Climbing Vesuvius

040

041

Mount Vesuvius sleeps quietly today, overlooking the brilliant blue waters of the Bay of Naples. Yet over the millennia its eruptions have again and again destroyed (and sometimes preserved) towns lying near its slopes—including the prosperous ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

042

No one visits Naples without seeing Pompeii, the sprawling Roman city of baths and brothels, theaters and temples and shops and villas, discovered in the 18th century beneath the ashes of Vesuvius. Many fewer take the better part of a day, as we did, to climb Vesuvius and to visit nearby Herculaneum. There, without the immense number of tourists one experiences at Pompeii, and in much smaller surroundings, one can walk the streets of a Roman city where life froze, so to speak, on August 25, 79 A.D.—completely submerged in a lava flow that buried thousands of people.

If in antiquity Pompeii was the bustling commercial hub, Herculaneum was the opulent seaside getaway for Roman patrician families. The Roman philosopher Seneca (c. 55 B.C.–40 A.D.) observed of Herculaneum: “We think ourselves poor and mean if our walls [of the baths] are not resplendent with large and costly mirrors; if our marbles [statues and busts] are not set off by mosaics of Numidian stone, or their borders are not faced over on all sides with difficult patterns, arranged in many colors like paintings; if our vaulted ceilings are not buried in glass; if our swimming pools are not lined with Thasian marble, once a rare and wonderful sight in any temple; and finally, if the water has not poured from silver spigots.”

Vesuvius, whose crater is called the Gran Cono, is actually a 4,000-foot volcano within the crater of another, more ancient volcano, the Monte Somma. The dead and fractured Monte Somma is now intact only on its northern rim, which is separated from its explosive offspring by two 043valleys with expressive Italian names, the Valle del Gigante and the Valle dell’Inferno.

Despite Vesuvius’s formidable profile, its summit is relatively easily reached—even for those not ready to hike the long route up from the base of the mountain. We drove to the entrance of the Vesuvius National Park through the hillside town of Torre del Greco. Elegant homes and winding arbors belie its history of multiple destructions, with smoking lava racing through its tree-lined streets toward the sea. The road winds up the slopes of Vesuvius, past vineyards from whose grapes come the famous 044Lacryma Christi (Tears of Christ) wine, past glorious displays of the brilliant yellow flowers of broom shrubs flashing against the black volcanic earth, to a parking area where the hike begins.

At the gate, climbers receive walking sticks as they set off on the broad packed-gravel trail. A gradual steady climb moderated by switchbacks brings you after about 40 minutes to the ticket booth where payment of 10,000 lira (about $4.50) allows access to the final stretch. It comes as a lovely surprise, especially on a blazing summer day, to turn the corner of a rock outcrop and suddenly peer over the edge of the black, silent, stratified crater—1,650 feet in diameter and 985 feet deep.

Every 50 years or so Vesuvius springs to life. Its fury last spewed forth in March 1944, during World II. For a month it displayed its awesome repertoire—a huge spiral cloud of smoke, volcanic ash covering villages as well as planes on the ground at a nearby U.S. Air Force base, glowing avalanches, landslides, earthquakes and molten lava flows forcing the evacuation of towns. On April 7, 1944, the eruption ended, and the mountain is still at rest today, almost 60 years later. Italian archaeologist Amedeo Maiuri visited Vesuvius in 1956 and wrote in Passeggiate Campane: “After the tremendous convulsion [of 1944] the volcano, overpowered by its own violence, has become a difficult patient that does all it can to hide its real state of health. In inhales and exhales just enough to keep itself alive and recoup its forces … ‘It’s not lethargy,’ says observatory director Imbo, ‘It’s Vesuvius’s dynamic repose.’”

Whether Vesuvius has entered a long 045dormancy or whether the historic cycle will one day begin again is unknown. But the bright golden broom flowers decorating the mountain remind us that Vesuvius is more than a carrier of death and desolation; it is also a life force, bringing to those million people who live in its shadow the gift of fertile soil, nurturing vineyards, citrus groves and more than 900 varieties of flowering plants.

