Flora of the Shroud of Turin

Avinoam Danin, Alan D. Whanger, Uri Baruch and Mary Whanger

(St. Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden Press, 1999) 52 pp., 25 b&w photos, $14.95

Is the Shroud of Turin the linen cloth that covered the body of Jesus after he was crucified? That is the question—and it is one that has plagued devoted Christians and scientists for centuries.

Late last year a book published by the prestigious Missouri Botanical Gardens became the newest entry into the controversy surrounding the authenticity of the shroud. Flora of the Shroud of Turin focuses on evidence of floral remains on the shroud and explains why its four authors believe these remains confirm that the shroud dates to before the eighth century A.D. They claim that pollen and images of flowers on the shroud suggest that the shroud came from the vicinity of Jerusalem and that it was first used during the months of March and April (that is, around Easter). The authors are Avinoam Danin, a professor of botany at Hebrew University, Jerusalem; Uri Baruch, a palynologist (one who studies pollen) with the Israel Antiquities Authority; Alan Whanger, a retired member of the Duke University Medical Center and founder of the Council for the Study of the Shroud of Turin; and Mary Whanger, Alan’s wife and coauthor, with him, of The Shroud of Turin: An Adventure of Discovery.1

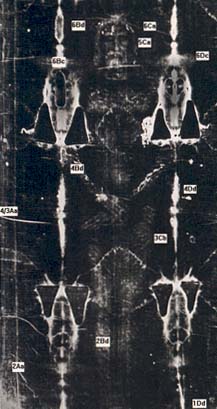

For those who are not familiar with the Shroud of Turin (but who isn’t?), a bit of background information may be helpful. The shroud, which is purported to have been the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth, shows full-length front and back images of what appears to be a crucified man. It is made of fine linen and is 3.5 feet wide and a little over 14 feet long. The history that some associate with the Shroud of Turin begins with the writings of Eusebius, an early Christian historian.

Eusebius reports that in 30 A.D. a certain Thaddeus, one of Jesus’ disciples, gave “a cloth with an image on it” to King Abgar V, whose palace was in Edessa (in modern Turkey). Abgar was severely ill with what scholars now believe may have been leprosy. However, after Abgar touched the cloth, he was miraculously healed. The news of his cure spread rapidly, and soon many pilgrims were flocking to Edessa to see and touch the cloth. More than 900 years later, in 944, the emperor of the Byzantine Empire, Romanus I, wanted to obtain the “magic” cloth, which by then had become known as the Mandylion, or “Little Handkerchief.” The city of Edessa refused to give up its sacred relic, so Romanus I laid siege to the city until the people surrendered the Mandylion. The cloth was then taken to the Byzantine capital of Constantinople.

According to Byzantine historians, the Mandylion bore only the facial image of Jesus. Some believers today say that the Mandylion was the shroud, folded into eighths to make a small square, leaving only the face visible. (This may be why—if the Mandylion and the shroud are one and the same—historians did not record that the Mandylion contained a full-body image. But why they wouldn’t realize its true size is hard to fathom.) In 1204 Knights of the Temple of Solomon (an order of monk-knights, also known as the Knights Templar) of the Fourth Crusade reportedly took the cloth—whether the Mandylion or the shroud—to France. It remained in France until sometime during the early 1300s, when it was removed to England for safekeeping after King Philip IV of France destroyed and confiscated properties owned by the Knights of the Temple of Solomon. After about half a century in England, it returned to France, and in 1357 a French nobleman, Geoffrey de Charmy, displayed a cloth to the public in Lirey, France, as the “true burial shroud of Jesus.” However, he never revealed where the shroud came from nor how he acquired it. This is the first verifiable reference to the object now called the Shroud of Turin. In 1453 that cloth was given to the King of Savoy. For more than a century, it remained in a castle belonging to the House of Savoy in Chambéry, France. After surviving a fire in the castle in 1532, the shroud was eventually brought to Turin, where it has remained since 1578, in the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist.a

