016

The thousands of mid-second-millennium B.C. documents unearthed at Boghazkoy, Turkey, the site of the Hittite capital of Hattusha, include several collections of myths dealing with ancient heroes and gods. In the most important group of these myths, however, the heroes and gods are not Hittite; they are Hurrian, and their stories are set not in Anatolia but in Syro-Mesopotamia, where Hurrian-speaking people lived. These myths, the so-called Kumarbi Cycle, are Hittite translations of Hurrian stories. Some of them are even inscribed on bilingual tablets in both Hittite and Hurrian.

018

The Kumarbi Cycle consists of stories about one of the principal Hurrian gods, Kumarbi, and his family. (The Hittites took Kumarbi’s son Teshub, the storm god, as their main god.)a Kumarbi rules over a city named Urkesh. In one story, Kumarbi’s son Silver is sent to live with his mother in the mountainous countryside, where another child, an orphan, torments him by telling him that he has been abandoned by his father and that he, too, is just an “orphan”:

Weeping, Silver went into his house. Silver began to repeat the words to his mother … His mother turned around and began to reply to Silver, her son … “Your father is Kumarbi, the Father of the city of Urkesh … Your brother is Teshub. He is king in heaven. Your sister is Shauska, and she is queen in Nineveh. You must not fear any other god; only one deity (Kumarbi) must you fear” … Silver listened to his mother’s words. He set out for Urkesh, but he did not find Kumarbi in his house. Kumarbi had gone off to roam the lands.1

We know that Urkesh was not just the central city of Hurrian myth. It was a real city as well. In 1948, two bronze lions appeared on the antiquities market; the lions are inscribed with a text in which a king by the name of Tish-atal boasts of having built a temple in Urkesh. But since the provenance of these lions is not known, the location of the city until recently was also unknown.

Our excavations, however, have proved that Urkesh was located at the remote north Syrian site of Tell Mozan. There we have found a number of short Hurrian inscriptions, mostly on seal impressions, or bullae—lumps of moist clay impressed with seals (which, at Tell Mozan, are cylindrical in shape) to secure documents or shipments of goods. The name “Urkesh” appears on several seal impressions that also give the name and Hurrian title of the king: “Tupkish, the endan (king) of Urkesh.” Here, then, is the city made famous in the ancient Near East by the elegant religious lore of the Hurrians.

We began looking for a Hurrian site to excavate in the early 1980s. Although we were interested in the Hurrians, we were not specifically looking for Urkesh—just for a third-millennium B.C. city that might tell us about Hurrian urban civilization. At that time, very little was known about the enigmatic Hurrians, and there are still many gaps in our knowledge. The name 019“Hurrian” refers to a language found in Syro-Mesopotamia during the third and second millennia B.C. Its only known relative is Urartian, a language attested in eastern Anatolia in the ninth and eighth centuries B.C.b As a result of our excavations, we believe that Hurrian speakers, or Hurrians, were present in northern Syro-Mesopotamia at least by the beginning of the third millennium B.C. They adapted the cuneiform script devised by the Sumerians—and used by the Babylonians and Assyrians to write forms of Akkadian—to write their own language.

Until recently, almost nothing was known about the Hurrians as an ethnic group (see the second sidebar to this article) or a political entity. That is one reason we hoped to find an early Hurrian city that might enlighten us about the origins of these people.

Tell Mozan was promising. It was the only large third-millennium B.C. site in the general area from which the lions of Tish-atal were reputed to have come and where Hurrian myths seemed to situate Urkesh. Tell Mozan had previously been investigated, but only briefly. The British archaeologist Max Mallowan, husband of the mystery writer Agatha Christie, surveyed the site in 1934. He dug three trenches and noted some surface remains. The most detailed account of Mallowan’s work at Tell Mozan is in Christie’s memoir Come Tell Me How You Live, in which she reports that he interpreted the tell as Roman and moved on to another site. For years, on the strength of Agatha Christie’s brief description, Tell Mozan had a reputation as a Roman-period site.

