Who Built the Tomb of the Kings?

030

On a cool and clear fall morning in 1863, a French senator and explorer made an astounding discovery. Within a hidden chamber lit by torches deep within Jerusalem’s largest tomb, Félicien de Saulcy pried opened the lid of an ancient sarcophagus to reveal “a well-preserved skeleton, the head resting on a cushion.” But when his assistant slid his hands under the skull, disturbing the fragile fragments, the figure “vanished in the blink of an eye as if by magic.” 1

All that was left was a patch of brown soil and splinters of bone, along with thousands of bits of twisted gold thread. De Saulcy was disappointed that the grave, part of what had long been known as the Tomb of the Kings, contained no treasure. “Not a piece of jewelry, not a ring, not a necklace,” he wrote bitterly. “Nothing, absolutely nothing.”

But he did find an inscription on the side of the sarcophagus that he took for ancient Hebrew. On his return to Paris, he deposited the sarcophagus and its contents in the Louvre, translated the writing, and declared that he had found the remains of the wife of Zedekiah, the last Judean king before the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E.

His claim caused an international sensation, since it made the sarcophagus the first important relic directly related to the Old Testament. Visitors flocked to the museum to see the exhibit, and interest in the find sparked subsequent British, German, and Russian excavations in Jerusalem.

De Saulcy was soon forced to revise his theory, however. Upon further examination, the 031 inscription turned out to be in Aramaic, a language that only became common in Jerusalem after the Babylonian destruction. In addition, the tomb clearly was built in the Roman style of the first century C.E. The Frenchman conceded, as other scholars and explorers had begun to argue, that the grave was more likely the resting place of a much later queen, Helena of Adiabene, whose son Izates ruled over a small kingdom in what is today northern Iraq.

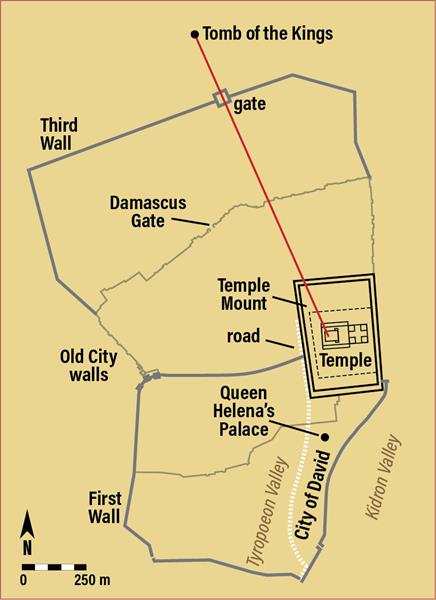

The only contemporary mention of Helena comes from the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, who wrote that Helena, a convert to Judaism, relocated to Jerusalem probably between 30 and 50 C.E. to “worship at the Temple of God” (Antiquities 20.49). The pious expat reportedly built a grand palace, perhaps in the area between the Temple Mount and the City of David,a fed Jerusalem’s poor during a famine, and then returned home at the death of Izates (Antiquities 20.51–53).

According to Josephus, Helena died soon after her return to Adiabene, and her bones, along 032 with those of Izates, were sent to Jerusalem for burial “that they should be buried at the pyramids which their mother had erected; they were three in number, and distant no more than three furlongs from the city” (Antiquities 20.95).

Elsewhere, Josephus notes that the grand tomb was located along the city’s Third Wall (War 5.147), a fortification begun during the mid-first century C.E. to accommodate Jerusalem’s growth to the north and west. Scholars have long argued over the precise location of this wall.b In 2016, Israeli excavators claimed to find evidence for one section that lies northwest of today’s Old City. The presumed line of the fortification likely continued several hundred yards to the east of the recent dig, passing close to the Tomb of the Kings.

Since de Saulcy’s day, few have questioned that the Frenchman found the complex built by Helena to house her remains and those of her family. Citing new archaeological and epigraphic clues, however, French scholar and Dominican monk Jean-Baptiste Humbert of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française in Jerusalem now argues that even though the tomb was eventually used by Helena and her descendants, 033 it was originally meant to be the final resting place for another royal: Herod Agrippa I (r. 41–44 C.E.), the grandson of Herod the Great and the last of his line to rule over Judea.2

As a youth, Herod Agrippa was sent by his famous grandfather to be raised in the court of Rome, and the young prince became a favorite of Emperor Tiberius. He made powerful friends, including two future emperors, Caligula and Claudius.

