Endnotes

Much scholarly analysis and debate followed these discoveries. See Paul V.C. Baur et al., The Excavations at Dura-Europos, Preliminary Reports (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ., 1929–1952); Carl Kraeling, The Excavations at Dura Europos, Final Reports, vol. 8, pt. 1, The Synagogue (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ., 1956; reprinted Hoboken: KTAV, 1979); Kraeling, The Excavations at Dura-Europos, Final Reports, vol. 8, pt. 2, The Christian Building (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ., 1967), which included an earlier bibliography; a projected final report volume on paintings at Dura has been abandoned. See also, e.g., Marie-Henriette Gates, “Dura-Europos: A Fortress of Syro-Mesopotamian Art,” Biblical Archaeologist 47 (1984), pp. 166–181; Joseph Gutmann, The Dura-Europos Synagogue: A Re-evaluation (1932–1992), rev. ed. (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992); Susan Matheson, Dura-Europos: The Ancient City and the Yale Collection (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ., 1982); Ann Perkins, The Art of Dura-Europos (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973); Michael I. Rostovzeff, Dura-Europos and Its Art (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1943); L. Michael White, Domus Ecclesiae—Domus Dei: Adaptation and Development in the Setting for Early Christian Assembly (Yale University dissertation, 1982); Hershel Shanks, “Dura-Europos: Window into a Vanished Jewish World,” in Judaism in Stone: The Archaeology of Ancient Synagogues (New York: Harper & Row/Washington: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1979), pp. 78–96; Annabel Jane Wharton, “Good and Bad Images from Dura Europos: Texts, Contexts, Pretexts, Subtexts, Intertexts,” Art History 17 (1994), pp. 1–25.

For reports on the continued work at Dura, led by French and Syrian archaeologists, see Syria 63 (1986), 65 (1988) and 69 (1992).

George D. Kilpatrick, “Dura-Europos: The Parchments and the Papyri,” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 5 (1964), pp. 215–225.

Gutmann, “Early Synagogue and Jewish Catacomb Art and Its Relation to Christian Art,” Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 21:1 (1984), pp. 1313–1342.

Elias Bickerman, “Symbolism in the Dura Synagogue—A Review Article,” Harvard Theological Review 58 (1965), pp. 127–151, here p. 145.

See Marcel Simon, “Remarques sur les synagogues à images de Doura et de Palestine,” Recherches d’histoire Judéo-Chretienne (Paris: Mouton, 1962), pp. 188–198, 204–208; and Herbert Kessler, “A Response to Christianity?” in Kurt Weitzmann and Kessler, The Frescoes of the Dura Synagogue and Christian Art (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 1990), pp. 178–183.

William L. Petersen, Tatian’s Diatessaron: Its Creation, Dissemination, Significance, and History in Scholarship (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994).

A few scholars have argued for the presence of Jewish-Christians at Dura, but none of their arguments is persuasive. See Ignazio Mancini, Archeological Discoveries Relative to the Judaeo-Christians: Historical Survey, Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Col. Min. 10 (Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 1970), pp. 138–147, who makes claims concerning chi-rho monograms, but see also Richard Frye et al., “Inscriptions from Dura-Europos,” Yale Classical Studies 14 (1955), pp. 127–201. And see Theodor Klauser, Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum (JAC) 10 (1976), pp. 105–106. Jacob L. Teicher, for example, claims that the only Hebrew manuscript found at Dura is a Jewish-Christian document (in “Ancient Eucharistic Prayers in Hebrew [Dura-Europos Parchment D. Pg. 25],” Jewish Quarterly Review 54 [1963–64], pp. 99–109.) But when one recalls that Teicher also insisted that Qumran manuscripts (Dead Sea Scrolls) were Jewish-Christian documents as well, it will be no surprise that his theory has persuaded few. Another article attempted to show, with dubious evidence, that one artist worked on the paintings of both church and synagogue. (See Robert du Mesnil de Buisson, “L’inscription de la niche centrale de la synagogue de Doura-Europos,” Syria 40 [1963], pp. 303–314.) He claims that two inscriptions in the two buildings refer to the same man (supposedly named Sisa or Siseos), but, even if true, this does not demonstrate that the individual was a Jewish-Christian artist. The artists who worked on the paintings need not necessarily have been either Jewish or Christian; they may have been hired contractors who were neither.

