Tiberias

INTRODUCTION

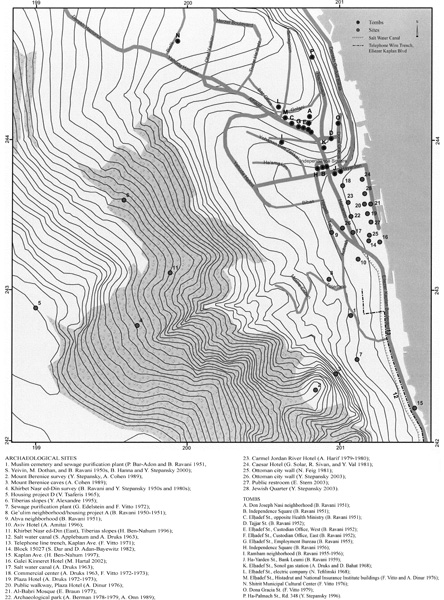

The rapid development of the modern city of Tiberias over the second half of the twentieth century necessitated many salvage excavations throughout the municipal area, most by the Israel Antiquities Authority, formerly the Department of Antiquities. The vast majority of the remains is from the Roman period or later, although some finds antedating the Roman period emerged as well. Discussed in this entry are only the main Israel Antiquities Authority salvage excavations and surveys conducted within Tiberias (not including Hammath Tiberias) until 2004. Excavation sites are referred to by numbers and tombs by letters.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

SITES WITH PRE-ROMAN REMAINS. In 1951, P. Bar-Adon and B. Ravani reported Chalcolithic period and Early Bronze Age I remains at a depth of 3.8–5.5 m below the surface in the area between the Muslim cemetery (Sitt Sakina) and the Imhoff sewage facility, today the sewage purification plant (site 1). Pottery from these periods had previously been found in caves on Mount Berenice. In the 1960s, a large Chalcolithic stone incense altar weighing approximately 40 kg was brought up from the bottom of the Sea of Galilee, about 70 m from the Tiberias shore. These finds are also consistent with the results of the archeological survey conducted on Mount Berenice (site 2) and in its caves (site 3) during the 1980s by Y. Stepansky and O. Cohen, who found evidence that the caves were in use and the upper part of the mountain settled by the Chalcolithic period. Khirbet

One of the caves on Mount Berenice also provided the only Iron Age artifact found so far in Tiberias: an Aramean limestone scarab seal. However, no solid evidence has yet been found for the existence of a permanent Iron Age settlement within the confines of the Roman city; nor have any Iron Age finds been discovered on the hill of the Muslim cemetery next to Sitt Sakina, a site which some have proposed to identify with the biblical city of Rakkath (Josh. 19:35). Identifying Rakkath with Tell

Two excavations of Middle Bronze Age I (Intermediate Bronze Age) burial caves have been conducted in Tiberias’ upper western neighborhoods. These excavations brought to light pottery vessels and copper weapons. Three of the caves were excavated by V. Tzaferis in housing project D (site 5) in 1965 and two others by Y. Alexandre on the Tiberias slopes (site 6) in 1995.

THE MUSLIM CEMETERY AND THE SEWAGE PURIFICATION PLANT. In the 1950s, S. Yeivin, M. Dothan, and B. Ravani reported a number of finds uncovered in the process of laying sewage pipes in the area of the Muslim cemetery (site 1). These included remnants of walls and floors, paving stones, clay pipe sections, a water cistern, stone implements, and sherds from the Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic periods. In 2000, part of a large building complex was unearthed in the course of laying a sewage line near Sitt Sakina. This included a long (35 m) wall made of dressed basalt blocks running north–south and preserved to a height of seven courses (2 m); plastered floors; part of a water reservoir; sherds and coins from the Early Roman, Late Roman, Byzantine (very few), and Early Islamic periods; and a silver amulet with an engraved inscription in square Hebrew script, probably from the Ottoman period.