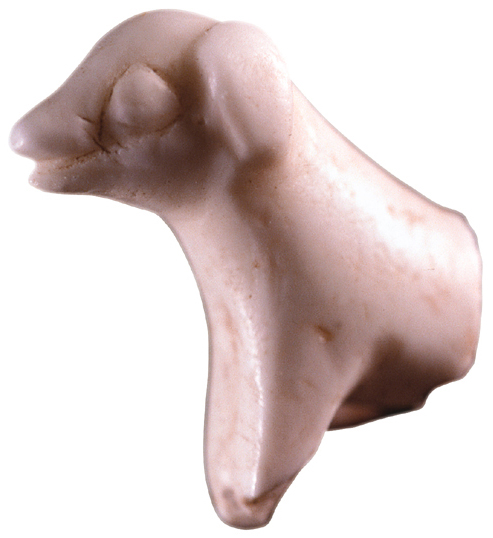

In 1984 we began excavations at the tell. Almost immediately we discovered a large temple lying near the surface at the top of the mound, which rises some 80 feet above the surrounding plain. From associated seal impressions and pottery we dated this 020temple to about 2500 B.C. Enclosing the tell was a city wall more than 20 feet high and 25 feet thick, dating to around 2600 B.C. Although our initial surveys turned up only scant architectural remains and few objects—a stone lion, a stone relief associated with the temple and some seal impressions—we knew that this was just what we were looking for.

Our major discovery came six years later. In the 1990 season we cut a stepped trench on the western side of the mound, which ends in a large flat area at the base of the tell. Here the line of squares forming our trench traversed a series of rooms. It was a well-preserved building, which we later determined was the royal palace. The accumulation above the floor contained numerous seal impressions. By 1998 we had found almost 2,000 sealings, about 170 of them inscribed. All the inscribed seals are “royal”—that is, they refer to the king, the queen or one of their courtiers—and they present an intimate tableau of Hurrian court life toward the end of the third millennium B.C.

