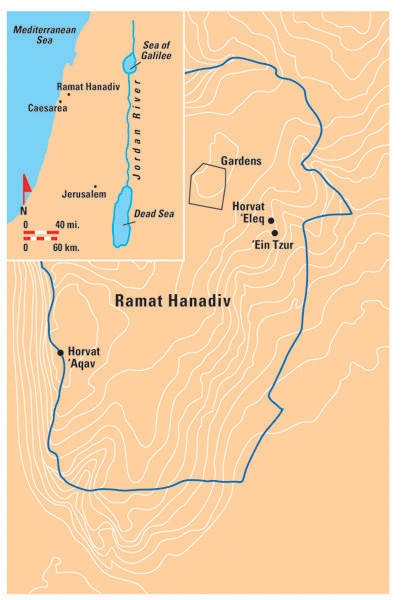

On a ridge about 3 miles east of Caesarea, deep in the Carmel range, Baron Edmond de Rothschild is buried alongside his wife Adelaide. The Baron was a key 19th-century Zionist whose support enabled a number of nascent Jewish settlements to survive. He provided these early pioneers with land, homes, agricultural equipment and education in agronomy. Wishing to remain anonymous, however, he was widely referred to simply as Ha-Nadiv Ha-Yadua, the Well-Known Benefactor or simply Ha-Nadiv, the Benefactor. Rothschild died in Paris in 1934, but in 1954 his remains were reinterred at their present location, now known as Ramat Hanadiv—the Heights of the Benefactor. From Ramat Hanadiv to the west, a beautiful vista spreads out toward the coastal plain and the Mediterranean Sea. To the east the fertile valley (the Valley of Hanadiv) is bordered by the northern edge of the Samaria Hills.

The foundation that Rothschild left supported the recent excavations at Ramat Hanadiv, which I led. And it is not entirely inappropriate that the excavations revealed one of the most magnificent country villas in Israel—indeed in this part of the world.

Who lived here? Probably one of the wealthy, well-connected Jewish families known in the New Testament as Herodians.

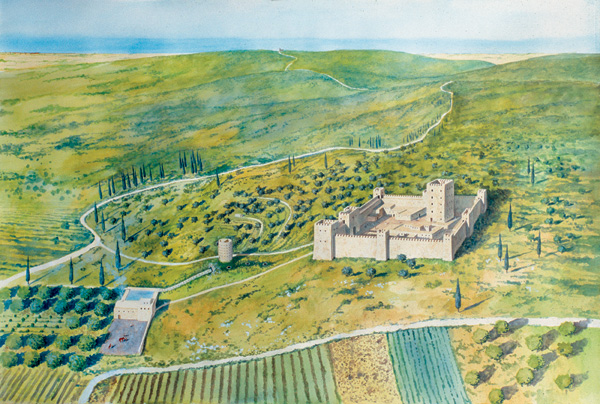

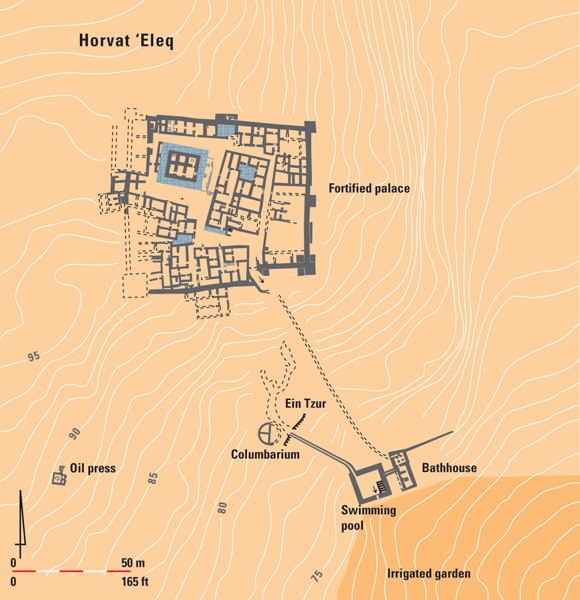

The Carmel ridge that comprises Ramat Hanadiv actually includes two ancient sites, one on the eastern slope and the other on the western slope. In between are the beautifully lanscaped Ramat Hanadiv Gardens, the burial site of the Baron. Horvat ‘Eleq (its Hebrew name; in Arabic it is called Khirbet Umm el ‘Eleq, a colorful name that means “the ruin of the mother of leeches”), perched on the eastern slope, is the larger, no doubt because of its proximity to the only spring in the area. Horvat ‘Eleq covers about 7.5 acres and was occupied in the Hellenistic (fourth-second century B.C.E.), Roman (first century B.C.E.-second century C.E.) and Turkish periods (19th-early 20th century C.E.). Its most impressive remains, however, date from the end of the time of Herod (37–4 B.C.E.) until the Great Revolt of the Jews against Rome (66–70 C.E.).

