Another View: Small City, Few People

Professor David Ussishkin claims that the city wall of Jerusalem built by the exiles returning from Babylon, as described in the book of Nehemiah, enclosed an enormous area co-extensive with the city wall that enclosed Jerusalem when the Babylonians conquered and burned it in 586 B.C.E. (“Big City, Few People: Jerusalem in the Persian Period,” BAR 31:04). Ussishkin is plainly wrong.

Ussishkin recognizes that the returning exiles “were neither wealthy nor particularly skilled.” In addition, he concedes that there were “few returning exiles.” He also accepts Nehemiah’s statement that the rebuilding of the wall was completed in 52 days. Indeed, everyone agrees that the detailed description in Nehemiah 3 regarding the course of the wall and its towers and gates is authentic and based on a primary source, reflecting an intimate knowledge of the topography of the city.

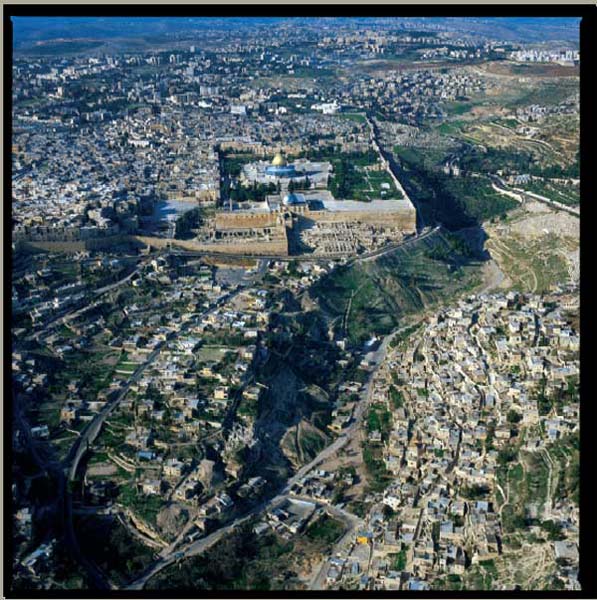

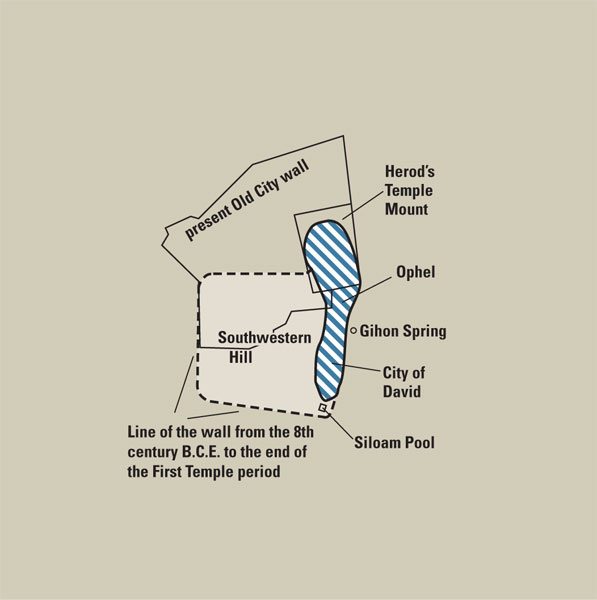

All this points to the conclusion that most scholars who have studied the problem have reached—namely, that the city wall that the returning exiles rebuilt enclosed only the 10 or 12 acres known as the City of David (the original Israelite settlement) plus the area around the Temple Mount to the north.

Ussishkin claims that the city wall built by the returning exiles at that time also included the Southwestern Hill, although most of the city enclosed within his suggested wall—covering about 150 acres—was uninhabited. To quote him:

Not all of the area within the Persian period walls was inhabited by the few returning exiles. Large areas of the city remained unpopulated [i.e., mainly the Southwestern Hill]. Most of the returning exiles lived in the City of David and the area near the Temple Mount.

