Conversion, Crucifixion and Celebration

St. Philip’s Martyrium at Hierapolis draws thousands over the centuries

034

The apostle Philip was hung on a tree upside down with irons in his heels and ankles in Hierapolis in Asia Minor.

One of the 12 apostles, according to all four Gospels, Philip was born in Bethsaida on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee (John 1:44, 12:21). His later career, after the Resurrection, is recounted in the apocryphal Acts of Philip.

Philip was dispatched with his sister Mariamne and Bartholomew, another apostle with whom he is often paired, to preach in Greece, Syria and Asia Minor. In Phrygia in western Asia Minor, the threesome came to Ophiorhyme; that is, “Serpent’s Town,” so-called because the inhabitants worshiped serpents and a viper called Echidna. Images of the viper and serpents filled the town, including the serpent temple with its statue of Echidna. The preaching of Philip and his colleagues, however, brought many of the townspeople to Jesus.

035036

When Nicanora, wife of the pagan proconsul, fell ill with various diseases, especially to her eyes, she too became a Christian under Philip’s influence. On one occasion Philip spoke to her in Hebrew, and she cried out, “I am a Hebrew and a daughter of the Hebrews; speak to me in the language of my fathers. For, having heard the preaching of my fathers, I was straightway cured of the disease and the troubles that encompassed me.”

Philip led a prayer for Nicanora:

Thou who bringest the dead to life, Christ Jesus the Lord, who has freed us through baptism from the slavery of death, completely deliver also this woman from the error, the enemy; make her alive in Thy life and perfect her in Thy perfection, in order that she may be found in the country of her fathers in 037freedom, having a portion in Thy goodness, O Lord Jesus.

This sent her husband, the proconsul and a worshiper of the snakes, into a fury. The text says he “raged like an unbroken horse.” He threatened her and called the Christians magicians. She urged “the tyrant” to convert: “Flee from the wicked dragon and his lusts; throw from thee the works and the dart of the man-slaying serpent,” she counseled her husband. If he would convert and “live in chastity and self-restraint, and in fear of the true God,” she would continue to live with him all her life; “only cleanse thyself from the idols and from all their filth.”

The proconsul again went into a rage. He would like nothing better, he said, than to see her “committing fornication with these foreign magicians.” He had Philip, Bartholomew and Mariamne beaten and scourged with thongs of raw hide and then dragged through the streets and, finally, brought to the serpent temple. Many of the townspeople who had converted to Christianity were brought with them. There they prayed and, according to the Acts of Philip, the pagan temple shook to its foundations.

The proconsul then had Philip, Bartholomew and Mariamne stripped and searched for the source of their “enchantments,” their magical powers that appeared to threaten the serpent temple. Mariamne they displayed naked so the people could “see her indecency, that she travels about with these magicians, and no doubt commits adultery with them.”

Philip and Bartholomew he ordered “hanged head downwards” with nails and iron hooks in their heels and ankles.

At the announcement of their punishment, Philip and Bartholomew smiled for “their punishments were prizes and crowns.” As for Mariamne, a cloud of fire enveloped her so that the crowd could not look at her nakedness.

038

In answer to Philip’s cry while hanging upside-down on the tree, an abyss suddenly opened and swallowed the proconsul and the viper temple where he was sitting, as well as the viper priests and 7,000 men, plus women and children. They promptly called to God from the depths of the earth, because “we now see the judgments of those who have not confessed to the Crucified One. Behold the cross illumines us. O Jesus Christ, manifest Thyself to us.” A voice replied, “I shall be merciful to you.” And all were restored.

Some of the faithful now ran to take Philip down from the tree. But Philip admonished them, “Do not, my children, do not come near me, for this shall be my end.” Philip alone expired on the tree. Bartholomew and Mariamne buried him there, and according to his instructions a church was built on the site. All the townspeople became Christian and the name of the town was changed to Hierapolis, “the Holy City.”

This account, based on the Acts of Philip, dates to about the fourth or fifth century. Many of the details, including which Philip (the apostle or the so-called deacon Philip, mentioned in the canonical Acts of the Apostles) was hung at the site, are contested and uncertain. Elements of the story are richly imaginative, legendary and symbolic. But a Christian following centered on the sainted Philip the apostle soon grew up at the site. And on his supposed grave was built one of the most remarkable structures in all of ancient Christendom—the martyrium of St. Philip.