Much smaller is Horvat ‘Aqav, on the western ridge. Finds here were almost exclusively from the early Roman and Byzantine periods (first century B.C.E.-sixth century C.E.).

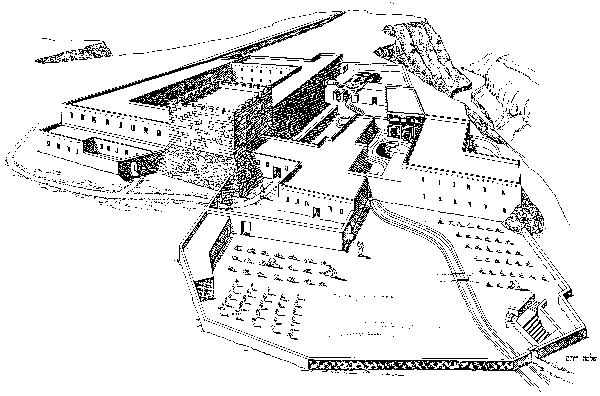

We spent 15 years excavating Horvat ‘Eleq.1 Indeed, it took us several years before we knew what we were excavating. At first, we thought the site was a fort because of the thickness of the walls—more than 6 feet. The pottery clearly established its date—that of King Herod. Gradually, the layout of the building emerged from the ruins. When we found a tower in each of the four corners of the building, we realized that this is what Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, meant by a “fortified palace.” It even has a special name in Greek, a tetrapyrgion, which means a “four-towered palace.”2

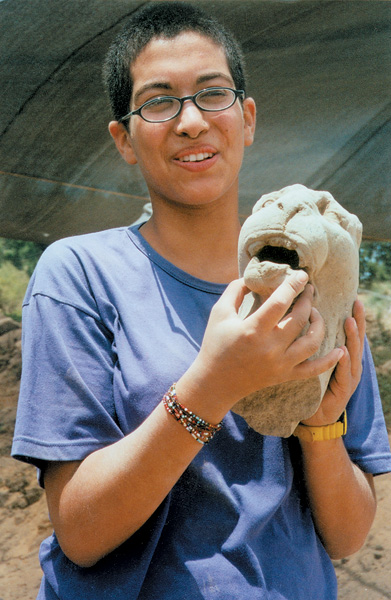

The dig had more than its share of surprises. On one morning that I shall never forget, the still cool air of an industrious morning dig was broken by a shriek. It was the voice of Miriam Samet, the counselor of our group of Israeli teen volunteers. Everyone rushed to where the kids were digging. There, embedded in the debris of animal bones and pottery shone the white, marble head of a panther, its mouth open in a mute roar. What was it doing here? In the Herodian period, Jews strictly prohibited the reproduction of humans and animals. At only one other Jewish site has anything like this been found. At Herodium archaeologist Ehud Netzer uncovered a head of Silenus, the god of wine, in a Herodian bathhouse.3 None of the other major Jewish sites—Jerusalem, Masada, Gamla—had anything like it. Could we be sure our site was Jewish?

Certain other factors might at first lead us to wonder. For example, the orientation of the walls of the building is on a precise north-south axis, which follows a well-known Roman custom. The symmetrical layout of the walls reflects meticulous planning, which is also evident in the grid pattern of the passages between various components in the complex.

We are nevertheless confident that the lord of this elegant Roman-style manor house was Jewish. After all, Herod ruled a Jewish kingdom. Rome did not impose direct rule on Judea, as it was then known, until 6 A.D.; it did so as a result of the inept rule of Herod’s son Archelaus. Even then, the Romans did not touch private property (except, ironically, that of the king, which was transferred to the direct ownership of the fiscus, the Roman treasury). Everything else they left to the local rulers, who continued to enrich themselves through the proceeds from their vast holdings.

