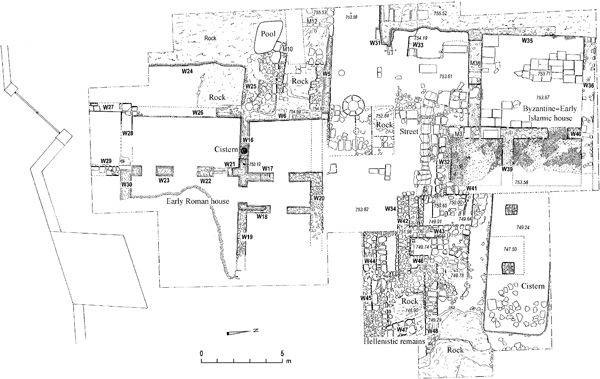

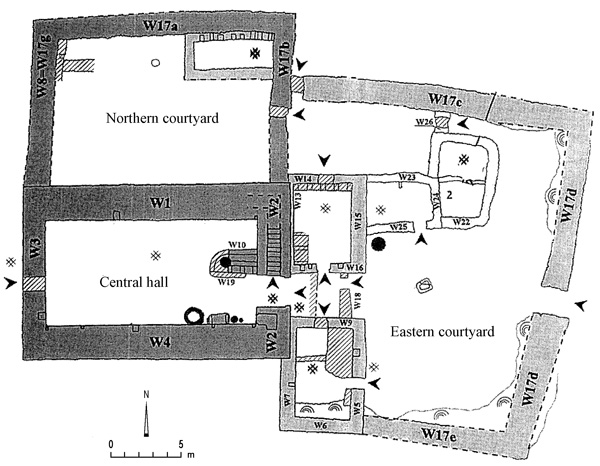

The excavations in the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu, on the eastern slope of Mount Zion, were conducted from 1992 to 2000. The excavations were carried out by the Instituto Español Bíblico y Arqueológico under the direction of F. Díez, and in some of the excavation seasons, jointly with I. Prieto and J. Campos. Areas B, E, F, and G were excavated in the vicinity of the church. Remains dating from the end of the Hellenistic period to the Early Islamic period were encountered. In general, the remains were found in an extremely poor state of preservation due to extensive robbery of building stones, beginning mainly at the end of the Early Islamic period.

A mikveh and five rock-cut cisterns from the Second Temple period were found in area B; two of the cisterns were reused in the Byzantine period. Part of a stone-paved Byzantine street with a rock-cut channel under its paving stones was also excavated in this area. It extends from north to south, toward the stepped street uncovered by J. Germer-Durand, which ascends from the City of David to Mount Zion.

Exposed in area E were a cistern, pool, and the remains of a building with thick walls, all dated to the Second Temple period. Byzantine period remains in the area include two rooms of a building, one paved in a geometric mosaic consisting of squares and hexagons, the other in white mosaic. There is also a very well-constructed Byzantine channel, descending from north to south, preserved only in the northern end of the excavated area. A short section of an Islamic, probably Mameluke, pipe aqueduct was uncovered; it was constructed within the low-level aqueduct of the Second Temple period. Because area E was very disturbed, the remains of two fragments of walls, 1.80 and 2.00 m thick, respectively, could not be dated. One is oriented east–west and should probably be attributed to the pre-Herodian period. The other is oriented southwest–northeast. These walls display different types of construction and do not belong to the same structure.

First Temple period (eighth–early sixth-century BCE) remains of a wall were uncovered in area F. Byzantine period remains include portions of walls and a mosaic floor with multicolored geometric designs. A unique find is a pottery jug containing a hoard of Byzantine gold coins of the sixth–seventh centuries CE. Also apparently dated to this period are the remains of another building, including portions of walls, white mosaic floors, a pavement of stone slabs, and probably a courtyard or square in which the capstone of a cistern was found in situ. In one of the rooms of this structure were found small pools and channels, apparently suggestive of an industrial installation.

