There’s another, hidden Jerusalem—a place of secluded courtyards, rich with the history of many peoples. It’s even near the city center. As the great Holy Land geographer George Adam Smith observed: “Among alien and far away races the sparks were kindled of a love and an eagerness for the City almost as jealous as those of her own children.”1 One of these “far away races” was the Russians, and it is their compound that we will explore.

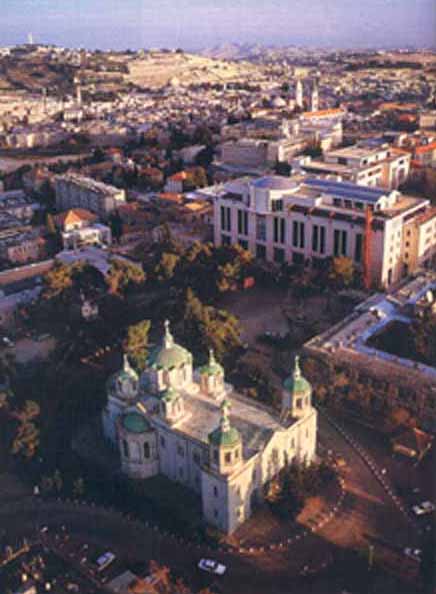

Jerusalem’s expansion outside the Old City walls began in 1860, when Sir Moses Montefiore, an English Jewish philanthropist, built two rows of apartments to the southwest called Mishkenot Sha’ananim (“the Homes of the Blessed”), to house Jews who had been living in unsanitary conditions inside the city walls. That same year, the Russian government built a consulate, a cathedral and a number of hospices for Russian pilgrims within a compound on a flat hilltop near the Old City’s northwestern corner. This hill is where the Roman legions encamped during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 C.E., which effectively ended the First Jewish Revolt.

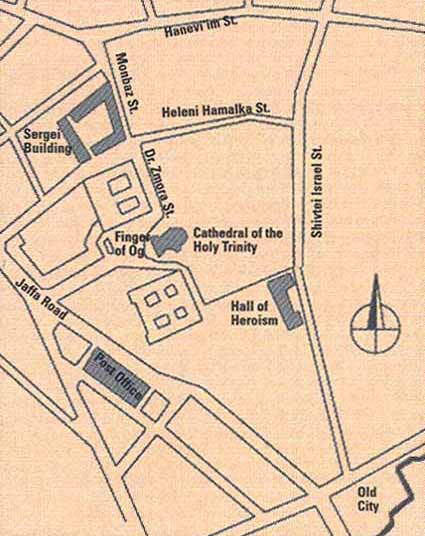

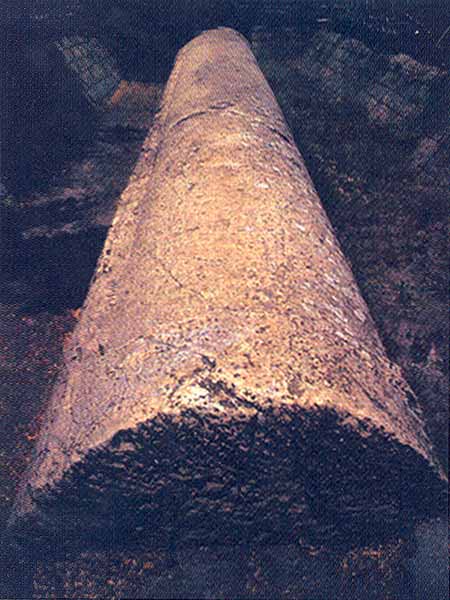

The hill is dominated by the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, but before investigating this and the other nearby pieces of pre-Revolutionary Russia frozen in time, take a moment to examine the “Finger of Og.” Lying between the cathedral and the police building, this anachronistic feature is a first century C.E. column intended for the Temple rebuilt by King Herod the Great, known in Jewish tradition as the Second Temple. The dimensions of the column are similar to those in that Temple as described by the first-century Jewish historian Josephus. Herod is believed to have quarried this area for his edifice. Since the area is 125 feet higher than the Temple Mount more than a mile away, huge stones like this would have been moved downhill. But this 50-foot-long column is still attached to the bedrock. During quarrying, the workmen apparently noticed a natural fissure in the column that made it unsuitable, so they abandoned the half-quarried column where it lay. The “Og” of the column’s nickname is the giant King of Bashan, whose bed, Deuteronomy 3:11 tells us, was nine cubits long (about 14 feet)!

