Forgery Hysteria Grips Israel

052

Ivory Pomegranate and Other Antiquities

A “forgery hysteria” is consuming archaeological circles in Israel at the moment. The characterization is that of Johns Hopkins professor Kyle McCarter, a leading American paleographer (an expert in ancient scripts). On a recent trip to Israel, I talked to that country’s leading paleographer, Hebrew University’s Joseph Naveh, and to the co-editor of the Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ), Shmuel Ahituv, who teaches at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beer-Sheva. Both agree with McCarter’s characterization. That doesn’t mean that everything that has been questioned is authentic—or that everything that has been declared to be a forgery is a fake. But it does mean that almost everything is the object of suspicion and question—even some objects that have supposedly been professionally excavated. And the rumors circulating about distinguished scholars are nasty.

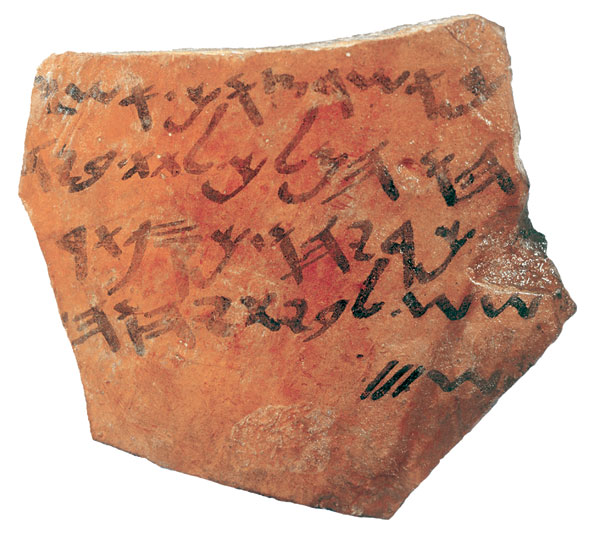

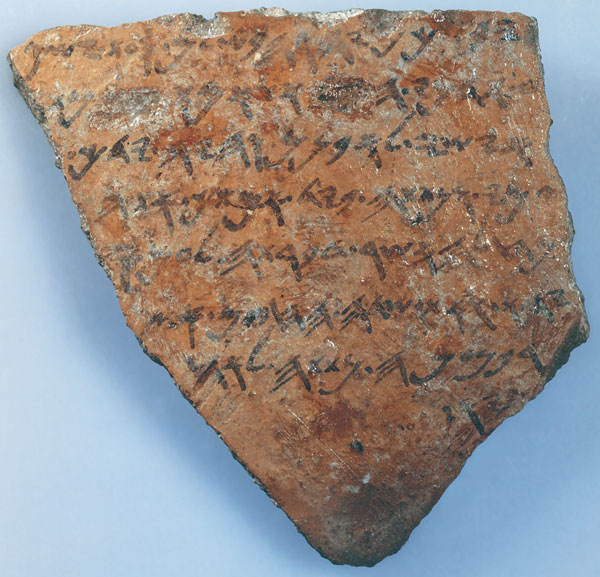

The latest supposedly ancient inscriptions to fall from grace are two ostraca—pottery sherds used in ancient times as notepaper—that were described in BAR articles several years ago.a One records a contribution of three shekels to the Solomonic Temple. The other is a widow’s plea for a part of her late husband’s estate. Both ostraca are owned by Shlomo Moussaieff of London and Herzliya, Israel, and are often referred to simply as the Moussaieff ostraca. In an article in the most recent issue of the Israel Exploration Journal, they are declared to be “without a doubt,” modern forgeries.1

The senior author of the article, Yuval Goren, a petrologist at Tel Aviv University, has been the key figure in every one of the recent forgeries unmasked in Israel. The researchers studying the two ostraca found a layer of wax over the inked inscription. The forger put the wax over the letters, the report says, “to prevent dissolution of the letters by water.” No consideration is given to the possibility that the paraffin was applied to an authentic inscription as part of the conservation process, a common technique. The real clincher, however, is the same isotope argument used to unmask the alleged forgery of the James ossuary inscription, which reads, “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus.” Except that here the authors rely on carbon as well as oxygen isotopes in the patina, concluding that it “could not have formed naturally under typical climatic conditions and water composition in the above-geographical zones within the last three thousand years.” Again, however, no consideration is given to whether there could be an innocent explanation for the isotope ratios they found. The owner of the ostraca had them examined by two laboratories that found nothing to arouse suspicion. The team led by Goren did not deal with, or even mention, these other studies.