Almost from the first appearance of the cloth, questions were raised about its authenticity. Many aspects of the shroud make it a challenging religious icon to examine and attempt to validate. Add the element of religious faith to the numerous careful scientific studies of the shroud, and immediately problems develop. Some believe the shroud is authentic and view any attempt to cast doubt on its origin as blasphemy, the work of Satan or of nonbelievers who will do anything to destroy or challenge Christian faith. During the past four decades, whenever a specialist has attempted to use scientific or forensic techniques to examine the shroud, any affirmative results have been immediately accepted by many of the faithful, while any negative results have been met with immediate skepticism by those same faithful, who then question the accuracy and technical validity of the scientific methods used. For example, during the 1980s small portions of the shroud were removed and sent to various laboratories for radiocarbon dating. Laboratories at Oxford University dated the shroud fragments to 1322 A.D. ± 50 years; the University of California at Berkeley dated them to 1340 A.D. ± 50 years; and the University of Arizona and the Zurich Institute for Middle Energy Physics dated the fragments to an average of 1325 A.D. ± 65 years. These dates were immediately challenged by the faithful, who argued that (1) the tested fragments were pieces of linen used to repair the shroud during the 1300s, or (2) recent bacteria and fungi inside the examined fibers yielded a date later than the actual date of the shroud, or (3) the heat of the 1532 fire (which scorched the shroud but did not burn it) may have increased the carbon 14 content of the linen and thus produced a misleading date. (The Vatican, however, which became the shroud’s owner in 1983, never challenged the carbon 14 dating results.)

Neither the radiocarbon dating nor the many other scientific tests performed on the shroud are the focus of The Flora of the Shroud of Turin or, therefore, of this article.b Instead, I shall focus on the subject of the book: the botanical evidence associated with the shroud.

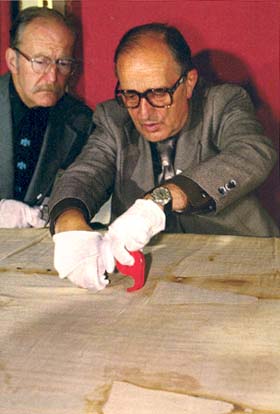

The botanical investigation of the shroud began in late 1973, when Max Frei, director of the Zurich Police Scientific Laboratory, was allowed to make 12 “sticky tape pulls” from the shroud. A sticky tape pull is made simply by placing clear adhesive tape on a surface and then pulling it back to see what it may have collected. Using this method, Frei claimed he gathered several hundred pollen grains from the shroud.c He first reported his findings during a lecture at the 1978 Congress of Turin; these findings are recounted in Walter McCrone’s Judgment Day for the Shroud of Turin. According to McCrone, a shroud specialist, “At first glance, Frei’s results seem to make an unassailable case for the shroud’s having been in Palestine and Turkey.”

McCrone reports that Frei found 49 pollen types on the shroud, 34 of which Frei claimed came from plants that grow only in Israel and Turkey. McCrone also relates that at a second lecture in Turin, in 1981, Frei stated that a reexamination of the pollen on the original 1973 tapes and an examination of an additional 26 sticky tape samples taken in 1978 revealed, not 34, but 54 different types of pollen that could be traced to plants found exclusively in areas of Palestine and Turkey.2 In any case, Frei never clearly explained in convincing detail how he made these crucial pollen identifications, nor is it explained in the book under review. Frei died in 1983, so we may never know.

The authors of Flora of the Shroud of Turin report slightly different numbers for the various pollen types, but the difference is not significant. (For example, they claim that Frei identified 47, rather than 49, pollen types in 1973.) I do not know which report is accurate because I do not have access to all of the original German and Italian notes, manuscripts and obscure publications attributed to Frei (referred to in the McCrone book and also cited in the book under review). In one of Frei’s own reports, he says that he identified 48 (not 47 or 49) pollen types from the sticky tapes.3