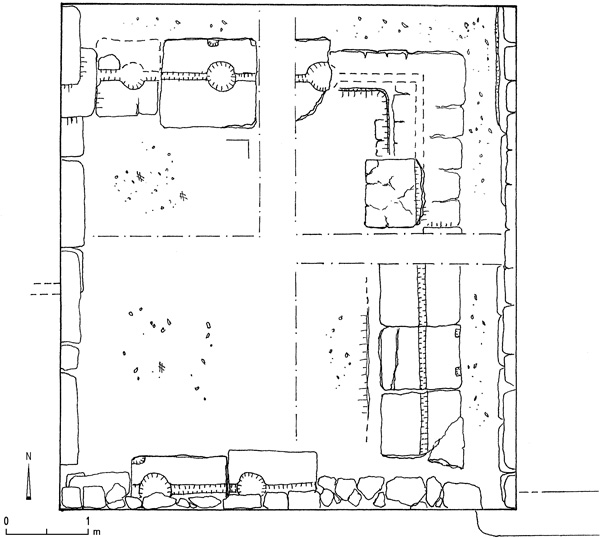

Uncovered in area G were the remains of a mansion of the first century CE. It includes an inner courtyard surrounded by rooms with plastered floors and painted, stuccoed walls. Retrieved from inside the building were collapsed stones and various Second Temple period artifacts that attest to its destruction in 70 CE. On the eastern side of this excavation area, portions of additional Second Temple period buildings were uncovered, including the remains of Late Hellenistic period walls constructed on bedrock and a large rectangular cistern with internal pillars that had supported a now-collapsed vault. The cistern was filled with debris including abundant sherds dating to the end of the Second Temple period. A Byzantine period structure that remained in use through the Early Islamic period was also uncovered. Three of its rooms had mosaic pavements, those of the two smaller rooms bearing colored geometric decorations and small crosses. In the larger room, the mosaic was replaced in a later phase by paving stones.

16. THE ḤURVAH SYNAGOGUE COMPOUND

Excavations in the

The earliest remains were portions of walls and gravelly earth fills of the Iron Age II (eighth–early sixth centuries BCE) uncovered on the northeastern side of the excavation area. At the center of the area was a square installation (1.2 by 1.2 m, 1 m deep) cut into bedrock.

Fragmentary remains of two construction phases dated to the late Second Temple period were found in the center of the excavation area. To the early phase, which is dated to the first century BCE, belongs a small, stepped, quarried mikveh. Part of the ceiling of the mikveh is cut into bedrock. It was intentionally blocked with earth and stones during the later phase, in the first century CE, when a building was constructed over it. Parts of two rooms and two mikvehs of the building were exposed. A rock-cut threshold of a doorway separates the two rooms. The eastern part of the earth floor of the western room lay upon a quarried bedrock surface, its western part over the blocked mikveh of the early building phase. The earth floor of the eastern room was laid upon an earth fill over shallow quarrying in the bedrock. Upon the floors of these rooms were fallen squared building stones and accumulations of earth, burnt beams, and sherds of partially restorable vessels. The remains of two poorly preserved mikvehs were discovered south and west of the rooms, but separated from them by later construction. All of these remains are part of a Herodian period residential structure dated to the first century CE. The finds indicate the destruction of the building by fire during the Roman conquest of Jerusalem in 70 CE, much like the evidence from the more impressive conflagration remains left in the Burnt House, also uncovered in the Jewish Quarter.

Remains of two segments of a stone pavement of the Byzantine period, totaling 10 m long and 3.7 m wide, were found on the southwestern part of the excavation area. The pavement is part of a sixth-century CE paved street that ascended from the Cardo eastward, toward the area today located at the center of the Jewish Quarter. It is identical in its details to that of the Cardo, which passes several meters west of the excavation area. The pavement rests directly upon a rock-cut surface between two quarried walls, which remain standing up to 1 m in places. It slopes slightly upward from west to east and consists of rows of large slabs of hard limestone, carefully trimmed and fitted, but very worn and cracked from extensive use. Along the northern side of the pavement is a massive wall (1.5 m wide) constructed on the quarried rock wall; it was built of roughly trimmed stones preserved in several places to six to eight courses. At the center of the exposed wall was a gap, evidence of an opening onto the street. Only a small portion of the wall on the opposite side of the street remained.

Part of a room from the Early Islamic period was found at the eastern edge of the excavation area. The western wall of the room is both quarried in bedrock and built of stone. The room has a simple white mosaic floor, the southern part of which was laid upon a quarried rock surface; the northern portion, where the bedrock is lower, was laid upon an earth fill. Portions of two jars dated to the eighth–ninth century CE were found buried upside-down beneath the floor in this part of the room.

During the Mameluke period, the paved Byzantine street went out of use and deposits of earth and stones reaching a depth of 2 m accumulated upon it. The eastern edge of the revealed segment of the street was destroyed during this period with the construction of a vaulted cistern. A square installation was uncovered north of the wall that bounded the street to the north. Quarried into the bedrock to a depth of 1 m, the installation was accessed by a narrow staircase leading down into it. Numerous finds dated to the twelfth–thirteenth centuries were retrieved from the earth fills upon the street and in the installation.

