Bethsaida Rediscovered

Long-lost city found north of Galilee shore

044

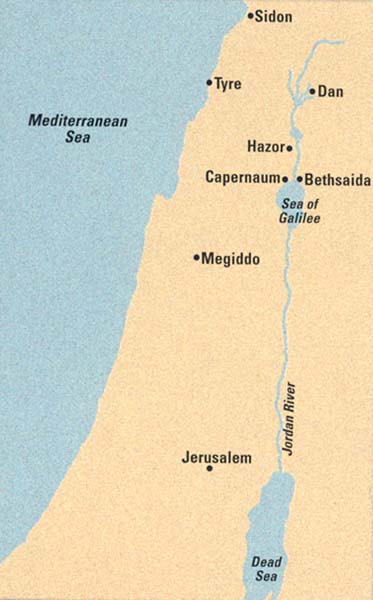

Bethsaida is the town that disappeared. Soon after playing a prominent role in the Gospels—Bethsaida is mentioned more often in the New Testament than any city except Jerusalem and Capernaum—this fishing village on the Sea of Galilee simply became lost to history. Early Christian pilgrims went in search of it, but they had no idea where to find it.

Even in modern times, three different sites north of the Galilee have been proposed as ancient Bethsaida. Happily, however, we can report that Bethsaida has been found once again. And not only have we rediscovered the village of Jesus’ time, but we are uncovering a rich history going back to the age of King David.

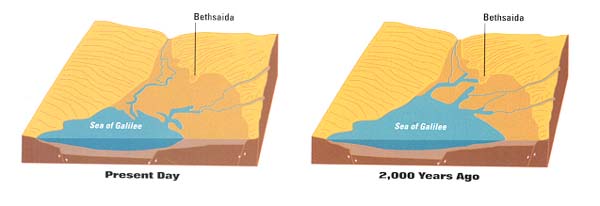

The key to our identification of ancient Bethsaida was the realization that the site lies not on the Galilee shore but one and a half miles north of it. How can a fishing village sit so far from the water? The answer to that riddle is an important part of our story. But we are getting ahead of ourselves …

In the tenth century B.C.E., Bethsaida was at the heart of the small kingdom of Geshur. History’s first mention of Geshur is as a city-state; it appears in the el-Amarna letters, an archive of cuneiform tablets found at Tell el-Amarna, Egypt, that consists of diplomatic correspondence between two pharaohs—Akhenaten (also known as Amenophis IV, 1352–1338 B.C.E.) and his 046father Amenophis III (1390–1352 B.C.E.)—and the rulers of small states in Palestine and elsewhere that were under Egyptian hegemony.

Tenth-century B.C.E. Bethsaida allied itself with King David and his dynasty (as a result, Bethsaida absorbed many Israelite cultural influences). Our excavations have been uncovering an impressive city going back to that time, leading us to believe that Bethsaida was the capital of Geshur. In the ninth century B.C.E., Geshur was annexed by the kingdom of Aram-Damascus; a century later it would be swallowed up by the mighty Assyrian Empire.

The Bible reflects the military strength of the Geshurites: “The Israelites failed to dispossess the Geshurites and Maacathites, and Geshur and Maacah dwell among the Israelites to this day” (Joshua 13:13).

The Bible mentions two Geshurite kings by name: Amihud (or Ami-Hur) and his son Talmai (2 Samuel 13:37). King David married Talmai’s daughter Maachah (2 Samuel 3:3), presumably to cement relations between the two kingdoms. The usual practice was for the daughter of the more powerful ruler to marry the weaker ruler. If that held true in this case, then Geshur was the stronger kingdom.

In royal marriages, a queen did not simply move to her new home; a royal retinue of courtiers, architects and masons would come along to build and staff her palace. Maachah would have brought to Hebron (David’s first royal seat) and then to Jerusalem the architectural traditions of Geshur and, more generally, of Aram-Damascus.

Maachah was the mother of Absalom, the son of David who murdered his half-brother Amnon. Absalom then fled to Geshur, his mother’s birthplace (2 Samuel 13). Following a three-year exile, Absalom returned to Jerusalem and fomented an ill-fated revolt against his father, which ended with his death at the hands of Joab, David’s loyal general (2 Samuel 14–18).