Uri Baruch, one of the authors of the current book, reexamined the sticky tape samples, slides and other materials collected by Frei in 1973 and 1978 (which Max Frei’s widow made available to the Association for Scientists and Scholars International for the Shroud of Turin in 1987). However, I can find no mention in this book nor in any other published article or personal letter indicating how the evidence collected by Frei was stored and if the evidence was protected from contamination between the time of its collection, during the 1970s, and the most recent reexaminations of it in the late 1990s.d

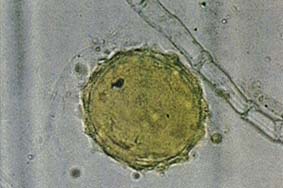

In an effort to confirm the pollen types reportedly found by Frei on his two sets of sticky tape samples (1973 and 1978), Baruch compared those pollen samples with modern pollen collected in Israel. Baruch identified 37 pollen types on the shroud that are only found in Israel and Turkey (whereas Frei had claimed 54). Of the 1973 samples, Baruch notes that “because of the sticky tape covering [cellophane and glue] and of heavy deterioration of the [pollen] grains,” he was able to confirm only 16 pollen types (Frei identified 47 or 49, depending on the source). Baruch also states that he was not willing to confirm identification beyond the genus level for most of those 16 types because the “poor optical quality of most samples (caused by the covering sticky tapes) and pollen grain deterioration prevented in many cases positive identification of the grains and in many other cases did not permit determination beyond the most basic level (usually the family level).” Baruch found that the 1973 and 1978 sticky tapes contained 313 individual pollen grains. He says he could make a “positive identification” on 204; of those, he says that 91 (44.6%) were Gundelia tournefortii.

Regardless of the actual number of different pollen types, the important issue is whether or not pollen alone can be used to verify that the shroud was ever in the region of Jerusalem.e The authors of Flora of the Shroud of Turin partially base their claim that the shroud came from the region of Jerusalem on those data. They write, “The two plant species identified as part of the shroud, beyond any reasonable doubt, are Gundelia tournefortii [a plant distantly related to sunflowers and native to the steppes and rocky areas of the Near East] and Zygophyllum dumosum [a plant found in the desert around the Dead Sea]. Their presence on the shroud, with the former confirmed by its pollen grains and both identified by presumed imaging, indicate[s] that the shroud originated in the spring season (March-April) in the Jerusalem area.” But even if the evidence of these two plants can be linked to the shroud, the known geographical range of Gundelia tournefortii covers most of the Middle East and large regions of Iraq, Iran and Turkey.

In addition to the pollen data, the authors also rely on other floral evidence to authenticate the shroud. They write that more than 100 images of flowers, leaves, seeds and stems are observable on the shroud, although they admit that “plant images are rather difficult to see directly on the shroud.” The authors tell us that “photographically enhanced photos [of the shroud] from negatives made by [Guiseppe] Enrie in 1931 are excellent tools for discovering plant images on the shroud.” However, the authors also admit that “second- and third-generation prints of his [Enrie’s] negatives have been the source of almost all of the photographs used in the research reported in this paper [book].” The authors identify 14 plant types from photos of the shroud. Most of the plant images, they note, are distinct enough in enhanced photos for the plants to be identified to the level of both genus and species. Some of the plant images they identify are Chrysanthemum cf. coronarium L., Pistacia atlantica Desf., Pistacia lentiscus L., Zygophyllum dumosum Boiss—and Gundelia tournefortii L. The authors note that Chrysanthemum coronarium, one of the most prominent plants seen in the shroud images, is a widespread Mediterranean species and therefore “is not a conclusive geographical indicator for the shroud.” Of Gundelia tournefortii, however, they say that this pollen “may serve as an indicator plant for the entire assemblage … Its phenology [the relationship of plant to climate] is also indicative for chronology of the Shroud; Gundelia tournefortii blooms in Israel between March and May,” the period during which Easter falls.

Finally, the authors attempt to seal their claim for the shroud’s authenticity by saying that an image of a “bouquet [of flowers] containing Zygophyllum dumosum appears on the body image’s upper chest. Here, two young but well-developed succulent leaves are visualized … The only species of Zygophyllum in Israel and its neighboring countries that sheds its pair of leaflets annually is Z. dumosum.” According to a map provided in the book, the plant only grows in a very small region that includes part of the Sinai Desert and a narrow band around the Dead Sea in western Jordan and eastern Israel.