17. THE KISHLEH BUILDING

In 2000–2001, excavations were conducted by A. Re’em, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, within the Kishleh building, which is located just to the south of the Jerusalem Citadel. A sequence of archaeological remains from the Iron Age II to the Ayyubid period was uncovered in the foundations of the building.

Remains of walls and floors dated to the eighth to early sixth centuries BCE were found. The principal of these is a buttressed north–south wall, 15 m of which was uncovered. The wall is constructed of large, partially trimmed stones and was preserved to a height of 2.5–3.0 m; its width was not established. The nature of the wall’s construction, dimensions, and location at the western edge of the southwestern hill of ancient Jerusalem suggest that it is another part of the city wall that surrounded the hill during the First Temple period, remains of which have been found to the north in the Citadel and to the south in the Armenian Garden and on Mount Zion.

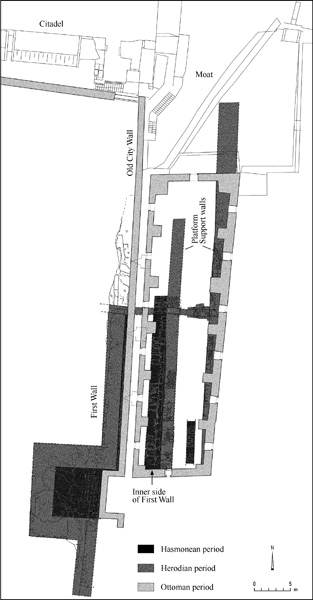

A 5-m-wide wall was found at the western edge of the excavation area. Its inner face is constructed of well-dressed stones with margins and a pronounced rough boss. Its outer face lies beneath the Ottoman Old City wall. It is another part of the First Wall of the Hasmonean period, portions of which have been exposed to the north in the Citadel and to the south along the western side of the southwestern hill.

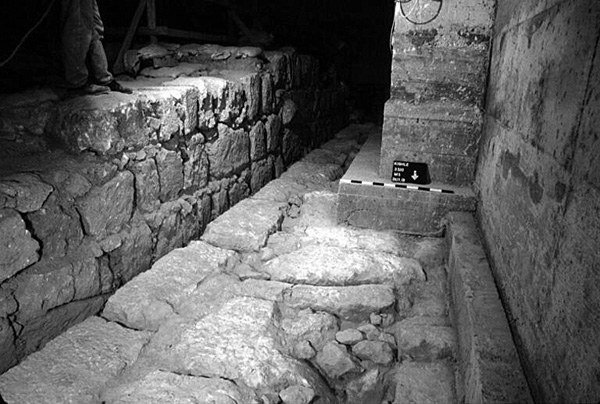

Two parallel walls running north–south along the entire length of the excavation area were uncovered, part of the platform on which Herod’s palace was constructed. The western wall is 1.8 m wide, preserved to a height of 4 m; the eastern is 3 m wide, preserved to a height of 7 m. The walls rest upon bedrock and are constructed of a combination of stones of various types, including ones in secondary use. The space between the walls is filled with leveled, compressed layers of earth. Abutting the eastern wall is a drainage channel covered with stone slabs that extends below the fortification line and to its west. Similar remains were encountered to the north, in the Citadel, and to the south, in the area of the Armenian Garden.

Portions of a twelfth–thirteenth-century CE wall incorporated into the Old City wall, and eight industrial pools of varying sizes and depths were also uncovered.

HILLEL GEVA

18. THE MAMILLAH AREA

The Mamillah area is located along the western side of the Old City wall, outside Jaffa Gate. It was first explored in 1887 by C. Schick, who reported the discovery of a solid wall running parallel to the Old City wall. In 1927 and 1935, the Mandatory Department of Antiquities excavated several Iron Age II tombs, later published by R. Amiran. In 1984, H. Goldfus exposed a small segment of C. Schick’s wall close to Jaffa Gate. Excavations were also conducted to the north of Jaffa Gate by A. Maeir (1989). The large-scale excavations in the Mamillah area were conducted by R. Reich and E. Shukron on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1989–1995.

