026

027

To the modern critical scholar, the Book of Jonah may be a romance, a short fictional delight with a moral. But that’s not what the author—whoever he or she was—intended. According to the author, our hero was an actual historical person, Jonah ben Amittai. Jonah not only has a named father but, as we learn in 2 Kings 14:25, he came from a particular place called Gath-hepher. According to the allotment of the tribes in Joshua 19:13, Gath-hepher is in Galilee.

Nobody really knows when the Book of Jonah was composed. That is with all due respect to my colleagues, both past and present. We are all guessing. Some say that the book is full of Aramaisms—phrases borrowed from Aramaic—and therefore late. On the other hand, my good friend and colleague George Landes says this is nonsense: If there are Aramaisms, they can be early as well as late; besides most of them are not Aramaisms anyway, but perfectly good Hebrew.

But it really doesn’t matter. The author intended us to regard Jonah as a prophet who lived in the eighth century B.C.E.a In the line of prophets, Jonah comes after Elijah and Elisha. He was a contemporary of Amos and Hosea. Jonah may even have been a student or protege of Elisha. According to rabbinic tradition,1 Jonah was the very child that Elisha restored to life. You will recall, from 2 Kings 4, that a woman of Shunem regularly fed Elisha when he passed her way and provided a place for him to rest. She was old and had no son. In gratitude, Elisha prophesied that she would bear a son. The prophecy came true. When the boy grew up, he got a severe headache and died. Elisha, however, restored him to life. This unnamed son was, according to the rabbis, Jonah.

So the main character in the book is intended to be a real person, someone who was important in the history of Israel in a particular time frame. Moreover, the political situation was intended to be realistic. It is no accident that the city of Nineveh is chosen as the place where Jonah is to prophecy. In the eighth century B.C.E., as earlier and later, Nineveh was the greatest city in the world.

Thus, there is an attempt to create verisimilitude, to invite you into a story with a framework of real people, real places and real events. It’s intended to be plausible. The reader is supposed to suspend disbelief and enter into the story as though it really were happening. Otherwise you miss the point. Otherwise, it doesn’t grip you as It’s suppose to.

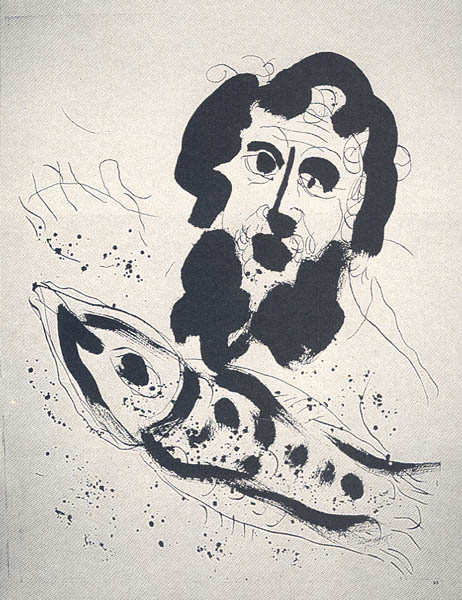

We all know that a chief element in the story is the big fish. It’s very important, first of all, because the author intends us to be alert. How do you attract attention? By having something unusual happen. This is a characteristic mode in the Bible. The function of miracles, for the most part, is to call attention to something else that’s going on that is even more important than the miracle. For example, take the burning bush—it burns but is not consumed (Exodus 3:2–5). When Moses sees the burning bush, he turns aside; God calls to him out of the bush and tells him that he is the God of his fathers and will rescue 028his people from Egyptian slavery (Exodus 3:6–10). You can argue endlessly about the meaning of the burning bush, but its function in the story is to attract the attention of the reader and of Moses, who was presumably preoccupied with his cattle and sheep. It is sufficiently provocative so that Moses stops and turns aside to see what is going on—and so does the reader. And the story of Israel begins that way. If there were no burning bush, who knows what would have happened? The same can be said of the fish in the Book of Jonah. Without the fish, it would be just a story. Even Jonah realizes the fish is important. And we are supposed to, as well.