Despite its imaginative elements, like so many ancient texts, the Acts of Philip is based on a realistic foundation, namely the unusual geological attributes of the site. Hierapolis is crossed by a highly active seismic fault associated with frequent earthquakes and hot springs. The modern name of the place, Pamukkale, is Turkish for “Castle of Cotton,” a name inspired by the white stone cascades near the site that recall the flower of the cotton plant. Earthquakes have opened up huge holes and given rise to additional hot springs that have resulted in these “cotton flowers,” which actually comprise the world’s most lavish travertine formation.

These geological phenomena have always defined the site. As early as the third century B.C. it was widely known as a thermal spa. The name of the city Hierapolis may have been connected with the place of the sanctuary of Apollo or perhaps with Hiera, wife of the son of Heracles. In any event, Hierapolis became a thriving Roman city dedicated to Apollo. Indeed, as this article was being written, we discovered a larger-than-life-size 039statue that may represent the god Apollo from this Roman city (see sidebar). His temple, the remains of which still survive, was the focus of the site. With three-dimensional Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) we have detected manmade structures under the temple. A prestigious oracle (similar to 040the one at Delphi) operated from Apollo’s temple. Ancient doctors treated the sick and the dying with the medicinal waters of the hot springs.

At its height the Roman city featured a theater that seated 6,000 people, elaborate baths, a gymnasium, several temples, imposing city gates, and a main thoroughfare 5,000 feet long with an arcade on either side.

When the city became Christian in the Byzantine period, numerous churches were built, especially as the city became a center of pilgrimage to the 041martyrium of Philip. One of the Roman baths was transformed into a basilical church. The great sanctuary of Apollo, which had for centuries represented the heart of the city and a center of attraction for a large part of Asia Minor, thanks to the prestige of its oracle, was systematically demolished by the new Christian ruling class: The marbles were used in other constructions or burnt to form construction lime, and the area became a dump for building waste.

The Acts of Philip reflects not only the site’s geological situation, but also the struggles within early Christianity, especially regarding the precise nature of Jesus the Christ. Montanus, a priest of the Phrygian cult of Cybele who had converted to Christianity, propagated his distinctive interpretation of Christianity known as the Montanist heresy that was rejected by the church hierarchy. The Montanist heresy originated in Pepousa, a town not far from Hierapolis, and was popular throughout Phrygia. The Montanists emphasized the avoidance of sin and the importance of chastity, even forbidding marriage. For those characteristics the Montanist heresy in turn was linked to conceptions of another ascetic Christian sect also developed in Phrygia, whose doctrine is known as Encratism, from the Greek encratès, Latin continens (“self-control”). Encratists were Gnostic dualists. They supposedly had secret spiritual knowledge. For them, evil resided in matter and the flesh. Only the spirit was pure. They practiced rigid discipline, abstaining from meat, alcohol and sex, even rejecting marriage. Women were the work of Satan, and wine was venom from the Great Serpent.

It was in this atmosphere that the cult of St. Philip developed. Some of these Montanist views can be detected in the summary of the Acts of Philip with which this article began.

042043

Philip’s martyrium, like most martyria (e.g., the apse of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem built over the cave where Jesus is said to have been born, St. Peter’s house in Capernaum and even the Dome of the Rock from which Muhammed ascended to heaven in Muslim tradition) is an octagon, an eight-sided structure. Philip’s martyrium at Hierapolis has been excavated as part of an Italian archaeological project that has been going on since 1957, under the direction of Professor Paolo Verzone and since 2003 under my direction.1

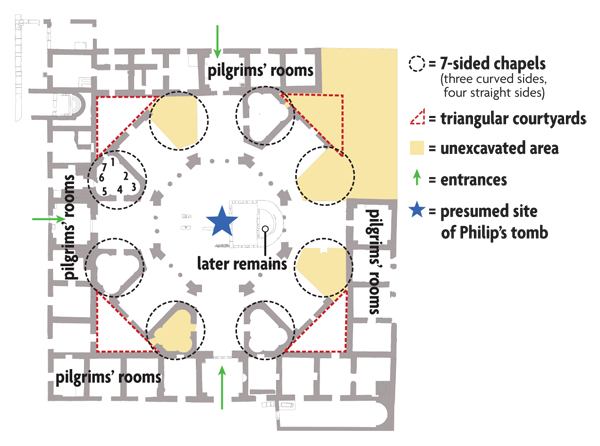

The octagon of Philip’s martyrium is enclosed in a rectangular portico, consisting of 28 small square rooms. Within the octagon are eight chapels, which end in four triangular courtyards in the corners of the outer rectangle. Each of these eight chapels is heptagonal, that is, with seven sides.