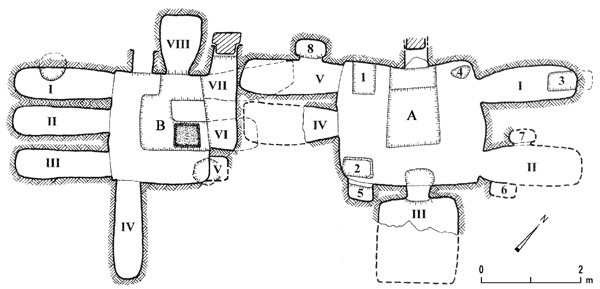

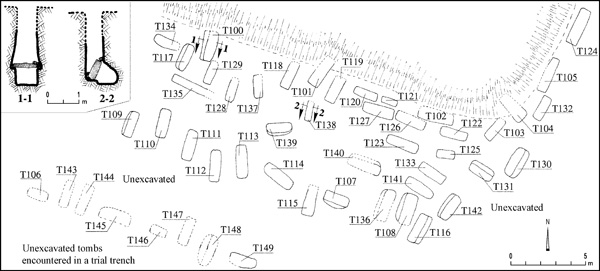

IRON AGE II TOMBS. The earliest remains in this area belong to a late Iron Age II (eighth to early sixth century BCE) cemetery. Most tombs were damaged by later Late Roman and Byzantine quarrying operations. Roughly ten were found to contain burial goods; some of these tombs were preserved in their entirety. The cemetery is clearly associated with the quarter newly founded in the eighth century BCE on the southwestern hill of the city.

Several of the tombs (nos. 5

Two of the late Iron Age tombs were reused in the period following the destruction of Iron Age Jerusalem. An assemblage of pottery vessels of the sixth century BCE, similar to that found in the tomb at Ketef Hinnom, was found in tomb 5. An assemblage of mid-fifth century BCE artifacts, including some cosmetic implements and an imported black Attic amphoriskos, was found in tomb 19. These finds show that a relatively small community remained in Jerusalem or in close proximity to it after the destruction and exile of 586 BCE.

HELLENISTIC PERIOD TOMBS. Several tombs of a type new to Jerusalem were excavated. The entrance to the tombs is via a vertical, rectangular shaft. At the bottom of the shafts are rock-cut loculi (kokhim). Such shaft tombs have one, two, or four loculi. A few artifacts are indicative of the second century BCE. This type of tomb appears to mark the first appearance of the loculi, which would become so common in Jerusalem burial caves of the first centuries BCE and CE.

LATE ROMAN DEBRIS. The area was covered with quarries from which medium-sized blocks of stone were extracted. These are difficult to date, but, since they cut through the Iron Age tombs, they clearly postdate the Iron Age. In addition, a large amount of debris covering the area contained broken roof tiles and bricks bearing the impressed insignia of the Tenth Roman Legion, which was garrisoned in the city.

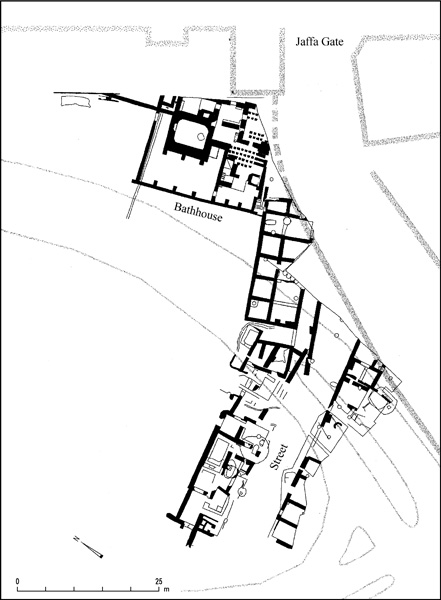

A BYZANTINE PERIOD EXTRA-MURAL QUARTER. The most intensive activity in this area took place during the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods. It is assumed to have been extra-mural in those periods, as small segments of the contemporaneous city wall have been uncovered in the Citadel. The location of the Byzantine western city gate of Jerusalem can be inferred from the discovery of an extra-mural street leading to it in the excavation area, c. 20 m south of Jaffa Gate. This street was flanked on both sides by elongated blocks of buildings constructed on terraces descending outward from the center of the city. The buildings were divided into uniform units containing a variety of installations; they may have been shops. The buildings on the northern side of the street, facing south, had a roofed gallery shading the sidewalk; those on the southern side of the street would have enjoyed natural shade.

The excavations by A. Maeir exposed another street leading northwest from Jaffa Gate, with an elongated building flanking it to the east. The rooms of the building were used as shops. The small finds they yielded suggest that pilgrims purchased merchandise in them. These finds include a marble slab with an Armenian inscription, a miniature pottery flask originating in Asia Minor, and a small cruciform bronze pendant with a wood inlay. Further to the west was another elongated building which might have served as lodging for pilgrims. Mosaic floors there bore Greek versions of Psalms 95:6 and 118:6–7.