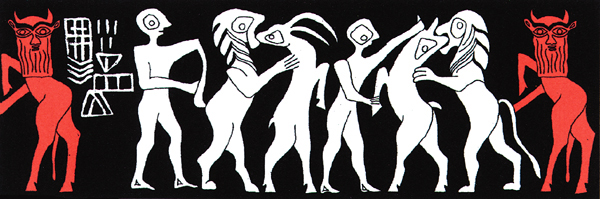

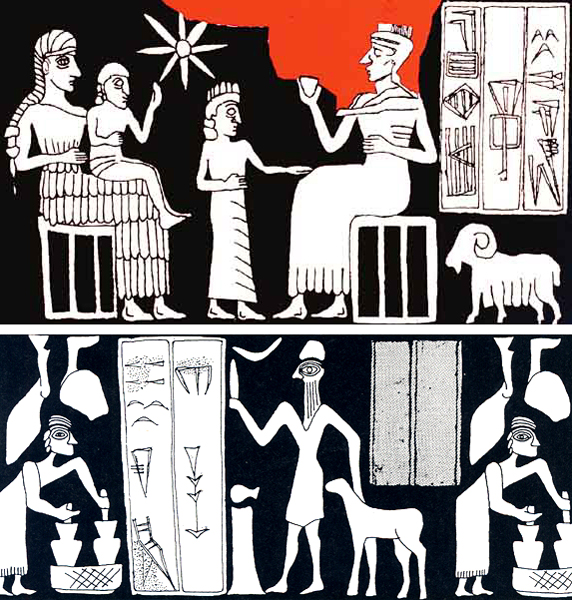

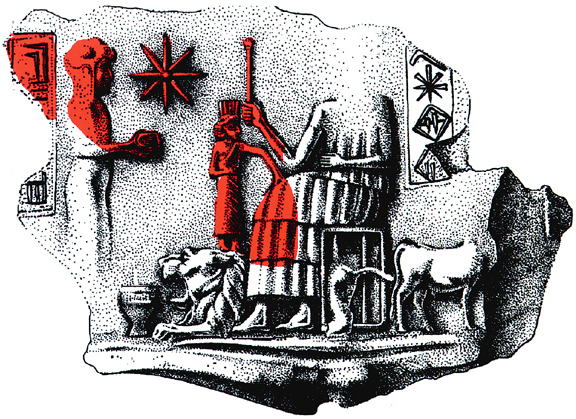

We now have seven impressions belonging to the king. In one fragment, courtiers offer the king presents or tribute, including what appears to be a skein of wool. Another extremely elaborate bulla (see photo and reconstruction drawing of bulla) shows the king seated, with a lion crouched under the throne. At Urkesh, as throughout the Near East, lions often represented royal authority. On our bulla, a child stands on the lion’s mane and touches the king’s lap. The child’s association with the lion probably identifies him as the crown prince; in touching the king’s lap, he is confirming a pledge made to the king, his father (similarly, in Genesis 24:2, Abraham instructs his servant to confirm a vow by placing his hand “under his [Abraham’s] thigh”). One last element completes the scene on the impression: Standing before the king is a rigid, formal, humanlike figure holding an offering cup over a larger bowl. Given that this elegant figure is associated with an eight-pointed star, and that a bull behind the king is looking not at the king but at the standing figure (remember that the 021original seal was cylindrical), it may be that the figure represents a deity. The image on the bulla, then, provides an intimate view of future dynastic succession, with the son fulfilling the wishes of the father. If the standing figure is divine in nature, then it also suggests a more cosmic theme: The gods fill the bowl from which the lion, symbol of kingly power, drinks.

Ten seal impressions belong to the queen. One is inscribed “Uqnitum, the wife of Tupkish”—and we know that Tupkish is the king, so Uqnitum is his queen. This bulla (see photo and drawings of bulla depicting Urkesh’s royal family) contains a lovely family portrait: On the right side, the crown prince—almost identical to the youngster in the king’s seal—again touches the lap of the enthroned king; on the left, the mother-queen, seated on a level with the king, holds a small child on her lap. In another seal, which reads “Uqnitum, the queen,” the frame with the inscription runs horizontally over the bent back of the queen’s servants, as if to declare visually her power.

If, as was usually the case in Near Eastern royal families, Tupkish had more than one wife, the queen’s seals may have served as campaign ads, so to speak. Uqnitum would naturally have wanted her own son to succeed to the crown, so she may have had seals carved depicting the royal family as an ensemble—and inscribed not only with “wife of Tupkish” but also with the more regal “queen,” or the mother of the crown prince.

We have bullae showing a whole range of court activities. One belongs to the king’s majordomo (literally, the throne-bearer); another, to Queen Uqnitum’s nurse, Zamena. We found a sealing depicting the royal cook churning butter and the royal butcher slaughtering a goat. Another intriguing scene on one of our seal impressions shows a lively animal combat scene, a theme frequently found in the Akkadian south—possibly this seal was carved in Akkad and belonged to a visiting Akkadian dignitary. In short, the entire royal court is involved in this assemblage of sealings with 022its rich and complex typology. The multiplicity of examples suggests that Urkesh was indeed the central city of a Hurrian kingdom, just as the myths describe. Although we do not yet know how far Urkesh’s power reached, this kingdom was a substantial, complex political entity in the third millennium B.C.

How do we know that the sealings were not simply dumped at Mozan? Could they have come from somewhere else? No. The coherence of the assemblage—including several depictions of the crown prince, repeated references to “Uqnitum” and “Urkesh,” the seals’ similarity in design, and the use of the Hurrian language in the inscriptions—suggests that it was the product of a single, organized Hurrian polity.