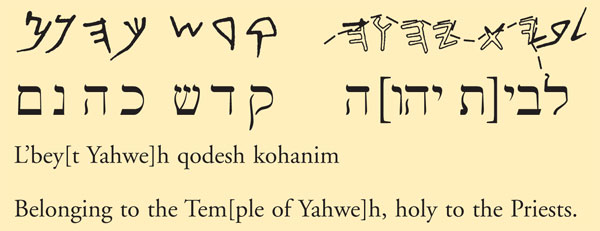

Another article in the same issue of the Israel Exploration Journal deals with the famous inscription on a small ivory pomegranate that reads, “(Belonging) to the Temp[le of Yahwe]h, holy to the priests.”2 As previously announced by the Israel Museum, which paid $550,000 for the object in 1988, the inscription is a modern forgery. Unlike the analysis of the Moussaieff ostraca, which does not deal with the script (paleography), the article on the pomegranate inscription does deal with the writing in addition to an analysis by material scientists.

Paleographically, the pomegranate inscription includes one “problematic” letter, the mem. However, the two paleographers among the authors (Ahituv and Bar-Ilan University’s Aaron Demsky), whom we assume contributed this analysis to the report, recognize that it might represent nothing more than “a slip of the engraving tool, as well as by its [the pomegrante’s] small dimension.” It is also true that the engraver was not working on a flat surface but around the neck of a curved object, which may account for the “problematic” nature of this letter. Ahituv and Demsky also find the syntax of the inscription “awkward.” In addition, the words of the inscription are not separated by the usual dot (or, in even in earlier times, a vertical line). Ahituv and Demsky acknowledge, however, that some ancient Hebrew inscriptions are without either of these word dividers. Inscriptions without one of these two word dividers are written, to use the scholarly language, scriptio continua. Nevertheless, Ahituv and Demsky found it “unlikely” that the engraver would have omitted the customary word dividers.

They recognize that from the paleographical viewpoint “there seems little to add to the thorough discussion of [the inscription by Nahman] Avigad,” who before his death in 1992 was Israel’s leading script expert. “I am fully convinced,” Avigad wrote shortly before his death, “of the genuineness of the ivory pomegranate [and] the authenticity of its inscription … The epigraphic evidence alone, in my opinion, is absolutely convincing.”3 Avigad’s conclusion was the same as Sorbonne professor André Lemaire, who wrote an article in BAR on the pomegranate inscription.b Lemaire continues to believe that the inscription is authentic, as do other scholars, includiing McCarter.

I spoke with both Ahituv and Demsky about their conclusion. I asked each of them how certain they were, on a scale of 1 to 053100, that the inscription was a forgery. Each thought for a while. Ahituv finally decided the likelihood that it was a forgery was between 80 percent and 90 percent. Demsky chose the higher figure. For neither was it 100 percent.

Ahituv himself offered that this was not enough to convict someone criminally. A criminal conviction is justified only if there is no reasonable doubt as to whether the item is a forgery.

Ahituv also said that there are parts of the IEJ report (written by the material scientists) that even he does not understand. However, that the inscription is declared to be a forgery by “real” scientists cannot help but affect the judgment of outsiders who must respect the “scientific” results. Professor Ahituv himself told me that before he saw the inscription under the microscope, he was not sure it was a forgery. It was what he saw under the microscope that convinced him that the chances that it is a forgery are somewhere between 80 and 90 percent. In the end, it was the hard scientists who determined his vote. But he was on the committee not as a member of a jury (to vote on all the evidence), but as an expert to determine whether his own expertise, not someone else’s expertise, enabled him to make the determination. He knew about the “problematic” mem, the awkward syntax and the absence of word dividers before he looked in the scientists’ microscope, but these infirmities did not stop him from including the pomegranate inscription in his Handbook of Ancient Inscriptions without raising even a question as to its authenticity.

What makes some observers uncomfortable is that no outside material scientists have reviewed the work of Yuval Goren and his regular colleagues on the committee. This is especially troubling because this same team of material scientists, led by Yuval Goren, is responsible for unmasking all the recent forgeries in Israel. And their work in some of these cases has been heavily criticized by other scientists—including several from Israel’s Geological Survey (Shimon Ilani, Amnon Rosenfeld and Michael Dvorchek), a professor at Tel Aviv University (Joel Kronfeld), a Royal Ontario Museum scientist (Edward Keall) and by James Harrell, of the University of Toledo and the secretary of the Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (ASMOSIA). (To find Harrell’s recent critique of the pomegranate analysis, see “On the Web”.)