The ruins of a bathhouse are located directly below the Ottoman Jaffa Gate and the Ayyubid city wall. The location of this establishment in the public area near the gate, the street, and the shops was carefully chosen. It is also situated near and slightly lower than the adjacent aqueduct that entered the city nearby. The aqueduct likely supplied water to the bathhouse.

The remains of this aqueduct, constructed to carry water from Birkat Mamillah (700 m west of Jaffa Gate) to Birkat Hammam el-Batraq (the so-called Hezekiah’s Pool, within the Old City near Jaffa Gate) was partially exposed along Mamillah Street by A. Maeir, R. Reich, and E. Shukron, and later by Y. Billig and E. Assaf. The aqueduct is a 0.7-m-deep and 0.4-m-wide channel resting on a low wall. It entered the city roughly 50 m northwest of Jaffa Gate. Open areas were left on either side of it. It was in use from the Byzantine period to the end of the nineteenth century. No conclusive evidence for a Roman aqueduct has yet been found in this area.

A BYZANTINE PERIOD CRYPT. A cemetery situated roughly 100 m west of Jaffa Gate contained simple inhumations, distinct from the many built or rock-cut tombs of this period encountered around the city, particularly on its eastern side. Exceptional is tomb 10, a natural burial cave from the Byzantine period that contained an extremely large quantity of human bones piled in apparent disarray. A simple chapel stood in front of it. The tiny apse is adorned with a wall painting representing the Annunciation, only the angel of which has survived. The mosaic floor bears a Greek inscription in tabula ansata: “for the salvation and succor of those whose names only the Lord knows.” The few artifacts found among the bones were several cross-pendants of stone and bronze, indicating that the interred individuals were Christian. The latest of the c. 130 coins found in the crypt is a gold coin minted under Phocas (602–610

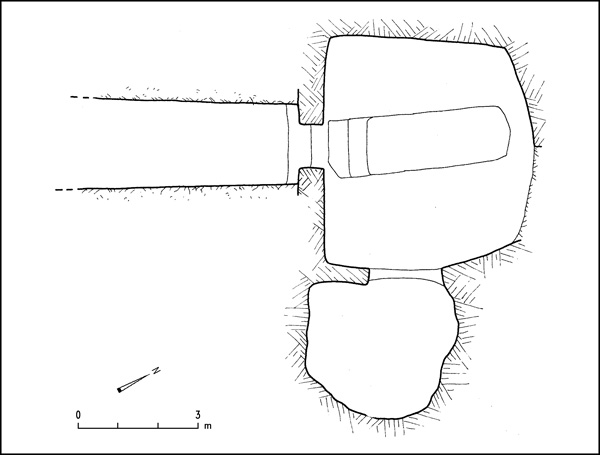

AN AYYUBID FORTIFICATION. The latest architectural feature discovered in this area is a fortification line located parallel to the Old City wall, roughly 6.25 m to its west. Approximately 110 m of the wall has been exposed, extending northwest of the Jaffa Gate. Part of this segment survives as masonry courses, while farther to the north only the lower, rock-cut foundation has survived. The width of this wall could be established in only one spot, where it measures c. 3.20 m. Next to Jaffa Gate the wall was largely constructed upon the remains of the Byzantine period bathhouse. At the northwestern edge of the excavated segment of the wall, the slightly inclined, rock-hewn base of a protruding tower, up to 3.3 m high, was exposed. At the point where the wall and tower meet, a rock-cut staircase descends from the tower to the rock surface just outside of it. The staircase probably led to a small postern, which has not survived.

The builders of the wall appear to have reused stones from various sources in its construction. The large stone collapse found along the line of the wall included some dressed stones, stones with mason marks, and stones bearing traces of a polychrome wall painting, probably from a destroyed Crusader church. One piece depicts the head of a young Madonna wearing a head shawl, clearly indicating that the builders of the wall utilized building materials salvaged from a nearby Crusader church in constructing their fortifications.

The stratigraphic positioning of the wall over a Byzantine bathhouse and below the foundations of the Ottoman Jaffa Gate, the thirteenth–fourteenth century pottery found in the earthen layer that covers the stone collapse, the reuse of Crusader masonry in the wall, and a coin of al-Malik al-Kamil Nasir ad-Din al-Ma’ali Muhammad (1211–1237