For discussion of varieties of ancient Jewish-Christianity and for evidence that the issue was of concern to rabbis, see Stephen Goranson, The Joseph of Tiberias Episode in Epiphanius: Studies in Jewish and Christian Relations (Duke University dissertation, 1990), pp. 73–97. Also note that the Babylonian Talmud disapproves of the

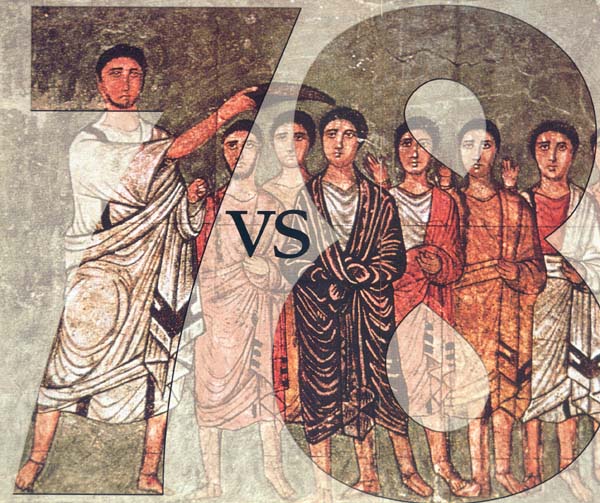

First Chronicles 2:13–15 lists only seven sons in a genealogy, as does the first-century C.E. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, but if the artist was relying on these sources, he must have had some reason for rejecting the narrative account in Samuel. The great scholar of Jewish legends Louis Ginzberg “was puzzled the Dura artists should have painted six brothers [plus David], as he felt it unlikely that they would have resorted to the Chronicles or to Josephus’ account” (as reported by Joseph Gutmann, “The Illustrated Midrash in the Dura Synagogue Paintings: A New Dimension for the Study of Judaism,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 50 (1983) pp. 91–104, here p. 97.). Evidently, the artist chose, or was told by those who commissioned the artwork, to draw a total of seven—not eight—brothers.

Rachel Wischnitzer, “Number Symbolism in Dura Synagogue Paintings,” in Joshua Finkel Festschrift, eds. Sidney Hoenig and Leon Stitskin (New York: Yeshiva University Press, 1974), pp. 159–171.

See David Ulansey, “Solving the Mithraic Mysteries,” BAR 20:05; and Roger Beck, Planetary Gods and Planetary Orders in the Mystery of Mithras (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1988).

See Raymond E. Brown, The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Graves—A Commentary on the Passsion Narratives in the Four Gospels, 2 vols. (New York: Doubleday, 1994), appendix 2, “Dating the Crucifixion (Day, Month, Date, Year), pp. 1350–1378.

For an example of an illustration of this verse, see the third- or fourth-century sarcophagus from Trier with eight figures in the ark; Reinhart Staats, “Ogdoas als ein Symbol für die Auferstehung,” Vigiliae Christianae 26 (1972), pp. 29–52, fig. 2. Another early Christian sarcophagus from Pisa depicts, on the right, eight women mourning the deceased, with a Good Shepherd figure and twelve sheep on the left (Josef Wilpert, I sarcofagi Cristiani antichi (Rome: Pontifico Instituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1929), vol. 1, pl. 83, no. 3. Klauser proposed (in JAC 8 [1965], note 101a) that the eight women plus the deceased on the Pisa sarcophagus represent the nine muses, but this is unlikely since none of the identifying accoutrements of the muses appear.

See Franz J. Dölger, “Zur Symbolik des altchristlichen Taufhauses, I. Das Oktogon und die Symbolik der Achtzahl,” Antike und Christentum 4 (Münster: Aschendorf, 1934), pp. 153–187; Antonio Quacquarelli, L’ogdoade patristica e suoi riflessi nella liturgia e nei monumenti, Quaderni di Vetera Christianorum 7 (Bari: Adriatica, 1973).

Then, as part of a litany, Thomas, who anointed the king with oil and baptized him, said, “come, mother of seven houses, whose rest was in the eighth house.” Translation from section 2 of the Syriac version by William Wright, Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles (London: Williams and Norgate, 1871), p. 166.

See Edward C. Whitaker, Documents of the Baptismal Liturgy (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1970); Willy Rordorf, Sunday: The History of the Day of Rest and Worship in the Christian Church (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1968); Jacob Vellian, ed., Studies on Syrian Baptismal Rites, Syrian Church Series 6 (Kottayam, India: C.M.S. Press, 1973); Josef A. Jungmann, The Early Liturgy: To the Time of Gregory the Great (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1959).