When Claudius assumed control of the empire after Caligula’s assassination in 41 C.E., he appointed Agrippa to replace the Roman prefects who had ruled Judea for decades, including the notorious Pontius Pilate, who took office in 26 C.E. While Pilate is remembered for sentencing Jesus to death, Herod Agrippa is recalled as the man responsible for the death of the apostle James (son of Zebedee) and the arrest of the apostle Peter (Acts 12:1-3). According to Acts 12:21-23, the king was hailed as a god during a public address and was struck down by an avenging angel.

Whatever the cause, his sudden death in 44 C.E. made him the final Judean monarch—his son, Herod Agrippa II, controlled only territories outside Judea—and his final burial site has long been a mystery. Theories abound. A few years ago, Israeli archaeologist Gabriel Barkay of Bar-Ilan University argued that the ruler’s body was placed in the so-called Tomb of Absalom (see Strata: Caring for the Dead in Ancient Israel), located just east of the Temple Mount, but he admits the evidence for this is circumstantial.

Even if Herod Agrippa’s body ended up in the Tomb of Absalom, there’s good reason to believe the Tomb of the Kings was originally meant for him and only subsequently used by Queen Helena and her descendants.

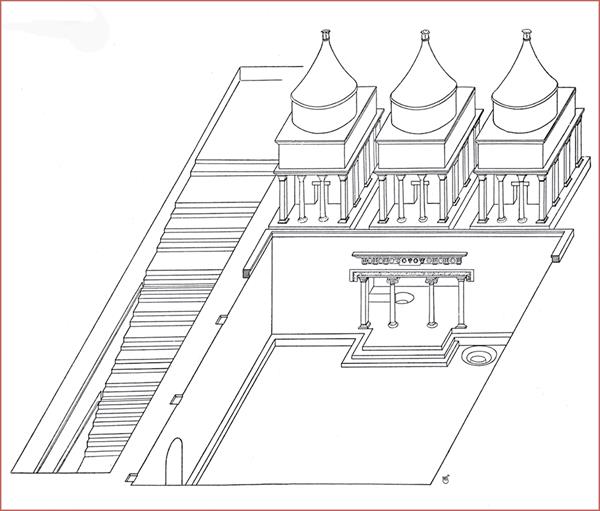

Jean-Baptiste Humbert has devoted decades to studying the Tomb of the Kings, which is 034 located just down the street from the École Biblique, where he has lived and worked for more than half a century, and a ten-minute stroll north of Jerusalem’s Damascus Gate. Its original entrance was obliterated when the road beside it was widened in 1937. Visitors today pass through an iron gate and descend a monumental staircase that leads to a pair of large ritual baths hewn out of the rock. Then they pass through a gate into a vast sunken courtyard big enough to contain two tennis courts.

On the west side of the plaza, an enormous carved lintel, once held up by two massive Ionic columns, overhangs the entrance. The second-century C.E. Greek traveler Pausanias was dazzled by the tomb’s grandeur and claimed that an ingenuous device automatically rolled back a stone that sealed the entrance on one day of the year: “Then the mechanism, unaided, opens the door, which, after a short interval, shuts itself” (Description of Greece 8.16.3–22.1). A huge mill-like stone remains beside the sole entry.

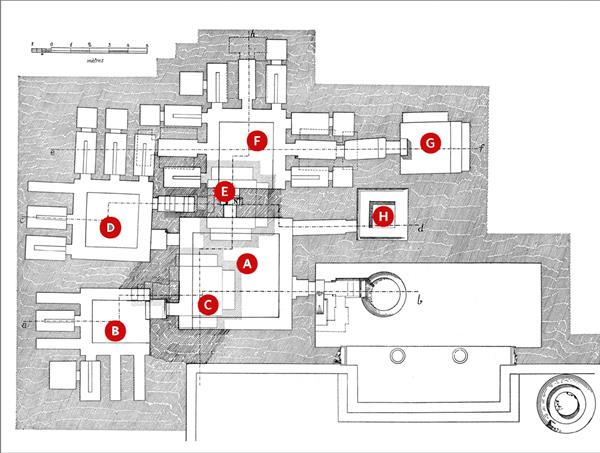

Inside lies a remarkable labyrinth with smaller rooms radiating off several main chambers, capable of holding 40 to 50 burials. The inscribed sarcophagus found by de Saulcy was located in one of the deepest of these rooms, sealed off from the other niches. Part of the box had been shaved off to fit it through the tight space leading into the chamber. In all, five sarcophagi were found in the tomb: Two are now in the Louvre in Paris, while the other three are scattered throughout Jerusalem’s Old City.c