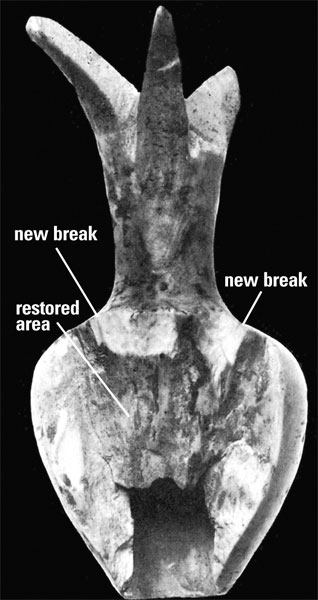

To a layperson, it seems strange that the alleged forger is both extremely smart and well informed, and at the same time extremely stupid. For example, according to the hard scientists, led by Goren, the pomegranate was broken in antiquity—a third of it is missing. This means the forger chose to engrave an inscription (accomplished with extreme skill) on a broken pomegranate. That is, the part of the neck of the pomegranate where the words “(Belonging) to the Temple of [Yahwe]h” (the personal name of the Israelite God) would go is missing. The Hebrew letters are LBYT [YHW]H. The letters in brackets are not there at all; they have been reconstructed by modern scholars. The letters in italics are only partially there.

According to Goren’s analysis, there are three new breaks (or missing parts) on the broken side of the pomegranate’s grenade. One of these three pieces that broke off was glued back on. No explanation is given for this.

054

According to Goren’s scenario, the forger decided to carve an inscription on the shoulder of a broken pomegranate, one-third of which was already missing, even though the inscription would go through the missing part of the shoulder!

Here is how the forger proceeded, according to Goren. First (reading right to left—this is Hebrew), he engraves the LB of “(Belonging) to the Temple of Yahweh.” Then part-way through, as he is carving the next letter, Y, he comes too near the old break—and accidentally breaks off another piece of the pomegranate. So he has to finish as much of this letter as he can on what remains, but this time without coming to the edge of the old break.

Most of the area where the next letter (T) would go has now been knocked off, so the forger engraves just the top of the T, but without going up to the old break, fearful of having another accident like he did with the Y.

The forger then proceeds to engrave the next word (YHWH), beginning with Y. Oops! The damn thing breaks again, knocking off another piece so big that we see no trace whatever of the Y. This forger doesn’t seem to learn. Indeed, the part that breaks off is so big that there is simply no space on which to carve any of the Y or the next two letters, H and W. There isn’t even space to carve all of the final H. So the forger engraves just the very top of that letter. But, having made the same mistake twice, he is now careful not to go up to the edge of the old break and knock off even more of this precious object.

Maybe it happened this way, but if it did, I would say the forger is a little dopey, rather than the “sophisticated” rogue he is alleged to be by the team that thus unmasked him. I would be more comfortable, frankly, if this scenario were confirmed by independent experts, someone other than the same man (actually, the same team of material scientists) that has unmasked every one of the recent alleged forgeries in Israel.

One of the other things that also makes me suspicious is that the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) announced to the press as early as summer 2004—before studying the pomegranate inscription and before a committee was appointed to study it—that the inscription was a forgery! The IAA made this judgment simply by looking at the pomegranate through the glass case in the Israel Museum. How do I know this? Because after the press reported that the IAA had found the inscription to be a forgery, I called Israel Museum director James Snyder, who told me he knew nothing about it—except what he read in the newspaper. The IAA had not come to him to request an opportunity to examine the pomegranate. Snyder attributed the IAA announcement as, in effect, a publicity stunt, as “a platform for publicity.” At that time Snyder defended the inscription as authentic. We reported all this in our July/August 2004 issue (p. 52), which went on the newsstands in mid-June and which closed in mid-May.

In short, it appears that someone decided even before looking at the pomegranate inscription outside of its case that it was a modern forgery.

At this point no layperson can declare with certainty that the pomegranate inscription is authentic or a forgery. There is a clash of experts. But the one thing I came away with from my recent discussions in Israel is that when it comes to questions of forgery versus authenticity now consuming Israeli scholars, there are three possible conclusions, not two. The first possible conclusion is it’s (whatever “it” is) a forgery. The second is that it’s authentic. The third possibility is that it’s uncertain.

