Archaeological Views: Archaeology, Israelite Cosmology and the Bible

028

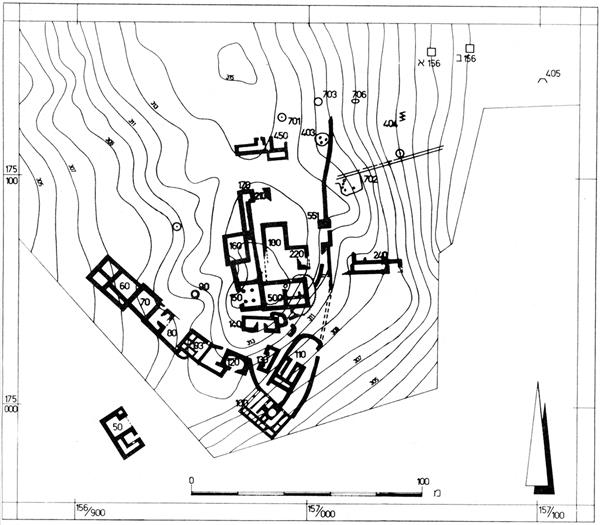

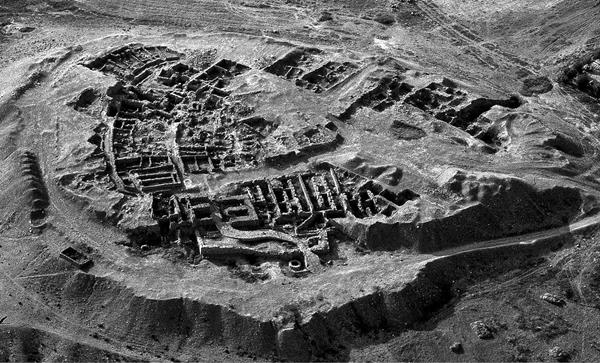

A thorough examination of Iron Age II (c. 1000–86 B.C.E.) dwellings excavated in Israel and Judah reveals a strong tendency to orient houses to the east.1 This preference is even far more noticeable in isolated, self-standing buildings, which had relatively little restrictions on their construction. More than 80 percent of these self-standing structures were oriented east, southeast and northeast.

This preference to orient houses to the east was evident also in nucleated settlements, that is, villages and cities clustered around a center, where any new construction would need to conform to the existing settlement fabric. Even there, some 60 percent of all houses were found to be oriented in this direction. The north and the south were also represented, but the west (including northwest and southwest) were almost completely avoided. These archaeologically detected tendencies cannot be accidental.

Climatic and functional considerations cannot account for this phenomenon. Lighting considerations, for example, would make the north (not the west) the most underrepresented direction, and heat concerns would also influence the north-south axis, rather than the east-west axis. As for winds, it is true that most winds in the Land of Israel are west or northwest winds. In the Middle East, a west wind (breeze) is typically something pleasant that people look forward to, in contrast to the hot, east wind (sharqiyya or khamsin), which is to be avoided. The influence of winds should, therefore, favor the west orientation of houses.

The tendency to direct doorways of structures to the east and to avoid the west impacted not only dwellings but also city gates. It appears that through complex mechanisms this tendency even had an impact on Iron Age urban planning.2

If not practical considerations, what else could account for the easterly orientation of structures and settlements in Iron Age Israel? Many ethnographic studies have demonstrated the strong influence of cosmological principles—that is, the way societies understand the universe, its origin, structure, laws and fate—on the planning of buildings and settlements. Interestingly, in many cases across the globe, it is the east that is indeed the preferred direction. The reasons for this strong tendency to favor the east are obvious: it is the direction of sunrise, which commonly symbolizes beginning or renewal. This preference is contrasted with the west, the direction of sunset, often symbolizing the end or death.

In the complex cosmology of the Toraja people of Indonesia, for example, the east is the direction of life, the rising sun, deities and life-affirming rituals.

