Jewish Epitaphs from Ancient Rome

024

Whenever I visit my dad’s grave at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, I inevitably find myself comparing the headstones there to inscriptions from the Jewish catacombs in Rome. On the one hand, the uniformity of headstones at national cemeteries is in marked contrast to catacomb inscriptions, whose quality, shape, and material vary widely. On the other hand, I find the relatively limited range of imagery and sentiments in each to be strikingly similar.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs gives loved ones a selection of 74 “emblems of belief” that can be used on government markers, but in the immediate vicinity of my dad’s grave, only a handful are represented. Calculating how many times each of these symbols, the phrase “beloved father,” or a quotation from the Bible are found on the graves at Fort Snelling might tell us something interesting about the people buried in a national cemetery in Minnesota. Similarly, examining the frequency with which certain elements appear in the Jewish inscriptions can tell us about the Jews of ancient Rome.

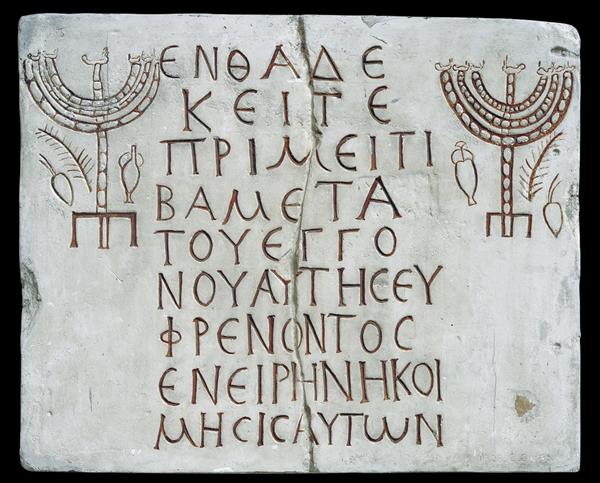

More than 600 ancient Jewish inscriptions have been identified from the city of Rome, the vast majority coming from funerary contexts. Epitaphs, or tombstone inscriptions, offer glimpses of people whose names would otherwise be lost to time. In many cases, the deceaseds’ names are all we know, such as this woman buried in the Monteverde catacomb: “Here lies Ioulia Sebera” (CIJ 352).1 This inscription, like nearly 73 percent of the Jewish epitaphs from Rome, was written in Greek.

Less than 18 percent of the Jewish epitaphs in Rome were written in Latin, including this one from the Vigna Randanini catacomb: “Aurelius Ioses [and] Aurelia Auguria placed [this memorial] for their son Agathopus, the well-deserving, who lived 15 years” (CIJ 209). In addition to Agathopus’s name, this inscription identifies the names of his parents, who survived him and were responsible for his burial, along with his age at death and the epithet “well-deserving.”

Other inscriptions were written in a combination of Greek and Latin, including some with Greek words written using Latin letters or others with Latin words transliterated using the Greek alphabet. A handful of inscriptions also include Hebrew or Aramaic elements, such as the final phrase in this inscription from Monteverde: “Here lies Sabbatis, twice archōn, who lived 35 years. In peace [be] his rest. Peace on Israel” (CIJ 397). While the commemorator who set up this inscription is not named, Sabbatis’s leadership role within the Jewish community as an archōn (“leader” or “ruler”) is noted.

As these examples show, only limited insights about an individual can be gleaned from reading his or her funeral inscription in isolation. Information is usually restricted to some combination of the following: the name of the deceased, the name of the person who commissioned the inscription, the relationship between the deceased and the commemorator, the deceased’s age at death, an identifying characteristic (such as a synagogue title), and one or more epithets.

Only a handful of the Jewish epitaphs from Rome contain all of these elements. One such example still tells us little details beyond the deceased’s marriage and his status as an archōn-designate in the Jewish community: “To Aelius Primitivus, [my] incomparable husband, the mellarchōn (“archōn-designate”), who lived 38 years, with whom I lived 16 years without any complaint. To her sweetest husband, the well-deserving, Flavia Maria made [this memorial]”(CIJ 457). 025026Financial and space constraints likely offer some explanation for why few inscriptions contain all of these elements. These are the same considerations that families today must consider, regardless of whether they are dealing with the cost of a private interment or the space limitations of a standard government headstone.

Two additional components of inscriptions also reflect deliberate choices made by the commemorators, although they shed little light on the lives of the deceased individuals: burial formulae that introduce or conclude the inscription and symbols that decorate the epitaph. Burial formulae can be as simple as the “here lies” that introduce Ioulia Sebera’s and Sabbatis’s inscriptions above. Others may give us greater insight into the beliefs and expectations of the people who set up the inscription, such as the popular “in peace [be] your rest” or the much less common “take courage, no one is immortal.”

