042

When the first jewish revolt erupted in 66 C.E., Jerusalem was dominated by the Second Temple, which had been rebuilt by Herod the Great in the second half of the first century B.C.E. The thousands of pilgrims who flocked to the Temple included large numbers of Jews from outside the Roman province of Judea. Some of these pilgrims ultimately settled in Jerusalem and made it their home, others gained positions of status and authority, and many made the city their final resting place.

Both textual and archaeological evidence give vivid testimony to this diverse Diaspora community, including the individuals and families who immigrated, the places from which they came, and their impact on the city.

We know from historical and literary sources—including Josephus, the New Testament, and the Mishnah—that Diaspora Jews were well represented in Jerusalem by Herod’s time, thanks to his promotion of immigrants, particularly from Egypt and Babylonia, to positions of priestly authority. According to Josephus, Herod first appointed the Babylonian Hananel to the high priesthood (Antiquities 15.22), followed by the Egyptian Jeshua son of Phabi, who himself was then replaced by Simon son of Boethus, an Alexandrian Jew (Antiquities 15.322). Herod even took Simon’s Egyptian daughter, Mariamne, as his wife. From the Mishnah, we also learn that 043the famous first-century C.E. Jewish sage Hillel, who established an influential religious school in Jerusalem, emigrated from Babylonia (Sifre Deuteronomy 357).

The New Testament contains numerous references to Diaspora Jews living in Jerusalem, including well-known figures, such as Paul (Saul) of Tarsus; Simon of Cyrene (Mark 15:21; Luke 23:26); Barnabas (Joseph), “a Levite, a native of Cyprus” (Acts 4:36); and Nicolaus, a proselyte from Antioch (Acts 6:5). More broadly, however, the Book of Acts lists Jews from various foreign lands who were living in Jerusalem in the first century:

Now there were devout Jews from every nation under heaven living in Jerusalem … Parthians, Medes, Elamites, and residents 044of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabs.

(Acts 2:5-11)

It is against these textual sources that we can better understand and interpret the varied archaeological evidence for Jerusalem’s Diaspora Jewish communities, which includes monuments and rock-cut tombs, building and funerary inscriptions, and inscribed ossuaries.

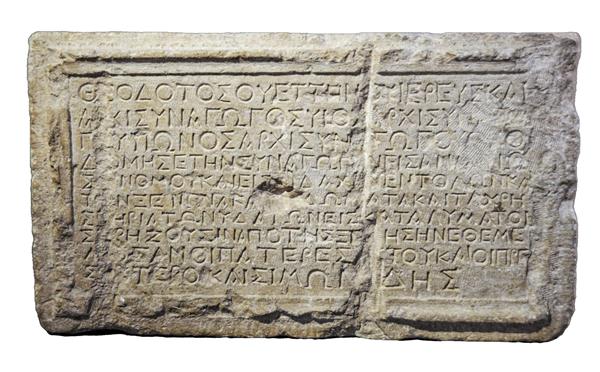

Among the more striking pieces of archaeological evidence for Jerusalem’s Diaspora Jewish community is a stone block inscribed in Greek that was found during early excavations in the City of David. The inscription, which was discovered in a dump along with other architectural fragments, commemorates a synagogue built by Theodotos son of Vettenos:

Theodotos son of Vettenos, priest and archisynagogos, son of an archisynagogos, grandson of an archisynagogos, built the synagogue for the reading of the law and teaching of the commandments, and the guesthouse and the (other) rooms and water installations(?) for the lodging of those who are in need of it from abroad, which (= the synagogue) his forefathers, the elders and Simonides founded.

Presumably, the building associated with the inscription was located nearby and was destroyed in 70 C.E. Although Theodotos is a common Greek name, Vettenos is thought to be Latin, suggesting he was from an immigrant family, perhaps originally from Rome or the Italian peninsula. The fact that Theodotos was a 045priest and a third generation archisynagogos (a Greek title meaning “head of the synagogue”) and had the means to dedicate a synagogue indicates this was an elite family. While it remains unclear if Theodotos’s synagogue served an exclusively immigrant or Diaspora congregation, like the “synagogue of the Freedmen” mentioned in Acts 6:9, the inscription clearly indicates the wide-spread presence of foreign, Greek-speaking Jews in Jerusalem during the first century.

The royal house of Adiabene (a small kingdom located on the upper Tigris River in northern Mesopotamia) was perhaps the most illustrious Diaspora Jewish family in first-century C.E. Jerusalem. Helena, the queen of Adiabene, was a convert to Judaism. Following the death of her husband Monobazus in about 30 C.E., she along with several other members of the royal family moved to Jerusalem, while her son Izates, also a Jewish convert, succeeded to the throne of Adiabene. Helena was a generous benefactress who provided the people of Jerusalem with food during a famine (Josephus, Antiquities 20.51–53), and she is also commemorated in the Mishnah for her donations to the Temple, which included a golden candelabra that hung above the Temple’s doorway (m. Yoma 3:10).

