The Cave of Salome—Tomb of Jesus’s Disciple?

From the fifth to the eighth centuries, Byzantine Christians at Horvat Qasra in the Judean foothills venerated a centuries-old tomb they believed held the remains of a revered saint named Salome. They transformed the site’s well-appointed, multi-chambered Judean tomb complex into a small chapel, carving prayers addressed to “Holy” or “Lady” Salome, titles that implied her saintly status.

But who was St. Salome and why was she important enough to be venerated by early Christians? We’ll return to this question below, but first let us explore the archaeology of the original Jewish tomb complex and its later transformation into a Christian shrine.1

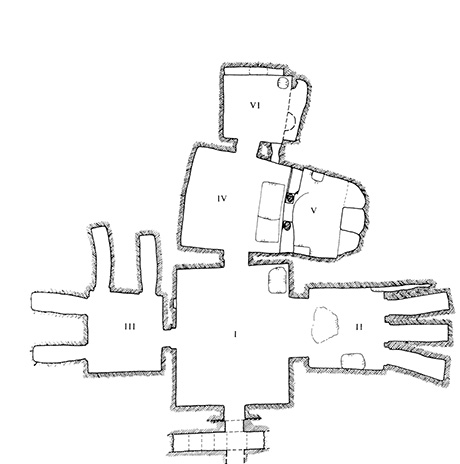

Located on a rocky hillside about 5 miles from Beth Guvrin, Horvat Qasra was originally a monumental underground burial complex of the early Roman period (first century BCE–second century CE). The tomb contained six main rooms, two of which (Rooms II and III) featured multiple kokhim, or elongated narrow niches for burials. Another room (IV) was used to store stone boxes (ossuaries) that held the bones of others previously buried in the tomb. Excavation of the tomb uncovered decorated ossuary fragments, oil lamps, and stoneware vessels, all typical of Judean tombs of the first and second centuries.

The tomb was entered through a sunken exterior courtyard dug out from the hillside that had a decorated façade, double colonnaded entry, and roofed vestibule. Stone fragments discovered during recent excavations hint that a Doric-style frieze surmounted the original façade. Similar Doric friezes decorated monumental early Roman tombs in Jerusalem, Samaria, and the Hebron hills.a The tomb’s opening was blocked with a large rolling stone, a frequent feature of wealthy Judean tombs.

After the mid-second century, the Horvat Qasra tomb was no longer used as a place for Jewish burial. Indeed, the site appears to have been largely forgotten until the fifth century, when Byzantine Christians converted the cavernous tomb complex into an underground chapel. Several of the tomb’s inner rooms were reworked for Christian worship, including Room V, where an altar was placed behind a pillared chancel screen, and Room VI, where an elongated niche (that likely held the chapel’s reliquary) was created as the focus of worship, indicated by years of lamp soot that covers the room’s blackened recesses. Interestingly, Rooms I, II, and III were not remodeled, and crosses carved on their walls indicate that their niches may have been reused for Christian burials. Yet this place was more than a chapel and burial ground.

Throughout the Holy Land, Byzantine Christians frequently identified ancient tombs as holding the remains of biblical figures. The biblical association of a specific place could come about through local stories and traditions, a revelatory experience, or inscriptions and skeletal remains found at the site. In the case of Horvat Qasra, it seems likely that early Christians identified the name “Salome” on one of the tomb’s earlier Jewish ossuaries (unfortunately now lost) and then venerated the bones it contained as the remains of an important biblical figure.

In any case, Horvat Qasra’s association with a woman named Salome is evidenced by its many Christian inscriptions written in Greek, Aramaic, and Arabic between the fifth and eighth centuries. Several directly address Salome for mercy and intercession: “Holy Salome, have mercy on Zacharias, son of Cyrillos,” and “Lady, have mercy on [Zacharias, son] of the brother Cyrillos.” The term “holy” was broadly used in the Byzantine period, and could apply to saints, angels, ascetics, clergy members, and anyone who lived an exceptional Christian life. However, the direct appeal to “Holy Salome” as “Lady” (kyria) implies she was a saint.

During the Byzantine period, then, this cave was clearly a martyrium chapel, dedicated to St. Salome. But who was she? We hear nothing about this chapel or its saint in our written sources from the time, nor does the site feature in any of the accounts of the many early Christian pilgrims who traveled to the Holy Land.