Looking around, you could easily think you were in the Kremlin in Moscow. Above you looms the Holy Trinity Cathedral, the centerpiece of the 19-acre Russian Compound. With its white stone facade and bronze-capped domes, it is similar to the cathedral in the Kremlin. The bells in the two octagonal bell towers on either side of the facade were brought to Jerusalem in 1856, and were the first to ring out over Jerusalem since the Crusader period. Until then, the Turkish government didn’t permit the sound of church bells.

The area of the Russian Compound was purchased by Czar Alexander II after the Crimean War, when Russian pilgrims flocked to the city. They had an intense desire to see the Holy Places; they also wanted to obtain religious tokens with which to be buried. Miserably poor and exhausted by the overland journey from Russia, they at times filled the four hospices inside the originally walled compound to their combined capacity of more than 1,000. This enormous establishment, which also included a Mission building and an office for the Russian consul, was opened in 1864.

Apart from the cathedral and the southern wing of the Mission building, the compound has been acquired by the Israeli government and now houses law courts, police headquarters and parts of the Hadassah Medical School.

The best place to absorb the atmosphere of this preserved fragment of Czarist Russia is the Sergei Imperial Hospice—named after Sergei Romanov, the son of Czar Alexander II—on Heleni Hamalka Street. If the center of the Russian compound evokes the Kremlin, the two-story Hospice is reminiscent of 19th century St. Petersburg, where sleeping rooms, a dining hall and chapel enclose a central courtyard. Now beautifully landscaped with low trees and bushes and carved stone benches, this courtyard makes for an ideal rest spot. Interspersed among the vegetation are curious-looking instruments. The presence of this exhibition of agricultural implements is explained by the fact that the offices of the Ministry of Agriculture are now housed here, as is the office of the Society for the Protection of Nature.

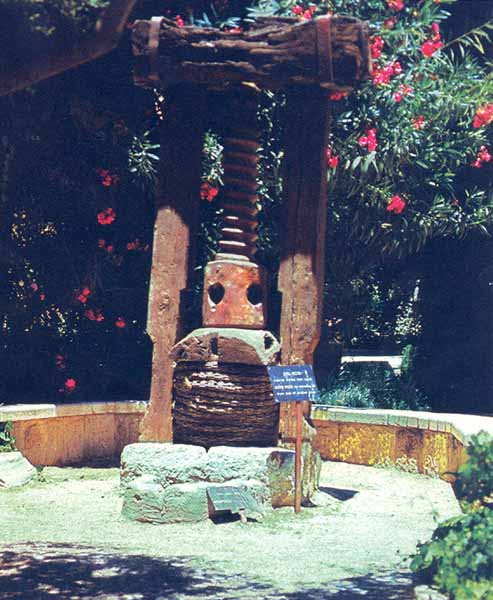

Exhibits related to olive oil production are grouped around a silver-leafed olive tree. One installation shows how olives were crushed by a stone wheel that was rotated over a stone basin, called the yam or “sea.” In a large wooden oil press, you can see how crushed olives in porous baskets were piled up between the two legs of the press and compressed with a massive wooden screw; the oil ran into a stone basin beneath.

The next bay is devoted to grinding and water-drawing. A hand-turned corn mill and quern-stones illustrate the processes involved in flour production. But the installation that most fascinates visitors is the Archimedes Screw. By turning a handle on top of this large screw, which lies inside a closed wooden cylinder, a large quantity of water can be drawn up from a lower level to a higher level. Tools such as this have been used in Egypt, most notably for drawing water from the Nile to irrigate the surrounding fields, from the Hellenistic period until today.