Absalom left behind a daughter named, like her grandmother, Maachah. The younger Maachah went on to marry her cousin Rehoboam, Solomon’s son, who ruled Judah after the monarchy split into the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. The Bible says that Rehoboam loved Maachah “more than 047all his wives and concubines” (2 Chronicles 11:21). But was it pure romance? The Bible also tells us that “there was a war between Jeroboam [the ruler of the northern kingdom of Israel] and Rehoboam all their life long” (1 Kings 15:6). Maachah was far more than the object of Rehoboam’s affections—she provided Judah with an important link to the powerful Aramean kingdom to the north.

In the New Testament, Bethsaida plays an even more prominent role, with some of the key events in Jesus’ Galilean ministry taking place in or near Bethsaida. The Gospel of Luke places the feeding of the five thousand at Bethsaida (Luke 9:12–17). And according to the Gospel of Mark, Jesus cured a blind man at Bethsaida (Mark 8:22–25). Mark also locates one of Jesus’ most famous miracles—his walk on the water—near Bethsaida (Mark 6:45–51).

The Gospel of John records that Bethsaida was the home of the disciples Philip, Andrew and Peter (John 1:44). But Bethsaida was also the target of a withering curse by Jesus: “Then he began to reproach the cities in which most of his deeds of power had been done, because they did not repent. ‘Woe to you, Chorazin! Woe to you, Bethsaida! For if the deeds of power done in you had been done in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented long ago in sackcloth and ashes’”(Matthew 11:20–23).

From a historian’s viewpoint, Bethsaida was indeed cursed—it disappeared for 17 centuries. When the intrepid American minister Edward Robinson explored the Holy Land in 1838, he had nothing to guide him along the Sea of Galilee other than a compass. On the northern shore, he clambered atop the largest mound he could see—a nameless rise called simply et-Tell (the Mound), located about one and a half miles from the shore—and suggested that it may have been Bethsaida. Half a century later, the German scholar Gottlieb Schumacher raised the key problem with that identification: How could a site so far from the water be home to the New Testament fishing village? He suggested instead that two ruins nearer the shore, el-Araj and Mesadiyye, were better candidates.

To make matters even more perplexing, et-Tell sits east of the Jordan River, placing it in the Golan region; 048the Gospel of John, however, says Bethsaida was in the Galilee (John 12:21), which is west of the Jordan. In an attempt to resolve the problem, Bargil Pixner, a historian of early Christianity (and a BAR author), has suggested that the Jordan River changed its course over time; therefore, Bethsaida could have been located on the Golan shores of the lake during one period and on the Galilee shores in another.

That confused state is where matters stood when we began our excavations at et-Tell in 1987.1 Two of us (Arav and Freund) were principal investigators, but we were fortunate to have available to us the geological expertise of Jack Shroder, today a coinvestigator on the excavation and coauthor of this article. We approached him with the “Bethsaida dilemma”: We suspected et-Tell was the site of the ancient city, but it seemed too far from the water. It only took one look at the geological maps of the region for Jack to formulate the hypothesis that would eventually solve the riddle: Today’s shoreline is not necessarily the ancient shoreline. First, et-Tell sits on one of the world’s most active fault lines,2 and the shorelines of bodies of water near fault lines are always changing. Second, lake levels change over time, and their shorelines shift, usually downward from where they receive their water (the Galilee is fed from the north by the Jordan River and discharges into the Jordan on the south). Third, rivers, including the northern branch of the Jordan, build up deltas: They carry silt downstream and deposit it at the mouth of the river (the Mississippi Delta is the great example in America). As a result, ancient port cities typically lie farther inland today than they did in antiquity.

Geological investigation has proven Jack’s initial hypothesis right: Up against the base of the et-Tell mound, we found lake clays containing crustacean microorganisms. At one time, Bethsaida was right on the water! Further work has refined that finding. At the base of the tell lie terraced deposits of gravel and boulders on top of the lake clays. Carbon 14 dating of bovine bones and other organic matter underneath the boulders has yielded a date between 68 and 375 C.E. We believe that a cataclysmic event, probably the major earthquake of 363 C.E., swept a vast amount of basalt boulders, rock, gravel, soil and artifacts across the plain on which et-Tell lies, cutting Bethsaida off from the shore.3

Our 13 years of research have also shown that of the various candidates for Bethsaida, only et-Tell was occupied around the time of Jesus, in the Hellenistic (332–37 B.C.E.) and early Roman (37 B.C.E.–324 C.E.) periods. This past season we conducted a ground-penetrating radara survey of the alternative site of el-Araj. Beneath the Byzantine (324–638 C.E.) level lies nothing more than beach sand.4 Mesadiyye, for its part, contains Byzantine remains only. Edward Robinson’s hunch 160 years ago was right, after all: Et-Tell is ancient Bethsaida.