As a botanist, I have been trained to be skeptical. As a palynologist, I am especially skeptical of pollen data that are not derived from multispecies comparisons. That is why I am not convinced by the pollen evidence reported in Flora of the Shroud of Turin.

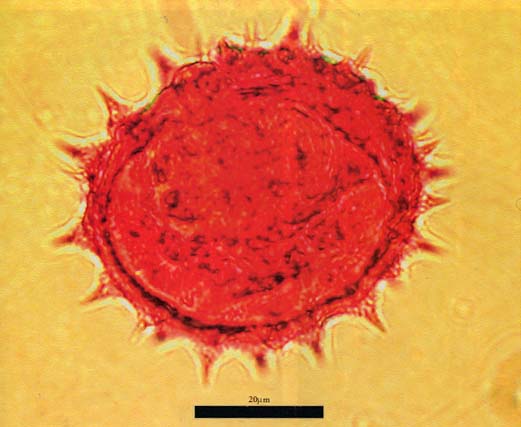

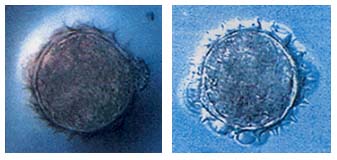

I do not believe current pollen studies can be used to authenticate the shroud. The authors base their precise identifications of the Frei pollen (in some cases even to the species level) on techniques that utilize only light microscopy. And they note that throughout most of their study, they could not cover the slides in immersion oil (which makes it easier to view the grains) for fear that it might damage the sticky tapes. Only one late sample, examined at 1000× magnification, was studied using immersion oil. I believe pollen experts would agree that to identify most pollen to the species level, one cannot rely on the optical resolution provided by light microscopy (especially at magnification levels less than 1000×), which has a resolution level no greater than .27 microns (10,000 microns = 1 millimeter). For most pollen types, species can only be separated and identified when resolution levels reach a precision of greater than 0.05 microns. These levels of resolution are only possible when using either SEM (scanning electron microscope) or TEM (transmission electron microscope) equipment.f

The authors base their pollen identifications on their examination of the pollen trapped on the sticky tape samples collected by Frei in 1973 and 1978. I have spent more than 30 years in pollen research and in the teaching and training of graduate students. For over a decade I have been conducting forensic pollen studies for federal, state and private agencies both in the United States and abroad. I have sometimes used sticky tape pulls to collect surface pollen and dust from a crime scene, and I have found that making precise pollen identifications from such sticky tapes is often problematic at best. When pollen matures on the anthers of flowers, especially those from insect-pollinated plants (such as Gundelia tournefortii), the individual pollen grains often have layers of oils and waxes on their surface designed to stick to the legs and hairs of visiting insects. These oils and waxes serve the pollination process well by keeping the pollen attached to the insects, but they often obscure the critical surface features on pollen grains that are needed for precise and accurate identification. Further, fresh pollen grains are full of cytoplasm containing various fluids, proteins, starches, oils and DNA material needed for reproduction. Unless these contents are removed chemically, studying the detailed structure of the pollen grain wall (called the exine) is often impossible. The authors write that Baruch used the acetolysis method (a mixture of sulfuric acid and acetic anhydride used to dissolve and remove surface waxes, oils and the grain’s cytoplasm) to prepare comparative pollen slides for reference, because it “permits better visualization of exine details.” But, although used on the control pollen, the acetolysis method was not used on Frei’s samples from the shroud. In most cases, without studying the detailed surface structure and the pollen wall, we simply cannot make a precise identification of the pollen to the genus, much less the species, level.

But even more important, when pollen remains on sticky tape for a long time, the individual grains begin to sink into the tape’s glue. Depending on the size and surface ornamentation of the pollen, part or most of the grain may sink to a point where the surrounding glue obscures essential morphological features. (The authors have noted that this was a major problem during the study.)