In 1972, a salvage excavation was conducted by G. Edelstein and F. Vitto inside the sewage purification plant located south of the Muslim cemetery (site 7). Six settlement strata were found, the earliest dated to the end of the Roman period and the latest to the Early Islamic period. Parts of large buildings were found in strata 1 and 2 (eighth century

THE GE’ULIM NEIGHBORHOOD. At the beginning of the 1950s, B. Ravani conducted a number of limited salvage excavations during the construction of what is today known as the Ge’ulim neighborhood or housing project A (site 8). He found remains of buildings, a pool, and various artifacts—clay piping, plaster fragments, a fragment of a basalt door, coins, and sherds—which he dated to the Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic periods. One conspicuous find was a multicolored mosaic band (4.2 by 0.35 m) decorated with geometrical patterns, found in 1951 when a sewer was dug on the eastern edge of the housing project. The mosaic paved the floors of two rooms of a building dated to the Early Islamic period, but Ravani dated the pavement itself to the Roman period.

THE

KHIRBET

OTHER EXCAVATIONS SOUTH OF THE OTTOMAN CITY. In 1963, S. Applebaum and A. Druks conducted excavations in the southern part of the Roman city along the Sea of Galilee’s saltwater canal, which was then under construction along Kaplan Ave. (site 12). These excavations unearthed remnants of baths, plastered walls, pools, and water installations, as well as a fragment of a mosaic floor with a geometrical pattern (at a depth of 3 m, opposite the entrance to the Galei Kinneret Hotel). The Byzantine city wall was documented and exposed to a height of more than 5 m at the spot where it was breached on the southern side of the city, revealing at least four building stages. At the same location, the remnants of a sealed gate were found, underneath which was a clay pipeline leading to the lake. During the excavations along the course of the saltwater canal, an exedra and a basilica were unearthed; among the finds was a fine marble chancel screen, on which a seven-branched menorah with a bird on either side was engraved.

In 1971, F. Vitto conducted a salvage excavation inside the Roman city, along the course of a telephone line trench running parallel to Kaplan Ave. and the saltwater canal, to the east of the Muslim cemetery (site 13). Remains of baths and other water installations—round and square pools, channels, stone basins, and clay pipes—were found and documented, as were walls constructed of ashlars and fieldstones, paved floors (including mosaic fragments), marble slabs decorated with bunches of grapes, architectural elements, and a section of the city’s southern Byzantine wall (2.3 m wide). The sherds and coins found in the excavation date from the Late Roman, Byzantine (the majority), and Early Islamic periods.

In 1982, S. Dar and D. Adan-Bayewitz carried out a limited trial excavation in the open area (block 15027) between the Galei Kinneret Hotel and the Ottoman city wall (site 14). They found some building remains and sherds dating from the Late Roman to the Ottoman periods, part of a pavement of well-dressed basalt slabs, and a storage pit dating to the ninth–tenth centuries CE.

In 1997, a salvage excavation was conducted by H. Ben-Nahum along Kaplan Ave., opposite the municipal beach (site 15). Construction remains from a number of periods were found in the excavation of four squares. These included parts of rooms (perhaps storehouses), stone and plaster floors, and fragments of mosaic pavements. According to the pottery found at the site, the last stage of habitation is to be dated to the Early Islamic period. The architectural remains are similar to remains located just to the east of the excavated area and at present integrated into the avenue’s eastern sidewalk. All these structures may be related to an ancient wall—apparently Roman or Byzantine—running in a north–south direction along and parallel to the lakeshore, remnants of which were noted and mapped by G. Schumacher as early as 1887. Some portions of this wall were still visible above ground in the 1970s, before the area was converted into a municipal beach.