It is not surprising, then, that when Byzantine Christian pilgrims went searching for Bethsaida, they scattered small shrines and relics at various points along the shore. They simply did not know where the city had been.

049

Bethsaida was founded in the tenth century B.C.E., atop a small basalt outcrop that descended to the lake. A very short and steep ravine ran east of the outcrop, while the lake straddled its south and west sides; the easiest way to reach the city was from the north. Like many other cities in the Iron Age, Bethsaida was built in two stages, with an upper city built first on the 050northeast side of the mound and a later, lower city at the foot of the western side of the hill.

The upper city contained mostly public structures: the city wall and fortifications, a monumental city gate, a palace and perhaps a temple. We know the upper city existed at least by the tenth century B.C.E. because at the foot of a tower that overlooked the lower city we uncovered pottery dating to that time. This is the earliest pottery uncovered at the site. We have not yet reached Bethsaida’s earliest levels, however. We have a ninth-century B.C.E. gate, but we suspect that a tenth-century B.C.E. gate lies below it and that the city wall may date to Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.) or perhaps even earlier.

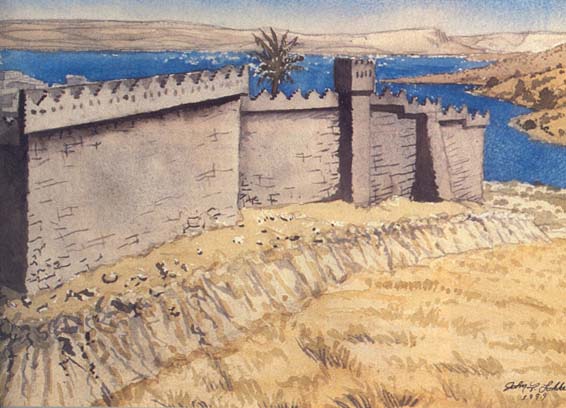

The massive fortifications we have uncovered so far were designed to counter the most feared military weapon of the time: the Assyrian battering ram. These defenses consisted of a short but steep glacis (a sharply angled man-made slope) encasing a rampart built with crushed limestone and dirt. At the top of the rampart stood an impregnable wall about 20 to 25 feet thick and preserved to a height of 5 feet, filled with fieldstones and outside layers of large boulders. Similar contemporaneous fortification systems have been found at other major cities in the region, including Dan, Hazor and Megiddo. But the width of Bethsaida’s walls and their excellent state of preservation are unparalleled.

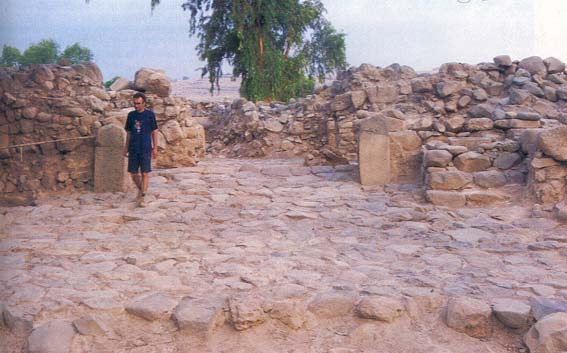

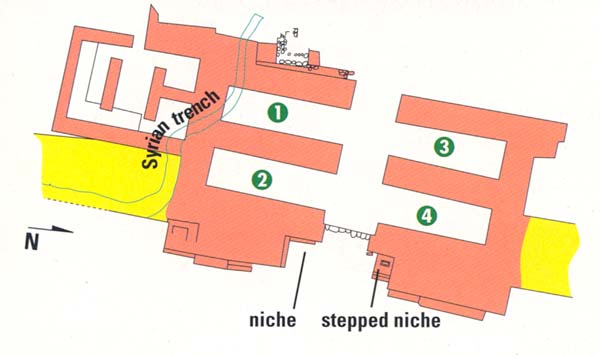

The most impressive structure we have found so far is the ninth-century B.C.E. city gate. To our complete surprise, it is located on the east side of the tell, facing the steep ravine, on top of a man-made rampart. As previously mentioned, the easiest access to Bethsaida is from the north; for ten years it never occurred to us that the high heap of stones and dirt on the east side could be hiding the city gate. After we began excavating in this area, we realized that the heap was the result of the destruction wrought in the late eighth century B.C.E. by the Assyrian ruler Tiglath-pileser III.