Symbols related to Jewish rituals appear regularly, especially the menorah (lampstand), lulav (date palm frond), etrog (citron fruit), and shofar (ram’s horn). The inscription for Sabbatis includes three of these four symbols; only the lulav is missing. The distinctiveness of the menorah, which appears far more frequently than any of the other symbols, makes it easy to identify on inscriptions, even when only a fragment survives.

The limited insights to be gleaned from any one inscription are no different among the Jewish catacombs than they are at Fort Snelling, but, by aggregating data from a large number of inscriptions, we can begin to identify patterns. A quantitative analysis of the commemorative choices made for deceased loved ones opens new windows into the commemorators’ priorities, especially when compared with quantitative work conducted by previous scholars on pagan and Christian inscriptions from Rome.

A noticeable difference between these groups of inscriptions has to do with information about the person who commissioned the inscription. The inclusion of this information is quite common on pagan and Christian inscriptions from Rome, with roughly 67 percent of the former and 47 percent of the latter specifying it. In contrast, only about 23 percent of the Jewish inscriptions specify the relationship between the commemorator and the deceased.

Additional differences can be noted in the chosen epithets. Some of the epithets found on Jewish inscriptions also appear on pagan or Christian ones, such as “well-deserving” on Agathopus’s epitaph or “sweetest” on Aelius Primitivus’s. These shared epithets are found on the 23 percent of Jewish inscriptions that name the relationship between the dedicator and the deceased, where they likely reflected the relationship between these individuals.

In contrast, Jewish inscriptions with anonymous commemorators used a more diverse set of epithets, many of which are absent altogether on pagan and Christian inscriptions. Some of these are religious or ethical in nature, such as “holy” and “just,” or describe the deceased’s commitment to the synagogue and Jewish law. Others use compound adjectives beginning with phil- (“-loving”) to describe the deceased’s love for family members. Somewhat counterintuitively, these appear mostly on inscriptions where the commemorator is not named. This may suggest that they were not merely used to describe the personal relationship between the commemorator and the deceased but may have been considered ethical qualities characteristic of Jewish life and valued by the community at large.

When faced with financial considerations and limited space, dedicators were forced to choose which components to include. It is in these choices that we can identify trends in commemorative practices.2 Commemorators could choose elements that emphasized the deceaseds’ connections to family and heirs or components that highlighted their Jewish identity. These two options were not mutually exclusive, and elements of both trends frequently appear on the same inscription.

Identifying the name of the person who set up the inscription and his or her relationship to the deceased follows the first trend, as does the use of epithets shared with the pagan and Christian inscriptions. Inscribing the age at death (or some other indication of the deceased’s age), which was done for 44 percent of the Jewish inscriptions, also seems to be more in line with this first trend, since a person’s age would have had the most meaning to those who knew the deceased personally. In fact, of all the components beyond the deceased’s name, age at death is the one that appears most frequently on Jewish inscriptions.

The second trend is exemplified by the epithets particular to the Jewish community discussed above and by the inclusion of one or more Jewish symbols. These symbols appear on 33 percent of all epitaphs, making them even more common than the commemorative relationship (23 percent). Another commemorative choice that reflects this second trend is to provide a synagogue title for the deceased, such as we saw for Sabbatis and Aelius Primitivus, or for the inscription’s dedicator. These titles appear on about 25 percent of the Jewish inscriptions.

When the commemorative choices of Jews are compared to those of other residents of Rome, the most striking characteristic is the sheer number that do not name the commemorator. I would suggest that this reflects a difference in the priorities of some Roman Jews when they decided how to memorialize their loved ones. To a certain degree, the decline in specifying the commemorative relationship is likely chronological (i.e., the mentions of dedicators decline over time across the board), but the fact that the Jewish inscriptions significantly outpace the Christian ones in this trend is telling. When coupled with the prevalence of epithets that were particular to the Jewish community, Jewish symbols, and synagogue titles, we can recognize that some dedicators made choices that underscored the deceaseds’ Jewish identity, at the expense of family connection. This suggests a shift away from the commemorative relationships that pervade the broader Roman corpus and a concomitant emphasis on communal identity and values.

Whenever I visit my dad’s grave at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, I inevitably find myself comparing the headstones there to inscriptions from the Jewish catacombs in Rome. On the one hand, the uniformity of headstones at national cemeteries is in marked contrast to catacomb inscriptions, whose quality, shape, and material vary widely. On the other hand, I find the relatively limited range of imagery and sentiments in each to be strikingly similar. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs gives loved ones a selection of 74 “emblems of belief” that can be used on government markers, but in the immediate vicinity […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.