THE GALEI KINNERET HOTEL. The salvage excavation at the Galei Kinneret Hotel (site 16) was conducted by M. Hartal in 2002. Remnants of five settlement strata were found. The earliest stratum belongs to the Early Roman period. In the northern part of the excavation, part of an impressive public building was unearthed, including a bow-shaped wall built of dressed stones and filled with rocks and lumps of hard plaster. The wall is c. 9 m thick and has been preserved to a height of nearly 2 m. On top of the wall a small bronze figurine of a winged youth, probably a Cupid, was found. The structure’s shape and construction method indicate that it was an important public building in Roman Tiberias, probably the local stadium, mentioned a number of times by Josephus. He relates that, after the sea battle between the Jews and the Romans near Migdal, thousands of Jewish prisoners-of-war were gathered in the stadium of Tiberias, where the Romans selected those to be executed and those to be sold into slavery. The section of wall that was excavated would appear to be part of the base at the stadium’s southeastern corner, above which there would originally have been seats for the audience. Geological tests and the findings to the south of the stadium wall indicate that this area was located on the shore of the Sea of Galilee during the first and second centuries CE, outside the city limits. Stone “measuring cups” found in this area constitute evidence for the existence of a Jewish community in Tiberias at this time. The structure was destroyed and abandoned at the end of the third or the beginning of the fourth century CE.

The excavated area was part of the city in the Byzantine period. Remnants of walls, arches, and floors of an elongated hall (9 by 4.8 m) were revealed above the ruins of the stadium. In the southern part of the excavation area were uncovered the remains of a large building, including a 14 m stretch of its outer wall and the entrance to the structure, exposed to a height of 2.10 m. Three columns were erected in front of the building, made of column drums in secondary use; among the spolia was a Nabatean capital used at the base of one of the columns.

In the Early Islamic period, two large buildings occupied the excavation area. A c. 35 m stretch of the eastern wall of the northern building was excavated, as were a number of lateral walls over a distance of up to 8 m. Of the southern building, the foundations of two walls and the threshold are all that remain. East of the buildings an unplastered pool (5 by 3.5 m and 1.95 m deep) was found, constructed of dressed stones with a lower course consisting of two rows of column drums. The pool was probably built in shallow water near the lakeshore and was used for storing fish awaiting sale. The gaps between the drums ensured circulation of freshwater from the lake but were narrow enough to prevent the fish from escaping.

There was evidence in the excavation area of seismic activity, which caused the western part of the site to sink c. 70 cm. As a result, walls cracked and moved, the southern building collapsed, and the northern building sank. Pottery and bronze vessels that had apparently fallen during the earthquake were recovered from the floor of the northern building. These finds make it possible to identify the event as the great earthquake of January 13, 749 CE, which caused considerable damage throughout the region, including at Beth-Shean and Hippos (Sussita).

The site was partially resettled after the earthquake. On the northern side, pits with dressed stone walls were found on the northern side of the site; they contained finds dated to the Fatimid period. To the same period belong a number of other installations, including pools and work surfaces. A large structure was erected on top of the abovementioned southern building. Its foundations were sunk into silt deposited by inundations of the lake. A 14 m stretch of the building was exposed.

A double pool (2.5 by 2 m and 0.3 m deep) covered with plaster and overlying sherds of vessels used in sugar production was found at the site and dated to the twelfth century CE, when the area was outside the city limits. It remained so until the period of the British Mandate, when the hotel was built.

EXCAVATIONS INSIDE THE OTTOMAN OLD CITY. Since the 1960s, some 20 salvage excavations have been conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority (formerly the Department of Antiquities) within the Ottoman walls of Tiberias. In 1963, A. Druks conducted probes during the construction of the saltwater canal, which crossed Tiberias from north to south. Inside the city he reported finding disturbed strata to a depth of 4 m. In one place an accumulation of Crusader period sherds was encountered. Where the saltwater canal broke through the Ottoman city wall on the city’s southern side, a 40 m-long wall was found 5 m below the surface, built in a north–south direction, perpendicular to the Ottoman wall and passing underneath it (site 17). This wall, built of headers and stretchers, is 2.3 m wide and has been preserved to a height of four courses. The excavators were unable to date the wall, but noticed that the foundations of the Ottoman wall were laid directly on top of it.