According to Josephus, Helena’s palace was in the vicinity of the Akra, a second-century B.C.E. Seleucid fortress built just south of the Temple Mount (War 6.355). Since 2007, excavations in 046the Givati Parking Lot at the northwest end of the City of David have brought to light the basement rooms of a monumental building dating to the late Second Temple period, which some propose is Helena’s palace.a The massive walls are built of huge fieldstones, some weighing several hundred pounds. Fragments of colorful frescoes found in the collapse indicate that the upper stories were richly decorated, while pieces of columns belonging to the building were incorporated into a later structure above.

Helena returned to Adiabene soon after Izates’s death. When she died soon thereafter (c. 60 C.E.), her son and Adiabene’s new king, Monobazus, “sent her bones and those of his brother to Jerusalem with instructions that they should be buried in the three pyramids that his mother had erected at a distance of three furlongs from the city of Jerusalem” (Antiquities 20.95). Josephus mentions that the tomb of Helena was located outside Jerusalem’s Third Wall, the city’s northernmost line of fortification during the first century C.E.

In 1863, a French explorer named Louis Félicien de Saulcy began excavations at the tomb of Helena, which he believed was the tomb of the kings of ancient Judah.b The tomb is a huge complex with an enormous courtyard hewn out of bedrock accessed via a monumental rock-cut staircase. The burial chambers are located on the courtyard’s west side, with a porch that originally had two columns, a decorated architrave, a 047Greek-style Doric frieze, and three monumental pyramidal markers above. The tomb’s interior chambers contained 50 burial niches, and the innermost room, which is aligned with the center of the porch façade, may have contained the burial of Queen Helena. The names Sada and Sadan, both meaning “the Queen,” were inscribed in Aramaic on one of the sarcophagi found by de Saulcy, who reported that a woman’s skeleton dressed in a garment adorned with gold disintegrated when the sarcophagus was opened.

Another prominent Diaspora Jew in first-century C.E. Jerusalem was Nicanor of Alexandria, who donated a set of bronze gates to the Temple. Unlike the other gates of the Temple, Nicanor’s were left ungilded to commemorate a miracle that reportedly occurred while they were being transported by sea from Alexandria. According to the story, while navigating through a storm, sailors threw one of the gates overboard to lighten the ship’s load, though Nicanor held fast to the other, refusing to jettison it into the sea. The storm then ceased immediately, and when the ship reached port at Akko, the first gate miraculously resurfaced (t. Kippurim [Yoma] 2:4).

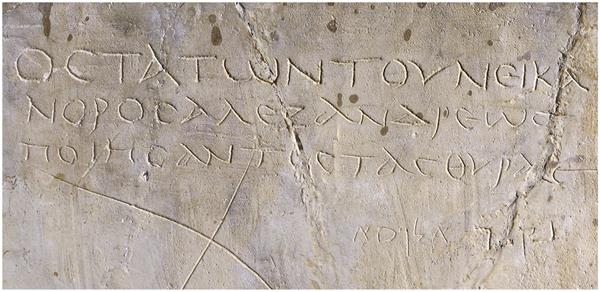

In 1902, an extensive tomb complex, which features a pillared entry porch and five interior burial halls with numerous burial niches (loculi), was discovered on Mt. Scopus. The elaborate tomb was well designed and expertly carved.1 One of the seven ossuaries found in the tomb bears a Greek inscription, “The ossuary of Nicanor of Alexandria, who made the gates,” followed by the Aramaic inscription “Nicanor the Alexandrian.”