The scholars who first studied the tomb’s inscriptions believed Salome was most likely a woman known not from the Bible but rather from an apocryphal late second-century work, the Protevangelium of James.2 This curious tale gives an expanded version of Jesus’s birth, including an episode involving a midwife named Salome, who does not actually deliver the baby Jesus but rather arrives on the scene soon after his birth. Salome doubts Mary’s virginity so decides to examine her, and when she does, her hand is struck with pain and shrivels up. Horrified, she appeals to God. An angel tells her to touch the baby Jesus and she will be cured. The miracle happens, and she praises God. She is thus the first of many people to be healed by Jesus. But such people are not usually esteemed as saints (see sidebar).

There were, of course, other Salomes. There was the girl who danced for Herod Antipas, in the story of the death of John the Baptist. Though only referred to as the daughter of Herodias in the Gospels (Mark 6:14–29; Matthew 14:1–12), she was identified as Salome in Josephus (Antiquities 18.137). However, she was never a saint; quite the opposite.

Then there was the Salome who was a companion to the holy family in Egypt. She appears in a sixth-century work known as the History of Joseph the Carpenter and in other works of the same time preserved in Coptic and Arabic. She may well be a midwife but, in this case, a believing one, as we find in the Arabic Infancy Gospel, also from the sixth century. Yet again, however, she would not have been considered a saint.

Finally, in the Gospel of Mark, Salome was one of the women who dutifully came to the tomb where Jesus was laid, with perfumed oil, in order to complete the burial rituals for the dead (Mark 16:1–2). Salome is listed as of one of Jesus’s many women disciples who followed and served him in Galilee, came with him to Jerusalem, and stayed to witness his crucifixion (Mark 15:40–41).

Salome the disciple and “myrrh-bearer” was widely remembered and is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church. She was also held to be the mother of James and John, the sons of Zebedee (see Matthew 20:20; 27:56). However, in the earliest literature, she is usually a solitary and independent figure, and in one apocryphal gospel (Gospel of the Egyptians), she affirms to Jesus that she has done well not to bear children. She and Mary Magdalene appear together as Jesus’s foremost women disciples in both mainstream and heterodox Christian literature of the second to fourth centuries (e.g., Gospel of Thomas, First Apocalypse of James, Secret Gospel of Mark).3 In an orthodox Syrian work titled Testament of Our Lord (1:16), from the early fourth century, Salome appears with other women disciples asking questions of Jesus after he is raised. In the influential Apostolic Constitutions (3.1–13), another fourth-century Syrian work, she is listed among the women “with us” (i.e., the apostles), a group that includes “the Mother of our Lord and his sisters.”

In fact, in some early Christian traditions, Salome was remembered as one of Jesus’s two sisters, the other of whom was named Mary. This is attested by the fourth-century scholar Epiphanius, who names them as Joseph’s daughters by his first wife (Panarion 78.8.1, 9.6; Anacoratus 60.1). In refuting a sect who worshiped Mary the mother and also had women as leaders, Epiphanius says, “God did not agree to this being done with Salome, or with Mary herself” (Panarion 79.7.3), which implies there was a Salome who was held in high esteem, as either a disciple, sister, or both. In comparing Salome with Mary the mother of Jesus, Epiphanius simply cannot be referring to the midwife, but rather someone who was important and highly regarded, just like Mary.

Furthermore, a tenth-century monk from Mar Saba in the Judean Desert records that on April 25 there was the feast day of the “holy mothers”: Mary the Mother of God, Mary Magdalene, Mary of Jacob, Salome, Joanna, and Martha and Mary, the sisters of Lazarus.4 This was certainly holy Salome, not the doubting midwife.

It seems, then, that the Horvat Qasra chapel most likely commemorated the burial place of Salome, disciple, myrrh-bearer, and perhaps even sister of Jesus. Does the site’s archaeology tell us anything else about her or the Byzantine Christians who believed she was buried there?

