Biblical Views: Text Archaeology: The Finding of Lightfoot’s Lost Manuscripts

028

When we think of archaeology, we think of digging in the ground—of trowels, spades, measuring lines and the like. We think of hot sweaty work in the sun during the summer digging season. While this image is certainly a prevalent and correct one up to a point, at its core archaeology is about studying ancient cultures by what they have left behind. This brings me to the subject of text archaeology—the study of unknown, lost or missing texts.

Texts, like the famous Codex Sinaiticus, are often discovered in existing buildings. The Codex Sinaiticus was discovered in St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai desert. No digging was required, just sorting through a pile of papyri.

This brings me to J.B. Lightfoot, without much dispute the most famous New Testament scholar in the English-speaking world in the 19th century. Lightfoot was especially well known for his commentaries on St. Paul’s Epistles and on the Apostolic Fathers.

Almost 40 years ago, as an eager young doctoral student looking for interesting manuscripts, I was at Durham Cathedral in England. One day in 1978 in the Monk’s Dormitory of the cathedral, I was looking at display cases with manuscripts in them. In one them was a manuscript from about 1855 containing Lightfoot’s detailed exegetical notes on Acts 15, perhaps the most disputed of all passages in the Acts of the Apostles. The manuscript was in an ancient notebook, so I concluded that there had to be many more such manuscripts. I reported this to my doctoral supervisor, Professor C.K. Barrett, and we talked of doing a proper search, but nothing came of it.

When I returned to Durham in the 1980s to conduct more research, I told Professor James D.G. Dunn, the Lightfoot Professor of New Testament, about the possibility that there may be more of Lightfoot’s manuscripts. Still, it was not investigated until sometime in the late 1980s when scholars Geoffrey Treloar and Bruce Kaye apparently looked through some of the manuscripts and used some of the neglected material to produce a monograph about Lightfoot as a historian. Nothing was said or done about the hundreds and hundreds of pages of commentary materials in storage in the Monk’s Dormitory.

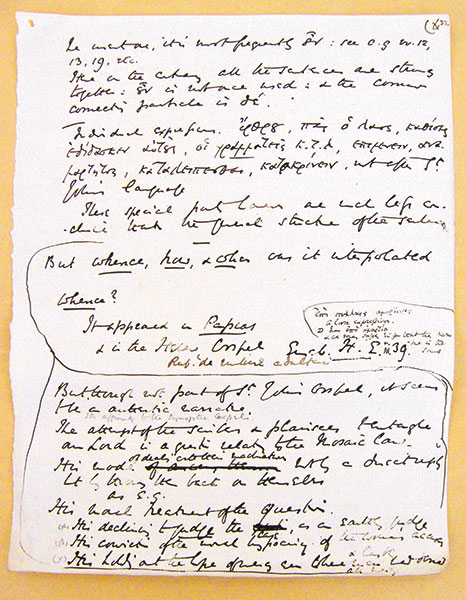

In the spring of 2013, I was on sabbatical at St. John’s College at Durham University. While it was not my sabbatical project, I was determined to get to the bottom of what exactly still remained in the Lightfoot cabinet in Durham Cathedral. What I discovered was an absolute gold mine of unpublished (but also unfinished) Biblical commentaries by Lightfoot—one on Acts, one on 2 Corinthians, one on 1 Peter, one on the Gospel of John and many other valuable unpublished essays on the New Testament.

Lightfoot was a once-in-a-century scholar. As a language expert, he knew the whole corpus of ancient Greek, Hebrew and Latin literature. He was also the greatest historian of the New Testament and early Christian era. Furthermore, he was an expert in the Greek and Latin Classics. In addition to all of that, he was the greatest text critic of his era. When it came to figuring out what the earliest and most authentic readings were for this or that verse, Lightfoot had no equals. He wanted a total revision of the Authorized Version (King James Version) because it was so full of later readings, not the exact words of the original authors.

This is a story not just about discovery—but a story with a happy ending. All too often, when a great discovery is made, a full and accurate reporting of the data shows up only much later (think of the Dead Sea Scrolls) and only in technical journals, not readily accessible to the general public. Happily, beginning 071 in the fall of 2014, InterVarsity Press has agreed to publish three hardback volumes of some 1,500 pages of Lightfoot’s manuscripts. The volumes will include pictures of the original handwritten manuscripts I have spent all year deciphering. We are calling the volumes The Lightfoot Legacy.

These volumes do not merely recover lost interpretations of the Bible that might be of purely historical interest. What they show is that Lightfoot was at least a century ahead of his time in terms of text criticism, historiography, the use of epigraphic and inscriptional evidence to derive the meaning of words, and pure language skills. He provided a devastating critique of radical German criticism of the Bible. Furthermore, more than a hundred years before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Lightfoot was talking about the influence of the Essenes on early Christianity. Stay tuned, more light on Lightfoot is dawning.

When we think of archaeology, we think of digging in the ground—of trowels, spades, measuring lines and the like. We think of hot sweaty work in the sun during the summer digging season. While this image is certainly a prevalent and correct one up to a point, at its core archaeology is about studying ancient cultures by what they have left behind. This brings me to the subject of text archaeology—the study of unknown, lost or missing texts. Texts, like the famous Codex Sinaiticus, are often discovered in existing buildings. The Codex Sinaiticus was discovered in St. Catherine’s Monastery […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.