As part of the preparations for developing the area around the al-‘Umari Mosque (today the commercial center south of the mosque; site 18), preliminary excavations were conducted by A. Druks in 1965. Remains of walls, as well as coins and sherds from the Early Islamic period, were found; Crusader silver coins were unearthed on the floor of a partially excavated building. A relief depicting a menorah, a shofar, and a lulav was discovered not in situ. In 1972 and 1973, F. Vitto conducted some further test excavations in this area and uncovered walls dating from the Crusader period and a stone pavement at a depth of 3 m, perhaps a street, dated to the Early Islamic period.

Comprehensive excavations were conducted in the 1970s as part of the preparations for the construction of a hotel and the development of the area near the shore to the southwest and west of the

In 1976, E. Dinur performed a salvage excavation near the Plaza Hotel, where a public walkway to the promenade was being built north of the hotel (site 20). This excavation was the first in which remains of the twelfth-century Crusader fortress of Tiberias were found. The most impressive find was a massive north–south wall (3.8 m wide), exposed over a length of 15 m and consisting of two faces of dressed stones and a fill of fieldstones and mortar; columns in secondary use were also employed in its construction. The wall’s external, western face is inclined outward at the base. In Dinur’s opinion, it was part of the fortress’ external west wall, near its southwestern corner. Another wall approached this one from the east; incised on one of its stones was a game board with three concentric squares, of the kind known from other Crusader sites (such as ‘Atlit and Belvoir).

Additional remnants of the Crusader fortress were found by E. Braun in 1977, slightly to the east of Dinur’s excavation, near the western side of the

In 1978 and 1979, A. Berman conducted salvage and pilot excavations over a relatively large area (90 by 50 m) west of the Plaza Hotel; today the site is an archeological park (site 22). The finds here included the remains of a residential area dated to the Early Islamic period; a synagogue with a mosaic floor containing a dedicatory inscription in Greek, dated by the excavator to the same period, although it was in fact probably constructed during the Byzantine period; and a large, fortified structure apparently erected during or just before the Crusader period.

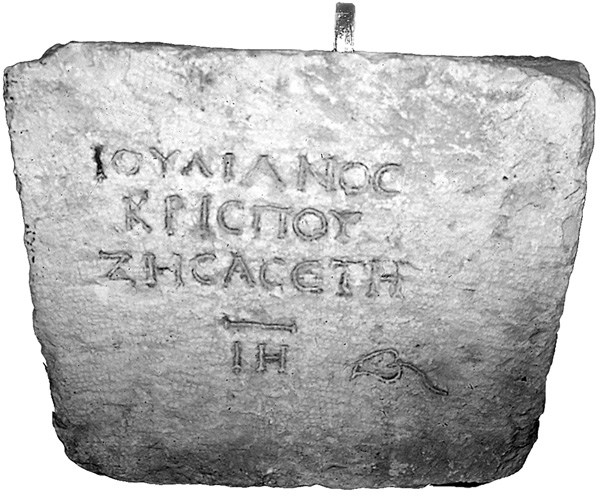

In 1979 and 1980, A. Harif, Y. Val, and N. Feig conducted excavations at a proposed construction site for a large hotel, today the Carmel Jordan River Hotel, in the center of the old city (site 23). The excavations unearthed the remains of a large Crusader church and a thick wall dated to the Byzantine and/or Early Islamic period. The wall was probably part of the sixth-century CE Byzantine city wall of Tiberias, which descended northward from the top of Mount Berenice. It was apparently at this site that a limestone coffin was found with an engraved Greek inscription: “Julianos son of Crispos lived 18 years.”

In 1981, G. Solar, R. Sivan, and Y. Val conducted a salvage excavation on the plot where the Caesar Hotel was to be built (site 24). The remains of a large structure along an east–west axis were found. The building, whose threshold was a lintel in secondary use bearing a carved cross, remained in use until the nineteenth or twentieth century CE. The excavation also revealed a north–south wall constructed entirely of basalt column drums (near and to the east of the Señor Synagogue; a similar wall was found by M. Hartal in the Galei Kinneret Hotel excavation of 2002; see above), as well as thick accumulations of silt, probably deposited during the devastating flood of 1934.