As at several important cities, Bethsaida’s impressive gateway was actually made up of two gates—an outer gateway and an inner gateway. At the outer gate, measuring 26 by 32 feet, we found one tower; a second tower almost surely flanked the entryway. Once inside this outer entrance to Bethsaida, visitors faced a 100-foot-long plaza paved with large basalt flagstones, with small stones filling the gaps.

At the far end of the plaza stood the inner gate, consisting of two towers, each 20 by 32 feet, with four large chambers—two on each side—behind them. The largest and best-preserved four-chambered gate ever found 051in Israel, it measures 57 by 115 feet and is preserved today to a height of 10 feet. It was built of partly dressed (smoothed) basalt stones, plastered in red and covered with whitewash. Its upper stories, of which there may originally have been two or three, were built of large sun-dried bricks that were also plastered and completely covered with whitewash.

The dominant color of the gateway was white. None of the black basalt core was visible on the outside. A low bench ran in front of the towers, where the city elders may have gathered to hold court.

In one corner of each tower of the inner gateway (see plan) was a niche, apparently for a cultic installation. Similar niches have been discovered at Megiddo, Dan and Carchemish. When we first detected the niche in the northern tower, we knew we had found something rare and unexpected. Two 1-foot-high steps led into the area, which measures 7 feet deep, 4 feet high and 5 feet wide and, like the rest of the gate, was built of plastered and whitewashed basalt stones. Near the niche we discovered a basalt stele depicting a bull-headed guardian figure with long crescent-shaped horns wielding a dagger. We believe this bull represents one of Bethsaida’s chief deities. Unfortunately, the stele was no longer intact; we found it in five scattered pieces. As we were clearing the area, we recalled the passage in Lamentations 4:1 in which the prophet bemoans the destruction of Jerusalem: “The sacred stones are scattered at the head of every courtyard.” We suspect that the stele was deliberately destroyed during the Assyrian attack on Bethsaida.

Only three figures are known to resemble the one on our stele. Two were found in south Hauran, in southern Syria, and one comes from Gaziantep, in southern Turkey. The two from Hauran feature a sun disk between the bull’s horns.

Othmar Keel, a leading specialist in Near Eastern iconography, believes the bull-headed figure represents the moon god and notes that Mesopotamian religious texts sometimes refer to the moon god Sin as a bull.5

Moon god worship was one of the leading religious cults in ancient Mesopotamia, where two areas were particularly famous for it: Ur, in southeastern Mesopotamia, and Haran (not to be confused with Hauran), in southern Turkey. Interestingly, in the Bible both centers are associated with Abraham (see “Abraham’s Ur: Is the Pope Going to the Wrong Place?” and “Abraham’s Ur: Did Woolley Excavate the Wrong Place?” in this issue). Worshipers of the moon god were particularly intrigued by the question of creation, especially in what order things came to be. In their view, darkness was the primordial state of the universe; the moon god, as lord of the darkness, was the primary deity and the creator of the universe.

The stele at Bethsaida is the southernmost appearance in Syro-Palestine of a representation of the moon god. The association of Abraham with centers of moon god worship may indicate the influence of this tradition on early Israelite religion, with Bethsaida possibly serving as the conduit of this cult into Israel.

