How the Ancients De-Loused Themselves

066

The lowly louse has been harassing humankind for millennia. In the past few years we have been trying to locate the little critter archaeologically. Not only has our search for the louse itself been successful, but we have in the process even discovered an effective ancient delousing procedure.

Ancient literature is full of references to this little plague. Indeed, the most famous reference to lice in antiquity is quite literally as a plague—the third plague visited on the Egyptians when pharaoh denied Moses’ request to let the Israelites go:

“[Pharaoh] became stubborn and would not heed them, as the Lord had spoken. Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘Say to Aaron: Hold out your rod and strike the dust of the earth, and it shall turn to lice throughout the land of Egypt.’ And they did so. Aaron held out his arm with the rod and struck the dust of the earth, and vermin came upon man and beast; all the dust of the earth turned to lice throughout the land of Egypt” (Exodus 8:15–17 [11–13 in Hebrew]).

Medical historians as well as Biblical scholars have long debated whether the Hebrew words (

In any event, hundreds of years before Moses and Aaron lived, an Egyptian text (known as Papyrus Ebers, 067from the 16th century B.C.) listed a remedy for the relief of lice (a potion of date flour drunk warm was spit where the lice were). Moreover, desiccated head lice and their eggs have occasionally been found attached to the hair of Egyptian mummies, and pubic lice have also been found in the genital area.

The Greek historian Herodotus (480–408 B.C.) tells us that Egyptian priests and scribes solved the problem of lice by shaving their bodies to prevent infestation.1

Actually lice have lived on the planet much longer than humans. According to entomologists, the common human head louse (Pediculus capitis) and body louse (Pediculus humanus) are morphologically very similar to the lice that infest chimpanzees and cebus monkeys today; and the human pubic louse (Phthirus pubis) is morphologically similar to the lice that infest chimpanzees and gorillas.2 This suggests that all these lice shared a common ancestor on the evolutionary timeline somewhere between four and eight million years ago, long before humans arrived on the earth.

Our interest in lice was aroused in 1986 when a cache of skeletons, possibly the remains of monks, from the sixth century A.D. was discovered in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea. Anthropologists had been examining hair samples from ancient human remains for decades. Here was our chance. Monks were especially attractive for this purpose because lice were often considered a sign of a saintly way of life. Pursuant to their ascetic philosophy, early Christian hermits and monks often regarded louse infestation as a sign of humility. Even the emperor Julian the Apostate (331–363 A.D.) boasted of his unkempt appearance and his shaggy beard with lice scampering through it as if the whole thing were a thicket of wild beasts. St. Francis of Assisi (1182[?]–1226 A.D.) is said to have called lice “pearls of poverty.”

069

Jewish and Moslem traditions also discuss the problem of lice, but from a slightly different perspective. Moslem tradition forbids killing lice in holy places, especially in mosques.3 The most serious discussion of lice in Jewish tradition concerns the laws of the sabbath; in the end it was decided that one could remove a louse on the sabbath, but not kill it.4

The first step we took in our search for lice among the skeletons was to examine carefully hair samples. Remnants of clothing were also examined for the presence of body lice. The results, however, were negative.

Our interest in lice having been aroused, we then decided to examine combs, a number of which had survived and been recovered in other excavations. The area near the Dead Sea is 1,200 feet below sea level and has an average annual rainfall of less than 3 inches. Organic material from this area is so well preserved that a layperson might think ancient combs recovered here were of modern origin.

The first two combs we examined were from Qumran, the settlement adjacent to the caves where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found. The site had been destroyed in 68 A.D. by Roman armies advancing on Jerusalem during the First Jewish Revolt against Rome. The combs were unearthed in the 1950s in an excavation directed by Père Roland de Vaux of the École Biblique in Jerusalem. These combs, made of wood, were in an excellent state of preservation.

We first placed the combs in a solution of 70 percent alcohol to free some of the organic and inorganic debris embedded between the teeth of the combs. Then we mechanically removed the rest with a needle. Next, the solution with the debris was filtered. Finally, we examined the filtrate microscopically.