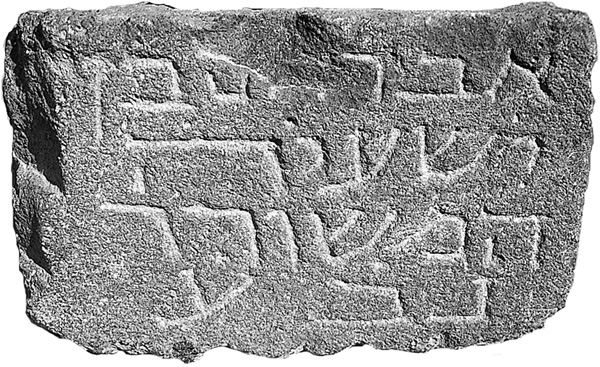

Also in 1981, N. Feig carried out a pilot excavation in three small areas next to the southern Ottoman wall, in preparation for the wall’s reconstruction (site 25). Remains of buildings dated to the Byzantine, Early Islamic, and Mameluke periods were found. In one of the excavated areas, Crusader period sherds were recovered near the wall’s foundation, leading the excavator to conclude that this section of the wall was constructed later than the Crusader period. During the preparatory work for the construction of a large parking lot next to the inside of the wall in 1981, Y. Stepansky discovered a gravestone with a Hebrew inscription, “Abraham the son of Isaiah the meshorer, may he rest in peace”; it probably dates to between the tenth and the mid-fifteenth centuries CE.

In 1989, A. Onn performed a supplementary excavation in the area excavated by A. Berman in 1978–1979, west of the Plaza Hotel, before it became an archaeological park (site 22; see above). The synagogue was reexamined and additional remains of buildings from the Late Roman, Byzantine, Early Islamic, Crusader, and Ottoman periods were found. In a stratum dated to the Fatimid period (tenth–eleventh centuries

Additional trial excavations along the southern Ottoman wall were carried out by Y. Stepansky in 2003, in preparation for the preservation and reconstruction of the section that lies to the west of ha-Banim St. (site 26). In three squares along on the inside of the northern face of the Ottoman city wall, the excavators found the remains of a 2.2 m-wide wall adjacent and running parallel to the east–west Ottoman wall. The wall had two faces of dressed stones, mostly laid as headers. The wall was exposed to a height of five courses in one 3 m section. Judging from the sherds found among the stones of the wall, it is to be dated to the eleventh century CE (the end of the Fatimid period) or slightly later. It may have been the southern city wall after the city area was reduced at the end of the Early Islamic period or following the city’s capture by Tancred at the beginning of the Crusader period.

In 2002, E. Stern excavated a single square trench prior to the construction of a public restroom near a walkway leading to the lake promenade, west of the Russian hostel (site 27). The remains of five settlement strata were found, the most important of which are strata 4, 3, and 2, dating to the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries CE, respectively. These strata contained the remains of a building first constructed during the Crusader period and remaining in use until the fourteenth century. Floors, glass vessels, and a number of in-situ pottery vessels, all dated to the thirteenth century CE, were also found. The construction method—two faces of dressed stones with a fill of small fieldstones and mortar—is similar to that employed in the Crusader fortress of Tiberias to the north.

In 2003, Y. Stepansky carried out a salvage excavation in the old Jewish Quarter near the western façade of the

TOMBS. Burial remains have been found in many of the excavations conducted in Roman Tiberias and within the Ottoman city walls. They are usually in the form of stone coffins, gravestones, or other tomb-related artifacts, such as ornamented basalt-stone doors. Some have been found in situ underneath the earliest settlement strata, others out of context or in secondary use in later construction.