It has now been conclusively demonstrated that at the end of the eighth century B.C.E. (the time of King Hezekiah of Judah), Jerusalem very considerably expanded to include the hill west of the Temple Mount (today the area of the Jewish and Armenian quarters in the southern part of the Old City and Mount Zion to its south). This hill is separated from the eastern ridge (known as the City of David and Temple Mount) by a valley called the Tyropoeon Valley, which in ancient times was much deeper than it is today.

Ussishkin argues that there was no wall on the west side of the City of David for the returning exiles to rebuild. Therefore, the returning exiles had to proceed to rebuild the wall that extended across the valley and over the Southwestern Hill following the eighth-century B.C.E. expansion of the city.

Ussishkin recognizes that a wall once existed on the western side of the City of David in the Middle Bronze Age, about a millennium before the eighth-century B.C.E. wall around the expanded city. Although no remains of this Middle Bronze Age wall have been uncovered on the western side of the City of David, it has been found in abundance on the eastern side. This is because very little excavation has been conducted on the western side, so, as Ussishkin recognizes, this might be expected. In his own words:

We assume, however, that certainly the [Middle Bronze Age] city was fortified on all sides and that therefore the wall must have followed the topographical line on the western side [of the City of David].

In the eighth century B.C.E., there was no need to build a wall on this western edge of the City of David because the city had greatly expanded to the west to include the Southwestern Hill (Mount Zion), says Ussishkin. Since there was no eighth-century B.C.E. wall on the western edge of the City of David, Nehemiah was forced to continue westward to wall the Southwestern Hill also.

But what about the Middle Bronze Age wall that Ussishkin admits existed on the western edge of the City of David. Ussishkin’s answer:

The theoretical possibility that Nehemiah restored the Middle Bronze wall that had extended along the western side of the City of David and had gone into disuse one thousand years earlier does not make sense.

On the contrary, it makes a great deal of sense.

Unlike the eastern slope of the City of David, which has seen many large-scale excavations, the western edge has basically undergone only one significant excavation. If excavations were to take place along this slope above the Tyropoeon Valley, they certainly would reveal the remains of an early wall on bedrock on the western side of the City of David. It would probably be a wall of massive proportions, built during the Middle Bronze Age, and certainly used in one form or another, with repairs and additions, through the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. At the end of the First Temple period, this wall would have become an internal fortification of diminished importance in light of the wall enclosing the Southwestern Hill. It is this wall (or its later reconstruction) that Nehemiah repaired.

Ussishkin’s next argument is that Nehemiah describes a large number of towers and gates in the wall, suitable only for a wall of great length—which is to say, one that enclosed the Southwestern Hill. The large number of gates and towers, however, must be understood in light of Jerusalem’s topography, its unique history and the fact that it was the capital of the kingdom of Israel and Judah. The City of David sits atop a narrow rocky promontory defended on the east by the Kidron Valley and on the west by the Tyropoeon Valley. In the north, the highest part of the promontory rises to the Temple Mount. The city was composed of several sub-areas, each with a definable function in the daily life of the city: on the south was the residential area; on the north was the Temple and related buildings; between these two areas was the Ophel, the site of the royal palace and administrative buildings. The city wall, built on this long, narrow promontory, needed several gates to allow easy daily access to the roads leading in and out of it, to agricultural areas surrounding it, and to its water source near the Kidron Valley floor on the east.

The wall the exiles rebuilt is referred to in three places in the Book of Nehemiah: Nehemiah’s inspection of the city’s ruined walls by night (Nehemiah 2:13–16), the rebuilding of the walls (Nehemiah 3:1–32) and the celebratory procession along the walls once the rebuilding was completed (Nehemiah 12:37–39). Only three main gates to the City of David seem to be referred to: the Valley Gate on the west, the Dung Gate on the south (beside which was the Fountain Gate associated with the Siloam Pool), and the Water Gate on the northeast, close to the Ophel. The remainder of the gates mentioned in the description of the wall’s construction—the Sheep Gate, the Fish Gate, the Ephraim Gate and the Old Gate—were located in the part of the wall that enclosed the Temple area. The Sheep Gate was certainly of religious significance related to the Temple rite. That’s why its construction was attributed to the priests (Nehemiah 3:1). The Old Gate (Sha’ar Hayeshanah) allowed for direct access to the “secondary” (hamishneh) quarter that had been located on the Southwestern Hill.1 The other gates noted in Nehemiah—the Horse Gate, the East Gate, the Muster Gate (Sha’ar Hamiphaqed), and the Gate of the Prison Compound (Sha’ar Hamatara)—were all within the Temple complex itself, rather than part of the city wall. Thus, it is not very surprising that the wall of Jerusalem, which surrounded the City of David and the Temple Mount and measured roughly 7,000 feet long, included a relatively large number of gates: three in the City of David and four on the Temple Mount. The rest of the gates mentioned by Nehemiah were internal, within the Temple Mount complex.