These numbers have symbolic meaning: According to church fathers such as St. Ambrose, the number eight (preserved in the octagon) is a well-known symbol for the Eon or eternity, time without end.

The number seven (preserved in the eight seven-sided rooms within the chapels) is pervasive as a symbol in the Hebrew Bible—from the seven days of creation to the seven branches of the Temple menorah to the more than 700 appearances of the word “seven” in the Bible.

The four triangular courtyards in the corners of the chapels represent the four Gospels. And each of these three-sided courtyards obviously refers to the Trinity.

Within the octagon, arches form a circular corridor around the central space in which the sepulchre of the saint, the object of veneration, is assumed to have been kept. Christian symbols adorn the keystone of the arches.

Unfortunately, the only substantial remains of the octagon are the travertine supports of the central dome that originally covered it. The dome was made of wood covered in lead and measured 65 feet (20 m) in diameter.

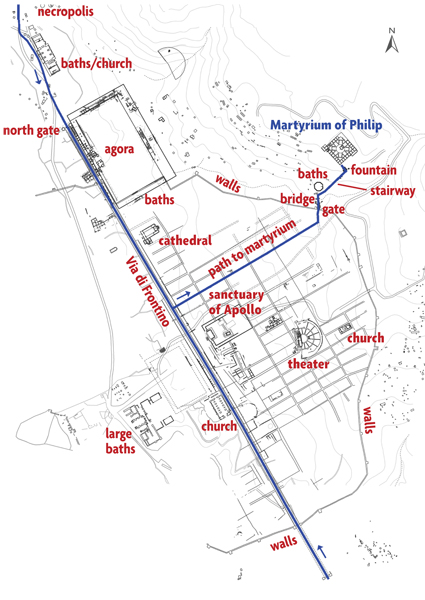

As impressive as the building is, equally impressive is the great processional road that led pilgrims to the hill northeast of the city on which the martyrium stood. The pilgrims would enter the city through the north gate in the fifth-century Byzantine fortification wall and then proceed down the recently excavated Via di Frontino, the main street of the city. After passing by the agora and then the cathedral, the path took a sharp left and headed east on another main street of the city. The path then left the city through a gate flanked by two towers and then across a bridge built over a stream.

044045

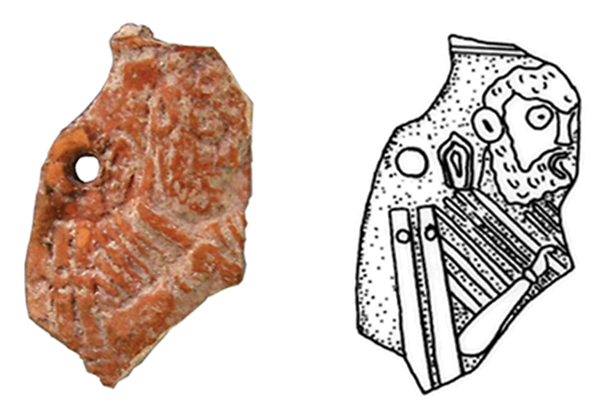

Immediately after the bridge stood a building whose octagonal plan recalls the architectural model of the martyrium. After excavation, it was possible to recognize this building as a bath. However, it was not possible to recognize it as such until completion of its excavation because it is a unique structure for a bath. It has no palaestra (gymnasium) for exercise or wrestling; its succession of spaces suggests individual baths where public nudity, typical of Roman baths, would have been impossible. The bath constituted an integral part of the pilgrims’ ritual journey and had a religious function; indeed in the channels of the building, in addition to the usual glass ampules and jars for unguents, were numerous terra-cotta eulogiae (small Christian mementos thought to confer blessings and memories of a holy visit). The eulogiae we found bore crosses and images of St. Philip.

It is not unusual to find a bathing facility in association with monasteries and pilgrimage sites, such as the monastery of St. Hilarion near Gaza and Kursi in Galilee.a The baths appear to be linked not only to hygenic needs but also to the pilgrims’ practices of purification before approaching the holy place.2 Such purification practices with water have roots in Jewish religious practice. Numerous Jewish ritual baths called mikva’ot from the turn of the era through the Byzantine period have been found in Israel. Qumran, the site adjacent to the caves where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, has several of these ritual baths. The Essenes, the Jewish sect often associated with Qumran and the scrolls, practiced daily bathing in cold water to purify themselves and promote sexual continence.