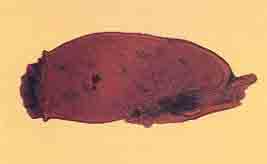

In the first comb we found the remains of ten head lice in all developmental stages and 27 louse eggs. Ten eggs were still unhatched and we could even see the embryos inside.

In the second comb we found 14 eggs, all hatched.

Buoyed by these finds, we collected combs from other excavations, first from caves where Jewish rebels held out during the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 A.D.), led by the legendary Bar-Kokhba, and then from other sites in the Jordan Valley and in the Negev desert as well, where similar ecological conditions preserve ancient remains.

We even examined some hair samples from Masada, Herod’s mountain fortress/palace where Jewish rebels in the First Jewish Revolt held out for three years before killing themselves when a Roman siege neared a successful conclusion.

This time we found seven eggs in the hair samples.

Our examination of debris from these combs also proved positive; thus far we have examined 24 combs. Eight out of 11 combs found in the Judean Desert contained head lice and/or louse eggs. One comb contained four lice and 88 eggs. In the combs from the Negev Desert, four out of 13 combs showed evidence of lice and/or louse eggs.

The high percentage of combs infested with lice and/or louse eggs indicates how widespread the problem was in ancient times, at least in isolated areas, where lack of hygiene and crowded living conditions would encourage parasitic infestations. The large number of lice and eggs collected from these combs also indicates how heavy the infestation was. Remember that the number of lice and eggs originally on the combs has been reduced over time, and also as a result of being buried and excavated. In addition, in many cases only fragments of the original combs were available; several combs had been handled and partially cleaned by museum curators, for photography or other studies.

But the lice and eggs from the combs also tell us something else: They were very effective de-lousing implements. This is especially demonstrated by the presence in some combs of newly laid (unhatched) eggs. These eggs are deposited by the female louse approximately 0.2 inch (0.5 cm) from the scalp. These eggs are particularly difficult to remove even with modern combs. That these ancient combs were able to remove these eggs shows how effective the combs were.

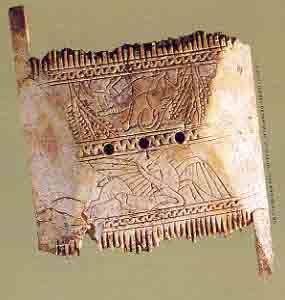

Actually, combs have not changed much over the ages. While hair combs are quite rare in prehistoric cultures, a few have been found in the Middle East as early as the Natufian period (12,000–10,000 B.C.), when man first began settling in permanent habitations. These early combs were fashioned from bone or ivory. Somewhat later, they were made of boxwood, native to Anatolia. In later periods, hair combs gradually became quite common.

Their design changed little, however. Modern combs are almost identical to those used thousands of years ago. If anything, combs found in archaeological excavations are artistically superior to, and at least as effective as, the ones we use today.

The majority of ancient combs are two-sided, one side with three to five teeth per centimeter (about 0.4 inch), and the other side with five to 15 teeth per centimeter.

We had assumed that combs were used almost exclusively for cosmetic purposes. Now it appears that they were also used as de-lousing implements. Indeed, the combs we examined appear to have been designed specifically for de-lousing. First the hair was straightened by combing it with the side of the comb that had the lower density of teeth; then the lice and eggs were removed with the opposite side of the comb, which had the greater density of teeth. That these combs could remove eggs deposited a mere half centimeter (about 0.2 inch) from the scalp reflects how efficaciously they were designed.

The lowly louse has been harassing humankind for millennia. In the past few years we have been trying to locate the little critter archaeologically. Not only has our search for the louse itself been successful, but we have in the process even discovered an effective ancient delousing procedure. Ancient literature is full of references to this little plague. Indeed, the most famous reference to lice in antiquity is quite literally as a plague—the third plague visited on the Egyptians when pharaoh denied Moses’ request to let the Israelites go: “[Pharaoh] became stubborn and would not heed them, as the […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username