Burnt Offerings: New Discoveries from the Petra Scrolls

026

In 1993 a team of archaeologists with the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR) in Amman, Jordan, discovered a cache of 152 charred papyrus scrolls tucked away inside a building adjoining Petra’s sixth-century A.D. Byzantine church.

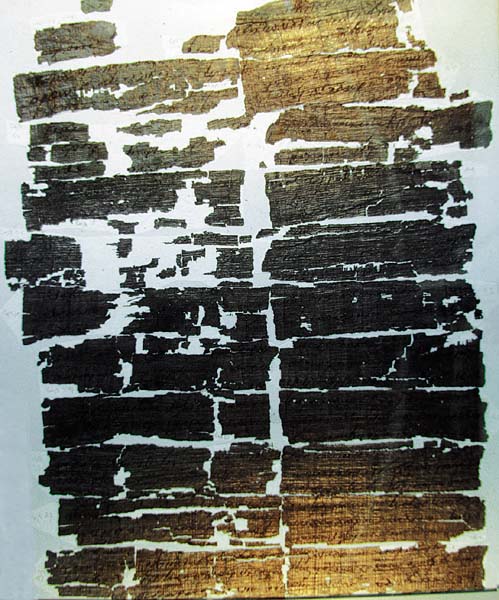

About 3 inches wide and tightly rolled, the papyrus scrolls had been completely carbonized by a fire that consumed the church, probably in the early seventh century. Even using the most sophisticated methods, the fragile, charcoal-like documents proved impossible to unroll; the conservators painstakingly peeled away each layer of papyrus in strips and attached each strip to special acid-free tissue paper. The conservation work was completed by a team of Finnish experts in May 1995.

Once the papyri were unwound and reassembled, the conservators photographed, digitized and deciphered the documents using special lighting techniques that helped distinguish the ancient black writing from the burnt, black surface of the scrolls. After more than five years of research, two teams of American and Finnish scholars—led respectively by Ludwig Koenen of the University of Michigan and myself—have deciphered most of the 152 papyrus scrolls.

Written between 537 and 592 A.D., these scrolls shed new light on one of the murkiest eras in Petra’s history. Until recently, almost nothing was known about Petra in the Byzantine period. Conventional wisdom held that the city entered a period of gradual economic and cultural decline after it was annexed by the Romans in the second century A.D. and was subsequently Christianized. A severe earthquake in 363 was thought to have destroyed a good deal of the city, and a second devastating quake was supposed to have led to its final abandonment in 551.

Most of the documents in our archive, however, date after the earthquake of 551—suggesting that Petra was by no means entirely abandoned. On the contrary, the documents paint a picture of a prosperous city with a vigorous, agriculturally based economy.

Written almost entirely in Greek (with a few lines in Latin), the texts found in the church are all economic and legal documents. They include contracts, wills, settlements of property disputes, and property registrations. Many of the records relate to one prominent local family, but the scrolls mention numerous people and places both within and outside of Petra. One of the scrolls has even helped us identify the church where the records were found; it refers to the building as the Church of St. Mary at Petra.

The key figure of the archive is a certain Theodoros, son of Obodianos, who served as the archdeacon of the Church of St. Mary and may also have been the bishop of Petra. Theodoros’s family originally came from the town of Kastron Zadakathon (modern Sadaqa), some 13 miles southeast of Petra, but Theodoros also seems to have owned land and administered property west of Petra in the Dead Sea Rift. One scroll, for example, was written at Gaza and reports on the archdeacon’s holdings in Eleutheropolis (modern Beit Jibrin, close to Jerusalem). Casual references to property near the Mediterranean coast make it clear that sixth-century Petra was not cut off from caravan and pilgrim routes, as many scholars previously maintained.

The texts also show a surprising persistence of Nabataean culture during the Byzantine period. Traditional Nabataean names continue to appear among the more common Greek, Roman and Christian names. For example, the 027name Obodianos is derived from the Nabataean king name Obodas; another name, Dusarios, retains the name of the Nabataean god Dushara (or Dusaras).

This suggests that even though Nabataean writing was no longer used after the fourth century A.D., the Nabataeans themselves did not disappear. Probably they adjusted to Roman rule, adopted Greek as their official language and converted to Christianity, while still maintaining certain elements of their culture, including traditional Nabataean names.

One of the scrolls, dating from 573, contains six copies of the last will and testament of another Obodianos, son of Obodianos. According to this document, Obodianos (junior) fell ill and promised all his belongings to two local charitable institutions. One was a church or monastery identified simply as the House of the Saint High Priest Aaron. (The biblical Aaron is traditionally thought to be buried near Petra.) The location of this house is not specified in the text (though we now believe we have identified the site), but its legal interests were represented by the presbyter of the monastery or church, Kyrikos, son of Petros. The other beneficiary was the Hospital of the Saint Martyr Kyrikos in Petra, represented by the archive’s key figure, Theodoros, who was probably the brother of the ill Obodianos.

This document (Scroll Number 6 in the register) is noteworthy for its very early references to both a monastery (if it really was a monastery) and a hospital. The Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai—generally regarded as the Near East’s oldest monastery—was known as a dwelling for monks as early as 300 A.D., but its central enclosed compound and outer fortifications were built by Emperor Justinian in 548 A.D., less than 30 years before this scroll was written. Similarly, the systematic building of hospitals in the region is not thought to have begun until sometime after the widespread famine of 536 and the great plague of 542. Did Byzantine Petra house one of Transjordan’s first important monasteries and one of its first hospitals?

Some of us who have been involved in conserving and deciphering the Petra scrolls are now trying to relate the texts to their topographical surroundings and the many unexamined archaeological remains in and around Petra. The Jabul Harun [Mount Aaron] Archaeological Project—a new Finnish excavation project led by Zbigniew Fiema and myself—has now identified a complex of buried buildings just below the summit of Mount Aaron that is almost certainly the House of St. High Priest Aaron monastery mentioned in Scroll Number 6. During our first season of fieldwork, we found a large church with mosaics and a chapel with “Aaron” inscribed on a marble orthostat found near its altar.

Around the sides of the mountain, we also uncovered an extensive riverbed and terrace irrigation system, complete with dams and cisterns. This may be the largest terraced irrigation system in southern Palestine from this period. These finds suggest that Mount Aaron was probably the site of a major Byzantine pilgrimage center. In future excavations, we hope to determine the exact relationship of this building complex to the nearby city of Petra.

We also plan to continue our papyrological studies of the scrolls themselves. The first volume of our translations is almost ready for publication, but the remaining decipherment and publication process will take at least another five years. Meanwhile, we still do not know why these papyri were deposited in a storage room adjacent to the church. Was this chamber actually part of some larger official building, such as the residence of a bishop? Are the Petra scrolls only one small part of a much larger archive or library? If so, maybe there are more carbonized books and records waiting to be found.