Underneath the largest intact piece of the bull stele was a smooth basalt basin; the stele sealed the basin’s contents like a time capsule. Apparently the stele once stood behind the basin, inside the niche. The basin contained two perforated cups, each with three short legs, which served as incense burners. These incense burners, which are known from other sites, date to the second half of the eighth century B.C.E. This confirmed our hunch that the gate was destroyed by Tiglath-pileser III. In 734 B.C.E. the Assyrian ruler stormed the Near East, conquering the kingdom of Aram-Damascus, the Golan, Galilee and Gilead (southeast of the Galilee and beyond the Jordan). A little more 053than a decade later, his successor, Shalmaneser V, would conquer the northern kingdom of Israel and deport many of her residents, creating the storied Ten Lost Tribes. Two decades after that, the Assyrian ruler Sennacherib wreaked havoc upon the kingdom of Judah; in Assyrian annals, he boasts that he destroyed 46 Judahite cities and laid (an unsuccessful) siege to Jerusalem.b

The southern tower also contained a cultic niche, this one with a shelf 5 feet high, which may have served as a Biblical bamah, or high place. A sloping ramp led up to the niche, perhaps in accordance with the Biblical injunction: “You shall not go upon steps of my altar so that you reveal your nakedness thereon” (Exodus 20:26).

Is it possible that the two high places at the inner gate represented something of a religious compromise at Bethsaida, with moon worshipers walking up the steps to the northern high place and Israelites—perhaps emissaries of the Judean king in Jerusalem or Israelites married to residents of the city—using the ramp to the southern high place?

Between the two towers of the inner gate lay a threshold made of large dressed stones. At its center we discovered a semicircular stop-stone, which kept the gate’s massive doors from swinging too far out.

The pavement inside the gateway shows signs of erosion. Oddly, there is no evidence of wheels on this pavement; chariots and wagons must not have entered ancient Bethsaida with any frequency. Wooden beams were originally embedded horizontally between the stone courses of the inner gate. Although the beams themselves were burned by fire, we found a 10-inch-high recess for the beams along the walls of the gate about 5 feet above the ground. The beams absorbed shock in case of earthquakes. They appear to have worked: We saw no evidence of earthquake damage here, which is not the case elsewhere at Bethsaida where this technique was not used.

The destroyed upper stories of the inner gateway preserved the gate chambers below (see photo and plan). These chambers were important public centers in ancient Bethsaida. The two chambers at left when entering the city (on the southern side of the gate) measured 12 by 35 feet; those on the right (on the northern side) were slightly smaller, measuring 12 by 32 feet. The walls of the rooms were 8 feet thick. A chamber on each side of the gate was used as a granary. In one (room 3 on the plan), we found one ton of burnt barley! We hoped to find some insects among the barley so that we could pinpoint the month of the destruction, but we found none.

Further evidence of the Assyrian attack came from the adjacent chamber (marked 4 on the plan), where we discovered 15 arrows and spearheads, numerous broken pottery sherds, and a thick layer of ash. Among the debris we found ritual vessels, including incense burners and a jug inscribed with the phrase “in the name of” followed by an ankh-like symbol slightly different from the very common Egyptian sign for life. This room must have had a cultic function (it shared a wall 054with the stepped high place, which stood just on the other side of the wall).

In chamber 1 we found almost nothing; this room had been disrupted by a trench built by the Syrian army in the 1950s (the site was captured by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War).

We believe that under Bethsaida’s ninth-century B.C.E. gate lies a tenth-century B.C.E. gate. Ground-penetrating radar tests carried out last season show that there are thick walls and paved floors below the courtyard of the ninth-century gate.

A palace just inside and to the right of the gate is the largest structure from ninth-century B.C.E. Bethsaida. A vestibule just inside the entrance led into the main room, which was probably a throne room. Eight other rooms, some of them well preserved, surrounded this main room. In all, Bethsaida’s palace measures 50 by 92 feet, with walls 4.6 feet thick.

Inside the palace we found a faience figurine of the Egyptian dwarf god Pataikos, a protective deity and an offspring of Ptah, one of the most important gods in the Egyptian pantheon. Outside the northern wall of the palace we found two ninth-century B.C.E. Phoenician-style bullae (lumps of clay impressed with a seal) that once sealed documents sent to Bethsaida from one of the Phoenician coastal cities or, perhaps, from Samaria, the capital of the northern kingdom of Israel. The bullae featured animal forms typical of classic Egyptian designs—a griffin, cobra and hawk—but executed here in Phoenician style.