RONNY REICH

19. THE HEROD’S GATE AREA

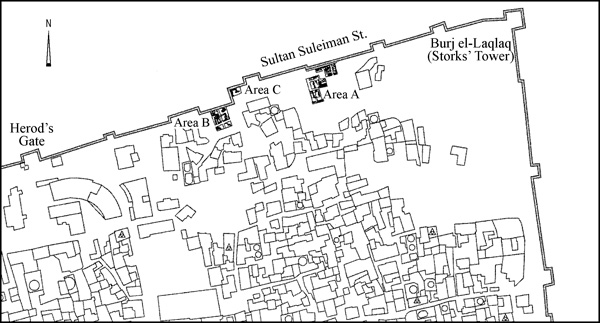

Excavations in the area of Herod’s Gate were conducted in the years 1998, 2001, and 2004–2005 by Y. Baruch, G. Avni, and G. Parnos, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The excavated area totals 600 sq m, and is situated adjacent to the northeastern corner of the Old City of Jerusalem and within the city wall, c. 120 m east of Herod’s Gate. Since the beginning of the Ottoman period, this area had been an open field known as Burj el-Laqlaq (the Storks’ Tower), after the northwestern tower of the Old City wall. In photographs and maps of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the area within the walls east of Herod’s Gate appears mainly as agricultural plots.

The excavations, which reached bedrock in most places, indicate that the bedrock in this area gently slopes from east to west toward a wadi bed known in the Second Temple period as the Bezetha Valley, which begins west of the Rockefeller Museum and descends to the Kidron Valley north of the Temple Mount. It appears that the wadi filled with debris over the years, a result of building activities. The excavations were conducted in three areas—A, B, and C—all abutting the Old City wall. Several settlement strata were distinguished, dating from the First Temple period (Iron Age II) to the end of the Ottoman period.

FIRST TEMPLE AND HELLENISTIC PERIOD FINDS. The finds from the First Temple period (eighth–sixth centuries BCE) were encountered in area A. They include pottery, such as a jar handle bearing a lamelekh seal impression of the single-wing type. No architectural remains were uncovered. The finds appear to be related to activity outside the walls of Jerusalem at the end of that period, evidenced generally by quarries, rock-cut burial caves, and pottery. Retrieved together with the Iron Age pottery were Hellenistic period finds, including two seal-impressed Rhodian jar handles and a number of Hasmonean period coins. Layers from this period covered an area of ashlar quarries extending northward.

LATE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD BUILDINGS. Most of the late Second Temple period remains were found in area A. They include stone walls preserved up to 1.50 m in height, apparently related to the expansion of Jerusalem beyond the line of the First and Second Walls and the construction of the “new city” in this vicinity, referred to by Josephus (War V, 142–162). The buildings exposed in area A were built upon stone terraces. On the uppermost terrace was exposed the outer face of a 6-m-long wall segment (wall 1062) belonging to a building erected upon the earlier stone quarries. The wall is constructed of carefully trimmed stones laid as headers and stretchers.

In the western part of area A, upon the lower stone terrace, was exposed a portion of a structure (building 1000) with massive walls (c. 1 m thick) constructed of large stones, roughly trimmed on their outer face. This building appears to extend northward beyond the line of the later walls constructed over it. Within the building were found a thick layer (c. 1.8 m) of pottery sherds and whole vessels. Two trenches excavated within this fill yielded hundreds of sherds of a variety of vessels, primarily cooking pots and thin bowls, dated to the end of the Second Temple period. An inscription in black ink in typical Second Temple period Hebrew script reading smq’ was found on one of the jar sherds, apparently indicating the contents of the container, perhaps a type of red wine. Sherds of stone vessels typical of the period and several coins of the first century CE were also found. Many of the cooking vessel sherds had small holes pierced in their sides. Perforated cooking pots are known from other excavations in Jerusalem, such as at the City of David, near the Temple Mount, and in the Jewish Quarter. One theory for this phenomenon is that the hole disqualified the vessel as a container, thus dissolving it of its ritual impurity if it had been exposed to some defiling element, as written in the Mishnah (Kelim 2, 3). Earth fills and floors containing more sherds of the same period were associated with the walls of this building.

LATE ROMAN PERIOD FINDS. This area of the city appears to have been abandoned following the Roman conquest in 70 CE. In area A, layers with a few sherds dated to the Late Roman period were found upon the walls of building 1000. On the eastern terrace in this area, a typical second–third century CE cooking pot containing remains of ash and animal bones was found inside a pit lined with flat stones, which had severed a Second Temple period wall (wall 1062). Also found in this pit were earth fills containing copious amounts of Roman sherds and roof tiles bearing stamps of the Tenth Roman Legion.