There are other indications that this country manor was inhabited by Jews. We found quantities of high-quality stoneware in the house that, according to a study by archaeologist David Amit, was probably manufactured in Jerusalem. It bears the same characteristics as the stoneware found in the Burnt House and Herodian Mansions in Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter.a Stoneware, expensive though it may have been, was not subject to ritual impurities, like clay vessels that had to be destroyed once they had become defiled. The appearance of stone vessels in abundance, as at Horvat ‘Eleq, is generally considered an ethnic marker—the sign of a Jewish site.b

This quality of stoneware is reflected in the story of wedding at Cana where “six stone jars were standing there, for the Jewish rites of purification” (John 2:6). That the wine was in stone jars assured that it was made by Jews and would not impart impurity.

Another ethnic marker found in our excavations was the lack of pig bones. A scant 1 percent of the animal bones we excavated were identified as pig bones. Perhaps these were the remains of meals consumed by non-Jewish servants.

What about a miqveh, the Jewish ritual bath found at Jewish settlements? We did excavate a miqveh at the other Herodian site on Ramat Hanadiv, Horvat ‘Aqav, on the western slope. The two sites were closely connected by an ancient road to one another. But more significant is the fact that a miqveh was not needed at Horvat ‘Eleq because that site was adjacent to the only spring on the ridge, Ein Tzur. A Jewish ritual bath must consist of “living water,” water that comes directly from the sky, not water from a cistern, for example. The water of a spring or a lake qualifies. (Just as miqva’ot were not needed at Horvat ‘Eleq, so were they not needed at a place such as Capernaum, on the Sea of Galilee.) By contrast, the people living at Horvat ‘Aqav, who were further from the spring, had to build a miqveh into which rainwater would flow.

Amazingly, the palatial complex at Horvat ‘Eleq contained at least 150 rooms. It was the local Jewish version of the grand Roman villa. Within the complex was a powerful tower that stood, not in the center of the complex, but close to its northwestern corner. Apparently the builders wanted to place it at the highest point on the natural hill. From here it controlled the main gate to the complex, which we presume was in the western facade. Originally, the tower rose four or five stories, a veritable skyscraper in its day.

Around the tower was a massive wall called a proteichisma (Greek for “forewall”). A flight of steps 10 feet wide led up from the proteichisma to the tower. South of the steps, opposite the entrance to the tower, was a cistern, which stored rainwater that drained into it from the roof of the tower and the surface of the proteichisma. The cistern provided an independent water source for the tower, although its main water source was probably Ein Tzur.

At the bottom of the cistern we found quantities of broken pottery, the latest of which dated to the first century C.E., indicating that the site was abandoned thereafter, probably during the Great Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 C.E.).

Within the tower we found a plastered bathtub and some beautiful oil lamps, suggesting that, while the tower was not primarily a dwelling, there may have been a kind of “penthouse” at the top that the landlord reserved for special occasions.

The main living quarters were on the southern side of the complex. Some of the walls, made of finely cut ashlars (squared blocks of stone), have been preserved to a height of as much as 7 feet. The evidence indicates this area was especially elegant. In the debris of a staircase that led to what was once a second floor we found remains of beautiful green, red and white marble panels that once covered the floors in a style known as opus sectile. There is no marble in Israel; it all had to be imported. Only during the second and third centuries C.E., as the economy expanded, do we find marble commonly used in Israel. The marble pavement at Horvat ‘Eleq is among the earliest ever found in Palestine, a sign that the family that lived here wanted only the best of everything, no matter the cost.

Another rare find was stone grillwork from a window. The only known parallel comes from Herod’s palace at Herodium.4 Two beautifully carved Ionic capitals indicate that columns no doubt added to the splendor of the facade.

While the entire complex had about 150 rooms, the living quarters alone consisted of about 50 rooms and chambers of various sizes.

Between the living quarters and the spring was a garden where family and friends could gather. Adjacent to the spring was a bathhouse with a hypocaust system of sub-surface heating that served as a furnace kept stoked with boiling water to create steam. In the first century B.C.E., this was a new technology. The water was fed from the nearby spring, Ein Tzur, by a tunnel 170 feet long. A sluice gate at the mouth of the tunnel, when closed, required a cave to be dug that filled with water. This created a pool where bathers could have a relaxing float. Another spring-fed pool was located outside and served as a swimming pool as well as irrigation source for the nearby garden where exotic plants were cultivated. A garden like this was known, aptly, as a paradisos.

