Field Notes

010

Desert Armada

In Upper Egypt, a 1st Dynasty king was laid to rest with his favorite fleet

The desert sands of Abydos, Egypt, 300 miles south of Cairo, have revealed an improbable ancient secret: A pharaoh from the 1st Dynasty (2920–2770 B.C.) was interred with a fleet of 14 full-size boats to help him navigate through the afterlife.

Unlike mortuary models from other pharaohs’ tombs, these 60- to 80-foot vessels discovered by archaeologists from New York University, Yale University and the University of Pennsylvania are fully operational.

Not only that—their wooden plank construction represents a major advance over earlier boat-building techniques. Although human beings had mastered the construction of rafts, dugouts and reed vessels thousands of years earlier, planked boats required techniques that simply weren’t developed until the rise of early Egyptian civilization. Wood, a rare commodity in ancient Egypt, had to be shaped with stone tools. Thick planks were lashed together by rope fed through mortises and made watertight by reed caulking. As many as 30 rowers would have been needed to propel each boat.

In 1988 the American team, headed by David O’Connor of New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, noticed parallel lines of mud bricks protruding from sand mounds near mortuary monuments in Abydos (above). Preliminary excavations revealed that the whitewashed bricks formed boat shapes, and that several had a small boulder placed as a sort of anchor near the prow or stern. A few probes determined that these graves did indeed contain wooden boats, but the archaeologists saw no evidence that any of the boats had actually been used in water. As O’Connor put it, “Would you give a king a used boat?”

Because the hull of one of the boats had been exposed to the elements in 1991, a decision was made last summer to excavate that vessel to determine how best to preserve the remains of the other boats. The team uncovered wooden planks, reed matting and rope in the midsection of the buried boat. In many parts of the hull, the wood had been eaten away by wood-eating ants—whose excrement, curiously enough, preserved the original hull’s profile. Near one of the boats, the archaeologists also recovered more than 30 pottery jars typically used to transport beer.

Work goes on. These boats, preserved in Egypt’s sands, are sure to tell us much about boat-building techniques, as well as how such boats were used. Perhaps some day—from new burial goods, or from seal impressions on the beer jars’ stoppers—we will even learn the name of the pharaoh entombed here.

011

Ovid’s Love Nest

Exiled for life to the Black Sea, the Roman poet Ovid (43 B.C.–17 A.D.) wrote lovingly of home. In his Epistles from Pontus, the poet of love and change described his country house on a pine-covered hilltop near Rome, “overlooking the juncture of the Flaminia and Clodia roads.” Now archaeologists are unearthing a riverside pavilion that they believe was once part of the hortus (garden or country retreat) where Ovid relaxed among flowers, vineyards and groves of olive and fig trees.

Born in the mountainous Abruzzi region of central Italy, Ovid rose to fame around 25 B.C. by publishing his cheerfully scandalous and probably autobiographical book of love poems, Amores. He later wrote Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love), around 1 B.C., and the Metamorphoses, a collection of classical and Near Eastern tales that he likely continued to revise until his death. In 8 A.D. the emperor Augustus sent Ovid into exile on the Black Sea, where he died some years later.

Why the exile? That question has haunted historians for centuries. Some scholars have recently argued that Ovid was punished for being the lover of Augustus’s wife. Another explanation is that Ovid’s irreverence contravened the emperor’s edict making adultery a criminal offense. In 2 B.C., for example, Augustus’s own daughter was banished for adultery, and in 8 A.D.—the year of Ovid’s exile—Augustus’s granddaughter was banished as well.

The topography around the pavilion has convinced archaeologists that this is the site of Ovid’s hortus. The hill is small, rising between the two roads approaching Rome from the north—exactly as Ovid described. One road ambles alongside the Tiber for several hundred yards, so that the country retreat would have overlooked the river. Indeed, from the pavilion one can see the Milvian Bridge (109 B.C.), which Ovid also described. In 1828 Italian archaeologist Giovanni Antonio Guattani identified this hill as the site of Ovid’s hortus. In 1944 the director of the British School in Rome, Sir Thomas Ashby, identified seven Roman-period pilasters on the site as part of a cistern that would have provided irrigation water to orchards and vineyards during the long, hot Mediterranean summers.