At the northern edge of the Ottoman city—in the vicinity of the Scottish Compound, the Seraya, and the Ottoman Citadel—and further north and west, along

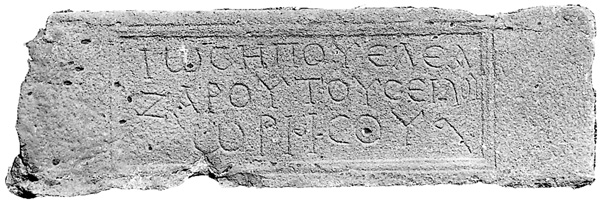

Two monumental tombs were excavated outside the main burial field. One (tomb N) is a 10-by-8 m mausoleum excavated by F. Vitto in 1976 on the construction site of the Shitrit Municipal Cultural Center; it is dated to the end of the first and beginning of the second centuries CE. The other (tomb O) contains two adjacent mausolea constructed of dressed basalt stones and architectural elements, excavated by Y. Stepansky in 1996 on Road 348 (the planned extension of ha-Palmach St.), and dated to the late second–early third centuries CE. The northern mausoleum, whose flagstone floor was preserved in its entirety, contained an underground repository for secondary burial under the center of the floor and sealed by a round stone plug. The southern mausoleum, with preserved foundations and finely constructed burial chambers, had a stone door and lintel with a Greek inscription reading “Yosef, son of Eleazar, son of Shila, of

YOSEF STEPANSKY

THE “HOUSE OF THE BRONZES” AND ASSOCIATED REMAINS. In 1998, a salvage excavation was conducted at the sewage purification plant at the foot of Mount Berenice, c. 300 m west of the shore of the Sea of Galilee, by Y. Hirschfeld and O. Gutfeld, on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Remains of buildings of the Fatimid period (970–1099 CE) were uncovered, among which was a hoard of bronze vessels hidden in three large storage jars. The hoard consisted of almost 1,000 vessels, many intact, as well as thousands of metal scraps of industrial waste and some 80 coins. The coins included a group of about 70 Byzantine coins of the type known as “anonymous folles,” their obverse bearing the image of Jesus as emperor, their reverse an inscription, such as “Jesus Christ the victorious.” The date of the issues in this cache suggests it was probably concealed before the Seljuk massacre at Tiberias in 1075.

The excavation, conducted in a very limited area (c. 600 sq m), came upon three strata. In the lowest stratum, about 4 m below surface level, walls of the Byzantine and Umayyad periods (stratum III) were exposed. The remains of the walls were covered by a thick layer of alluvial soil and fallen stones deposited probably as a result of the earthquake that struck Tiberias around the mid-eighth century CE. Above the alluvial soil were Abbasid period walls (stratum II), built of local basalt, mostly reused dressed stones. On top of the walls were the Fatimid period buildings (stratum I).

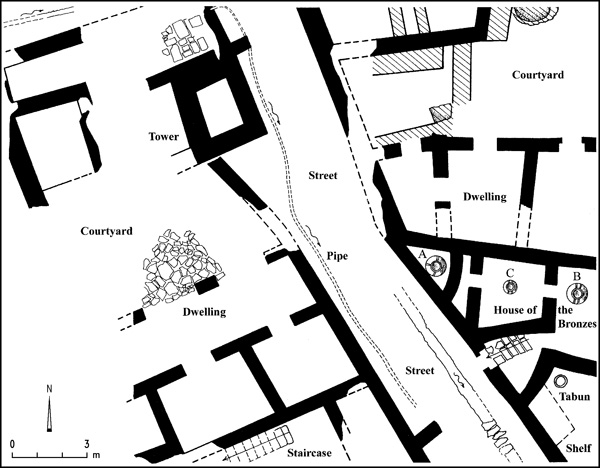

The remains of the Fatimid period included parts of a street with houses on both sides, c. 20 m of which was exposed. The street, 3–5 m wide, was paved diagonally from southeast to northwest, conforming to the topography of Mount Berenice. Beneath the street was found a clay water supply pipe and a drainage pipe.

The walls of the houses flanking the street were preserved to a height of 1.5–2 m. West of the street was uncovered part of a three- or four-room house fronted by a stone-paved courtyard. A flight of stairs in the rear of the house indicates that it had a second story. North of it, at a higher level, was a square tower (3.6 by 3.2 m) that may have served as a water tower. North of the tower was a stone pavement; a clay pipe beneath it was part of the municipal water system. Tiberias in the Islamic period appears to have been a well-run city with a high standard of living.