The well-fortified tower not only provided security, it stood as a symbol of prestige and beauty. From the top of the tower the lord of the manor could keep an eye on all of his agricultural lands (as much as 2,500 acres) as well as the main road leading southwestward to Caesarea, the region’s largest city, its main port and one of Herod’s grandest building projects.

The complex at Horvat ‘Eleq has no parallels in Israel, although there are similar sites in Greece and the Aegean islands. Certain components of our site, however, can be seen at other sites in Israel. The tower and proteichisma, for example, are found at Qumran by the Dead Sea (very near where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered; see box), at Qasr e-Leja in western Samaria, and at several sites in the Hebron hills as well as in the valleys of Arad and Beer-Sheva. Similar storerooms are found at Masada and Gamla, and dining rooms at Qumran and Hilqiyah’s palace on the western slopes of the Hebron hills. Similar marble has been found at Jericho, Masada and Machaerus in Jordan. All of these sites, like Ramat Hanadiv, were isolated centers of royal estates.5 The complex is so grand that we may imagine one of Herod’s sons, perhaps Archealaus or Antipas, living here as lord of the manor.

The gentlemen farmers who lived in these elegant manor houses in the first century B.C.E. and the first century C.E. had good reason to be concerned for their security, however. There was no middle class at this time, only the rich (who were usually landowners) and the peasants. While the latter were not always poor, those who were day laborers, like migrant farmers today, lived from hand to mouth. By the first century C.E., this clearly polarized class system was deteriorating rapidly.

These social tensions are vividly reflected in the famous parable of the vineyard (Mark 12:1–11). As at Horvat ‘Eleq, the Biblical vineyard is protected by a tower. When the absent landlord sends a succession of servants to collect the rent in kind, the first is beaten, the second beaten and insulted, and the third killed. Finally, the landlord sends his beloved son. On his arrival the “tenants said to one another, ‘This is the heir; come let us kill him, and the inheritance will be ours.’” They seized and killed him too, and threw his body out of the vineyard.

The term “Herodians” appears three times in the New Testament (Matthew 22:16 and Mark 3:6 and 12:13) and refers to subjects of the king who, in exchange for their loyalty, enjoyed various economic rewards. Wealthy landowners who had become established in the days of the Hasmonean Jewish rulers who preceded Herod in the first century B.C.E. continued to expand their estates by deception and oppression, inciting mass resentment.6 Social polarity was exacerbated, leading to unrest. The number of bandits also increased. Fortified manor houses such as Horvat ‘Eleq reflect this lack of internal security. Unlike Roman villas, which were open to the landscape, in Judea they were closed, heavily defended complexes.

Herod continued the social and economic traditions of his Hasmonean predecessors. He was at the top of a pyramid that included his sons, among them Archaelaus, Antipas and Philip, various and sundry relatives from his home country of Idumea (in the Hebron hills), as well as army veterans who had served him faithfully. On this fortunate group, known as “friends of the king,” Herod bestowed large parcels of land—which he confiscated from his enemies—in and around Jericho, at Ein-Gedi on the shore of the Dead Sea, in Heshbon in Transjordan and Sebastia in Samaria.

These homes were not even the permanent residence of their owners but simply their country estates. Gospel accounts indicate that the landlord did not occupy the premises continuously. One of Mark’s parables is an example. Jesus tells his listeners: “‘Heaven and earth shall pass away; but my word shall not pass away’” (Mark 13:31). Then he tells them: “Beware, keep alert; for you do not know when the time will come. It is like a man going on a journey, when he leaves home and puts his servants in charge, each with his work, and commands the gatekeeper to be on the watch. Therefore, keep awake—for you do not know when the master of the house will come, in the evening or at midnight, or at cockcrow, or at dawn, lest he may find you asleep when he comes suddenly” (Mark 13:32–36).

In describing another landlord who comes and goes, Matthew 24:45 speaks of “the faithful and wise servant, whom his master has put in charge of his household, to give to them their allowance of food at the proper time. Blessed is that servant whom his master will find at work when he arrives.” The faithful servant is contrasted with the wicked servant who takes advantage of his master’s absence to abuse those under his authority.

An archaeological clue at Horvat ‘Eleq that the permanent home of this family was elsewhere is the absence of a family tomb in the vicinity of the house and grounds, in the style of the cave-tomb of the wealthy Joseph of Arimathea in which Jesus was laid, according to the Gospels.