035

Since its discovery in 1863, the tomb has continued to attract visitors and, more recently, ultra-Orthodox Jews who sought to pray here (see sidebar), but it has rarely been the subject of additional investigation or research. In 2010, however, when the complex was closed for structural repairs and renovation, Humbert, together with his colleague Jean-Sylvain Caillou, then of the Institut français du Proche-Orient (French Institute for the Near East), took the opportunity to conduct the first detailed modern survey of the site.

During the survey, new details emerged about the tomb’s construction, design, and architectural features that suggest the story of its creation and subsequent reuse is far more complex than originally thought. Humbert believes that the complex, with its enormous sunken plaza, first served as a quarry for the city’s Third Wall, a massive undertaking begun, according to Josephus, by Herod Agrippa (War 5.148). This expansive rock-cut clearing was then adapted and transformed to serve as a suitable resting place for Herod Agrippa and his heirs.

What is more, it is possible that the tomb was carefully aligned with the Jerusalem Temple, which the Judean king’s famous grandfather renovated as part of his effort to create one of the largest religious compounds in the Roman Empire. It was built on the same axis as some theoretical reconstructions of Herod’s central sanctuary. Herod Agrippa’s desire to build a lasting monument for himself and his successors would have been influenced by Herod the Great and also by his time in Rome, where emperors had begun to adorn a crowded and ramshackle 036 city with marble temples, baths, and grandiose graves.

His untimely death in 44 C.E., however, likely meant that work on his planned monumental tomb complex had to be halted, and his remains were ultimately deposited elsewhere in Jerusalem. Humbert believes the findings from his survey show that Herod Agrippa’s planned tomb was, in fact, never fully completed. He noticed, for example, that a significant amount of the tomb’s exterior detail remained unfinished. Blocks by the baths—two huge cisterns at the base of the tomb’s monumental stairs—were cut but not detached, and the courtyard was not fully smoothed. In addition, the interior of the tomb was strangely bare, suggesting that the tomb construction was abandoned.

But such an extensive and, presumably, empty mausoleum might have appealed to another wealthy royal looking for her own grand mausoleum. “Herod Agrippa had no time to finish the tomb—he ruled for only three years,” Humbert said. “Helena died around 56 C.E., so she could have bought the unfinished tomb.”

Jewish law forbade selling or transferring an existing tomb to non-family members. But, like any real estate, tombs or chambers within tombs that had not been used could be purchased.3 Burial sites also were commonly reused over time. Within the Tomb of the Kings, de Saulcy encountered the cremated remains of urns containing what he believed were Roman soldiers buried after 70 C.E. Later archaeologists found figurines of Roman deities at the site, another sign of its non-Jewish reuse.

The theory that Helena purchased and expanded the tomb is supported by new evidence for the three previously unidentified “pyramids” that Josephus mentions in association with Helena’s tomb. The use of such a design is not a surprise, since pyramid-shaped mortuaries were fashionable across the empire in the early Roman era, from the Pyramid of Cestius on Rome’s outskirts to the conical roof of Jerusalem’s Tomb of Absalom. According 037 to Josephus, even the now-lost tomb of the Maccabees—the kings of Judea before the Romans arrived—was topped with seven pyramids (Antiquities 13.211).

When Humbert and Caillou cleared soil and debris from the top of the broad lintel that towers over the tomb’s courtyard, they noted square notches cut above the north end of the lintel that measured about 16 by 16 feet. Humbert argues that this was the foundation of one of the pyramids, and that the lintel’s length left room for two more of identical size, though the foundations for these have since worn away. The three pyramids, arranged side by side, would have made an impressive sight for those standing in the courtyard and also allowed the tomb to be visible from the city walls.