The Nuer people of southern Sudan correlate the transition from birth to death with the progress of the sun. They identify the west with death and the east with life. The Nuer use the same verb for burying (a person) and setting (of the sun). For the ancient Egyptians, too, the west was the realm of death.

These are but a few examples. Could such a cosmology influence the orientation of Iron Age houses in ancient Israel? The above examples suggest it is possible, but not more than that.

Ancient Israelites, however, provide us with an additional source of information—their language, which can reveal much about their cognition. The common Biblical Hebrew word for the east is qedma (“forward”; קרימה), while the west is akhora (“backward”; אחןרה). The Israelites, like other ancient societies, viewed the world while facing the east. Additional words for those cardinal directions indicate that the east had a good connotation while the west had a bad one. The common word for west in Biblical Hebrew is yam, literally “sea” (ים), which is the most conspicuous geographic element in this direction. But the word yam, besides designating a large body of water and westerly orientation, had some other meanings as well. In many cases those meanings represent the forces of chaos, sometimes personified in the Leviathan and other legendary creatures equaling the “Anti-God” in Biblical thinking, where God is responsible for “order” (see Isaiah 27:1; Psalm 74:13-14; Job 26:12).

The negative meaning of the word commonly designating the west strengthens the view that the westerly direction was not only at the “back” of the Israelite ego, but was also regarded as inauspicious.

Various Biblical passages betray a worldview according to which God resided in the east. In the Exodus story, for example, the Sea of Reeds is forced to open up for the Israelites by the east wind (ruakh qadim), which is the wind of God. This is not because God needed a “hot” wind to dry up the sea, but because, in Israelite cosmology, God resided in the east, and hence God’s wind is by definition an east wind. No less interesting is the fact that the “bad guy” in the story is the sea (echoing other ancient Near Eastern stories).

The notion that God dwells in the east 029is even more explicit in various passages in Ezekiel 40–48, where the prophet describes the vision of the new Jerusalem temple. According to Ezekiel’s description, the envisioned temple courts had three gates each: the main one in the east and two more on the south and north. No entrance is described in the west.

Perhaps even more significant is the description of the eastern gate, which is the main gate through which Ezekiel enters the temple (40:4ff): “I saw the glory of the God of Israel coming from the east … The glory of the Lord entered the temple through the gate facing east” (Ezekiel 43:1, 4).

In Ezekiel 46, the inner eastern gate is described as being closed except on the Sabbath and the beginning of the new month, when the nasi (prince) enters the court through this eastern gate.

Topographically, the easiest way to approach the actual Temple was from the north (or south). But as the northern edge of the Temple Mount was also the northern edge of the city, this was probably out of the question, and the best way to approach the Temple from within the city was from the south. To the east of the Temple Mount lies the Kidron Valley, which lay outside the city-wall and from which it was very difficult to climb up to the Temple. The orientation of the main entrance in Ezekiel’s vision is therefore not related to the actual geography or topography, and it could have been chosen only for cosmological reasons.

We can conclude that the preference for the east and the complete avoidance of the west are characteristic of both the Biblical description of the envisioned temple and the archaeological reality. In the Bible, the east is the main direction, the south and north are present, but the west is not even mentioned. Archaeological evidence demonstrates the same pattern: the east is preferred, north and south are present, and the west is avoided whenever possible.

Both kinds of evidence are in perfect accord—the Biblical description of the envisioned temple together with other texts and even the language on the one side, and the archaeological data on the other.

068

It appears that Israelite cosmology is responsible for the tendency to orient Israelite Iron Age dwellings to the east.

A thorough examination of Iron Age II (c. 1000–86 B.C.E.) dwellings excavated in Israel and Judah reveals a strong tendency to orient houses to the east.1 This preference is even far more noticeable in isolated, self-standing buildings, which had relatively little restrictions on their construction. More than 80 percent of these self-standing structures were oriented east, southeast and northeast. This preference to orient houses to the east was evident also in nucleated settlements, that is, villages and cities clustered around a center, where any new construction would need to conform to the existing settlement fabric. Even there, some 60 […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.