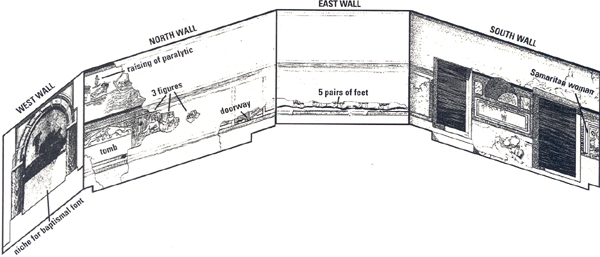

Because the drawings of the men and the beds are quite different, Kraeling’s suggestion of a “before-and-after” scene is not persuasive (The Christian Building, pp. 59–60).

André Grabar, Christian Iconography: A Study of Its Origins, Bollingen Series 35:10 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ., 1968), p. 124.

Carl Kraeling’s generally excellent final report on the Christian building and other publications have made major contributions to our understanding of this painting. Nonetheless, his overall interpretation of this scene is not persuasive. He argued that this painting included “before and after” scenes, even though it is difficult to imagine why. He proposed that two additional figures formerly appeared inside the tomb. However, after a complicated and tenuous argument, in which he looks to the Arabic translation of Diatessaron, searching for additional women, or “Marys,” at the tomb, Kraeling admits that five “Marys” inside the tomb would appear to be “crowded…into too narrow a space.” (Kraeling, The Christian Building, p. 85). In the three surviving ends of the groups of figures in the tomb, the artist left ample space before and after the group of women; it is most reasonable to assume the same generous space was left on the broken portion of the wall. The reconstruction of Henry Pearson, the excavation’s architect, shows a total of eight figures. (See Baur et al., The Excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Reports 5 [New Haven, CT: Yale Univ., 1934], pl. 41.) According to yet another participant, the excavation director, Clark Hopkins, “First on the north wall is shown the tomb with the three Marys behind, followed by five other women, around the corner of the north wall.” (Clark Hopkins, Discovery of Dura Europos [New Haven, CT: Yale Univ., 1979], p. 114.)

Kenan T. Erim, “Récentes découvertes à Aphrodisias en Carie, 1979–1980,” Revue archéologique (1982), p. 167, fig. 12; and Aphrodisias: City of Venus Aphrodite (New York: Facts on File, 1986), p. 122 (with a color photograph). Note that texts of the gnostic baptizing Mandaeans refer to a personified Sunday figure.

See Weitzmann and Kessler, The Cotton Genesis: British Library Codex Cotton Otho B. VI, The Illustrations in the Manuscripts of the Septuagint 1 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1986).

Otto Demus, The Mosaics of San Marco in Venice, (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1984); Johan J. Tikkanen, Die Genesismosaiken von S. Marco in Venedig und ihr Verhaltniss zu den Miniaturen der Cottonbibel, Acta Societatis Scientiarum Fennicae 17, (Helsinki, 1889; reprinted Soest: Davaco, 1972).

Franz Landsberger. “The Origin of the Winged Angel in Jewish Art,” Hebrew Union College Annual 20 (1947), pp. 227–254; Marie Thérèse D’Alverny, “Les anges et les jours,” Cahiers archéologiques 9 (1957), pp. 271–300. See Weitzmann and Kessler, The Cotton Genesis, 40, for differing depiction of angels in the Cotton Genesis. In 1 Enoch 61:1, according to Ephraim Isaac, the version with no wings is older than the one with wings; in James Charlesworth, ed., The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1983), vol. 1, p. 7.

The potential for confusion appears in a statement from Clement of Alexandria’s Stromata 6.16: “For one may venture to say that the eighth is properly the seventh, and the seventh actually the sixth; that is the eighth is properly a sabbath, and the seventh a day of work.” See Everett Ferguson, “Was Barnabas a Chiliast? An Example of Hellenistic Number Symbolism in Barnabas and Clement of Alexandria,” in Greeks, Romans, and Christians, Abraham J. Malherbe Festschrift, (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1990), pp. 157–167, here p. 166.

Excerpta ex Theodoto 63, as recorded by Clement of Alexandria. Several gnostic texts found at Nag Hammadi also emphasize the ogdoad (as the eighth day or eighth heaven); see, for example, Gospel of the Egyptians 41, 58; Paraphrase of Shem 46; Testimony of Truth 55; Zostrianos 6; Origin of the World 102–104; Apocalypse of Paul 23–24. These texts are translated in James Robinson, ed., The Nag Hammadi Library in English (New York: Harper & Row, 1977, and later editions).