THE “ROMAN–BYZANTINE” CITY WALL. In area B, a segment of the so-called Roman–Byzantine city wall was found directly below the Old City wall. The segment of wall exposed is constructed of square, smoothed ashlars. Some of these are typical Herodian building stones in secondary use. Nine courses of this portion of the wall have been preserved, reaching a height of c. 5 m. The seven lower courses were constructed as receding courses, giving the inner face of the wall a stepped appearance. The earth fills associated with the line of the wall slope southward. They appear to be intentional fills deposited in two different periods: the first at the time of the construction of the wall, as it contained third–fifth century CE pottery; and the second in the second half of the sixth century CE.

Area A was excavated down to the base of the Old City wall, but no remains of the city wall encountered in area B were encountered. Nor is there any indication of the wall from this point up to the northeastern corner of the Old City wall. This probably indicates that the Roman–Byzantine city wall of Jerusalem did not extend to the northeastern corner of the Old City, but turned southward at a sharp angle and extended along the Bezetha Valley before joining up with what is now the eastern line of the Old City wall at some point along the eastern wall of the Temple Mount.

The wall discovered in area B remained in use throughout the Byzantine period. In area A, an earth fill, floors, and segments of poorly constructed walls of an unclear plan were associated with the line of the city wall. Fills containing considerable quantities of white tesserae and tesserae production waste attest to this having been a production site for mosaic tiles.

AN EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD FORTIFICATION AND QUARTER. The principal Early Islamic period remains were exposed in area A, where a massive wall was revealed directly beneath and along the course of the Old City wall. It is built of roughly shaped stones and is of entirely different construction than the Roman–Byzantine wall found in area B. Additional segments of the wall were exposed in area C. Also exposed in area C were carefully carved, profiled masonry stones—perhaps part of a gate that once stood in this area—among a stone collapse. The pottery found within this collapse, like that of the earth fill associated with segments of the wall found in area A, is dated to the end of the Early Islamic period (tenth–eleventh centuries

Uncovered south of this wall were fragmentary walls of buildings, apparently part of a dense residential quarter showing no evidence of advance planning. The walls are simple constructions of small stones bonded with clay. The floors are of tamped chalk. These remains date from the end of the Byzantine period and remained in use, with modifications, at least until the eleventh century CE.

CRUSADER AND AYYUBID PERIOD FORTIFICATIONS. Based upon detailed historical descriptions of the Crusader conquest, it was in this area of the city that the Crusaders broke through the walls of Jerusalem on July 15, 1099. Actual evidence for the line of the city wall of Jerusalem during the Middle Ages was found in the excavation next to the Old City wall in areas A and C. The abovementioned Early Islamic period wall was buttressed by a fortification preserved as a row of piers. Another wall was found to extend 25 m from the remains of the massive piers southward. Earth fills containing numerous iron arrowheads were associated with the remains of the wall with piers. A survey in the vicinity of the site, carried out during the excavation, revealed another wall, perpendicular to the line of the Old City wall, some 20 m east of area A. Its visible length upon the surface was 11 m, its width 2.8 m, and its preservation height 2 m above the surface. Another wall with similar characteristics and also clearly related to the line of the Old City wall was surveyed at a distance of c. 10 m from area B. Associated with it on the east is a building with a roofing system of pointed arches resting upon ashlar piers. The piers bear diagonal stonecutting marks typical of the Middle Ages. The remains noted appear to constitute part of a single fortification system, the precise nature of which has not yet been established.

MAMELUKE PERIOD BUILDINGS. The findings in area B suggest that the city wall of the Early Islamic and medieval periods was in a poor state by the Mameluke period, perhaps even partly in ruins. Some of its stones were probably utilized to construct the private dwellings built adjacent to and abutting the city wall. Historical sources, such as the description by Mujir ad-Din (1495) and Mameluke period maps, show that much of the walls of Jerusalem were derelict under Mameluke rule. Only upon the reconstruction of the city wall at the beginning of the Ottoman period did this area once again become a fortified part of the city.

Remains of private construction of the Mameluke period were uncovered in the excavation. In area A, a building whose walls rest upon those of Early Islamic and Second Temple period buildings was partly uncovered. It was mostly constructed of stones in secondary use. In its southern wall was a doorway that led to an open area. Two phases were found in its floor; the bottom floor was of coarsely crushed chalk, the upper floor of plaster painted bright red. The building was severed during the Mameluke period by a broad trench and deep pits sunk to bedrock. The trench was filled with deposits containing abundant finds dated to the Mameluke period.

Another building was excavated in area B, next to the line of the Old City wall. Its walls were constructed of stones in secondary use, consisting both of typical Herodian masonry and stones taken from the Roman–Byzantine city wall. An unroofed courtyard was constructed north of the building; at its center was a deep cistern. Beneath the house was a room with a vaulted roof supported by ashlar corner piers, probably the ground floor of the structure, but possibly the remains of an earlier building.