The most critical evidence, however, has to do with where the impressions were excavated. We found them in the accumulation on the first floor of the building—that is, the floor put in place right after the construction of the walls. The impressions were not deposited en masse; rather, they were scattered on the floor over time and remained where they had fallen. Shipping containers arrived at the site from various parts of the kingdom, or sometimes from foreign kingdoms (we found a bulla with the impression of a seal that probably had been carved in southern Mesopotamia, showing an Akkadian motif of the sun god Shamash rising). These containers were marked for the king, the queen or the royal administration, and then they were put into storage. When they were opened for use, fragments of the sealings were scattered over the floor—for us to find some 42 centuries later. There can be no doubt that the “Urkesh” mentioned in the sealings is the site where they were found.

Our excavation of these seal impressions is emblematic of our work, and possibly of the work of archaeologists in general. We have uncovered a large area, and yet so much of our information comes from these tiny fragments. The cylinder seals (and impressions) from Urkesh are never more than an inch high; and since we find only fragments, we generally deal with pieces 023about the size of a thumbnail. We have collected about 10,000 clay lumps resembling seal impressions. These lumps are found in a matrix of clay not unlike the clay from which the sealings were made, so we cannot clean or study them on the spot, but must wait until they dry out in the laboratories of our field house. Of the 10,000 lumps collected, so far some 2,000 have turned out to be impressions—and only four of these contained the name “Urkesh,” allowing us to identify the site. The daunting contrast between the vastness of the dig, with tons of excavated material, and the minuteness of the key fragments is a source of pride: Only trained archaeologists working with our methods could retrieve and make sense of these data.

Besides identifying Tell Mozan as Hurrian Urkesh, our excavations demonstrate that Hurrian civilization developed in northern Mesopotamia much earlier than formerly believed. For example, a distinguished encyclopedia of Near Eastern archaeology, published just four years ago, observes that the evidence indicates “a Hurrian presence in northern Syria and Anatolia as early as 2000 B.C.E.”2 That is the common view: that the first Hurrian kingdoms, including Urkesh, came into existence at the very end of the third millennium B.C. as a result of the collapse of the Akkadian Empire in southern Mesopotamia.

The evidence we continue to uncover, however, keeps pushing back the origins of Hurrian civilization in northern Mesopotamia. 024The temple built at the summit of the tell, as we have seen, dates to 2500 B.C. Moreover, this temple was not an isolated structure, as excavations carried out in 1998 showed.

On the plain at the northern edge of the site, we had to make a sounding because a local farmer wanted to dig an irrigation well. Here we discovered evidence of an administrative building containing material identical to that found in the temple. For the farmer, this meant that he could not dig his well (a decision he accepted most graciously). For us, it meant that by the middle of the third millennium B.C. this Hurrian site was not confined to official buildings on the high mound but extended down to the plain. By 2500 B.C., Urkesh was a formidable urban center occupying almost 300 acres, one of the largest in Syria during this period. This may not seem very big to a modern city dweller, but it was bigger than Ebla, one of the great centers of ancient Syro-Mesopotamia.

Also in 1998 we were joined by a team from the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German Oriental Society), directed by Peter Pfälzner of Tübingen University, which has undertaken a three-year project to investigate domestic architecture in ancient Urkesh. The German team cut a long trench from the temple to its own excavations south of the temple. This trench uncovered evidence 025of a huge stone and brick platform (or terrace), which dates to about 2700 B.C. The ancient platform rose, ziggurat-like, to a height only slightly lower than the present summit of the tell. On top of the platform, presumably, rested an earlier temple, which would have been visible for miles. As early as 2700 B.C., then, a Hurrian temple may have soared into the Syrian sky from a magnificent pedestal.

This is as far as our excavations have taken us. We suspect, however, that the platform, too, was built on top of an even earlier structure—pushing the origins of Hurrian urban life back to the early third millennium B.C. If so, the Hurrians began building their cities around the same time that the Egyptians, hundreds of miles to the southwest, began to build their dynasties.