All this makes me very skeptical that anyone can positively identify all of the pollen the authors claim to have identified from sticky tape samples taken more than 20 years ago.

Much of the authors’ case for authenticity rests on the precise identification of pollen from a single species, Gundelia tournefortii L. That plant is only one of over 920 different plant genera and only one of over 19,000 separate species found in the large plant family Asteraceae (composites).g Even though more than 95% of all the pollen produced by plant species in this family looks nearly identical using only the optical resolution of a light microscope, a few of them do produce pollen that can be separated to the genus level. However, I estimate that without extensive multispecies studies, no more than a dozen of the pollen types in this family can be identified easily to the species level, even using the highest levels of optical resolution possible with a light microscope. At this point I am not willing to include Gundelia tournefortii pollen in that small fraction of unique types.

I have looked at the pollen from many composite species, including Gundelia tournefortii. If pollen believed to be Gundelia tournefortii were associated with critical evidence in a forensic case, I would not be willing to testify that I could confidently separate it from all other composites, especially if I were only using a light microscope. If the authors can do this, and can identify this pollen taxon to the species level, as they claim in this book, then they should provide convincing evidence and list the criteria they used. I would expect, for example, SEM and TEM studies and multispecies comparisons. They have not done so.

The authors correctly state that Gundelia tournefortii is a monotypic genus (meaning that the genus Gundelia is represented by only one species, G. tournefortii) in this large family of composites. They go on to say that “for the Near East, its [Gundelia’s] pollen morphology is unique for the family and for the entire flora.”

I have conducted field research and pollen studies in Israel, and I have examined pollen samples collected in Turkey. I know other pollen scientists who have also examined pollen samples from sediments in Israel and other regions of the Near East. Like me, many of them consider the claim made in this book about Gundelia pollen to be unproven. It is possible these authors might be correct in their assumption that the pollen of Gundelia is truly unique. Nevertheless, I do not believe the authors of Flora of the Shroud of Turind have looked at all of the Asteraceae pollen types nor all of the other possible pollen types that occur in the natural flora in the Near East. Until they do, I wonder how they can be so certain of their precise identification.

In addition to the pollen samples, there are the more than 100 plant images purportedly found on the shroud (and only visible in enhanced photographs made from negatives dating to 1931 and 1978). These are supposed to be the images of flowers and plants that were placed on or in the shroud as grave offerings at the time of Jesus’ death. Most of the 14 different plants that the authors claim can be identified from these faint images are identified to both the genus and species level. But the only evidence the authors provide consists of some faint black-and-white pictures. A couple of the images are impressive; most are not. My lack of training in photographic processes makes me ill equipped to judge the reliability of the process by which these plant images appeared after the pictures were enhanced from the original 1931 and 1978 negatives. Nevertheless, I know that there are many new photographic techniques and that there are a variety of new ways to digitally enhance faint images. I wonder why those newer techniques were, apparently, never used; if they were, the authors make no mention of them.

So where does this leave the controversy over the Shroud of Turin? I suspect that not much has changed. Those who believe in its authenticity as a matter of faith will be happy to learn that this new book claims to confirm what they have always believed. Those who have expressed disbelief about the age of, and purpose attributed to, the shroud will not have their doubts allayed.h

I believe that if the world’s scientists were to read this book, many of them would never be convinced of the validity of any of the existing pollen data of the shroud because the book fails to offer clear explanations as to 1) exactly how the tape samples were collected; 2) how the tapes and other pollen evidence were stored during the last 20 years; 3) what happened to the pollen that was purportedly removed from the original set of 1973 tapes; and 4) how these authors can be so sure of their pollen findings while most other scientists remain unconvinced. Until new pollen samples can be collected from the shroud, under sterile conditions, using modern techniques (as were used to study the Gondar hanging), I—and most other serious scientists—will remain unconvinced.

As a final comment, I would like to mention that rarely have I found such total disagreement among so many people over the possible authenticity of an object. And rarely have I seen so many try to cast so much doubt on the character and professional integrity of others working on a project.