The story begins with God addressing Jonah, instructing him to go and make a proclamation to the city of Nineveh. Simply using Jonah’s name — “the word of the Lord came to Jonah the son of Amittai”— suggests that this is not the first time Jonah was called; this is not the beginning of his career. He was already established as a prophet. That may be going beyond the evidence, but that’s the impression the text gives; as soon as the name is given, you get the idea this is a well-known prophet.

Jonah’s response to God’s call is presented in unique fashion. While it is contrary to fact, the author gives the impression that Jonah simply gets up and departs.b Not only so, but he heads in the opposite direction from Nineveh. The author doesn’t have to say it; Nineveh and Joppa are in opposite directions. But the author does explain that when Jonah expostulated with God about the assignment, he received no satisfactory answer, decided nothing was to be gained by further debate and just ran off.

This is unheard of and, of course, unforgivable. This is a clear violation of a prophet’s primary obligation. The obligation of a prophet, very simply stated, is unquestioning obedience. The classic statement is in Jeremiah 1:4–10 where God explains to Jeremiah, who has just raised the question: “To all to whom I send you, you shall go; and whatever I command you, you shall speak.” In more colloquial language: 029“You go wherever I tell you, and you say whatever I command you.” That’s all. That’s all a prophet has to do, but he must do that. No alternatives. That’s what a prophet is supposed to do. And Jonah is clearly not doing it.

The turning point of the story, as far as Jonah is concerned, is the casting of the lots. When the lots are cast on the ship to find out who is responsible for the terrible storm, Jonah is identified. Whatever the sailors may think, Jonah knows that God has caught up with him. What was in his mind before this is hard to figure out. Jonah was probably familiar with Psalm 139 (“O Lord … you know when I sit down and when I rise up; you discern my thoughts from afar … where shall I flee from thy presence? … If I … dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there thy hand shall lead me”). Jonah no doubt knew that you really can’t escape God. He knew that, but probably figured that if he could slip away for a while, God would try someone else, or, when he ultimately found Jonah, by that time either the commission would lapse or somebody else would have done it—and that’s all Jonah wanted. But with the casting of lots, Jonah realizes that that’s not to be. From that point on, Jonah is fully cooperative.

Now a lot of nasty things have been said about Jonah’s ethnocentrism. Supposedly, he didn’t like gentiles; that’s why he didn’t want to go to Nineveh: The gentiles might be saved. Based on this ethnocentric supposition we are told that the Book of Jonah was written as a Criticism of this narrow parochialism, to encourage the tolerant, universalist attitude that we should all have. I don’t think that’s really the point at all.

For one thing, it’s very unfair to Jonah. Not only is he thoroughly decent and polite to the sailors—all gentiles—on the ship with him, he goes out of his way at great personal risk to save their lives: He has himself thrown overboard. This is not the act of someone who is narrow-minded about his fellow human beings.

The real issue is something else. Jonah had some very fixed ideas about God; that’s where the quarrel really is. That he didn’t want to go to Nineveh has nothing to do with the fact that the Ninevites were gentiles.

Jonah’s problem was with a new eighth-century B.C.E. doctrine about God. It is the doctrine of “the God who repents about the evil” (niham ‘al hara ‘a)2 he says he’s going to do that concerns Jonah. This is the doctrine of the eighth century. Previously there had to be punishment or retribution for wrong doing. The new idea was that repentance is equivalent to, or has equal value with, punishment or retribution. In short, you can substitute repentance for retribution—and come out even. When I first discovered this, it startled me, but I couldn’t find this idea in earlier materials. In these older traditions, we find different views about who escapes and who gets punished; we find different views about what motivates God. But what runs through it all is: You get what you deserve. That’s the bottom line. That’s true not only in the Hebrew Bible, but it’s also the major thrust of the New Testament. In the end, everyone must stand up to judgment.