Ussishkin accepts Nehemiah’s statement that the rebuilding of the wall was accomplished in just 52 days. Is it possible that the impoverished returning exiles could rebuild a wall 7,000 feet long in just 52 days, especially in the face of all the other hurdles and difficulties that stood in their way? This is simply untenable in my opinion, leaving us with the only possible conclusion that Nehemiah’s wall encompassed only the City of David and the Temple Mount.

Ussishkin admits that the Southwestern Hill was unpopulated when the exiles returned, a fact clearly confirmed in the many excavations on the Southwestern Hill, none of which has found any remains whatsoever from the Persian period. What, then, would be the urban rationale for enclosing this large area within a fortification wall.

Even more significant, if the First Temple period wall was indeed rebuilt by Nehemiah on the Southwestern Hill (as Ussishkin contends), why haven’t any remnants of this construction been found? Many excavations have been undertaken all along this fortification line (known as the “First Wall” in Josephus’s description), revealing long segments of the First Temple wall. Every segment of the wall discloses the same historical-architectural story: atop the remains of the wall from the end of the First Temple period are remains of the Second Temple period fortification, dating to the Hasmonean (late second–mid-first century B.C.E.) and Herodian periods (mid-first century B.C.E.—first century C.E.)2—long after the time of the returning exiles (the Persian period). Not a single bit of a Persian period fortification has been found along the line of the First Wall around the Southwestern Hill. Could it be that Nehemiah’s wall has effectively vanished, leaving absolutely no trace of its existence? Such a notion is simply indefensible. Moreover, if the First Wall had been rebuilt by Nehemiah, why did the Hasmoneans need to construct it anew from its foundations? (The remains of the First wall are founded mostly on bedrock).

The last 35 years have brought to light much new data advancing our knowledge of Jerusalem throughout its history, including the Persian period. One of the clearest conclusions of this new archaeological research is that the Southwestern Hill was neither settled nor fortified in the days of Nehemiah. The city of the returning exiles was concentrated in the area of the City of David and the Temple Mount only.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

R. Grafman, “Nehemiah’s ‘Broad Wall,’” Israel Exploration Journal 24 (1974): 50–52; Nahman Avigad, Discovering Jerusalem (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1983), pp. 56–60. On the idea that the name Sha’ar Hayeshanah (“Old Gate”) is a distortion of the original name Sha’ar HaMishneh (“Secondary Gate”), see B. Mazar, “Jerusalem from Isaiah to Jeremiah,” in B. Mazar, ed., Biblical Israel, State and People (Jerusalem, 1992), p. 103.

A summary of the remains of the First Wall around the Southwestern Hill can be found in H. Geva, “The ‘First Wall’ of Jerusalem during the Second Temple Period, an Architectural-Chronological Note,” Eretz-Israel 18: pp. 21–39 (Hebrew)—and also in E. Stern, ed., The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, (Jerusalem, 1993), pp. 724–729. A detailed description of a section of the First Wall along its northern side can be found in H. Geva (ed.), Jewish Quarter Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem, Conducted by Nahman Avigad, 1969–1982, Vol. I: Architecture and Stratigraphy: Areas A, W, and X-2, Final Report. Jerusalem, 2000, pp. 131–197; H. Geva, Summary and Conclusions of Findings from Areas A, W and X-2, In H. Geva, Jewish Quarter Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem, Conducted by Nahman Avigad, 1969–1982, Vol. II, The Finds from Areas A, W, and X-2, Final Report. Jerusalem, 2003, pp. 501–552.