After a stop at the baths, pilgrims at Hierapolis continued their ascent via a 225-foot-long (70 m) travertine staircase 12 feet (3.5 m) wide. This flight of steps had a clear symbolic meaning: This was an ascent to the “Holy Mount.”

Along the way was a small terrace with a fountain on it where the pilgrims could slake their thirst.

After this they ascended the final flight of steps before reaching the gates of the sanctuary. This grand staircase of 40 steps is nearly 40 feet (12 m) wide.

As noted earlier, 28 small square rooms enclosed the octagonal martyrium. Here the pilgrims spent the night. The rooms had no flooring so the pilgrims slept in direct contact with the holy rock. The rooms were thus designed for incubation rites in which 046the saint appeared during sleep to announce his prophecies and heal the sick.

The pilgrims’ route concluded at the entrance to the great octagon where the tomb of the apostle Philip was venerated and the panegyric (an elaborate encomium, or praise, of the saint) was celebrated.

The memory of these traditions was kept alive even after the disastrous earthquake in the second half of the seventh century, which, accompanied by a fire, destroyed the entire complex. In the course of the ninth and tenth centuries, two small churches were built among the ruins of the building and some small cemeteries grew up around the ruins. Even after the Seljuk conquest in the 12th century, the place continued to be associated with the memory of the apostle and is mentioned by Western pilgrims who still came to venerate the site.

An extraordinary sixth-century illustration of St. Philip standing on the monumental staircase leading up to the martyrium can be seen—of all places—in Virginia: Richmond, to be precise, in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The museum’s collection includes a rare bronze bread stamp, no doubt found at Hierapolis. In 1965 the museum purchased the stamp from the well-known New York antiquities dealer Michel E. Abemayor, who died in 1978.3

Round and a little more than 4 inches in diameter, it features a full-length illustration of the saint, identified as Hagios Philippos (St. Philip) by a Greek inscription on either side of the halo around his head. He is dressed in a long tunic and mantle and stands on a set of monumental steps that leads up to two ecclesiastical structures on his right and left; each has a cross on top.

The building on the right is no doubt the martyrium, covered with a large dome. The other structure with its arched opening and lamps hanging inside is probably the ciborium or canopy over the tomb of the saint presumed to have been located in the central octagon of the martyrium.

Around the edge of the circular bread stamp is an inscription in Greek, the trishagion (the three holies) from Isaiah 6:3: “Holy, holy, holy, Lord of hosts; heaven and earth are full of Thy glory.” (This is still recited in the daily prayers in the synagogue, as well as a similar prayer in the Mass.)

On the back of this bread stamp is a ring handle to make it easier to impress the image on the stamp into the bread. Bread stamps were quite common in the Byzantine period, but few were as complicated as this one. Apparently, the pilgrims at the martyrium of St. Philip were given loaves of bread during the rites in honor of the saint. These eulogiae stamps gave the bread a spiritual power that conferred well-being on the recipient pilgrims.

The apostle Philip was hung on a tree upside down with irons in his heels and ankles in Hierapolis in Asia Minor.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1.

See Yizhar Hirschfeld, “Spirituality in the Desert: Judean Wilderness Monasteries,” BAR 21:05.

Endnotes

1.

The Italian Archaeological Mission to Hierapolis in Phrygia was founded by Prof. Paolo Verzone of the Politecnico of Turin; today, it is headed by Prof. Francesco D’Andria of the University of the Salento, Lecce.

Currently participating in the work are about 80 teachers, technicians and students from eight Italian Universities (University of the Salento, Politecnico of Turin, Catholic University of Milan, Cà Foscari University of Venice, Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa, “La Sapienza” University of Rome, “Federico II” University of Naples, University of Messina), the Italian National Research Council–Institute for Archaeological and Monumental Heritage (CNR-IBAM), and the University of Oslo (Norway).

The Mission’s official publications are published by Ege Yayınları (www.egeyayınları.com) [Istanbul].

2.

R. Elter, “Le complexe du bain du Monastère de Saint Hilarion à Umm El-’Amr, première synthèse architecturale,” Syria 85 (2008), pp. 129–144; Judith Sudilovsky, “Bathhouse Uncovered at Kursi. Early Pilgrimage Site Marks ‘Swine Miracle,’” BAR 29:01, p. 18.

3.

The stamp is published in Anna Gonosovà and Christine Kondoleon, eds., Art of Late Rome and Byzantium in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Art, 1994).