The notion that human repentance will produce equal divine repentance and that things will then be evened out and you can start all over again is not found before eighth century B.C.E. Consider, by way of contrast, the case of Sodom and Gomorrah. The people are wicked. God and Abraham debate about how to handle this situation (Genesis 18:22–33). There isn’t even a hint that if these people will only repent, things will work out differently. The only question is, how many righteous people must be in the city in order for the city to be spared? Can the righteousness of the righteous somehow cover for the iniquity of the iniquitous? To some extent, 030God agrees. But that idea has nothing to do with repentance. Or again, Moses intercedes with God when the people worship the golden calf. How is it reasoned out? Moses intercedes and actually tells God to repentc (Exodus 32:12). But then Moses proposes this idea: He says, “If you are agreeable, forgive them. But if not, then wipe me out of your book.” God and Moses keep trying to make a deal. God’s first response is, the book of rules is my business, not yours. Second, you do your job; I’ll do mine, which is to pick out the sinners and give them their due. Now, I admit this is a paraphrase, but it is essentially accurate. If you don’t believe me, look up the original in Exodus 32:30–34.

Thus, the notion that human repentance will produce corresponding divine repentance and an actual clearing of the slate is a new idea. In Israel’s classic credo (Exodus 34:6–7, containing the 13 attributes of God, later spelled out by the medieval Jewish commentator Maimonides), repentance is not listed. True, the credo begins with “the gracious and compassionate God” (‘el rahum we-hannun); it also goes on to say that God forgives iniquity, transgression and sin. But then we find the exact opposite: he “will by no means acquit the guilty” (Exodus 34:7). There may be a contradiction here—or at least a paradox—but no one tries to resolve it in terms of reciprocal repentance.

The Book of Jonah is designed to explain and to support this new view of reciprocal repentance: If you repent, God will repent; it doesn’t matter who: Repentance is open to everyone, even the Ninevites. If they repent, they have as much right to God’s repentance as anyone else. Jonah does not accept this. He is emotionally, psychologically and theologically opposed. It’s a particular problem for him, because the doctrine is being propounded not by a fellow theologian, but by God Himself. What is he to do? That’s why he runs away. There is nobody to appeal to.

When Jonah realizes that the game is up, he tells the sailors, “Pitch me into the sea and you will be saved.” This shows that Jonah was not biased against gentiles; on the contrary, he was concerned about their well-being. More than this—he believes in justice, equity, in a word, fairness: The sailors are innocent; they have no part in this disagreement between Jonah and God; therefore it is not right for God to threaten them simply because God is trying to get Jonah. So Jonah makes it easier for everyone; he tells the sailors to throw him overboard.

When the fish vomits Jonah back onto dry land, God tells him, “Now go on to Nineveh,” and he does, immediately, because he realizes there is no escape. He goes to Nineveh and gives the message: “Forty days and Nineveh shall be destroyed.” At this point, the situation of the Ninevites is just like that of the people of Sodom and Gomorrah. But then comes the greatest miracle of all. All of the Ninevites repent: First the people, then the king and finally even the cattle. I don’t think that’s meant as a joke. The cattle repent because they are dressed in sackcloth and ashes, just like the people.

What led the Ninevites to believe this stranger—and therefore to repent? I believe it was the miracle of the fish. Now we begin to see why the fish is so important, so critical to the story. When the lot falls on Jonah, the sailors ask him all about himself and he proceeds to tell them (Jonah 1:8–9). I believe he told them the whole story of his predicament. And I think the news preceded Jonah to Nineveh. Can you imagine if you heard that a man was coming, one who had spent three days and three nights in the belly of a fish, and that he had a message to deliver—wouldn’t you go to hear him? Who wouldn’t pay attention to his words? Even I would go to listen!

The irony is that if Jonah had followed his original instruction, his message would probably have failed, and he would have been happy. If he came as a stranger and simply announced that in 40 days the city would be destroyed, he would have been ignored. (The lesson for Jonah: Obedience is the best policy.) But if a man who has just returned from three days and three nights in the belly of a fish comes and says “In forty days Nineveh will be overthrown,” then he commands attention: What would you do in this situation? I would confess to and repent for everything. And that is just what happened. The Whole city repented—and was spared. And then God also repented: “God repented of the evil which he had said he would do to them; and he did not do it” (Jonah 3:10).

A bitter argument then ensues between God and Jonah. “I knew all along this is the kind of a God you are,” Jonah says. Then he repeats the credo from Exodus 34:6–7—but with a difference: “I know you are a gracious and merciful God, slow to anger and abounding in steadfastness” (Jonah 4:2). But, instead of going on, as does Exodus 34:6–7, to say that God will by no means clear the guilty, Jonah substitutes instead a description of God as one who “repents of evil” (Jonah 4:2). In short, Jonah is saying, “I knew from the beginning what was going to happen; that’s why I ram away.” If people repent, God will repent—and that’s what happened.