After my first reading of Flora of the Shroud of Turin, I had too many unanswered questions to write a competent review. So I read several books about the shroud.4 I also contacted a scientist who has worked on scientific aspects related to the debate over the shroud for more than 30 years. Finally, I read a number of articles, notes and personal letters that were written about the shroud. After all of my research, I remain skeptical.

One thing is certain: The controversy regarding the Shroud of Turin is far from resolved. There is much room for more research and more books on this topic, which continues to capture the interest and fascination of so many people.

Is Flora of the Shroud of Turin worth the purchase price? I suspect that it is. If you are one of the faithful and are interested in the controversy that surrounds the Shroud of Turin, you will want to own this book. If you are a pollen scientist, you might want a copy of the book to use as an example of how many problems can develop when pollen data are collected and then used to illuminate past events and define geographical locations. If you are a skeptic, however, it is unlikely that this book will appeal to you, nor will it convince you of the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

In 1694 a chapel was built next to the Cathedral and the shroud was moved there. For a more detailed history of the shroud, see Robert A. Wild, “The Shroud of Turin: Probably the Work of a 14th-Century Artist or Forger,” BAR 10:02.

On the dating, see Suzanne F. Singer, “Has the Shroud of Turin Been Dated—Finally?” Bible Review, April 1989. For more on other scientific examinations, see Joseph A. Kohlbeck and Eugenia L. Nitowski, “New Evidence May Explain Image on Shroud of Turin,” BAR 12:04; and Wendy Miller,

Frei does not mention the brand of tape he used, but another author reported that Frei used clear Scotch tape. I have performed numerous tests using Scotch tape and have never been able to completely clear the adhesive from the pollen.

One of the authors of this book, Alan Whanger, does mention in another publication that “the sticky tape slides were sealed in her [Mrs. Frei’s] presence for transportation back to the United States” (Whanger, “Pollens on the Shroud: A Study in Deception,” Shroud News 97 [1996], pp. 11–18). But I wonder what is meant by “sealed,” and I also wonder why there is no mention of what happened to all of the other pollen evidence that Frei reportedly examined.

See Robert A. Wild, “The Shroud of Turin,” BAR 10:02, who cites Frei’s work and writes, “The presence of pollen from native Palestinian plants does not prove that the shroud itself was ever in Palestine, much less that it originated there.”

While light microscopy simply uses a lens to bend waves of light, electron microscopy uses electromagnets to bend beams of electrons, allowing much greater resolution.

The taxa for the Gundelia tournefortii pollen are as follows: Kingdom = Plantae, Division = Tracheophyta, Subdivision = Spermatophytina, Class = Angiospermae, Subclass = Dicotyledoneae, Order = Asterales, Family = Asteraceae, Genus = Gundelia, Species = tournefortii. The family Asteraceae is commonly known as the sunflower family; Gundelia is therefore closely related to those familiar flowers. An everyday rose, such as the brier rose (Rosa canina), for example, follows the same taxonomic classifications as tournefortii until order, when it splits off into Order = Rosales, Family = Rosaceae, Genus = Rosa, Species = canina.

Believers and nonbelievers alike should read the relevant discussions in Gary Vikan, “Debunking the Shroud: Made by Human Hands,” and Walter McCrone, “The Shroud Painting Explained,” BAR 24:06.

Endnotes

Mary Whanger and Alan Whanger, The Shroud of Turin: An Adventure of Discovery (Franklin, TN: Providence House, 1998).

Max Frei-Sulzer, “Wissenschaftliche Probleme um das Grabtuch von Turin,” Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau 32:4 (1979), pp. 133–135.

Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes, The DNA of God?: The True Story of the Scientist Who Reestablished the Case for the Authenticity of the Shroud of Turin and Discovered Its Incredible Secrets (New York: Doubleday, 1999); Gilbert R. Lavoie, Unlocking the Secrets of the Shroud (Allen, TX: Thomas More, 1998); McCrone, Judgment Day.