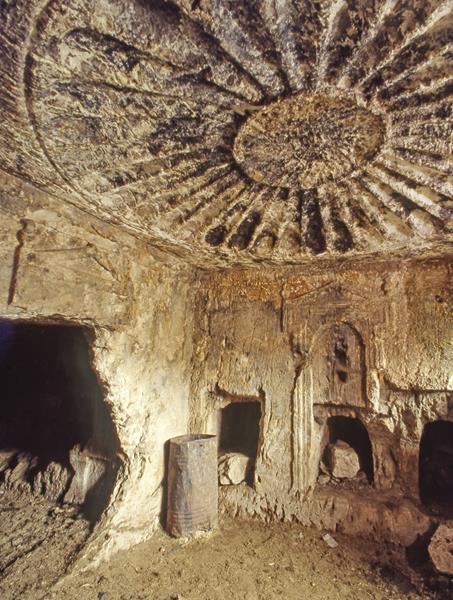

The so-called Akeldama tombs—three burial caves on the western slope of the Kidron Valley—have also provided abundant archaeological and epigraphic evidence for prominent Diaspora Jewish families in late Second Temple Jerusalem.2 Each of the caves contains three to 048049four chambers with several burial niches and recesses for interred remains. The most elaborate of the tombs—known as the Ariston Family Tomb after the names inscribed on the ossuaries found inside—features a burial chamber adorned by a recessed frame topped by an arch, and a pivoting, paneled stone door that could be closed and locked. The chamber was decorated with incised geometric panels painted in red and architectural elements carved in low relief. The unique decorative features of the Akeldama tombs and the high quality of workmanship suggests they belonged to some of Jerusalem’s most affluent Jewish families. But were these Jewish families local to Jerusalem, or did they originally come from elsewhere?

Forty ossuaries and one sarcophagus were found in the three burial caves, some decorated and some inscribed, mostly in Greek. The names in the inscriptions suggest that the families buried in the three caves were related and came from Apamea and Selucia in Syria. These include three ossuaries inscribed in Greek and Aramaic with the names of Ariston and his two daughters, Shelamzion and Shalom. Ariston’s ossuary is also inscribed in Aramaic “Yehuda the proselyte,” indicating that at least one convert—possibly Ariston himself—was buried in the tomb. Intriguingly, this Ariston could be the same person who is mentioned in the Mishnah as bringing firstfruits to the Temple: “Ariston brought his firstfruits from Apamea and they accepted them from him, for they said: He that owns [land] in Syria is as one that owns [land] in the outskirts of Jerusalem” (m. Hallah 4:11).

Another burial cave associated with Diaspora Jews was discovered in the early 20th century just north of Jerusalem near Nahal Atarot. The single-chamber burial cave with loculi on two levels contained more than 30 ossuaries, the majority of which are inscribed. Sixteen are in Greek, five are in Aramaic, and four are in Palmyrene. The names are Jewish, Greek, Latin, and Palmyrene, among others. One individual was a priest named Shamaya. Three places are mentioned in the inscriptions: Chalcis, Alexandria, and Seitos. The place names and Palmyrene inscriptions point to a north Syrian origin for the family or families interred in the tomb, while a wall inscription, which is painted in Greek above one of the loculi, states that the niche held “the bones of those who emigrated” to settle in Jerusalem.3

We can see, therefore, that tombs associated with Diaspora Jews are dispersed throughout Jerusalem. Some of them belonged to immigrant families, while others contained the remains of individuals who apparently married into local families. The tombs of Helena and Nicanor and the Akeldama tombs are among the largest and most conspicuous in Jerusalem’s funerary landscape, suggesting that their owners sought to make a statement about their standing within local Jewish society.

We should remember, however, that almost all the available written and archaeological evidence relates to Diaspora Jews who were part of Jerusalem’s wealthy elite. Lower-class Diaspora Jews, though largely invisible in the literary and archaeological records, must also have been present in Jerusalem. One piece of evidence is a list of payments to workers inscribed in Hebrew on an ossuary lid from the Mt. of Olives, which includes two Galileans and a Babylonian.4 This inscription shows that immigrants were represented among different socioeconomic groups within the city.

Clearly, late Second Temple period Jerusalem was a cosmopolitan city filled with Jewish pilgrims and immigrants from abroad. These Diaspora Jews supported and participated in the Temple cult and were integrated into various aspects of everyday life in Jerusalem, including adopting the local burial customs. At the same time, many maintained ties to their homelands, native languages, and customs through membership in immigrant synagogue congregations. Not surprisingly, it was the wealthiest and most prominent immigrants, such as Queen Helena, who had the greatest impact on the city’s landscape and on the lives of its residents.

Jerusalem was home to numerous Diaspora Jewish communities before the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E. From texts to tombs, evidence of these communities abounds. See what it reveals about the city’s cultural, economic, and religious life and diversity.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1. R. Steven Notley and Jeffrey P. García, “Queen Helena’s Jerusalem Palace—In a Parking Lot?” BAR, May/June 2014.

2. See Andrew Lawler, “Who Built the Tomb of the Kings?” BAR, Winter 2021.

Endnotes

1.

Amos Kloner and Boaz Zissu, The Necropolis of Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period (Leuven: Peeters, 2007), p. 179.

2.

See Gideon Avni and Zvi Greenhut, The Akeldama Tombs, Three Burial Caves in the Kidron Valley, Jerusalem, IAA Reports 1 (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 1996).