056

Professor Naveh explained to me his own position with respect to unprovenanced inscriptions (inscriptions that come from the antiquities market). Before he will publicly declare an inscription questionable, he must be able to explain his reasons. He will not base his condemnation simply on a hunch. On the other hand, if he intuitively finds something to be suspicious, he will not rely on it in his research.

This of course raises the issue as to whether unprovenanced objects should be published by academics. It is a hot topic. Both the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) and the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) will not permit the publication of unprovenanced finds in their journals. Yet almost all senior scholars who are expert paleographers do publish such finds. As the eminent Swiss scholar Othmar Keel stated in our last issue: “I don’t think we can write a history of the ancient Near East without relying on unprovenanced material.” When I raised the question of publishing unprovenanced material with Professor Ahituv, he responded, “Should we throw all unprovenanced material in the garbage? Stupid!”

Professor Ahituv is co-editor of the Israel Exploration Journal, which, until the recent forgery hysteria, regularly published articles about items that had come from the antiquities market. But according to the highly respected, powerful and long-time administrative editor of the journal and director of the Israel Exploration Society, Joseph Aviram, the question of publishing unprovenanced finds is being rethought by the journal. Aviram would confine the journal to publishing only artifacts that come from professional excavations.—H.S.

On the Web

For a thorough scientific critique of the report recently published in the Israel Exploration Journal concluding that the ivory pomegranate inscription is a forgery, see “Goren’s Pomegranate Analysis: Sloppy Science and Flawed Reasoning,” by James A. Harrell, University of Toledo, at www.bib-arch.org under “Finds or Fakes?”

Should Scholars Look at Finds that May Have Been Looted?

More and more leading scholars are speaking up in opposition to the policy of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) and the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) that forbids consideration of unprovenanced objects in their publications or at their meetings. Unprovenanced objects are those without a known history of their site of discovery, having simply appeared on the antiquities market. Many of them are undoubtedly looted. But they may nevertheless impart significant information about ancient life.

Robert Merrillees, former Australian ambassador to Israel, a scholar specializing in Cypriot archaeology and former director of the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute (CAARI), the ASOR school in Nicosia, recently defined the debate over unprovenanced antiquities and gave his judgment of the ASOR/AIA position:

The issue of unprovenanced antiquities has in recent years become not only a serious challenge to academic research but an ethical and political battleground which has divided the archaeological community. On the one hand, the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) and the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) have taken it upon themselves to ban from their own publications all studies of artefacts without a legitimate pedigree, and to boycott other publications which, in their view, promote the illicit antiquities trade by, for example, including in their copy advertisements for the sale of ancient objets d’art. This policy is based on the assumption that all antiquities without proven provenance potentially come from unauthorized digging and that unilateral action by concerned organizations will stem the flow of illegally exported items and so discourage looting. King Canute had the same idea.4

Merrillees made the remark in a review of the works of two scholars who utilized unprovenanced objects in their research. The author of one of the works, Stella Lubsen-Admiral, and the editor of the series in which it appeared, Professor Paul 058Astrom, have, Merrillees wrote, “by the AIA’s and ASOR’s standards, joined Professor Vassos Karageorghis, Professor J.D. Muhly and the reviewer in that gallery of ‘rogue’ archaeologists whose work, according to Dr. Ellen Herscher [of the AIA and ASOR], ‘will serve to stimulate the antiquities market in general and encourage further looting.’”5

The people mentioned by Merrillees are not the only scholars who have joined the ranks of “rogue archaeologists” as defined by ASOR and AIA standards. In our previous issue (July/August 2005), we published an interview with Othmar Keel, the distinguished Swiss historian of religion, who has also joined these ranks. In France the list includes André Lemaire and Pierre Boudreil. In Italy it includes Felice Israel and Mirjo Salvini. In England it includes W.G. Lambert and Dan Levene. In Germany it includes Martin Heide. In Switzerland it includes Christoph Uehlinger, as well as Keel. In the United States, the increasing—and increasingly vocal—throng includes Harvard’s Frank Moore Cross, John Hopkins’s Kyle McCarter, Boston College’s Philip J. King, Meir Lubetski of City University of New York, and Gratz College president Jonathan Rosenbaum. And in Israel it includes Joseph Naveh, Shmuel Ahituv, Shaul Shaked, Bezalel Porten, Shalom Paul and Ada Yardeni, to name only a few. All are leading scholars in their fields.

Moreover, unlike ASOR’s Bulletin (BASOR) and AIA’s American Journal of Archaeology, many distinguished scholarly journals refuse to abjure unprovenanced finds in their pages. Foremost among them are the Revue Biblique, Ugarit-Forschungen and Bibliotheca Orientalis. The Israel Exploration Journal, however, is reconsidering its acceptance of articles publishing unprovenanced finds (see “Forgery Hysteria Grips Israel,” p. 52).