For Jonah, the outcome was all wrong, although Jonah has to admit that what happened was according to the new rule. My suspicion is that Jonah’s sense of justice was offended. He would have said there are some things that you just cannot forgive. 031Polls of the American public confirm that they too hold this view, that deep down inside, human beings do not accept the real teaching of the Bible, Old or New Testament. They feel repentance is too easy, too cheap, and that even if people repent, God should be a little more careful, because with a net like that, a lot of people will slip through who shouldn’t. So too Jonah. He’s unhappy about it, and he says so. But he can’t fight it. It happened according to the rules: The Ninevites were given a chance to repent and they did, so God changed his mind.

But that is not the end of the book. We have another miracle, just as important as the big fish, namely the qiqayon which is generally translated “gourd,” but is really just a big bush. God makes it grow up over Jonah to shade him from the sun and its heat. Then God plays a dirty trick on Jonah. The next day, God sends a worm or parasite that chews up the roots, and the bush dies. Jonah is absolutely out of his mind with grief and rage. He is ready to die. He says so (Jonah 4:6–9). But what is this latest demonstration of divine power all about?

After Jonah says he is so angry he is ready to die, God replies very briefly—a mere two verses—and with that the book ends. “You’re sorry for the plant,” God says. “You didn’t labor for it, you didn’t make it grow; it is a child of the night and perished in a night” (Jonah 4:10). In short, God says, “the plant has no significant value, yet you, Jonah, are ready to die about it. If you had the power, Jonah, you would surely have spared the plant. How do you think I feel?” God asks: “Should I not feel sorry for Nineveh that great city of more than 120,000 people who do not know their right hand from their left?” (Jonah 4:11).

Well, it’s a pretty farfetched comparison, but look at the content more closely. Notice that God says nothing about repentance. He doesn’t justify his saving the Ninevites on the ground that they repented.

Instead, God says they don’t know their right hand from their left hand. The common view among scholars is that they are morally obtuse (cf. Ecclesiastes 10:2). The idea is that until a certain age, moral ignorance is assumed. Little children don’t know the difference, just as they don’t know the difference, between their right hand and their left hand. Therefore they are not morally responsible.

Even after everything that has happened, including their repentance, God says the Ninevites don’t know their right hand from their left. He thereby confirms what Jonah was saying, namely that you can’t trust their repentance. But God in effect says, so what? I pitied them, I felt sorry for them and that is what truly counts, just as you pitied the gourd.

God is telling Jonah that that is what’s behind the whole thing—pity, compassion for his children. This whole repentance business was just a charade. That was for Jonah’s benefit, to give Jonah some anchor to hold onto, to say, well, you know, they did repent, so Jonah has to say, yes, that’s right, God acted according to the rules, even if this repentance business is a new one. But God is now saying that regardless of the repentance, he would have saved them. “They’re human beings,” God is saying. “Don’t I have the right to be sorry for these people who don’t know their right hand from their left? And if I’m sorry for them, they’re not going to be destroyed.”

There is no answer from Jonah! I think he must have been shocked out of his mind!

To the modern critical scholar, the Book of Jonah may be a romance, a short fictional delight with a moral. But that’s not what the author—whoever he or she was—intended. According to the author, our hero was an actual historical person, Jonah ben Amittai. Jonah not only has a named father but, as we learn in 2 Kings 14:25, he came from a particular place called Gath-hepher. According to the allotment of the tribes in Joshua 19:13, Gath-hepher is in Galilee. Nobody really knows when the Book of Jonah was composed. That is with all due respect to […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

B.C.E. (Before the common Era) and C.E. (Common Era) are the scholarly alternate designations corresponding to B.C. and A.D.

In fact, as we learn later, in Jonah 4:2, Jonah did in fact argue; he there says to the Lord: “O Lord: Is this not what I said when I was still in my own country? That is why I fled beforehand to Tarshish.”

See my earlier article, “Who Asks (or Tells) God to Repent?” BR 01:04.