THE OLD CITY WALL AND OTHER REMAINS. The Old City wall was constructed during the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in 1535–1538. A broad trench was dug prior to construction, apparently along many portions of the earlier fortification line. As a result, the Mameluke building in area B was destroyed. The fill in the trench included large amounts of stone cutting debris, undoubtedly related to the construction of the wall itself. South of the wall were exposed the remains of Mameluke and perhaps earlier buildings, which were used during the Ottoman period. Among the numerous artifacts found in these buildings were coffee cups and clay pipes.

YUVAL BARUCH, GIDEON AVNI, GIORA PARNOS

20. THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY SEPULCHER

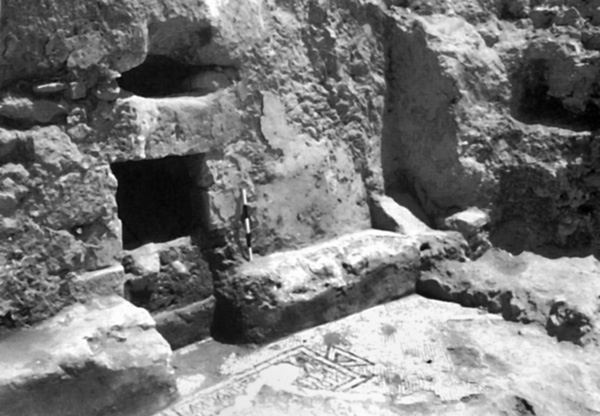

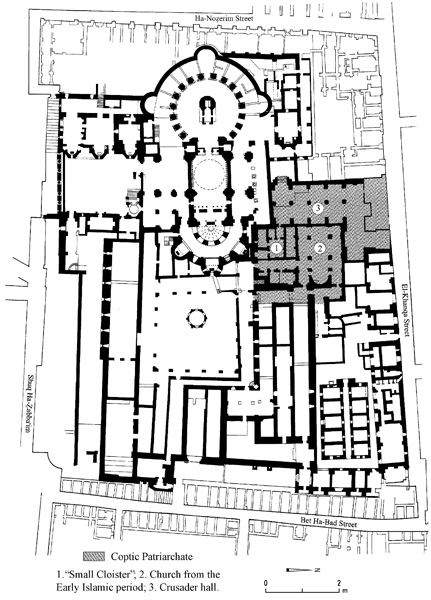

An excavation was conducted in 1997 by G. Avni and J. Seligman, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, within the confines of the Coptic Patriarchate in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Three structures incorporated into a Crusader (twelfth-century) monastery were revealed. One was already known from previous probes in the church as the Small Cloister—a small courtyard surrounded by a colonnade, as was customary in Europe in the Middle Ages. Its architectural character suggests that it was part of the monastery complex, perhaps used by Augustine monks who served at the church. Another structure excavated is a large hall (c. 31 by 13 m), datable by its building style to the Crusader period. It includes ten bays, and was described in previous surveys as a hospital within the monastery complex. Some of the bays were used as garbage pits for the shops along the adjacent

21. THE NORTHWESTERN CORNER OF THE OLD CITY

In 1999–2000, segments of fortification remains of various periods were found in the northwestern corner of the Old City during excavations under the direction of S. Weksler-Bdolah, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The remains can be quite well associated with the fortifications uncovered in the area in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries both inside and outside the Old City walls. The excavations were conducted in a small area (8.00 by 3.00 m), but are nevertheless instructive on the city’s fortification sequence over its various periods.

The earliest stratum revealed dates from the Byzantine period; only a floor with a drainage conduit survives from it. Other structures of this period located here were severed by the Ayyubid tower (see below), so that it is impossible to ascertain the nature of the Byzantine buildings in this spot. In light of the finds from the adjacent Knight’s Palace Hotel, it can be established that this area of the Old City was also enclosed within the so-called Roman–Byzantine city wall, which did not, as it has been suggested, follow a course farther to the east. The stratum above the Byzantine remains can be chronologically associated with the lowest course of the city wall (from the ninth century CE and slightly later), which was revealed under the Old City wall in this area. Subsequently, the entire area was covered in earth fills, leading to the conclusion that it was not resettled until the Crusader period. (It is recalled that found nearby was a massive tower, datable to the Fatimid period, perhaps the Tancred Tower mentioned in documents from the Crusader period.)

The next stratum consists of an Ayyubid tower (twelfth or beginning of thirteenth century