The Great Pergamum Asklepion

Sidebar to: Asklepios Appears in a Dream020

One of the largest and most active of Asklepios’s sanctuaries lay just outside the ancient city of Pergamum in northwestern Turkey. Dedicated to the god in the fourth century B.C., the sanctuary remained in use until at least the third century A.D., when Christian opposition to pagan forms of healing led to its decline.

Visitors to Pergamum’s Asklepion included the emperors Marcus Aurelius (161–180 A.D.) and Caracalla (211–217 A.D.). The best account of the sanctuary is by the orator Aelius Aristides (c. 117–181 A.D.), a notorious hypochondriac who at the age of 26 was struck by the first of a long series of maladies and then spent much of the rest of his life as a resident of the god’s sanctuary at Pergamum. His Sacred Tales records revelations made to him by Asklepios in multiple dream-encounters.

In the Roman period, Pergamum was the capital of the province of Asia. Its acropolis, shining like a marble gem on a steep ridge between two river valleys, strikes the eye for miles around even today. On the acropolis stood a library and temples in honor of the Olympian gods and deified Roman emperors. On a terrace just below the summit rested the Great Altar to Zeus, a massive U-shaped marble structure carved with images of the Olympian gods defeating their writhing foes in battle. (In the late 19th century, this altar was excavated and removed to Berlin, where it now stands reconstructed in the Pergamum Museum.)

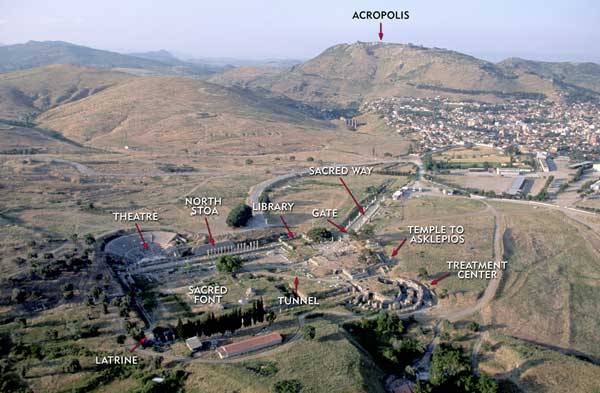

Asklepios’s sanctuary lies in the sprawling plain below the acropolis. An ancient visitor would have traveled a paved, covered road leading directly from the city walls to the sanctuary, about a third of a mile away. At the end of the road, a monumental gateway welcomed visitors into the vast sanctuary.

021

The layout of the sanctuary one sees today is the result of a large building initiative probably undertaken between 124 and 129 A.D., during the reign of the emperor Hadrian. A visitor of that time, like Aelius Aristides, would have looked out across a large open area framed by long porticoes to the north, west and south. These porticoes sheltered visitors from inclement weather, provided shady spots for socializing, and may have served as spaces for incubation (a process in which a patient is visited, and healed, by the god Asklepios in a dream). Near the west portico clustered older buildings, such as small temples to Asklepios and his relatives, rooms that may have been used for incubation, and wells (below, right). At the northwest corner stood a semicircular marble theater seating 3,500 spectators. Here plays and other events were performed at festivals in honor of Asklepios. At the southwest corner of the complex was a large latrine apparently divided into a men’s room (seating 40) and a women’s room (seating 20).

But the most lavish complex of buildings lay along the east end of the sanctuary, flanking the gateway. The northernmost of these buildings was a library, for Asklepios encouraged reading as a form of treatment. Just south of the library stood the monumental gateway, and south of the gateway was a round temple, dedicated to Zeus Asklepios (that is, Zeus in the guise of Asklepios), that was modeled on the Pantheon in Rome. The large southernmost building had at least two levels, with six smaller circular rooms attached to its perimeter. Excavators believe this was a treatment center. A 220-foot-long tunnel (still extant) led from this building to wells at the center of the sanctuary.

In antiquity, the sanctuary bustled with visitors, who came not only for healing but for performances in the theater, for processions, and to make offerings to the gods. The smell of sacrificial animals being burned wafted through the air, as did unpleasant body odors from people like Aelius Aristides—who, he informs us, was ordered by the gods not to bathe for five years. Vendors selling food and anatomical votives (offerings in the shape of a body part) peddled their wares from stalls just outside or even within the sanctuary. Small votives hung from the limbs of trees and the rafters of temples, while larger gifts, such as statues or sculpted plaques, stood on marble bases. At night, however, silence descended on the sanctuary, as those who incubated waited anxiously for sleep and the much-desired encounter with Asklepios.—B.W.