Ramat ha-Nadiv

INTRODUCTION

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE IRON AGE (STRATUM V). Roughly 140 Iron Age sherds were retrieved, most dating to the Iron Age I, in mixed loci at the top of the hill (area C), in the vicinity of the spring (area A), and on the eastern slope of the hill. A scarab dated to the beginning of the Iron Age was also recovered. It appears that Ramat ha-Nadiv belonged to the Dor district mentioned in the Bible (1 Kg. 4:11).

THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD (STRATUM IV). The Early Roman period builders seem to have incorporated the remains of Hellenistic walls into the foundations of buildings they constructed at the site. Segments of about a dozen of these walls were found scattered over a roughly 0.25-a. area atop the hill. Pottery from this period includes a rich variety of jars and cooking vessels, as well as imports, primarily from Greece and the Aegean. Most of the coins from this period were third-century BCE Ptolemaic issues. Unearthed near the spring was a circular pool (diameter 2.5 m) severed by a Herodian aqueduct, suggesting that it was constructed in an earlier period, perhaps the Hellenistic period. The Hellenistic settlement was apparently destroyed during Alexander Jannaeus’ conquest (104–76 BCE) and the site was abandoned until Herod’s reign.

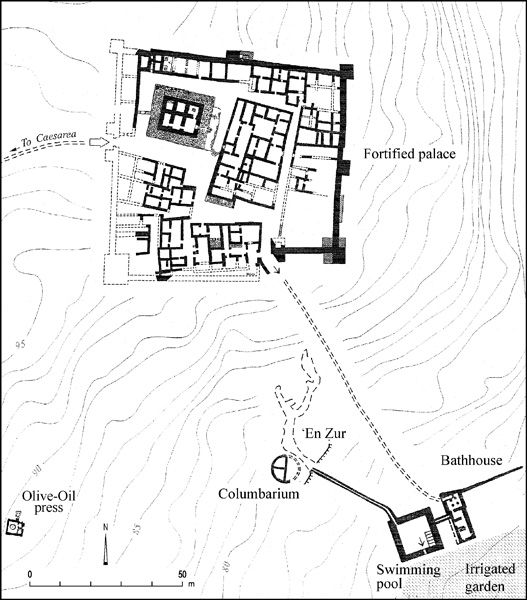

THE EARLY ROMAN PERIOD (STRATUM III). Remains of the Early Roman period include a palatial complex atop the hill (area C); and a water tunnel, aqueduct, pool, bathhouse, columbarium, and olive-oil press at the base of the hill, in the vicinity of the spring. Rich numismatic finds, imported pottery and glass, and bronze and marble artifacts attest to the wealth of the owner of the structure, as does the site’s commanding position overlooking the Nadiv Valley and the water sources of Caesarea (the Shuni springs). The palatial complex was abandoned during the First Jewish Revolt and the site remained unoccupied until the renewal of settlement at the end of the Ottoman period.

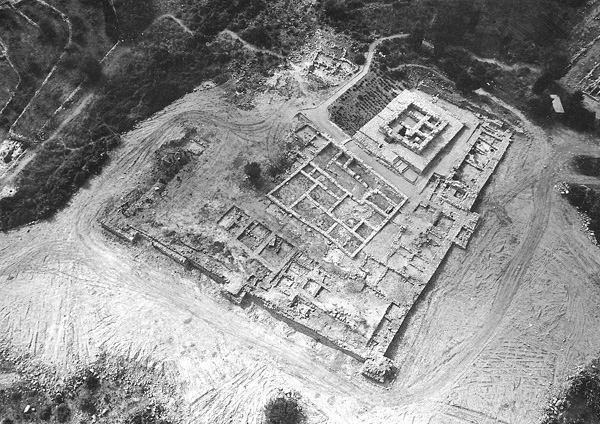

Remains atop the Hill. The complex atop the hill is a square fortified structure with four corner towers, thus appearing to have been a tetrapyrgion. Josephus mentions a tetrapyrgion-type palace twice: once in his description of the palace of Demetrius I Soter (162–150 BCE) near Antioch and once in his description of Herod’s palace at Masada (War VII, 289). The tetrapyrgion at

The large tower, apparently associated with the main gate, is located on the western side of the complex. It is a large structure, 13.3 by 11.5 m, with 1.4-m-wide ashlar walls. The tower is surrounded by a 3-m-thick outer wall, intended to protect its foundations and strengthen its walls. A flight of stairs ascends to its entrance on the east. There was a cistern next to the stairs, in front of the entrance, for the storage of drinking water for the inhabitants of the tower. The interior of the tower is divided into six rooms. A basement story was exposed 2 m below the floor of the southern room, containing dozens of jars in situ. In the northeastern room of the tower was found a central pier that served as a support for a wooden spiral staircase leading to the upper stories. In the northwestern room was a plastered bathroom.

A street runs between the tower and the living quarters to its east. At the southern end of the street was found the threshold of a gate, 3.1 m wide, making it possible to separate the tower from the other parts of the complex. The two outer threshold stones were engraved with alphas, apparently against the evil eye. The living quarters in the center of the enclosure include some 30 rooms of various sizes, constructed in a single unit measuring c. 30 by 20 m. At the center of the structure is a small inner courtyard with a cooking installation. Upon the floors of the rooms were found a variety of domestic artifacts including grindstones, crushing stones, jars, cooking pots, and spindle whorls, indicating that this wing served as living quarters for the servants and staff of the complex. The inner northern and eastern wings abut the enclosure wall.