One ostracon (an inscribed potsherd) from the eighth century B.C.E. bears the name Akiba, the Aramaic form of Jacob. This is the earliest occurrence of the name made famous by the second-century C.E. rabbi Akiba, who among other things, was a champion of the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 C.E.). An inscription on a handle from the palace bears the name Machy, short for Michyahu, which means “Who is like Yahweh?” (Yahweh is the personal name of the Israelite God). The name of the prophet Micah may be a shortened form of this name.

Another handle was stamped with the name Zechario (meaning “Remembered of Yahweh”). A similar stamp was found at Tel Dan, about 50 miles north of 055Bethsaida. Avraham Biran, Dan’s venerable excavator, suggests that this stamp might refer to Zechariah, the son of Jeroboam II, who ruled Israel for only six months in 748 B.C.E. Since royal stamps generally include the title with the name, we conclude that this stamp probably dates to a time before Zechariah became king (assuming that it is the same Zechariah). The two Zechario stamps point to a connection between Bethsaida and Dan during the Iron Age, a relationship more strongly shown by similarities in architecture, fortifications, high places, gate complexes and pottery.

Strangely, the palace seems not only to have survived the Assyrian conquest, but to have enjoyed several renovations thereafter. The main hall was divided in two, and a thick wall was built in the plaza in front of the building. We do not know why the palace was altered.

Although Bethsaida continued to be occupied after Tiglath-pileser’s conquest, it was much smaller and never regained its former prominence.

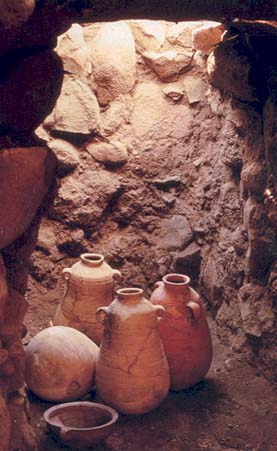

In the Hellenistic era (332–37 B.C.E.), thanks to Bethsaida’s location between the powerful Seleucid and Ptolemaic Empires, the former to the north, the latter to the south, the city revived. From this period we excavated a residential quarter of private homes, each of which had several rooms surrounding a roughly paved courtyard. The kitchen was typically east of the courtyard, with the dining room to the north; the bedrooms were probably on a second floor.

In one house, which we call the Fisherman’s House, we found lead net weights, anchors, needles and fishhooks. One fishhook had not yet been bent, indicating that it was manufactured at the site. We also found a clay seal that depicts two figures casting a net from a hippos boat—a Phoenician-style ship with a horsehead-shaped prow. The scene seems to be set in shallow, reed-filled water rather than on the open sea, an indication that it depicts a view near the shore. The seal now serves as the logo for the Bethsaida Excavations Project.

A second house boasted a wine cellar with four large wine jars and pruning hooks. We dubbed it the Wine Maker’s House.

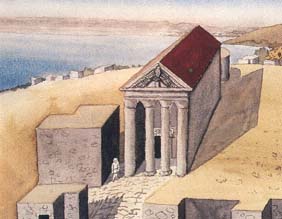

In the first century C.E. Bethsaida enjoyed one last period on the historical stage: It played an important role in Jesus’ Galilean ministry. It played a much smaller role in Roman history, as a provincial city on the periphery of the empire. The first-century C.E. Jewish historian Josephus relates that in 30 C.E. Philip, son of Herod the Great, elevated Bethsaida to the status of a city and renamed it Julias, in honor of Julia-Livia, wife of the emperor Augustus and mother of the then-reigning emperor, Tiberius. Our excavation has uncovered a temple that may be related to this event.

The temple, located partially over Bethsaida’s ninth-century B.C.E. gate, follows a common Roman temple 056plan: a columned porch (we have found one column so far), a pronaos (approaching hall), which leads into a long, rectangular naos (holy of holies), followed by a small room in the back, called the adyton, which was used as a back porch. The walls were built of dressed stones decorated with rosettes; we found some of the stones in secondary use in nearby Bedouin tombs.

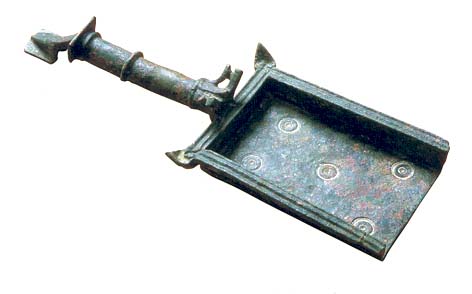

Among the finds were two bronze incense shovels.c These shovels are similar to those used in other Roman temples, but they also resemble incense shovels depicted in synagogue mosaics from the Byzantine period.