These powerful men imitated the Roman way of life in Judea. Luke describes such a rich man “dressed in purple and fine linen … who feasted sumptuously every day” (Luke 16:19). When the rich man died, Luke goes on to tell us, he suffered the eternal torments of hell.

Other aspects of the extravagant life at Horvat ‘Eleq are reflected in the small finds. A small gold clamp once pinned the corner of a toga to the shoulder. An unusually tiny spindle whorl must have been used in the manufacture of embroidery thread.

A gold teardrop earring probably once sparkled in the ear of the landowner’s wife. Small balls of brilliant blue cobalt were used as eye shadow and also as a dye. (As opposed to the rest of our finds, however, we will probably never be sure whether this cobalt came from the Herodian household or perhaps rolled down into the site on the heels of a mouse scurrying its way from the layer of Turkish ruins above it.)

A carnelian signet ring carved with the image of Poseidon (or perhaps Apollo) in beautiful detail may have belonged to the lord of the manor.7

The elegant dishes that graced the table of this house are known as Western terra sigillata (“stamped clay” in Latin). They have a gleaming, rust-colored hue. Among them we found one that bore the imprint of Gellius, a well-known first-century Italian pottery maker. Curious guests had no need to turn over their dish unobtrusively to take a peek at its make—Gellius left his mark, a footprint, right inside the bowl for all to see, along with the word Gelli (“of Gellius” in Latin), as can be seen in the photo.

The oil lamps found at Horvat ‘Eleq were both rare and common. A mold-made lamp in fine Roman Imperial style was intricately decorated in a kind of “Roman Baroque,” with a protruding spout and a ring handle. On the other hand, simple Herodian-style oil lamps were wheel-made with spouts glued on.

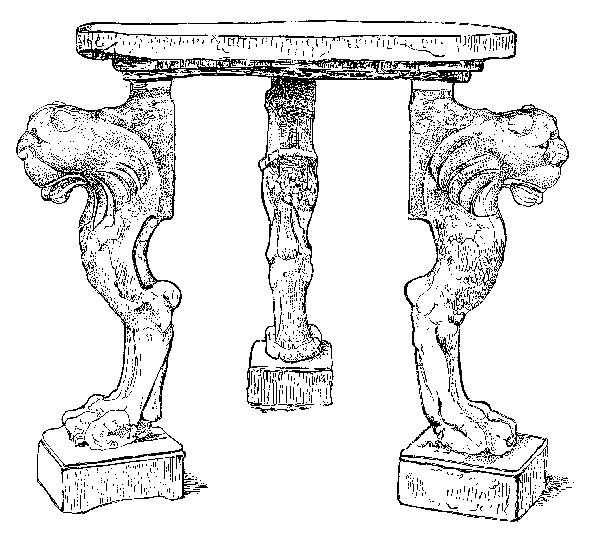

Finally, we return to the startling panther head discovered by Miriam Samet. It turned out to be part of a leg of a large elegant table. Geological analysis pinpointed the origin of the marble of which it was carved: the quarries of Thasos in Greece.8 The half-ton table probably made its way from one of the Greek centers, such as Corinth, or perhaps even from Italy to the port in Caesarea. From there it would have been trundled by cart to Horvat ‘Eleq, where it graced a small interior garden of the family who lived in the complex that we now know so intimately. We know this table stood in the small courtyard garden because of the especially dark, rich soil in which it was found. This type of garden, known as a viridarium, was an indispensable component of the pleasures enjoyed by country villa owners of the time.

Uncredited photos courtesy of the author; field photos by Zev Radovan.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Nitza Rosovsky, “A Thousand Years of History in Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter,” BAR May/June 1992.

See Yitzhak Magen, “Ancient Israel’s Stone Age: Purity in Second Temple Times,” BAR, September/October 1998.

Endnotes

For the final report of the remains until 1998, see Yizhar Hirschfeld, Ramat Hanadiv Excavations (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2000).

Ehud Netzer, Hasmonean and Herodian Palaces at Jericho (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2001), p. 114.

For more references, see my article, “Early Roman Manor Houses in Judea and the Site of Khirbet Qumran, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 57 (1998), pp. 161–189.

See Martin Goodman’s book, The Ruling Class of Judaea (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1987), and James H. Charlesworth, Jesus Within Judaism (New York: Doubleday, 1988).

For more information about the signet ring, see Orit Peleg, “Roman Intaglio Gemstones from Aelia Capitolina,” in Palestine Exploration Quarterly 135, no. 1 (2003), pp. 52–67.