East of the street, parts of two adjoining houses were excavated, the northernmost consisting of three or four rooms around a courtyard paved with plastered pebbles. In the southern house—the “House of the Bronzes”—three rooms and part of a courtyard were uncovered. That courtyard had an irregular shape, adapted to the dense urban construction. From the courtyard a flight of stairs led to the higher part of the street. South of the flight of stairs was a room with a tabun and a shelf; to its north were two other rooms—a front room and a back room.

The front room was the larger of the two (7 sq m) and had an opening 0.6 m wide leading to the courtyard. Built into the wall of the northern room were two jars, one containing bronze scrap and the other empty. Beneath the floor, at a depth of 0.6 m, was found one of the three jars containing the hoard (storage jar C). The back room, triangular in shape, was smaller (4 sq m), and it was connected to the front room by a particularly small doorway (0.5 m wide and 0.9 m high). Another jar (storage jar A) was found resting on the floor in a corner of the back of the room. Because of the jar’s great size (0.85 m in diameter and 1.1 m high), it may be assumed to have been placed in the room during its construction. To keep the jar upright, a 1 m-high wall was built across the width of the room. The third jar (storage jar B) was discovered at a depth of 0.8 m beneath the courtyard. Small bronze fragments and a thin layer of greenish metal shavings were found on the floors of the rooms and courtyard, evidence that the building served as an industrial facility for producing bronze artifacts.

The majority of the objects recovered in the excavation can be dated to the ninth–eleventh centuries CE, while some are earlier, dating to the sixth–eighth centuries CE. The hoard constitutes the largest assemblage of bronzes from this period ever found. Also retrieved were a glass bottle and several metal objects, including tools belonging to a workshop, such as iron scissors; molds for casting; and raw material for preparing metal, such as a lead ingot. The majority of the artifacts were produced by hammering and casting techniques, some cast in one piece and others in parts, then welded together. A tripod bore an Arabic inscription reading “made by Abbas.”

The bronzes of the hoard can be divided into three main categories: lighting implements, tableware, and kitchen implements. The lighting implements include candlesticks, candelabra, oil lamps, and funnels for filling lamps. The tableware consists of bowls, goblets, cups, jugs, and bottles. The kitchen implements include buckets, ladles, cooking pots, frying pans, and mortars. Also recovered were a pair of gilded stirrups, hooks, nails, and dozens of furniture parts, such as legs, handles, hinges, locks, and strips and plaques for decorating elegant wooden boxes. Some of the objects were decorated with Kufic inscriptions of blessings and wishes for health, wealth, and happiness.

YIZHAR HIRSCHFELD, OREN GUTFELD

The Coins

Mount Berenice

The “House of the Bronzes” and Associated Remains

INTRODUCTION

The rapid development of the modern city of Tiberias over the second half of the twentieth century necessitated many salvage excavations throughout the municipal area, most by the Israel Antiquities Authority, formerly the Department of Antiquities. The vast majority of the remains is from the Roman period or later, although some finds antedating the Roman period emerged as well. Discussed in this entry are only the main Israel Antiquities Authority salvage excavations and surveys conducted within Tiberias (not including Hammath Tiberias) until 2004. Excavation sites are referred to by numbers and tombs by letters.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

SITES WITH PRE-ROMAN REMAINS. In 1951, P. Bar-Adon and B. Ravani reported Chalcolithic period and Early Bronze Age I remains at a depth of 3.8–5.5 m below the surface in the area between the Muslim cemetery (Sitt Sakina) and the Imhoff sewage facility, today the sewage purification plant (site 1). Pottery from these periods had previously been found in caves on Mount Berenice. In the 1960s, a large Chalcolithic stone incense altar weighing approximately 40 kg was brought up from the bottom of the Sea of Galilee, about 70 m from the Tiberias shore. These finds are also consistent with the results of the archeological survey conducted on Mount Berenice (site 2) and in its caves (site 3) during the 1980s by Y. Stepansky and O. Cohen, who found evidence that the caves were in use and the upper part of the mountain settled by the Chalcolithic period. Khirbet