But 2,000 years ago, in the summer of 79, Vesuvius was bent on death. On August 24, as described in the letters of Pliny the Younger, a gigantic cloud shaped like a Mediterranean umbrella pine rose 20 miles over Vesuvius.a Driven by wind, the cloud rained a foot of pumice and ash on Pompeii every two hours. Because the people of Herculaneum, only 4.5 miles from the crater, did not experience the pumice cloud that hit Pompeii, they were lulled into believing that they need not flee. On the following day, however, the volcanic cloud column collapsed and the eruption changed to a massive lava flow that roared 60 miles per hour toward Herculaneum, sending panicked people on a futile flight toward the sea. An hour later, another flow buried anyone who had survived the first. Recently, the remains of 48 people who had tried to outrun advancing lava were found on the Herculaneum beach. Scientists contend that they died not from suffocation but from a blast of searing 750-degree heat. The lava hardened around the victims, leaving a mold of their bodies down to the finest details. By injecting silicone and then plaster into the now-empty stone mold, exact models can be made of the terrified people at the moment of death.

048

The traditional account of the events of 79 is that the eruption came without warning. Today we know that an earthquake in 62 A.D., which badly damaged Pompeii and Herculaneum, probably opened passages deep within the mountain that prepared the way for molten magma to break through the surface 17 years later. People went about repairing the earthquake damage, but unfortunately did not heed its warning.

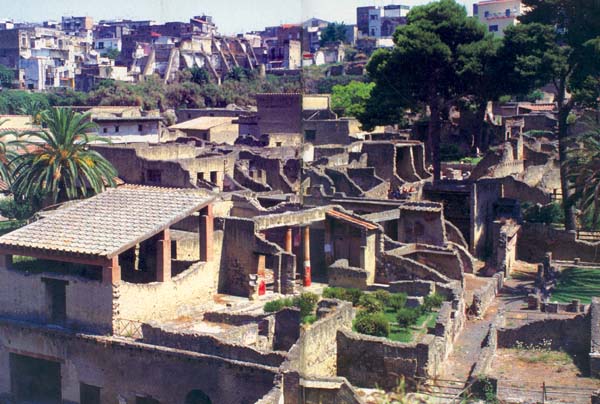

Clearly visible from the summit of Vesuvius, Herculaneum, only a few miles from the base of the mountain, is a natural next stop. The entrance to the scavi, or excavations, is through a tunnel cut into a huge wall of volcanic rock. The wall’s height, well over twice that of the two-story villas now exposed in the ancient city, shows what faced the first excavators of Herculaneum. These early explorers cared little about rediscovering the buried city—they were looking for loot. The practice of tunneling in order to plunder art from buried villas was begun in 1709 by Prince Elbeuf, an officer in the Austrian legion that was occupying the area around Pompeii. Thereafter, mosaics, wall paintings and other artifacts were extracted for the collections of the Bourbon kings of Naples.

By the middle of the 20th century, the tunnels had collapsed and the location of the villas of Herculaneum was largely forgotten. Not until 1950 did scientific 049excavations begin to unearth the ancient city. Today, Herculaneum invites visitors to stroll about its streets, enter its bath houses, imagine athletic events in the city-block-size palaestra (sports arena), and peer into elegant houses whose wooden beams were often preserved by the lava inundation. Unlike Pompeii, which is exhausting and requires more than one visit to see everything, Herculaneum is graspable, because excavations there have been limited by the living city that surrounds it.

There’s much more to expose at Herculaneum, which recently was added to the United Nations’ list of World Heritage Sites. But money is needed to continue the excavation. To find those resources, the mayor of Ercolano, the modern city where Herculaneum is located, and Italy’s minister of cultural affairs have put the ancient site on the market. (An Italian law called the Veltroni Law permits certain state-owned companies and moneymaking entities to be sold or transferred to private ownership.) If a sales agreement is reached, the new owner of Herculaneum will receive the right to excavate the site and take possession of artifacts that are recovered. Over the last couple of years, however, the uncertainty over Herculaneum’s future has made it difficult to find funding to pay the staff’s salaries or to undertake needed maintenance projects.

Let’s hope that Herculaneum’s “For Sale” sign comes down soon and that its new owner uncovers and preserves even more of its remarkable treasures.

Mount Vesuvius sleeps quietly today, overlooking the brilliant blue waters of the Bay of Naples. Yet over the millennia its eruptions have again and again destroyed (and sometimes preserved) towns lying near its slopes—including the prosperous ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See “The Day the Earth Shook,” Past Perfect, AO 04:03.