Frank Moore Cross: Statement on Inscribed Artifacts Without Provenience

Because of my personal relationship with Frank Cross, I wanted to be sure that my inclusion of his name among the list of senior scholars who publish unprovenanced finds, referred to in the preceding article, was not based on personal information that he would not want mentioned in print. In response, Professor Cross sent me the following statement.—H.S.

I am indeed to be included among those who think that artifacts, particularly those bearing inscriptions, should be published whether dug up in scientifically controlled excavations or dug up by plundering antiquities dealers, collectors or their minions. Inscribed artifacts have so much—I am tempted to say most—to contribute to history and culture that they dare not be discarded and ignored. Scholars should not duck the task of learning the skills to establish authenticity or forgery, the typology of script, of orthography, the typologies formed by history of grammar and lexicon, and the typology of pottery, together with examination by “hard” scientists. I should add the caveat that analyses by hard scientists are by no means infallible, and sometimes inferior to the scientific judgment of typologists. Having been a chemist early in my career, I am aware of the false results of poorly designed experiments—illustrated by the false results of scientists in the analysis of the forged Yehoash Inscription, and indeed by some of the vagaries of early carbon-14 analyses. Literary and historical critical judgments, though more subjective, must also be marshaled.

Inscriptions without provenience must be published in scientific journals, refereed journals, and the authenticity or lack thereof established over the years, and if necessary generations, as scholarly skills become more precise and (we trust) outstrip forgers. Ideally, scholars should be trained in most of the typological sciences. Alternatively, teams of specialists should be enlisted to bring together their skills to deal with inscriptional materials without provenience. The papers in the current Israel Exploration Journal on the inscribed ivory pomegranate and the two ostraca from the Moussaieff collection are exemplary cases of teams of scholars establishing inscriptions without provenience as forgeries. But to my mind there is no question that these inscribed artifacts should have been published.

To throw away inscriptional materials because they come from illicit digs (or forgers) is in my opinion irresponsible, either an inordinate desire for certitude on the part of those without the skills or energy to address the question of authenticity or the patience to wait until a consensus of scholars can be reached. It is noteworthy that those most eloquent in denouncing the publication of material from illicit digs are narrow specialists, especially dirt archaeologists. Ironically, little is said about the forgeries that are “salted” in controlled digs by pranksters or seekers of revenge for slights, or especially when hired laborers do most of the digging. There is the story of the find of an Old South Arabic inscription in the excavation of Gibeon. It read mdyr brtjrd, “Director Britjard (Pritchard).” The older practice of giving baksheesh—still existing in parts of the Levant—for every important small find by laborers creates every temptation to salt digs. In any case there is no alternative to scholars or teams of scholars gaining the skills to distinguish the authentic from the spurious.

The (inevitable) narrowing of fields and increasing specialization is no small part of the problem. Many archaeological specialists, foreign and native, digging in Israel and the Levant are untrained in the epigraphic disciplines, in the history of West Semitic languages, their grammar, lexicon and orthography, and particularly in the typology (palaeography) of their scripts. Often such specialists deal uncritically with Biblical material (I do not believe that anyone with serious historical-critical skills can suppose the Yehoash Inscription to be authentic).

There is also the question of various sorts of non-provenienced artifacts and inscriptions. There is the Rosetta Stone, the Moab Stele, mountains of cuneiform tablets and 060Egyptian papyri without any certain provenience. Their authenticity is in their content, their uniqueness, and it would be absurd to remove them from the literature. Provenience becomes a complicated category when we come to the Dead Sea Scrolls. An example is the great Samuel manuscript from Cave 4 (4QSama). Some 27 fragments of the manuscript came from the scientific excavation by Roland DeVaux of the lowest level of Cave 4. Later thousands of fragments were bought from Bedouin. Only a fool would call this purchased material without provenience and to be discarded. But what of the Samaria Papyri? Excavation of the cave in the Wâdi-ed Dâliyeh produced some fragments of fourth-century papyri, but no joins to the papyri bought from the Bedouin. Are the Samaria Papyri to be consigned to oblivion? Nonsense, they are unique in content and incapable of being forged. Further, what about the hoards of fourth-third century ostraca from Idumaea, one volume of them published by André Lemaire, another by Joseph Naveh and Israel Eph‘al? ‘They are totally without provenience, though their Idumaean origin is secured by their content. Are scholars to ignore them? Again their content and palaeography warrant their authenticity. We could go on. The hoard of 334 fourth-century Samarian coins published by the late Yaacov Meshorer is without provenience. The statements of the dealers who sold them are evidently to be ignored. Most if not all are probably from the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh. Their character, the names they bear, their motifs and their scripts, as well as their minting technique, authenticate them.