Normally, archaeological discoveries consist of buildings—from humble dwellings to royal complexes—together with such small paraphernalia of daily living as coins and pots. Here, though, the visitor can feel how people lived and interacted with their environment, and how they acquired the staples of their diet—oil, flour and water. Most of these implements date from after the Second Temple period (or are reconstructions). Some are still used in small, isolated communities in the Middle East.

You can also get a feel for the period of the British Mandate here. On the southern side of Heleni Hamalka street, you can still see the evidence of the horrors of the time in 1947 when this area was transformed into the center of British rule and nicknamed Bevingrad, after the unpopular British foreign secretary Ernest Bevin. Railings and barbed wire line this side of the street, a remnant of the huge fortification thrown up around the area in response to Jewish underground activity.

Another moving reminder of that period is the Hall of Heroism, reached by following a path that leads south from behind the Cathedral. When the compound was first built, this building was a hostel for Russian women. Its next incarnation was as the British Mandatory Central Prison. Now it‘s a museum displaying the cells and execution chambers used against the Jewish underground, together with an exhibit of memorabilia relating to the former prisoners.

Before taking your leave of this vast expanse, whose buildings dominated the Jerusalem skyline until a century ago, stand next to the “Finger of Og” and look around you. It’s a panorama that sweeps from Herod the Great on one side to the romantic turret of the Sergei building with its reminders of tenacious agricultural communities, up to the newly bronzed domes of the Russian cathedral and over to the barbed wire remains from the British Mandate—a panorama covering more than 20 centuries, all viewed from the heart of a modern city.

Travel Essentials

You can easily get to the Russian Compound from Jerusalem’s main Post Office on Jaffa Road, which is served by several bus routes. Cross the road and walk west, away from the Old City. Taking the first right leads you onto Cheshin Street and into the compound.

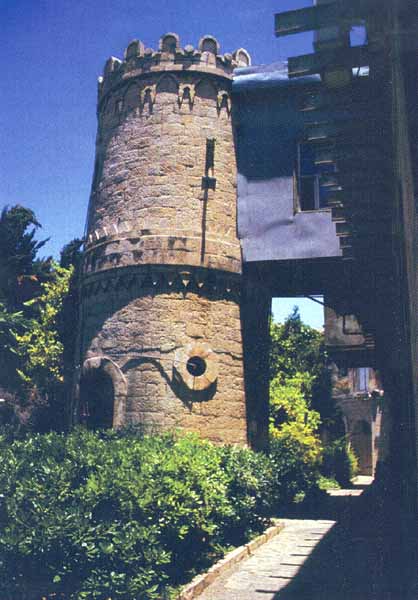

Rest Stop

If you would like an atmospheric spot to freshen up, ask at the gate of the Sergei building. You will be directed to a round tower on the right hand side of the entrance to the courtyard. Pause outside and look up at the graceful circular structure ornamented with stone diamond- and triangle-shaped reliefs and crowned with turrets. Here, without any difficulty, you can transport yourself back into the persona of a 19th century Russian pilgrim, deeply grateful for the shelter provided in this hospice.

Shopping

Take the opportunity to browse one of the country’s best selections of maps and guide books in the shop that forms part of the office of the Society for the Protection of Nature, in the courtyard of the Sergei Building. Their off-the-beaten-track tours of the country are also well worth investigating.

Food and Drink

If, after you have left the Russian Compound, you pass up the Yemenite falafel shop on Hanevi’im Street, it is your great gastronomic loss. This is the home of the best falafel in Jerusalem, where city residents of all ages converse animatedly while smothering their falafel (fried chick pea patties served in pita bread or flatbread) with the traditional accompaniments: tahina, a creamy paste made of ground sesame seeds, lemon juice and garlic; zhug, a Yemenite specialty considered good for blood circulation, prepared with fresh coriander chopped with hot peppers and spices; pickled gherkins; and salads prepared with whatever is available in season. (Tel: 02–6242346)

But if you just can’t look at another falafel you can always dine in the Hanevi’im Restaurant on 54 Hanevi’im St., just up the hill from the Yemenite falafel shop. This kosher restaurant specializes in fish and dairy cuisine. The Presto Espresso Sandwich Bar, located in the same complex, offers light meals on a spacious verandah. (Tel: 02–6247432/3)