During the 1950s the hillside with its handsome views was taken over by building speculators; today it is a nearly solid wall of apartment buildings. There remained only one relatively undeveloped space, overlooking a shanty-like strip of small workshops.

These workshops were torn down last year. Then a survey excavation was begun in April 2000. According to Gaetano Messineo, the Italian superintendent of archaeology for the area, the team found “several rooms … clustered around a core of hydraulic elements.” One room is decorated with an elegant black and white mosaic floor. At its center, surrounded by a ring of rosettes, is a colorful depiction of a very wrinkled man, identified as Silenus, who wears a crown of leaves on his bald pate (photo above).

A colonnade would have run along the front of the building, overlooking the river. Traces of lead plumbing suggest that the hortus had a fountain that supplied water to a dining room. “[These finds] tell us that even after Ovid died in exile,” Messineo said, “the residence maintained the splendor of the years when we believe that he lived there.”

Much of the ancient complex still lies buried beneath a busy thoroughfare, however, and a new municipal building is planned for the site. Perhaps the most we can hope is that the municipal building preserves some of the site.

012

Wine, Aphrodite and a Stalagmite

What better evidence of an ancient Illyrian fertility cult?

In a cave on Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast, archaeologists have discovered three chambers that probably once served as a temple for an ancient Illyrian fertility cult.

No one knows for sure where the Illyrians came from, but they were living in the northern Balkans around 6,500 B.C., when the earliest permanent settlements began appearing in the area. To the ancient Greeks, the Illyrians were simply barbaric northern neighbors.

Tim Kaiser of Canada’s Royal Ontario Museum describes the Illyrians as a loose federation of tribes, who farmed, fished and fought other people’s wars as mercenaries. The Illyrians also made money by virtue of their location on the eastern Adriatic coast; merchants or travelers heading northwest over the Alps or east across the Danube had to pass through Illyrian territory, at a price. The Illyrians were thus in continual contact with Greek and Roman civilizations—from whom they borrowed their scripts (first Greek, then Latin) to write their own Indo-European language.

For the past decade, Kaiser and Staso Forenbaher of the Croatian Institute for Anthropological Research have been exploring Neolithic remains at the Nakovana cave near Dubrovnik. In 1999 they noticed that bats were mysteriously disappearing into the back of the cave, which they thought had been completely blocked by a rock fall. Upon further investigation, they realized that this barrier was a man-made wall. Last year they returned to the site to do some exploring.

Beyond the wall were three natural chambers, which appeared to have been untouched for millennia. Pottery (above) dating from 6000 B.C. to 50 B.C.—mostly drinking vessels—lay scattered across the chambers’ floors. On the walls were Illyrian inscriptions (in Greek script) praising Aphrodite—suggesting to Kaiser and his colleagues that these chambers had once been the center of some cult.

The most convincing evidence of an orgiastic cult, however, comes from the cave’s central chamber: A 2-foot-high stalagmite, unmistakably phallic in shape, stands in the middle of the 165-foot-long corridor (above). The stalagmite had formed in another part of the cave and been moved to the central chamber, Kaiser told Archaeology Odyssey. Kaiser suspects that the phallus was placed there to catch rays of sunlight during solstices, as was done in other ancient temples. Near the stalagmite was a trough running the width of the cave and covered with limestone slabs, presumably serving as a bench. There was also a 3-foot-deep pit, which was probably used to hold water or oil.

Why were these chambers blocked up? Did the Illyrians themselves seal them to keep the cult’s secrets out of Roman hands? According to Kaiser, no one knows why the rooms were sealed. Perhaps it was done by innocent shepherds, he suggested, who wanted to keep their flocks from disappearing into a no-longer-used cave.