An elaborate residential wing or villa, 35 by 20 m, was exposed in the southern part of the complex. Finds from the excavation of this unit include carved architectural elements, as well as the upper portion of a marble table leg carved in the form of a lion’s head, originally part of a round marble table with three legs. An examination of the marble indicates a provenance on the island of Thassos in the southern Aegean. These finds, as well as many rich artifacts such as gold jewelry, imported vessels, and marble pavement, are evidence that the living quarters were utilized by the owner of the palace and his family. Stone vessels of the Jerusalemite type attest that the owners of the palace belonged to the Jewish upper class of Judea.

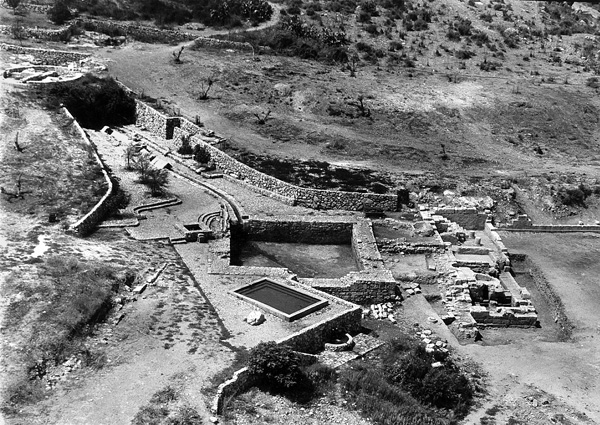

The Remains near ‘En

A large pool was exposed at the end of the aqueduct. It is square (11.2 by 11.2 m) and its total capacity is 300 cu m; its walls are 1.8 m thick and are lined with a layer of gray hydraulic plaster typical of the Herodian period. A layer of reddish plaster characteristic of the Byzantine period over the Herodian plaster indicates continued use of the spring complex in Byzantine times. A 1.2-m-wide corner staircase provided comfortable access to the bathing pool.

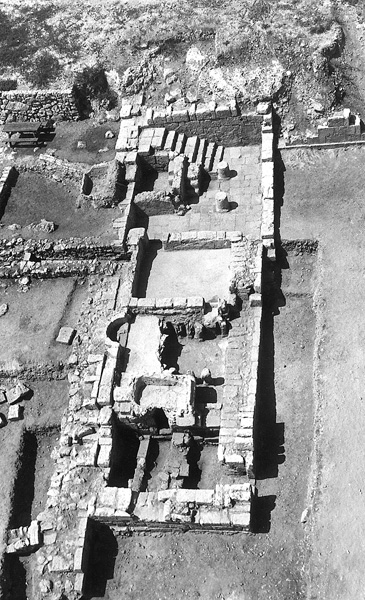

Next to the pool is the bathhouse, a long narrow structure measuring 18.3 by 6.8 m. It is a four-room ashlar-built Reihentyp bathhouse, in which the bather entered and exited via the same route. The first room, paved with stone slabs and measuring 5.3 by 5.3 m, served as a combined dressing room (apodyterium) and cold room (frigidarium). A well-preserved, broad staircase descends to it. Four columns supported its roof. Between the columns and stairs is a small bathing pool. The second room, paved in mosaic, served as the warm room (tepidarium). The third is the hot room (caldarium), which measures 3.7 by 3.6 m, its mosaic floor laid over the roughly 50 stone colonettes (pilae) of the hypocaust. Large clay tiles overlying the pilae were preserved and tubuli (heating pipes) were found along the walls. Uncovered in the rear part of the caldarium was a bathtub within a rectangular niche; on the adjacent wall was a semicircular niche, which held a circular basin (labrum) for washing the face with cold water. The fourth room is the furnace room (praefurnium), with its separate entrance. It is a long narrow room (3.7 by 2.2 m) with a combustion chamber that supplied hot air to the hypocaust and a bronze water heater (not preserved) that would have been placed over it. To the east of the bathhouse was a spacious courtyard enclosed by a retaining wall, a 23-m-long segment of which was found. The courtyard functioned as a kind of palaestra for wrestling and exercising.

Above the entrance to the spring tunnel, a round ashlar-built structure (diameter 9.2 m) that served as a columbarium (dovecote) was identified. The inside of the columbarium is divided by two perpendicular walls. Some 90 m to the west of the columbarium is an olive-oil press. The press consists of three basic elements: a crushing stone, two basins, and a pressing device.

THE BYZANTINE PERIOD (STRATUM II). Next to the Herodian aqueduct was found a c. 350-m stretch of a simpler aqueduct, partly hewn into bedrock and partly built. It provided water to the pool of the large fourth-century CE Shuni theater

THE OTTOMAN AND MODERN PERIODS (STRATUM I). The remains of the village of Umm el-‘Aleq are located at the top of the hill (area B), over the ruins of the Herodian palace. The manor house, also called the Huri House (area D), is to the northwest. Based on coins and pottery, the village was founded no earlier than the nineteenth century. It includes a dozen dwellings spreading over an area of 0.5 a. The house of the mukhtar was built upon the Herodian tower, and the rest of the houses were built in a circle around the shared inner courtyard. The two excavated houses reflect the simple lifestyle of the peasants who lived in the village during the nineteenth century. In 1913, the surrounding lands were purchased by the settlement corporation of Baron Edmond de Rothschild, and following World War I, Jewish colonists from Europe were settled there. Remains of this short period of settlement were found during the excavation. Many of the colonists fell victim to malaria and the settlement was abandoned in 1923.

YIZHAR HIRSCHFELD

INTRODUCTION

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE IRON AGE (STRATUM V). Roughly 140 Iron Age sherds were retrieved, most dating to the Iron Age I, in mixed loci at the top of the hill (area C), in the vicinity of the spring (area A), and on the eastern slope of the hill. A scarab dated to the beginning of the Iron Age was also recovered. It appears that Ramat ha-Nadiv belonged to the Dor district mentioned in the Bible (1 Kg. 4:11).