How Job Fulfills God’s Word to Cain

040

041

Ronald S. Hendel’s article, “When God Acts Immorally—Is the Bible a Good Book?” BR 07:03, obviously touched a raw nerve. In examining the story of Cain, Hendel suggested that God may not be a perfect God, but a good God nevertheless, and that the Bible may not be a wholly good book, but a “good enough” book. Judging from the outpouring of letters that followed, many readers took exception—even offense—at Hendel’s reading of the story.a

Without going over the same ground as Hendel and the subsequent letter writers, it might be fruitful to review the story of Cain and his seemingly unfair punishment. In the process, I hope to offer some new insights by comparing two biblical figures who are not usually thought of as linked—Cain and Job.

In our evaluations of characters in the Bible, we naturally list Cain with the villains and Job with the heroes. We decry the inherent evil of Cain and applaud the innate goodness and faith of Job. We see Cain’s murder of his brother Abel as the first and ultimately the worst human injustice, so different from the quietness and patience of Job, whose righteousness remains firm despite inhuman pain and grief.

But if we look closer, Cain and Job are very similar. They are both simple men, trapped in the role of tragic hero. Not of their own doing or through any initial fault of their own, their lives become increasingly manipulated by forces beyond their control. What differentiates them is how they respond to circumstances directed from above. They are asked to “play by the rules,” though those rules are not fair; they look for justice and mercy, but find neither.

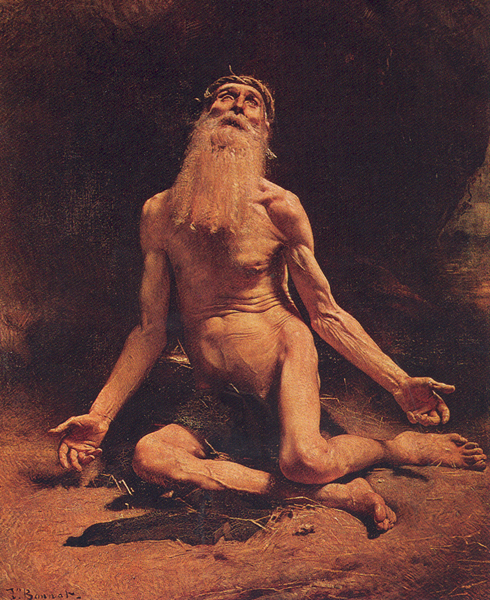

In literature, the tragic hero is caught in a net of disturbing circumstances, a web spun by others, that only tightens as the hero struggles against it. Human frailties and weaknesses work against good intentions, and as we watch from a distance, we know only too well how the story has to end. The tragic hero has the sympathy of the observer for he is fated to be defeated, and we are saddened to see that his own character faults prevent him from knowing it. It is not difficult to see Job as tragic hero. It is with the character of Cain that a case must be made.

When Cain (Ka-yin in Hebrew) is born, Eve declares “I have acquired [or gained, kaniti] a man with the Lord” (Genesis 4:1). Thus he is called Cain as a reflection of his mother’s joy-filled exultation. His life begins with happiness and celebration and is immediately followed by the birth of a brother. The sibling is called Hevel (Abel) and, surprisingly, the name is not explained. The Genesis text simply declares the child to be Hevel and then states that the younger became a keeper of sheep while Cain, the elder, became a tiller of the soil (Genesis 4:2).

Why does the text not explain the name Hevel? Perhaps because it assumes that we know that Hevel means “breath” or “vapor” and often “vanity,” as in Jeremiah 2:5 and 2 Kings 17:15. Hevel is insubstantial: a puff of smoke, a meaningless and fleeting vapor. (Note its use in Isaiah 57:13 and Proverbs 21:6, and 36 times in Ecclesiastes). Surely it is not the kind of name a parent would want to give a child. And since almost all the proper names in Genesis are explained by assonances, and thus given a value, a possible conclusion might be that Hevel is less a name than it is a description. The second son of Eve, the text tells us, is not substantial: Like a puff of air, Hevel has neither vitality nor materiality. He is little more than a shadow on the stage. Indeed, Abel/Hevel says not one word in the entire story. It is not that he has a weak character—he has no character at all. Were it not for the fact that he is murdered, he would have no role whatsoever. In effect, we never have a chance to meet this second son—we are never really even introduced to him, because the focus of the story is on the first son, Cain.

Cain’s tragedy is described in only three verses: “After some time, Cain brought an offering to the Lord from the fruits of the ground; and Abel, he also brought from the choicest of the firstborn of his flock. The Lord gave attention to Abel and his offering; but to Cain and his offering He did not give attention; and Cain was very angry and his face fell” (Genesis 4:3–5).

Why is Cain so upset? Perhaps it is because God’s behavior was more than unfair, it was unjust. Cain had much more invested in his offering than his brother. As a farmer, Cain had to prepare the ground, secure and then plant his seeds, tend and take care of the field, harvesting its fruit at the right time. As a “tiller of the soil,” Cain devoted time and energy to the production of the fruit that 042he brought to the Lord. In bringing his gift, he was truly giving the Lord something of himself.