013

Señorita Skull

The head of a Spanish-British woman reconstructed from a 1,700-year-old skeleton

Around 1,700 years ago, a deceased young woman was placed in a lead coffin, which was set in a large stone sarcophagus. Her left arm was folded across her body, glass perfume bottles and jet-black jewelry were arranged beside her. A funeral shroud with gold thread was placed over her body. Then the sarcophagus was sealed and lowered into a grave in a cemetery outside the walls of Roman London.

In March 1999 British archaeologists exhumed the woman’s body, still at rest in the lead coffin inside the stone sarcophagus (see Recent Finds, Field Notes AO 02:04). They found that the woman had died in her 20s, of unknown causes, even though she was well nourished and apparently in good health. She may have been Christian—since her left arm was laid across her body, in Christian fashion, and her grave was oriented east-west. At least, she was from a wealthy family, one that could afford an expensive lead coffin and a gold-threaded funeral shroud.

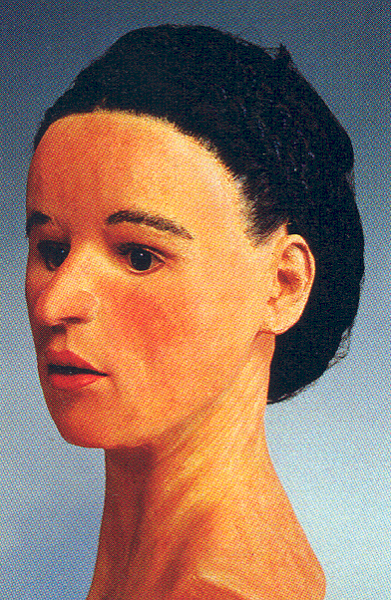

But what did she look like? Londoners got their first glimpse last year, when a reconstructed bust of the young woman (above) was put on display at the Roman Gallery of the Museum of London.

Caroline Wilkinson of the Unit of Art in Medicine at Manchester University used a combination of forensic science and sculptural modeling to resurrect the ancient noblewoman. The technique, originally developed to recreate the faces of unidentified crime victims, begins with the making of a plaster cast of the skeleton’s skull. The facial muscles, along with the nose and mouth, are modeled in clay and molded to the plaster cast. Then another layer of clay is added to re-create the face’s soft tissue, such as the skin. Finally, this plaster-clay model is cast in wax, which is then painted.

More detective work and some informed guesses were required to render the woman’s eyes, hair and skin. Paul Budd, a researcher in the Department of Archaeological Services at the University of Bradford in West Yorkshire, determined that some of the lead in the skeleton’s tooth enamel came from the southwest Mediterranean region. The woman’s family probably moved to Britain from Spain when she was eight to ten years old. So the wax portrait bust was given rich dark hair and olive skin.

The stone sarcophagus, coffin, skeleton and wax portrait bust are all on permanent display at the Museum of London’s Roman Gallery.

011

OddiFacts

Tradition

Feel like eating Greek tonight? Archaion Gefsis (Ancient Tastes), a new restaurant in downtown Athens, is trying to make the experience a bit more authentic. The restaurant’s owners, Yannis and Suli Adamis, researched ancient recipes for two years to develop a menu that would be as close as possible to what Sophocles and Alexander actually ate. The entrées include piglet stuffed with goat liver, offal sausages and cuttlefish grilled in ink. (No sugar, tomato, rice or lemon here!) The restaurant does have its critics, however. Some point out that we cannot re-create ancient Greek cuisine with any exactitude, since we know little about the spices used. Others decry the restaurant’s toga-wearing waiters (ancient Greeks wore tunics). Even so, Ancient Tastes has a loyal following, and the owners plan to open several new franchises.

Desert Armada

In Upper Egypt, a 1st Dynasty king was laid to rest with his favorite fleet

The desert sands of Abydos, Egypt, 300 miles south of Cairo, have revealed an improbable ancient secret: A pharaoh from the 1st Dynasty (2920–2770 B.C.) was interred with a fleet of 14 full-size boats to help him navigate through the afterlife.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.