It is possible that these pyramids served more than a decorative function; they could have been the repository for Helena’s bones or her ashes brought from northern Iraq. Jewish law required burial beneath the ground and forbade cremation, but placing remains in towers was a widespread practice in other parts of the Roman Near East. Whether Helena and her family—some of whom may not have converted to Judaism—adhered to Jewish tradition for their interment is unclear.

Wherever Helena was buried, Humbert doubts that she was the person in the sarcophagus retrieved by de Saulcy. Instead, the fragile bones were more likely those of one of Helena’s royal descendants. If Helena and her son Izates died in Adiabene, then their remains hardly would have arrived in Jerusalem after such a long journey as intact skeletons. It would have been far more likely that their bones were transported in stone boxes called ossuaries that were widely used in first-century C.E. Judea. That would preclude Helena as the person laid to rest in the sarcophagus.

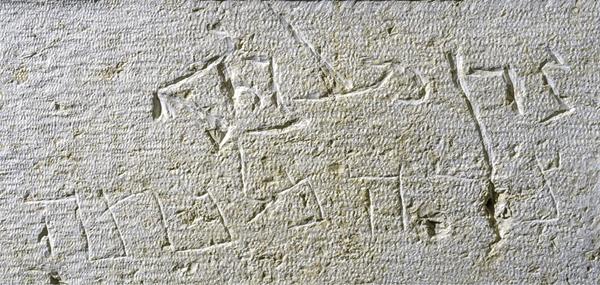

Further, new readings of the inscription on the sarcophagus support Humbert’s theory. The two-line inscription, comprising only four words, was carved into the box’s side. The upper line, written in Syriac Aramaic, reads ṣdn mlkt’, and the lower line reads ṣdh mlkth. The first word in each line is a personal name (Tsadan and Tsadah) while the second means queen.

The inscription has long posed a challenge to epigraphers. “It’s fascinating,” said Michael Langlois, a philologist and religion professor with the University of Strasbourg. “It uses two variants of Aramaic: Syriac and Judean.” The use of Syriac Aramaic, the dialect in northern Iraq in that day, points to a connection with Adiabene.

The origin of the personal names has long been disputed. Some researchers posit that both are variations of the phrase “our mistress.” Others argue the one on top derives from an ancient Assyrian root that means “supplier of food”—a hint that this was the queen who fed Jerusalem in a famine. Another theory is that 038 the word is a variant on the name Sarah, a Jewish moniker that Helena may have adopted after her conversion. Although scholars have long tried to link the enigmatic name to Helena, there is no direct evidence to support this view.

A recent detailed analysis of the sarcophagus’s inscription by Alain Desreumaux, an epigrapher at the French National Center for Scientific Research, concluded that the first line may actually date to the end of the second century or start of the third century C.E., long after the death of Helena. If his analysis proves correct, then the buried queen might indeed have hailed from Adiabene, but she would have lived much later than the one mentioned by Josephus.

Finally, Humbert also points out that the inscription appears to have been quickly and imprecisely carved. That, plus the fact that the sarcophagus is remarkably plain and was not designed to fit in its chamber, seems at odds with the luxurious and careful construction of the complex.

Humbert believes that the weight of this new evidence points to Herod Agrippa as the tomb’s originator, with Helena purchasing and adding to the tomb for her descendants—one of whom may have included the vanishing skeleton encountered by de Saulcy. Humbert has yet to spell out his theory in scholarly detail, and other academics are split on whether his approach has merit. But if his argument holds up, then Jerusalem’s most lavish tomb—and the site that began the archaeological mania to dig in and around the Holy City—was designed for the last Judean king but used by a foreign queen.

Since its discovery, most scholars have argued that Jerusalem’s Tomb of the Kings belonged to Queen Helena of Adiabene. But was she the original commissioner of the tomb? Our author presents new archaeological clues that suggest the ownership history of this impressive monument is far more complex than originally thought.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1. For the possible discovery of Helena’s palace, see R. Steven Notley and Jeffrey P. García, “Queen Helena’s Jerusalem Palace—In a Parking Lot?” BAR, May/June 2014.

2. Hershel Shanks, “The Jerusalem Wall That Shouldn’t Be There,” BAR, May/June 1987.

3. See “Sarcophagi from the “Tomb’ of the Kings,’ ” sidebar to “Queen Helen’s Jerusalem Palace—In a Parking Lot?” BAR, May/June 2014.