Horvat Qasra’s cave complex is part of a much larger hilltop site that extends across 7.5 acres and overlooks nearby valleys and agricultural fields. Perched on top is a large and wealthy fortified residence, most likely built in the early to mid-first century BCE. The residence features a central building (measuring c. 65 by 65 ft) with living areas and storage rooms built around a central courtyard. The residence, which was protected by a well-built tower on the north and on all sides by a massive sloping revetment wall, was the center of a large agricultural estate. Various features were carved into the hill’s soft limestone, including quarries, cisterns, and columbaria (dovecotes), the latter likely used to produce both fertilizer and meat. The estate also featured several underground rooms and installations (including a possible ritual immersion pool, or mikveh) that were later connected by tunnels and used as hideouts during the Bar-Kokhba Revolt (132–136 CE).

The original Salome was likely one of the residents of this wealthy estate who, following her death, was buried in style in the monumental family tomb carved into the hillside below. Beyond this, the site’s archaeology tells us little about who this Salome was or whether she had any relationship to Jesus, his family, or his teachings.

As for those early Christians who commemorated her burial centuries later, there is significantly more to say. Excavations of the tomb’s exterior courtyard have revealed what appears to be a small monastery, measuring just 75 by 50 feet, built outside the tomb’s entrance. It was divided into two parts: an area in the north similar in size to the tomb vestibule, and a larger area to the south, bounded by edges cut into the hillside. A wall with six decorated pilasters gave access to the area in front of the cave chapel. The southern area had a central courtyard surrounded by monastic cells and a thick southern wall with a single entrance.

Such rural monasteries were often established around a memorial church or shrine that commemorated a well-known figure or event from the Bible. They could be small or large and had different layouts, but the small ones were usually square, two-story structures built around a central courtyard. They were largely occupied by monks who, over the centuries, welcomed visitors who wished to visit their shrine. Like many such buildings, the Horvat Qasra monastery had a cistern for storing water as well as a cruciform font used for baptism. It is possible that further excavation in the vicinity will reveal pottery kilns, olive presses, and other features typically associated with the day-to-day functioning of such monasteries.

Many beautifully decorated oil lamps dating to the eighth century were also recovered from the monastery. These, along with the early Arabic inscriptions found in the chapel, indicate that Christian veneration of the site continued well into the early Islamic period. Shortly thereafter, however, the monastery and cave chapel fell into ruin, likely destroyed by one of several earthquakes that devastated the region in the eighth century.

Unfortunately, we likely will never know the true identity of the first-century Jewish woman whose name and remains were commemorated at Horvat Qasra. She could possibly have been Salome, the disciple of Jesus, but it’s also possible she was another Salome who, like many wealthy Jewish women of her day, was buried in a monumental cave tomb on the grounds of her family estate. But whoever this Salome was, archaeology shows she certainly had a remarkable afterlife.

Deep beneath the hilltop site of Horvat Qasra in the Judean foothills is a fifth-century cave chapel dedicated to St. Salome. Originally the ancestral tomb of a first-century Jewish family that owned a large agricultural estate on the hill above, the cave complex was repurposed by early Christians as a shrine to the revered saint. But who was St. Salome, and does her shrine commemorate the burial place of one of Jesus’s first disciples?

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1. For Jerusalem, see Andrew Lawler, “Who Built the Tomb of the Kings?” BAR, Winter 2021.

Endnotes

1. For details, see Amos Kloner, “The Cave Chapel of Horvat Qasra,” ‘Atiqot 10 (1990), pp. 129–137 (Hebrew), 29*–30*; and Amos Kloner, Boaz Zissu, and Nili Graicer, “The Hiding Complexes at Horvat Qasra, Southern Judean Foothills,” in A. Tavger, Z. Amar, and M. Billig, eds., In the Highland’s Depth: Ephraim Range and Binyamin Research Studies, vol. 5 (Ariel-Talmon: Bar-Ilan University, 2015), pp. 151–163 (Hebrew).

2. Leah Di Segni and Joseph Patrich, “The Greek Inscriptions in the Cave Chapel at Horvat Qasra,” ‘Atiqot 10 (1990), pp. 141–154 (Hebrew), 31*–35*.

3. Helen Bond and Joan Taylor, Women Remembered: Jesus’ Female Disciples (London: Hodder, 2022), pp. 42–43.

4. Nikoloz Aleksidze, “Calendar of Ioane Zosime,” Cult of Saints in Late Antiquity database, E03720 (http://csla.history.ox.ac.uk/record.php?recid=E03720).