A figurine excavated near the temple portrays a woman wearing a veil, indicating that she is involved in a religious ceremony. This figurine, another of a woman with a veil adorned by a diadem, and three coins depicting Philip may have been created for the city’s renaming ceremony.

Near the temple lay a lintel bearing a frieze with meander and floral motifs. We also found stones decorated with scrolls of leaves and an acanthus floral motif. They probably came from the temple. But they are very similar to stones in the fifth-century C.E. synagogue at Chorazin, only 3 miles away.d Because Bethsaida was not occupied during the Byzantine period, we suspect that the stones from Bethsaida’s temple to Julia-Livia were reused in the Chorazin synagogue! The synagogue is precisely the width of the Bethsaida temple. Even more striking, the Chorazin synagogue’s pediment contains an eagle—the symbol of Roman imperial power! This strengthens our belief that elements of Bethsaida’s Roman temple were reused in Chorazin.

Changes in the Galilee shoreline placed Bethsaida farther and farther from the lake and eventually led to the city’s abandonment in the third century C.E. There it slumbered in silence for nearly 2,000 years.

Bethsaida is the town that disappeared. Soon after playing a prominent role in the Gospels—Bethsaida is mentioned more often in the New Testament than any city except Jerusalem and Capernaum—this fishing village on the Sea of Galilee simply became lost to history. Early Christian pilgrims went in search of it, but they had no idea where to find it. Even in modern times, three different sites north of the Galilee have been proposed as ancient Bethsaida. Happily, however, we can report that Bethsaida has been found once again. And not only have we rediscovered the village of Jesus’ time, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Ground-penetrating radar uses radio waves to “see” below the surface, much like X-ray machines provide images of the inside of bodies.

See William Shea, “Jerusalem Under Siege,” BAR 25:06.

See Rami Arav and Richard Freund, “Prize Find: An Incense Shovel from Bethsaida,” BAR 23:01.

See Ze’ev Yeivin, “Ancient Chorazin Comes Back to Life,” BAR 13:05.

Endnotes

Rami Arav began the Bethsaida Excavations Project on behalf of the Golan Research Institute under the auspices of Haifa University. In 1991 the Consortium for the Excavations Project was formed. Today the consortium consists of 17 universities and colleges throughout America and Europe and is jointly sponsored by the University of Nebraska at Omaha and the University of Hartford.

We have collected references to 20 earthquakes, both major and minor, going back to the first century B.C.E. The most recent review is David Amiran, E. Arieh and T. Turcotte, “Earthquakes in Israel and Adjacent Areas: Macroseismic Observations since 100 B.C.E.,” Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ) 44:3–4 (1994), pp. 260ff. See also the original report by D. Amiran, “A Revised Earthquake Catalogue of Palestine,” IEJ 1 (1950–1951), p. 225ff; and Ehud Netzer, Greater Herodium, Qedem 13 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), pp. 28, 134 n. 22.

The same geological phenomena that led to Bethsaida’s demise also contributed to the disappearance of other ancient ports, such as Ephesus and Miletus in Asia Minor. In addition, declining water levels have isolated former ports near inland seas, including along the Aral Sea of central Asia and near ancient Lake Seistan (now Dasht-Margo, or Desert of Death), in southwest Afghanistan.

Work on the geological and geographic questions at Bethsaida began in 1992. John F. Shroder, Jr., and Michael Bishop, of the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Department of Geography and Geology, together with Moshe Inbar of the Department of Geography at Haifa University, led the investigations. The surveys at el-Araj have revealed that the sedimentation contains a mix of Hellenistic and Roman period finds, which were deposited there as a result of catastrophic flooding of the Jordan River following earthquake activity.

Our team includes geologists, geographers, hydrologists, archaeologists and historians. Geoarchaeologists have helped us grapple with processes that span thousands of years. Our work ranged from the very large—26 trenches cut by backhoes and a series of test boreholes dug from the bottom of the et-Tell mound to the Sea of Galilee—to the minute—carbon 14 tests on microorganisms. Our project has been the most extensive investigation ever of the north shore of the Sea of Galilee.