So far, only a few Hurrian urban centers 026have been found. There is a narrow strip of land flanking the lower ridges of the Taurus mountains that we call the Hurrian “urban ledge.” All of the Hurrian cities of the third millennium B.C.—especially Tell Chuera, Urkesh, Nineveh and (further east) Kumme, as they are named in Hurrian myths—were located along this ledge.

This urban ledge forms an arc at the southern edge of a mountainous area extending north into the Anatolian plateau. It thus lies at the border of a vast hinterland, where materials that were essential to early urban civilization were found: copper for making weapons,c and timber and stone for building houses, temples, walls and palaces. The Hurrian cities were, in a sense, gateways to the southern Mesopotamian urban centers. There were relatively few of them, but they were strategically located along the arc that controlled access to the mountain hinterland. This hinterland, we believe, is the Nawar mentioned in an inscription of another king, Atal-shen, “king of Urkesh and Nawar.”

In the third millennium B.C., the mountainous hinterland adjacent to the Hurrian cities had no large urban settlements. Probably the inhabitants were also Hurrian—living in villages or small towns, but tied by language and tradition to the cities on the urban ledge, including Urkesh.

The Hurrian “Song of Silver,” we believe, can be read as an allegory describing precisely this ethnic situation. The boy Silver is sent from Urkesh to live with his mother in the mountainous countryside, where he plays with the other boys but also comes into conflict with them. His father, the god Kumarbi, resides in Urkesh, a sort of ancestral home. The story suggests a kind of kinship relation between the people of the mountains and the people of the city. Ancient Hurrians may well have recognized their own linguistic and ethnic ties to the mountain loggers and 027copper miners in Silver’s pilgrimage to Urkesh.

The kings of Urkesh could count on their ethnic ties with the mountain populations to ensure access to resources—even if the kings exerted no direct administrative or military control over the rural hinterland. This kind of arrangement gave the Hurrians a certain advantage. For example, in centrally organized states, the outlying territories are controlled through military outposts or bureaucratic administrations. If such a state is conquered, the outlying areas are taken over as well. The conquest of a Hurrian city like Urkesh, however, would not entail control over the mountain hinterland, for the mechanisms of control were ethnic and thus not transferable to the conquering power. This may account for the fact that the Akkadian kings never boast in their extensive military accounts of having conquered any Hurrian cities.

With our excavations, one of those cities is gradually coming to light. As we learn more about Urkesh, we also learn more about the amazing, if largely unknown (at least to the non-archaeological world), Hurrian civilization. Some 5,000 years ago, when the Sumerians and the Akkadians were building new urban cultures in the south, so were the Hurrians in the north. And their influence continued long into the second millennium and spread to wider geographical areas. In late-second-millennium B.C. Ugarit on Syria’s Mediterranean coast, archaeologists have found the world’s first known musical score, used to record the tune of a Hurrian religious hymn. Our excavations at Urkesh will continue to bring even more about the Hurrians to light!

This article is adapted from a longer manuscript by the authors.

The thousands of mid-second-millennium B.C. documents unearthed at Boghazkoy, Turkey, the site of the Hittite capital of Hattusha, include several collections of myths dealing with ancient heroes and gods. In the most important group of these myths, however, the heroes and gods are not Hittite; they are Hurrian, and their stories are set not in Anatolia but in Syro-Mesopotamia, where Hurrian-speaking people lived. These myths, the so-called Kumarbi Cycle, are Hittite translations of Hurrian stories. Some of them are even inscribed on bilingual tablets in both Hittite and Hurrian. 018 The Kumarbi Cycle consists of stories about one of […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See E.C. Krupp,“Sacred Sex in the Hittite Temple of Yazilikaya,” AO 03:02.

Most scholars believe that Hurrian and Urartian derive from a single language and that these two branches broke off sometime in the late fourth or early third millennium B.C.