I note with regret that the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research is increasingly a journal of dirt archaeology—although I understand that some attempts at remedying this narrowing are being undertaken with the publication of an issue of epigraphic material. Happily, the Israel Exploration Journal continues a broad coverage that once marked the Bulletin. It has not established a doctrinaire policy on non-provenienced artifacts comparable to that imposed by a small cabal of officers of the American Schools of Oriental Research on its publications.

Contrary to many, I have long urged the Department of Antiquities of Israel (now the Antiquities Authority) to shut down licensed antiquities dealers. I find extraordinary the argument, especially made by museum personnel, that having licensed dealers prevents the best finds from going abroad and channels them into Israel’s museums. Anyone who has viewed the Moussaieff collection is aware that the best pieces go abroad with (or without) licensed antiquities dealers. Far better is the proposal for the Authority to sell duplicate pieces they have in great excess in their storerooms to academic institutions that wish to have study collections and to use the profits for scientific excavation and publication.

The argument is often heard that publishing unprovenienced pieces encourages more illicit digging, since publication is felt to authenticate and so increase their market value. I am not aware of any clear evidence that this is true. In any case, illicit digging will continue unabated as long as antiquities dealers and their suppliers are active. However, the establishment of the spuriousness of forged pieces will certainly reduce their value on the open market and put dealers in fakes at grave risk.—Frank Moore Cross, Harvard University

Forgery Trial To Begin: Call The First Witness

The first witness in the “forgery trial of the century” will be famed antiquities collector Shlomo Moussaieff of London and Herzliya, Israelc—or maybe not.

The criminal indictment—brought against the owner of the controversial Jesus ossuary, the most prominent antiquities dealer in Israel, the best-known restorer of antiquities in Israel and two othersd—alleges an international conspiracy whose members forged many of the most important, recently-surfaced Biblically-related artifacts. On July 7, the Israeli court granted the prosecutor’s request to promptly take Moussaieff’s testimony as the first witness. His interrogation is to begin on September 4 (two days before his 82nd birthday) and continue on four dates in November.

Moussaieff, however, hopes to avoid testifying on the basis of his medical condition.

Ironically, it is doubtful that Moussaieff has anything important—or even significant—to say. He can tell the court what he bought from whom and what he paid for the objects—if he remembers. But he is no expert; he cannot testify as to whether or not they are forgeries. More important, even if they are forgeries, it is highly doubtful that collector Moussaieff knows anything about who made the forgeries or whether his sellers knew they were forgeries at the time of the sale. And Moussaieff is on record as saying he doesn’t care whether or not they are forgeries.

It is said that history is a tragedy the first time it occurs; the second time, it repeats itself as farce. The first time, when the forgery indictment was filed, it ruined lives (if the defendants are guilty, they should have been ruined; but the power to file a criminal indictment can be lethal, whether or not the defendants are guilty). With the testimony of the elderly Moussaieff—if it occurs—the case is likely to take on the aspect of farce. According to one of the lawyers in the case, Moussaieff’s testimony may well demonstrate to the judge the sprawling weakness of the case.

More to come.

Forgery Hysteria Grips Israel

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

David Noel Freedman, “Don’t Rush to Judgment,” BAR, March/April 2004.

The Biblical text also mentions a city called Adamah (’DMH) (Genesis 10:19) ruled by King Shinab (Genesis 14:2, 8). It appears to be located in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea. It is possible that this is the same place as the city of Adam. Adamah has apparently survived in the Arabic place-name Damiah. A bridge across the Jordan is still known as the Damiyeh Bridge.

See “The Storm over the Bone Box,” BAR, September/October 2003.

Endnotes

Frank Moore Cross, “Notes on the Forged Plaque Recording Repairs to the Temple,” Israel Exploration Journal 53 (2003), pp. 119–122.

Frank Moore Cross, “Notes on the Forged Plaque Recording Repairs to the Temple,” Israel Exploration Journal 53 (2003), p. 122.

Frank Moore Cross, “Notes on the Forged Plaque Recording Repairs to the Temple,” Israel Exploration Journal 53 (2003), p. 119.