His brother, on the other hand, brought an offering of little personal sacrifice. Sheep feed themselves, take care of themselves and produce new sheep all by themselves. As a shepherd, the younger brother had only to keep watch. Even protecting his flock from wild animals would not have been a strenuous responsibility.

It is therefore easy to understand Cain’s anger when he saw that his brother’s offering was regarded while his was not. It was not fair, given all 043that he had personally done to produce his first- fruits and given how little his brother had done. Where was divine justice?

But the Lord did not ignore Cain altogether: “Why are you angry, why is your face fallen? Look, if you do well, there is uplifting; but if you do not do well, sin crouches at the door, and its urge is toward you—but you can control it” (Genesis 4:6–7). Much commentary has been written on these two verses, questioning the Hebrew grammar, the meaning of the words themselves and, of course, the intent of the message. The central issue is the statement to Cain “if you do well there is uplifting, but if you do not do well, sin crouches at the door.” The question is with what is Cain supposed to do well? Surely the nature of the offering is not what is referred to, for we are given no indication that his sacrifice was either insufficient or deficient. It must be that Cain is told that if he now “does well” with how he handles the Lord’s response to his offering, he will be lifted up, and if he does not, then sin will “get him.” Clearly he has not done anything wrong yet, the choice still is his: to do well or not.

Cain is being asked how he will respond to the pain of disregard, to divine indifference. If the world is not just, how is one to act in return? If one chooses well, there is “uplift”; that is, if one accepts that bad things do sometimes happen to good people not because the people are bad or good but just because they live in a natural world where accidents naturally occur, then uplift comes from the knowledge that the Lord is not indifferent or uncaring, only waiting to respond to the right questions.

And if one does not do well, a person will lash out at what he sees as an unjust world. The opportunity- to-sin waits, crouches, is coiled like a serpent outside the door of the person who is not able to control himself. Cain does not—chooses not to—master his pain and grief and becomes self- serving and self-righteous. He turns to his brother and speaks … but what? The words are missing from the Genesis text. Perhaps it is that Cain turns to his brother to complain, only to realize that Abel himself has nothing to do with the problem.

It is also worth pondering for a moment Cain’s intent as he struck his brother. While he certainly intended to hurt Abel, perhaps he was not aware that his action might kill him. Indeed, until Abel’s death, no one has ever died. Cain might have been completely surprised that his brother did not get up from the ground. He is therefore guilty of assault, but one wonders if he can rightly be called a murderer if he did not understand the ultimate consequences of his action.

If Cain does not do well with how the Lord responds to him, Job does. Like Cain, he lives according to the rules, only to discover that there are no rules. His friends and wife declare that the Lord blesses those who are good and curses those who are evil. Job has come to learn that this is not true, and he struggles to fit “right” theology into the reality of his world. He desperately wants to justify an all-powerful deity that can also be all-good. We follow Job, the tragic hero, to see how he will respond to the seeming indifference of an uncaring God.

The quality of Job that the text praises, his saving attribute, is his integrity. In his commentary on Job 2:9, J. Gerald Janzen understands the virtue of integrity as “indicating (a) the quality of individual wholeness (b) arising in and from one’s relation to God, and (c) expressing itself in … straightforward conduct.”b Here in the character of Job is the response the Lord had hoped for from Cain. Integrity is the human quality of “wholeness.” As a faith statement, integrity is the knowledge that the world does operate with natural laws of justice, as an integrated whole, according to an order determined by the Infinite Creator. The integrated order transcends any individual person. Fire, wind and earthquake are necessary elements of a living world. Illness, pain and even death are part of humanness. Because our universe is “alive,” its random nature cannot be bound by the rules of what we consider to be fair or just.

Like Cain, Job is upset when human righteousness does not prompt divine notice. But Job is different from Cain in his response: His integrity, his “wholeness” with the Lord transcends the passion of the moment. He is able to affirm God’s ultimate goodness, while acknowledging the random nature of his creation. Job comes to know that if he were to be treated with the justice that Cain and Job’s three friends expected, then the rules of our natural world would necessarily be suspended. If the world were to operate with universally fair and just laws, then it could not be a world of natural laws. God’s promise to Cain is realized through Job: “Look, if you do well, there is uplifting.” Job accepted the uncertainty of a living natural universe. He knew that his relationship with God would support him in whatever happened. He did well in spite of the pain and was uplifted in the end.

Ronald S. Hendel’s article, “When God Acts Immorally—Is the Bible a Good Book?” BR 07:03, obviously touched a raw nerve. In examining the story of Cain, Hendel suggested that God may not be a perfect God, but a good God nevertheless, and that the Bible may not be a wholly good book, but a “good enough” book. Judging from the outpouring of letters that followed, many readers took exception—even offense—at Hendel’s reading of the story.a Without going over the same ground as Hendel and the subsequent letter writers, it might be fruitful to review the story of Cain […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Readers Reply, BR 07:04 and Readers Reply, BR 07:05.